Spinal Surgery: Observing a Five-Hour Procedure

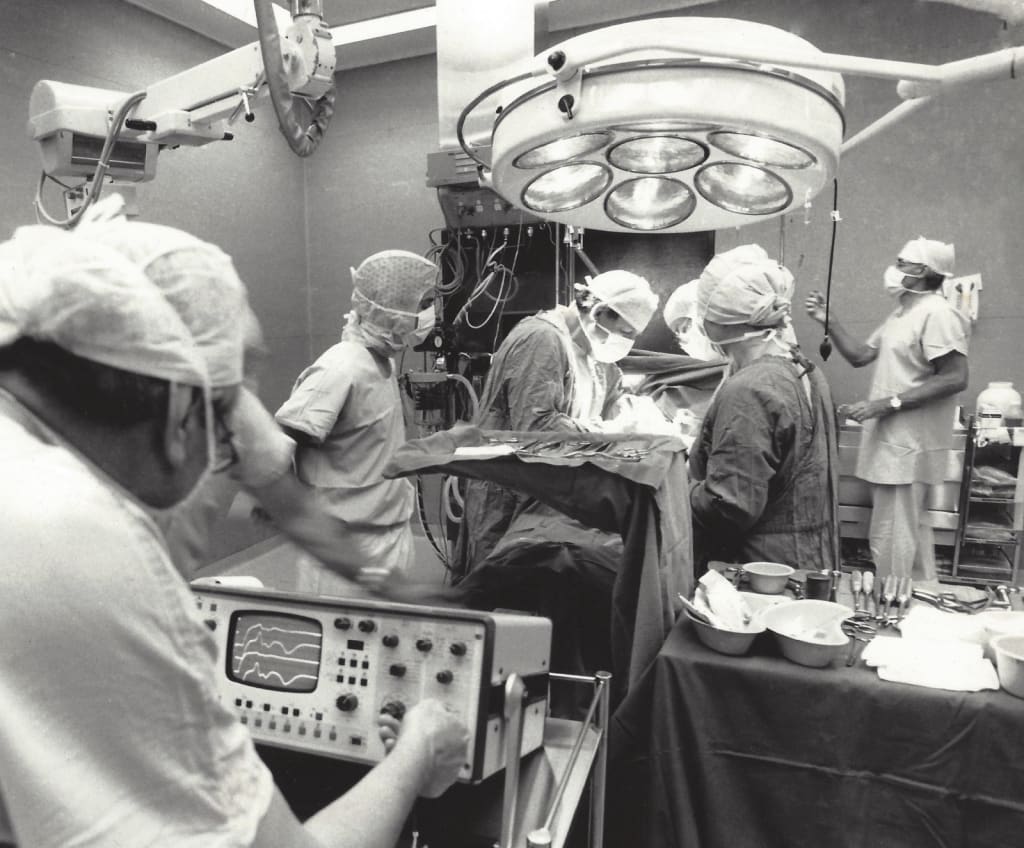

Donning scrubs to observe an operation to correct spinal deformity is a fascinating experience – but not one for the faint hearted.

“YOU’VE NEVER SEEN an operation before?” asked Dr Chris Pike as we entered Theatre One at the Prince of Wales Children’s Hospital in Sydney, Australia. “Well, you’ve picked just about the most gruesome one for starters.”

I’d come to observe spinal correction surgery for my newspaper, The Sydney Morning Herald. Having washed up thoroughly under the supervision of a nurse, I was now decked out in surgical scrubs: a short-sleeve shirt, loose-fitting, drawstring pants, disposable overshoes, a surgical cap and face mask, plus my notepad and pen. No gloves were needed as I’d be hovering near the operating table, but not touching anything.

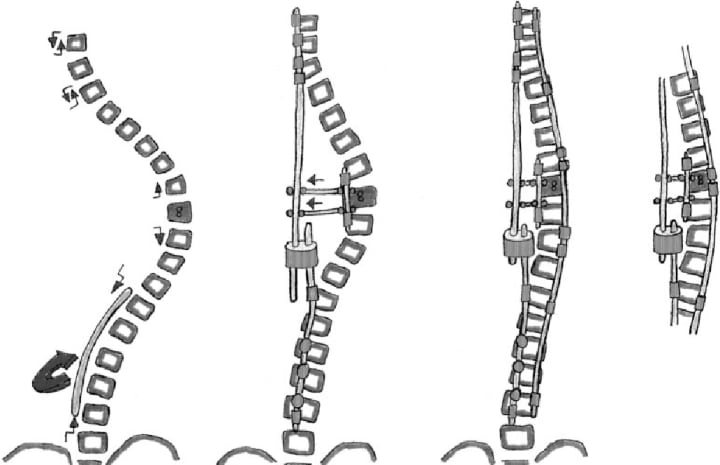

Pike — who insisted I not use his real name — was going to perform one of the dozens of Cotrel-Dubousset operations that take place around the world every year, the most effective surgical procedure for spinal deformities. He’d travelled to France to learn the method, in which tiny metal braces and long steel rods are attached to a patient’s vertebral column, and the spine then straightened by rotating the rods upright.

In the theatre, a 13-year-old girl lay face down on the table, anaesthetised, naked and raised in the mid-section by a cushioned bench. She suffered from adolescent idiopathic scoliosis, or AIS, a spinal deformity brought on at puberty and affecting about one in 1,000 adolescent girls. ‘Idiopathic’ indicates the condition has no identifiable cause, although almost a third AIS patients have some family history of scoliosis.

