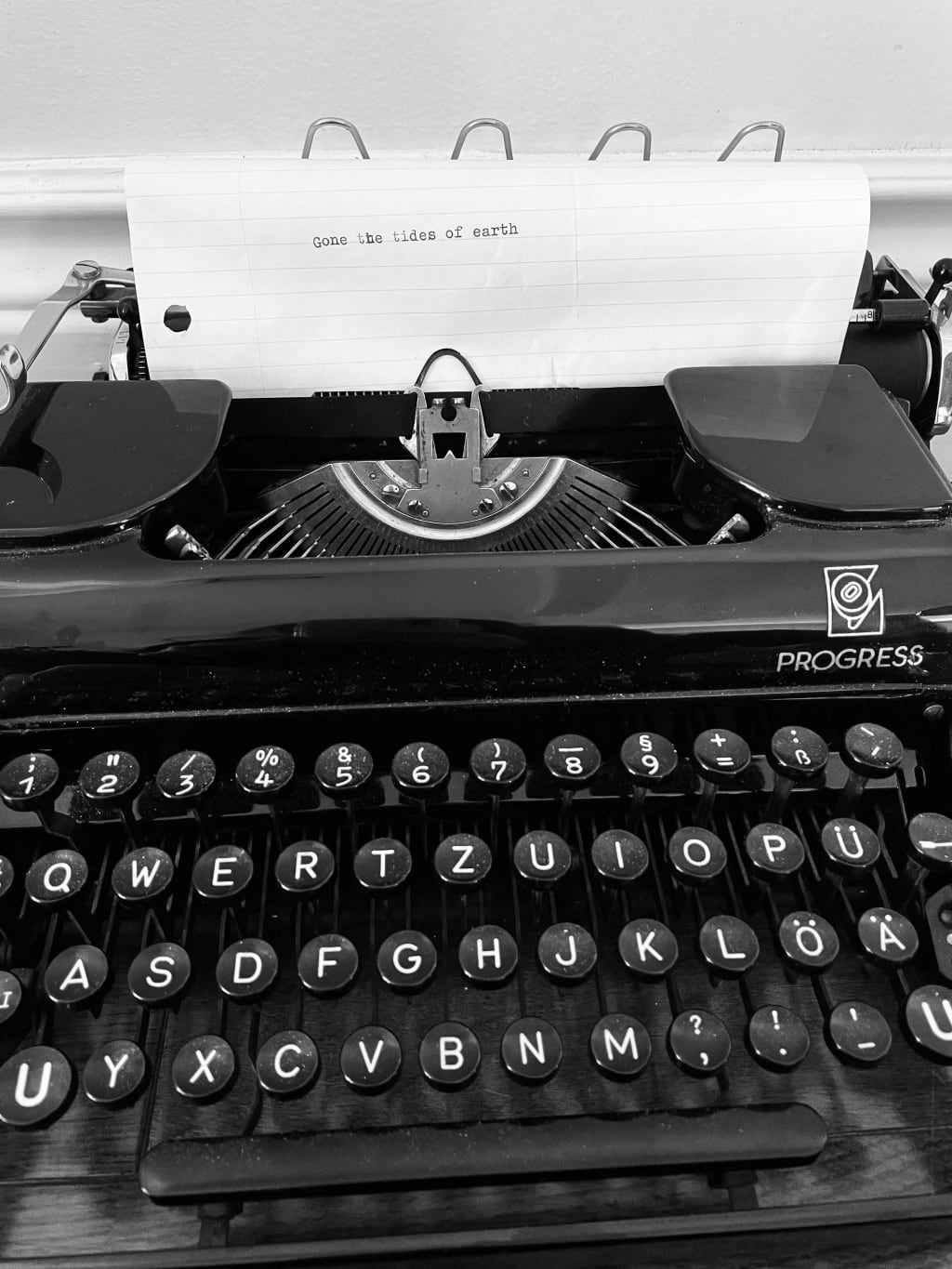

Gone the Tides of Earth

Chapter 7

By auspice of the crone, I wake next morning at first light - sound of a distant bell erupting into the room, thrice chimed, empyrean, metallic and ponderous over the village, out upon the bay, dawn rays flitting onto the terraces. For a short while silence resumes thereafter, peaceful in its ere regnant holy beauty - two minutes past the short abrupt noise hammers out, again in glory of reverberating trifecta. Whence soon it tolls anew - that loudest, foulest, unholiest of alarms - I am by then quite awake; then peals a last as if for a measure of reassurance, in series of three vindictive, tinnitus-inducing strikes.

