ascular Compression Misconceptions (part 2/4)

Separating Fact from Fiction

Welcome back to the second post on misconceptions about vascular diseases. In case you missed our first post, you can read it here. In this second post, we will be addressing some other misconceptions that people often have about the symptoms and treatment options for vascular compression diseases (VCDs). So, let's dive in and learn more about these myths.

Misconception #6: Vascular compressions diseases always cause visible swelling

Fact: While some VCDs can result in visible swelling or edema, not all cases will present with this symptom. The clinical manifestations of vascular compression diseases can vary widely, depending on the specific condition, the severity of the compression, and the structures involved (e.g., arteries, veins, or nerves). It is important not to rely solely on visible swelling as an indicator of vascular compression and to consider other symptoms and signs when evaluating a patient.

There are a few reasons why VCDs may present without significant swelling:

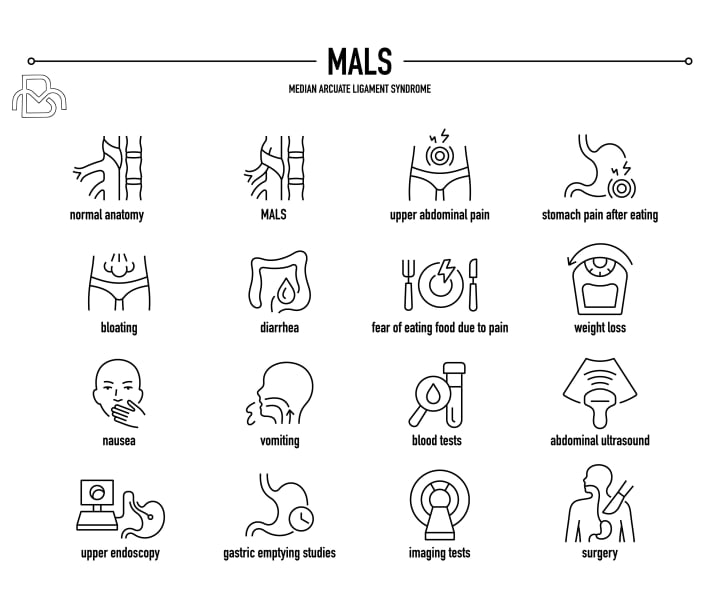

•Arterial compressions - Impingement or entrapment of arteries restricts blood flow to distal areas, but this typically does not cause fluid buildup since the volume of arterial blood is limited. Symptoms instead result from ischemia and may include pain, numbness, weakness and changes in temperature or color. Visible swelling tends to be minimal. Examples include thoracic outlet syndrome involving the subclavian artery and median arcuate ligament syndrome compressing the celiac artery.

•Acute venous compressions - Obstruction of veins in early or active stages does not always immediately produce swelling. It can take time for pressure to build up, blood to pool and fluid to accumulate in distal tissues. Swelling may emerge over hours to days, so lack of edema does not rule out an acute venous compression like Paget-Schroetter syndrome. Doppler ultrasound and venography are often needed to confirm the diagnosis.

•Nerve compressions - Impingement or entrapment of peripheral nerves themselves produces symptoms of pain, numbness, tingling and muscle weakness but typically results in little or no swelling. While nearby vessels may also be involved, the primary compression is of neural structures. Examples include classic and neurogenic thoracic outlet syndrome as well as ulnar tunnel syndrome. Visible edema is usually minimal.

•Inflammatory conditions - Disorders associated with chronic inflammation such as thoracic outlet syndrome and median arcuate ligament syndrome often flare and remit, with swelling only becoming prominent during acute exacerbations of symptoms. During dormant periods, visible edema may be absent even though symptoms persist to some degree and the anatomical compression remains. The amount of swelling present depends on the level of acute inflammation.

•Central sensitization - Prolonged symptom duration or severity of any compression syndrome can lead to changes in the central nervous system that cause persistent pain even once the initial swelling, anatomical issue or acute inflammation has resolved. Lack of visible edema does not indicate the pain and dysfunction are not real or due to a compressive condition. The nervous system itself has become the source of ongoing symptoms.