A metal crown was riveted to the patient’s skull, and a set of weights attached which tugged on the headpiece, partially straightening her otherwise crooked spine. Green cloth was draped over everything but her back, the cloth stitched into her skin so as not to slip off. An antiseptic was painted on by a nurse, and a straight line drawn with a marker down the middle of her back.

Pike began with a 15 cm incision into the girl’s right hip, reaching deep into the bone. Scissor-like grapplers were attached to the skin and held the incision open some 7 cm. With a chisel-like instrument and a stainless-steel hammer, Pike began to chip away at bone.

The sound was both familiar, and startling: like using an axe to hack into a leg of ham — except this was human bone. The anaesthetised patient shook with each forceful application of the hammer. The scrub nurse held out a small bowl into which Pike dropped pieces of chipped bone. “That’s for the bone graft,” he told me. “She’s going to need that later.”

It was during this harrowing but early phase of the surgery that my previously blasé colleague, a photographer — who’d heartily mocked my earlier uncertainty about watching a five-hour operation— blanched. Within minutes, he announced to the operating theatre that he’d obtained sufficient photos and needed to take his leave.

Pike proceeded to cut a 35 cm incision down the girl’s back. Using an electrically heated scalpel, he continued to cut deeper and deeper into the flesh. Four larger versions of the scissor-like grapplers came out to hold back the flesh. The heated scalpel cauterised ruptured blood vessels as it cut, reducing the flow of blood. The registrar, holding a mechanical sucker, worked around the lead surgeon, sucking blood away where it began to pool.

Pike occasionally hummed to the Muzak coming from overhead. “You know what that song is, anybody?” he asked as his gloved hands worked inside the girl’s back. “That’s ‘True Love’, a song from a movie called High Society, with Bing Crosby and Grace Kelly.”

Soon, a large section of flesh was peeled back and the girl’s spine, twisted up into her right shoulder, was visible in its entirety. It was a mass of spongy red, white and mustard. Pike chipped more bone away deeper into sections of the vertebrae, then inserted stainless steel hook-clips up and down the spine. There were eight in all. He occasionally peered at single foolscap sheet of paper pinned to the green cloth, on which a hand-drawn diagram of the girl’s crooked spine indicated where the hooks were meant to be inserted. The yellow sheet was sprayed almost white with steriliser.

“I remember a registrar I had working with me, who I used to have competitions with [over] who could pick the greatest number of tunes,” he said of the Muzak. “I beat him hands down, but over the months he started getting better. He got so good, he could pick a tune before it had started properly. I used to dread Friday mornings.”

Pike looked down to the foot of the surgical bed, where clinical physiologists were monitoring signals sent up and down her spine, checking for any breach of the spinal canal, a cavity that runs through each vertebra and encloses the spinal cord. They signalled all was well.

“So we agreed to a showdown one Friday. The week before, I rang the matron to ask for a list of next Friday’s Muzak. She said she didn’t know where to get them, but said that [the registrar] would know, ’cause he’s had the advance list for months.”

The hook-clips in place, Pike called for the bowl with the patient’s bone fragments he’d earlier chipped from her hip. He covered the remaining spaces around the inserted hooks with the fragments, sealing it into the vertebrae sections. Using a two-handed tool, he carefully bent a 20 cm metal rod into a shape that matched the now only-slightly irregular line of the patient’s spine. After a few tries, the two aligned, and he inserted the rod through the hooks, using a large pair of pliers with a screw-grip holder.

“If I tried to buy this from a surgical supplier,” Pike said, motioning to the pliers, “it would have cost me $600. I got the same sort of thing from BBC Hardware for $60.” The first rod was inserted through the hooks, holding the girl’s spine rigid. Screws were then driven through the hook-clips and into the rod. “Now for the moment of truth,” he said.

With the help of his assisting registrar, Pike grabbed the rod with two pliers and, ever so slowly, rotated her spine about 50 degrees back to the left, straightening it. Another, much straighter rod was then inserted into the four other hooks alongside, and two bridging clips screwed into place to lock the rods together.

Bits of excess stainless-steel rod were bolt-cut away, and more screws riveted into the dual assembly. The screw heads were then broken off. The rods were now irreversibly embedded in the girl’s back.

“She’ll be up in four days and back to school in three or four weeks,” said Pike, as he left the closing-up to junior surgeons. “It’s an amazing procedure. Before this, they had to wear a plaster vest for three months, and a plastic vest for another three months after that. With this, in six months, she can play tennis.”

The next morning, he visited his recovering patient in the children’s ward. The girl lay on her back, and was happy to see him. At Pike’s request, she twitched her toes and gently lifted her knees. Her spine was doing well, he pronounced.

“You are Doctor [Pike]?” asked an elderly woman, the girl’s grandmother, in a thick accent, her eyes moist and her voice halting. “You are a good man, a very good man, doctor. Thank you.”

He turned to me, partly embarrassed by the emotion and sincerity of the woman, partly afraid how this might play in the article. “Don’t quote that.”

Like this story? Please click the ♥︎ below, or send me a tip. And thanks 😊

About the Creator

Wilson da Silva

Wilson da Silva is a science journalist in Sydney | www.wilsondasilva.com | https://bit.ly/3kIF1SO

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.