I know the bell; its composition bronze alloy worked into the shape of a hoplite shield by ancient metallurgists. Long as life it had hung in a makeshift belfry converted from an owlery, located below the mountain path plateau. Folklore stated the bell itself was older than the Battle of Marathon, that back in those renowned olden times citizens of the settlement struck it hours long, all day and night to muster Peloponnesian armies for war, having witnessed Persian ships sailing north in the Aegean.

Well alert I get out from bed, open the door to a breeze flying soft as silk, cool despite morning warmth. A sparsity of light enters the room, sun not yet high enough for sunlight to breach the stone barrier. In the threshold I stand nude in supple, breezy zephyr, bask in radiant vitality of morn - a fineness which possessed purity and, if it were also an omen, such that I in premature awakening was harkened unto by auspices partial the crone, or mayhap divinity truly hers alone, it allowed me to feel confident in what I’d yet to do. For I could not yet bring myself to dress, I walked out into daylight, zephyr – felt that rather the moment was one to hold onto. Within me the softness embraced like universal swaddling cloth, sifted as oscillating grain; caressing as if infiltrating earthen vessel, coagulating like gaseous green energy kissed unto thine body and spirit of deepest serenity. Then after the next moment whence sands of the hourglass of peace ceased spill, despite newfound courage remaining as its deposit - impassioning me with raging fury of the storm - I gathered my collective senses, got dressed, went out the chamber and up the spiral stair headed towards the smaller terraces directly above.

The higher terrace was thin, empty except for a table with few chairs. Next a lane led upward between edifices either side, old houses of ruby, caerulean and canary rectangulates with auburn-tiled rooves. Its granite floor had a bland, cream-coloured shade noticeably refurbished no longer than a couple decades ago. Past next set a farther stair diverged where the others ended, around the side of the structures attached to the overarching goat-pass. Up those stairs ambled away from terrace, going up jagged limestone steps. Atop came upon row of marble pillars lining precipice; in center of the floor a squared plot bedded with soil, a little garden of lavender, mint, lilac, orchids. Along edges of the garden were a couple wizened elms, cypress trees. Throughout the plot were Grecian, columnar-styled lattices, a gate-like trellis. Beyond one more upper terrace there were no longer any staircases or direct thoroughfares in the village. Well to the contrary, but a single exception: an esoteric flight hidden at the flank of the shell of a cubiform shop, an old, rickety, plank-stripped tread that led to the outskirts of the town towards the bluffs and hills; it led also behind to a secret division of village built out of wood against the same dark inner walls which concealed the lustral basin; those such wooden hovels, long ago deteriorated, had been places where the proprietors of prohibited locales cut teeth, luring unwary, youthful Hellenes unto illegal dens with the promise of sinful pleasures, illicit fornication, ecstasy by mutilation, abnormal sensations, et cetera.

Where I stood could not see upper levels from underneath the imposition of cubiform, clay-and-thatch edifices. Logically, I abandoned the scaling of lesser stairs, circumvented the terrace for its extremity where a rotted oak bannister separated about the middle, and yielded entrance onto the crescent goat-pass. As ambling up the long steps the sun’s heat was pressing, humidity weighed hard. Heard seabirds out upon the water, saw them plummet, curtail and drift over the bay. Musts, salt of sea and smell of moist dew carried in the wind. Nearby structures shone, dazzlingly bright and each colour bolstered with fullness of morning light. Day had suddenly become hot, still, although clear and beautiful as well. During climb had not spotted any living trace of domestic life, namely not the crone, cats anywhere within the walls.

I thought I knew where she would be, the wise old patronne; where she tended to prepare meals, especially on days when there were rations enough for well-rounded dishes. From the goat-pass I turned onto a long, thin stair and descended; led down into small square at the middle of a dozen open-faced, inverse structures. More narrow, short flights went from behind those structures up, down to other proximate areas on different levels. The confined plane seemed to be a crystal heart of the village, way the light refracted its coloured domes, sparkled off whitewashed structures. Xekinóntas Pnévma was what the locals of old called it, which the crone translated to something along the lines of Spirit’s Starting. Indeed, it felt to be a place where one might start, that one may even begin again and eventually could end.