So the absence of substantial or visible swelling does not preclude the possibility of an underlying VCD. Arterial compressions, acute venous obstruction, nerve impingements, inflammatory conditions and central sensitization may all contribute to compression symptoms with limited edema formation. Careful evaluation including imaging and diagnostic tests guided by clinical findings will determine if there are signs of impaired circulation or neurological dysfunction to support a compressive syndrome diagnosis when swelling alone is lacking.

Misconception #7: Vascular compressions diseases only affect older adults

Fact: VCDs can affect individuals of any age, from infants to older adults. While some conditions may be more prevalent in certain age groups due to age-related changes in anatomy or risk factors, there is no age limit for the development of vascular compression syndromes. These conditions can result from congenital abnormalities, injuries, or other factors that are not exclusive to older individuals.

There are several reasons why VCDs may affect younger patients:

•Congenital anomalies - Some individuals are born with an anatomical predisposition to developing compressions, such as cervical ribs, a narrowed thoracic outlet or strangulated veins. Though present from birth, symptoms may not become apparent until later in life with injury, activity changes or weight gain.

•Nerve hypersensitivity - Younger patients with "irritable nerves" may experience compression symptoms even with mild degrees of anatomical narrowing or impingement. Their lower threshold for developing neurogenic pain and inflammation leads to earlier onset of symptoms.

•Repetitive arm motions - Occupations, hobbies or habits requiring frequent overhead arm positions or movements, such as in athletes, laborers and those who engage in repetitive computer/controller use, put younger individuals at higher risk for neurogenic and circulatory compression in the shoulders and arms.

•Postural or muscle imbalances - Poor posture, pectoralis minor tightness or weak mid-back muscles are more common in younger, active populations. These postural dysfunctions can directly create or contribute to compression syndromes involving the brachial plexus and subclavian vessels. Addressing flexibility and strength imbalances tends to provide the most benefit in younger patients.

•Trauma or injury - Acute injuries like clavicle fractures, first rib fractures or whiplash injuries usually occur in the earlier decades of life and may lead to post-traumatic compressions, especially if healing does not proceed properly. The trauma itself or subsequent inflammation can narrow passages, entrap nerves or limit muscle function resulting in pain and disability.

So while age-related degeneration can play a role in some vascular compression disorders, symptoms of impingement and entrapment may arise at any point in life, including in otherwise young, healthy individuals. A variety of factors unique to younger populations, ranging from congenital predisposition and trauma to poor posture and repetitive overuse, may contribute to or directly cause compressive issues in early life.

Younger patients with signs and symptoms possibly due to a VCD should be evaluated thoroughly rather than prematurely dismissed as too young to have a compressive disorder. Earlier diagnosis and management of nerve/vein entrapment in this group provides the best chance of quick recovery and avoidance of long-term complications from an often correctable problem.

Misconception #8: Vascular compressions diseases only affect the arms and legs

Fact: While many VCDs do involve the blood vessels and nerves in the arms and legs, these conditions can also affect other parts of the body. VCDs can occur wherever blood vessels or nerves are compressed by surrounding structures, such as bones, muscles, or other tissues. Understanding the diverse range of VCDs is essential for accurate diagnosis and effective treatment.

Some examples of compression syndromes affecting other areas include:

Abdominal vasculature compression - The celiac artery and mesenteric arteries can become compressed by the median arcuate ligament, often causing abdominal pain and nausea after eating. Compression of the left renal vein in the abdominal cavity may lead to pelvic venous congestion syndrome resulting in chronic pelvic pain.

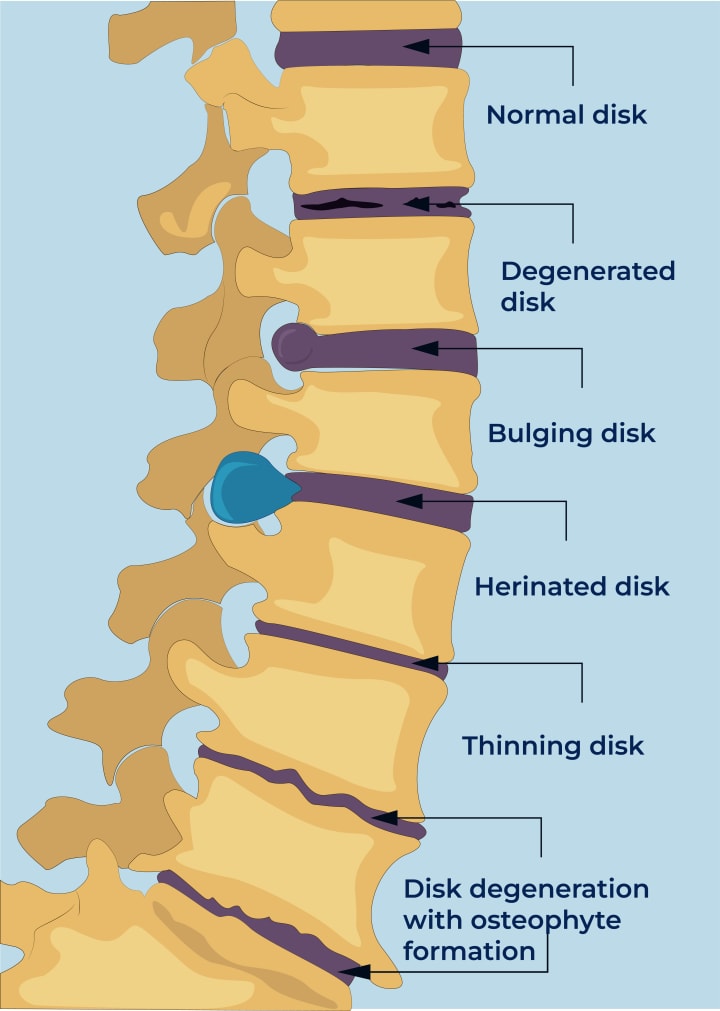

Lumbar spine compression - Degenerative changes and poor posture can compress lumbar arteries and veins in the lower back, contributing to low back pain and impaired circulation to the spinal cord. Nerve roots exiting the lumbar spine may also become compressed, causing sciatica and weakness.

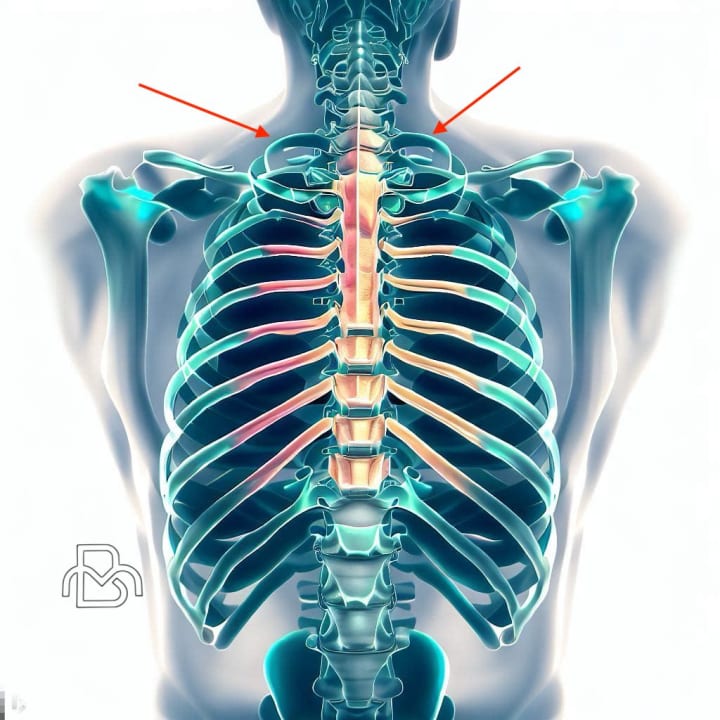

Thoracic spine compression - Arterial, venous or neural compressions in the mid-back may manifest as chest pain, shortness of breath or rib discomfort. Spinal cord compressions at this level may also cause changes in upper extremity sensation, pain or motor function.