Many buildings in the square were old stone; each faced in, had a short roof and three walls. The fourths were broader, open-faced like setups of theatrical productions. The rustic square tucked in the village, original module, was like a bit of forest which never grew to breach the canopy. I stood in the square, below foot of the stair on cracked tiles. At its centre was an ivory fountain chiselled into the shape of rolling waves, that boasted centrepiece of a ship-terrorizing kraken; rim of the fountain was overflowing with moss, mildew, greenish rainwater. Within silence, I sensed presence nearby; understood intuitively, felt beneath the bones - somewhere close the crone must be - so I walked closer, stopped, gazed around to inquire. An interior of a structure between two alley staircases held the components of an age-old blacksmith workshop; rusted tools concealed on a wooden workbench beneath swaths of spiderweb, dust, smelting furnaces, hearth and a bronze anvil on a rot, straw-matted floor. Across the square, inside the largest lodge - a low, long and shadowy whitewashed cubiform - was a mess-hall of old. Support beams held up its backwall, frayed frescoes recovered from crumbled walls portraited, a stained-glass window centered near shabbier reticulate openings. Thinner pillars supported the edge of edifice, out in the open were adjacent benches, an oaken doorway behind. I walked across into the grey, drafty dimness, it was more pleasant in the shade, out of the sun.

Distantly I heard the calm, swishing roll of the tide, mimic to the white noise of olden radios, televisions. Sunlight splotched the unglazed glass of grime-smeared windows. Gone past the tables, I turned an old bronze knob and opened the door; rusted hinges creaked as it rolled inward, door on a slight decline so that the bottom trim scuffed the stone floor. When open I saw into the vestibule, a dim room with long sectional counters, iron grates in the walls, also between the floorboards, in the ceiling.

‘Hello Henry,’ the crone said, as I stepped forth.

‘Good morning,’ I replied, through the threshold.

‘Sleep well?’

‘Till a certain point - couldn’t let me sleep any longer, then?’

‘If I had you would’ve slept all day. And today is a special day.’

‘How so?’

‘Oh it is a day of forwardness, offering. To thank the gods, bid farewell to summer’s grace.’

‘We aren’t yet long past midsummer.’

‘No, but it will go fast. Then it will be gone. Today is special.’

‘Understood.’

‘You must be hungry.’

She had been preparing ingredients in a hand-turned walnut bowl. Her at the back of the kitchen, I could not see what was in it. As she spoke then lifted it, turned to go out and walked past me through the door. I followed her, sat down at a bench outside.

‘Eat,’ she insisted.

‘Ladies first.’

The bowl was partitioned by wooden dividers into eight segments; in sections were slices of apples, pears, oranges, olives, grape tomatoes, spinach leaves, salt & pepper, and a light icing for dipping. After eating mine stomach felt nourished nice and well, clean for change. The crone got up, went back into the kitchen, returned swiftly with two bowls of whipped goatmilk yogurt sprinkled with granola. We polished that as well, washed it down with tall glasses of cool, freshest water.

‘You like it here?’ She seemed happy, smiling upon the morn place. ‘This was an important part of our village,’ the crone said, ‘many families of the commune used to come together here. Yes, here we would gather for dinners and to cook, wash, eat, talk, laugh together; yes, indeed.’

‘Better than the ideals and practice of suburban mealtime,’ I said. ‘Everyone was trapped in their own little world, within single minds. We wanted everything to feel good, since such little actually did. We’d forgotten what truly made us feel well.’

‘You mean quick fixes?’

‘In and of the whole. Technology, modern advances, social currents did well away with any notion of community. Most people lacked ethical considerations, their entire thinking bound up with self-interest. We forgot how to come together for what really mattered, and the things that could, that was the main thing.’

‘Some lost what mattered most. West was just a fraction of the whole. Some kept it, such as it were here. Please know this, Henry: there will always be a heart out there, you always can find it.’

‘Okay,’ I replied.

She smiled, ‘This you must feel to believe.’

‘Then I do.’

‘You’re a good man. You must know that fault did not only lie in what people forgot. Though most realized this, started to figure it out but did so too late.’

‘Not only what we ceased doing or forgot, because we stopped caring. Partly because people did not discover life for themselves. Prescribed for us it was through boxes, over soundwaves and in print. Dear lord did we ever subscribe.’

‘That was the way of life in the New World.’

‘No, it was within time. Life stayed the same - substance changed. Time beat on as humanity disintegrated. We talked of necessity for change, made steps to meet the grain. When something powerful has set in the blood, metastasized, what’re the actual chances for the eradication of that disease - of cleansing it from DNA?’

‘Is that the thing then?’

‘Creatures evolve to alter or destroy things that they can, nature remains.’

‘Is that the curse?’

‘It’s mine.’

‘Well, it seems you’ve summed up the crutch of the former societies of contemporary Western Civilization.’

‘Might we conclude that we grew stagnant and, like water in that fountain, stuck in volatile stasis?’