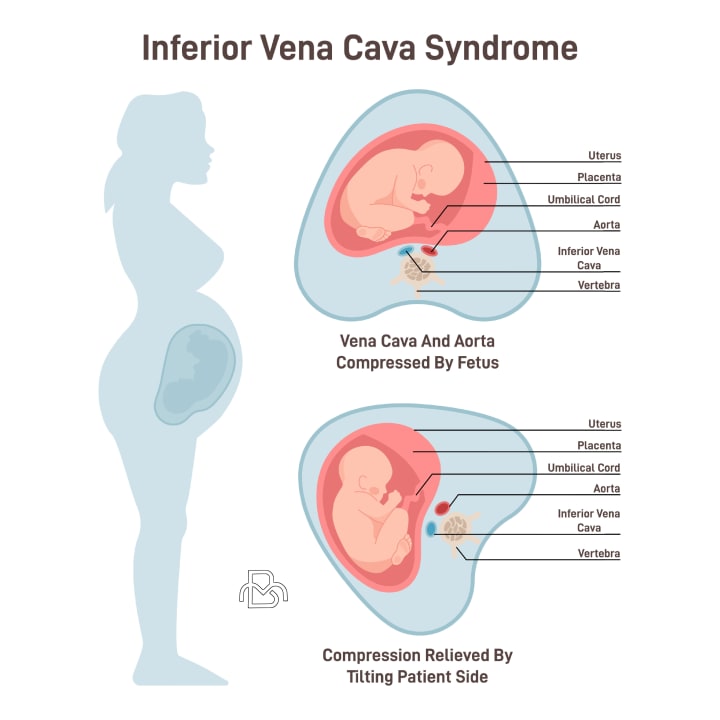

Venous compression in pregnancy - As the uterus enlarges during pregnancy, the inferior vena cava and pelvic veins can become obstructed, leading to lower extremity swelling, varicose veins, leg pain and risk of blood clots. Compression is more likely in women with a narrowed vena cava.

Intracranial compressions - Degenerative changes within the skull and upper cervical spine may compress cranial nerves, arteries and veins, as well as the spinal cord. This can produce symptoms like headaches, visual changes, pulsatile tinnitus, face pain and upper neck discomfort.

So compressive disorders are not limited to the arms, shoulders and legs. Vascular and neurogenic compressions can occur in many areas within the torso, spine and skull as well. Physicians should maintain a broad differential when evaluating patients with unexplained pain or other symptoms that could indicate impaired circulation or neural compression. Though less commonly considered, vascular compression syndromes in the abdomen, chest, neck and spine may be underdiagnosed and warrant further study.

These examples highlight the importance of recognizing that VCDs can affect various regions of the body, not just the arms and legs.

Misconception #9: If there are no visible symptoms, nothing needs to be done

Fact: While visible symptoms can provide important clues to the presence of a VCD, it is essential to recognize that not all cases will present with easily observable manifestations. In some instances, individuals with these conditions may experience non-visible or subtle symptoms that still warrant medical evaluation and intervention. Ignoring or downplaying non-visible symptoms can lead to delayed diagnosis, increased risk of complications, and reduced quality of life.

Some reasons why VCDs may warrant treatment despite limited external signs include:

Impaired circulation - Stenosis or obstruction reducing blood flow through an artery may not produce visible changes for months to years as collateral vessels compensate. But the compromised circulation stresses tissues by limiting oxygenation and nutrients, risking ischemia if flow is further reduced. Examples include celiac axis compression and mesenteric artery stenosis. Intervention aims to restore adequate circulation prior to threats to organ function or viability.

Nerve dysfunction - Gradual nerve compression or entrapment often emerges silently with little to observe externally. Yet axonal injury and impaired signaling may be actively progressing, with muscle atrophy and weakness eventually following. Reversing nerve dysfunction at an early stage requires addressing any anatomical impairment regardless of obvious signs. Examples include ulnar tunnel syndrome and lumbar spinal stenosis.

Postural strain - Poor posture, muscle tightness and inflexibility place abnormal stress and tension on areas like the thoracic outlet and celiac plexus over time without significant symptoms, but which may contribute to or provoke compressions later on. Correcting these subtle strains through postural training and targeted exercise helps support and stabilize vulnerable regions before more pronounced complications arise.

Venous hypertension - Blockage of veins leads to elevated venous pressure and blood pooling which causes gradual tissue changes and damage clinically. Skin signs may take months to become evident. Restoring venous return prevents long term effects of chronic venous congestion such as pain, swelling, varicosities and in severe cases tissue breakdown. Examples include May-Thurner syndrome and iliac vein obstruction.

Psychological impact - Prolonged anxiety, stress and reduced quality of life may arise in those aware of an underlying anatomical issue or tendency toward compression but with limited current symptoms or disability. Concerns over uncertainty of progression and long term outlook commonly produce varying degrees of distress and life limitation. Counseling and reassurance in these cases helps minimize psychological consequences, with treatment of any disorders themselves if significant deterioration occurs.