‘Maybe, not anymore. Earth is restarting - what humanity left reborn anew.’ The next thing she said came upon quite unexpected, ‘I know you’ve something important to say - you’ll tell me now, please?’

I said nothing.

‘You have for some time had something troubling you.’ She looked at me maternally. ‘You must speak of it no matter what - for I sense an undertow within you.’

Feebly, I sighed.

‘You leave this place?’

‘Yes,’ I concurred.

‘Would I be correct in assuming tonight’s meal shall be our last?’

‘I’m sorry you’ve found out this way. I couldn’t think up a decent way to tell you. You have been so good to me.’

‘There wasn’t a good way for finding out.’ She stood up, wiped her gown. ‘I wish you told me this earlier.’

The crone gathered the bowls candidly, walked back into the kitchen. I sat there looking across the square, at the bit of crystalline sea I could see beyond the structures. After a while she did not return, I got up, went up the staircase. Then I thought better of it, ended up redoubling my step for a stair down from the old forge. A good part of the afternoon, I wandered around the village. Later I stood out on the grand terrace, where I felt the feeling upon the evening before joining the crone in lustral basin. From there I wandered the corridors, chambers again, considering frescoes, dank walls, unique windows, and up to the hovels hidden against inner walls that had been opium dens, brothels, the wood rotten, rooves painted black with grimy reeds. In the late stage of things, before returning to quarters I went along the beach, strolling sands westward to where could see the hills, bluffs, where revelled the ichorous bastion from a distance - golden, glorious as it was in the fading sun - thinking to myself whole while through.

The light in the sky softer, sweat is cold and damp when I get back to the chamber. The door is open as I left it, and underneath the low, corner-pressed bed a ceramic wash basin, soap dish, folded stacks of cloths, towels. After I undress to rest for a while, when I wake the light, retreated farther on the horizon, is dark gold tinged violet-crimson. The wind is strong, dark tides break heavily on the shore, temperature cooler. In vague heat I inhale deeply in nostrils the salty, earthly musk. Next rise from bed slow, gentle, and kneeling reach under to grasp an eighty-litre rucksack; it was the same pack that had been with me since the start, brown and green with navy blue. Mainly it is filled with articles of clothing; sweatpants, khaki, a blue-yellow hiking raincoat, t-shirts, button-ups, woolens, socks, briefs, obsolete cash, coins, and a dozen especially placed, prized keepsakes and final necessities; displaced letters, copies of War & Peace, The Sun Also Rises, Heart of Darkness, a multi-tool, wallet with ID, a photograph in pearled-oval picture frame.

Soon I look about the bedchamber - where idled, I turn around full on the spot, taking room in for a last time - and I thought enough that I truly felt it: remnant of the same sentiment that night of the lustral basin, whence felt to be in the presence of gods, as if something from then out on the terrace and in the room now was scrying out a future, husking a ghost from a shell of the past. Fearing I had lingered too long I gathered pack, lashed it over the shoulders, moment for good measure, then headed out the door. The door I left ajar in the threshold, swept away up the closest stair to make for larger steps connected with the goat-pass.

Clouds coloured velvet had disappeared once I departed the goat-pass, and as I crept down the narrow flight unto cobbles of the quaint square. The open-faced structures that before basked gold, even cast in shadow hints of translucent redness sheened upon their grain whitewashed. Arriving at the bottom I disembarked, walked along towards the mess, away from the forge, decrepit fountain. Beyond the pillars underneath edifice I laid up the pack on a bench, then into the kitchen. The crone was in there.

‘Have you been saying your farewells?’

‘I went around a while then napped for a bit.’

‘It is wise that you intend to leave in the night. You will bear it better that way.’

‘I take my leave after dark.’

‘I’m making a fine feast for us.’

‘What’s on the menu?’

‘Look for yourself. I hope it is alright.’

‘Thank you. It’s well above and beyond.’

‘Nothing.’

As we spoke, I could tell everything from earlier was behind us.

‘Go out and wait, Henry.’

Shortly we sat at a bench eating tendrils of grilled octopus prepared with balsamic vinegar, olive oil and a yellow paste like hollandaise. As an appetizer we had raw oysters, salad made with spinach and garden vegetables. To drink were vintages of well-aged red, their storage a dank cellar below the mess-hall. Each course was rich with flavour and the wines robust, lasting much longer than food. Firmament had gone dark by the end of meal, save a spectre of texturized deep purple egged in the forming pitch, kissing the horizon. A ghost of light clung to marble of the artisanal fountain, the structures shadowed grey and square black. A strong breeze had picked up into a brisk wind, stars already lighting the canvas of night, spread widely throughout ether.