So absence of pronounced symptoms or visible signs alone should not be interpreted as evidence that all is well or that interventions would be unwarranted for certain vascular compressive conditions. Impaired function and progressive damage may actively continue behind the scenes, detectable only through specific clinical evaluations and tests until an advanced stage. Close monitoring of disorders prone to emerge subtly or insidiously, along with proactive steps to stabilize, support or modify contributing factors when possible, helps limit morbidity regardless of obvious external manifestations at a given point in time.

Early recognition and action directed at the underlying factors responsible for or strongly associated with the eventual emergence and progression of symptoms leads to the best opportunity for safe, effective and minimally disruptive management of many vascular compression syndromes prone to initially subtle development. Hesitation based primarily on absence of pronounced symptoms too often allows for advancement beyond a point of ready correction or containment through conservative means, necessitating more aggressive efforts to counteract effects set in motion much earlier but unaddressed. Where watchful waiting applies, it requires close collaboration and understanding of indicators that herald a pivot to action having become warranted and prudent before disability demands rather than suggests.

It is crucial for individuals experiencing any concerning symptoms, whether visible or not, to consult with a healthcare provider for a thorough evaluation. A detailed history, physical examination, and appropriate diagnostic tests can help identify the underlying cause of the symptoms and guide the development of a personalized treatment plan.

In some cases, even if the symptoms are mild or not visible, early intervention can help prevent complications and improve long-term outcomes. Patients and healthcare providers should work together to monitor and manage VCDs, regardless of the visibility of symptoms.

Misconception #10: Symptoms will not worsen over time

Fact: The progression of symptoms in VCDs can be variable, with some individuals experiencing stable symptoms, while others may notice a worsening of their condition over time. Factors such as the underlying cause, the severity of the compression, and the individual's overall health can all influence the course of the disease. It is important not to assume that symptoms will remain static and to monitor and manage these conditions appropriately to prevent complications and optimize long-term outcomes.

Some reasons why vascular compression symptoms typically worsen over time include:

Loss of nerve/muscle function - Prolonged compression of nerve axons and muscle ultimately results in cell death and tissue damage that does not readily heal or recover without intervention. Muscle atrophy, sensory loss and motor deficits emerge which, left unaddressed, may become permanent. Reversing these effects requires early decompression before severity has fully developed. Examples include severe carpal tunnel syndrome and lumbar radiculopathy.

Inflammation and scarring - Repetitive irritation of vessels and nerves triggers an inflammatory response that leads to fluid accumulation, adhesive scar formation and neural sensitization. Inflammation causes swelling and pain which may temporarily improve with rest only to flare again, while scarring permanently limits mobility and circulation. Anti-inflammatory treatment and minimizing re-injury are key before tissue changes become fixed. Examples include neurogenic thoracic outlet syndrome and ulnar tunnel syndrome.

Loss of compensation - The body's inborn mechanisms for adapting to and accommodating circulatory or postural changes have maximum capacity beyond which symptoms emerge and worsen. Arterial collateral branches, venous collaterals and musculoskeletal flexibility are gradually taxed until overwhelmed, allowing impaired function and disability to become evident. Intervention at this stage attempts to restore normal dynamics, but some level of permanent effects often remains.

So, without treatment to directly address the underlying anatomical or physiological impairment contributing in each case, symptoms arising from most any vascular compression disorder can be expected to advance in both severity and scope over months to years for the majority. Progression may be gradual or in acute exacerbations and remissions depending on cause and location, but continued decline is the natural course if left unmanaged based on current effects combined with potentials yet to emerge.

Early diagnosis, appropriate treatment, and ongoing management are crucial for preventing the worsening of symptoms and reducing the risk of complications in individuals with VCDs. Patients should work closely with their healthcare providers to monitor their symptoms and adjust their treatment plans as needed to maintain optimal long-term outcomes.

About the Creator

Mohammad Barbati

Mohammad E. Barbati, MD, FEBVS, is a consultant vascular and endovascular surgeon at University Hospital RWTH Aachen. To date, he has authored several scientific publications and books regarding vascular and venous diseases.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.