The crone collected a couple miniature candelabras, four tapers and equal pillars, yellow, white, red, olden candelabras sterling-silver. Insides of pillars were halved hollow, flimsy rims of wax like earthen barriers of dug-out motes. The old woman placed them at the corners of the benches and lit the wicks, face in shadows.

‘When light cannot be found we must illume our own,’ she said. ‘So it cannot be of peace. Tell me why you leave.’

Long, I took in a deep breath, knowing not to mince words, ‘To see things with my own eyes and learn how to feel again.’

‘That comes from within, not without. Are you afraid?’

‘Maybe.’

‘The paradox of human spirit,’ she said, ‘fearing what might find, yet having to go, nonetheless. Let an old woman tell you something, once last: you will lose. But since you cannot be sure when, how, mustn’t fear what might never come to pass - or else you will forget to live. You must rid yourself that unshakeable feeling, or Henry will not I think fare too well. What I mean most is that the worst always remains ahead of us, does not mean it is unconquerable. One must progress, take best care to never succumb.’

‘I’m sure I’ll be fine,’ I said, raised my glass. ‘Thank you for the wisdom.’

‘What your about to do goes to the very extent for which courage can carry you. The remainder is up to spirit, mind, body. One must never practice self-delusion - I’ll tell you what you must do. Whatever notions about yourself you fancy as innate, you ought get rid of right away. You are wise yourself, so I say no more. If you are not willing to do away with the mindset that certain ideals, actions are what render you you, then you may not go far in that crazy hell before finding self dead. What I try to get across, because you are dear, is the necessity to be prepared for anything - and don’t ever lose yourself.’

All of the bottles on the table were empty, I got up, went down into the cellar crawlspace. Stumbled a bit on the rickety stairs, later fumbled the spirits on the racks. Below in the shadowy dark of the stone floor a spectral, dimly visible a stream ran through the mortar. Grabbing a fresh vintage, I went back up, out onto the courtyard.

‘This will be my last.’ She stood, disappeared into the kitchen, coming out after a moment with swaths of parchment-wrapped objects swaddled in tattered cloths. ‘These are for you. Don’t forget.’

We sat and drank the last glass in a silence inert. Like her, I was tired as well, though in a manner caffeinated as I felt the adrenaline of what would come close. For when I would leave, going up to the plateau, along the beaten trail through the far plain, into the woods, then beyond to the mountains in the distance.

‘You never told me about her,’ she said, ending the silence. ‘About your parents, a little. But never of her - the one who you stayed with in Paris and came together across Atlantic. In your cups, you’ve said only this much.’

‘Much time has passed.’

‘Long ago or not, did you leave her much as she left you?’

‘Yes.’

‘Then no bitterness can there be apropos any of it.’

‘None.’

‘Good that you are smarter than most men. Why did she feel compelled to go?’

‘There was a history - an entanglement of pain, our love. For too long my suffering had belonged to her as well. Whatever her reasons, I understood.’

‘Never is it anyone’s fault. Romance is a field I never cultivated too seriously - I cannot say I regret this. You Westerners in love, and yet most people believe mine are the fanatics. So finally the time came, in the end it came to be that you lost each other.’

‘Have we not all felt our share of losing?’ I quipped.

To that we raised a toast, cheersing the glasses, drank a libation. After that, for a moment it was quiet again.

‘Alas, it is time that I retire. From here you will go on your own.’

‘Is there anything to be done before I go?’

‘Myself, I require nothing of you. You are a fine young man. The world is weak, there are not too many good.’ On her feet, she leaned over the table, kissed gently my brow. When she withdrew, reposed in the night air, seemed like a shadow bust sculpted of darkness. ‘You’ll do wonders, I think.’

‘Can I walk you down?’

‘I am alright. Stay, process here what you must beforehand. Be careful, intelligent as you are. Farewell, Henry Owen.’

‘Goodbye, goodnight.’ I stood. ‘Thank you for everything.’

She took off across the courtyard, resounding steps diminishing upon the stone. I grasped the last bottle of wine, drank the rest down - watched the wicking candles, waxes oozing like molasses, flames dim, feeble, guttering in the midnight breeze.

Out on square I looked, by then she was gone - we were both alone.

About the Creator

James B. William R. Lawrence

Young writer, filmmaker and university grad from central Canada. Minor success to date w/ publication, festival circuits. Intent is to share works pertaining inner wisdom of my soul as well as long and short form works of creative fiction.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.