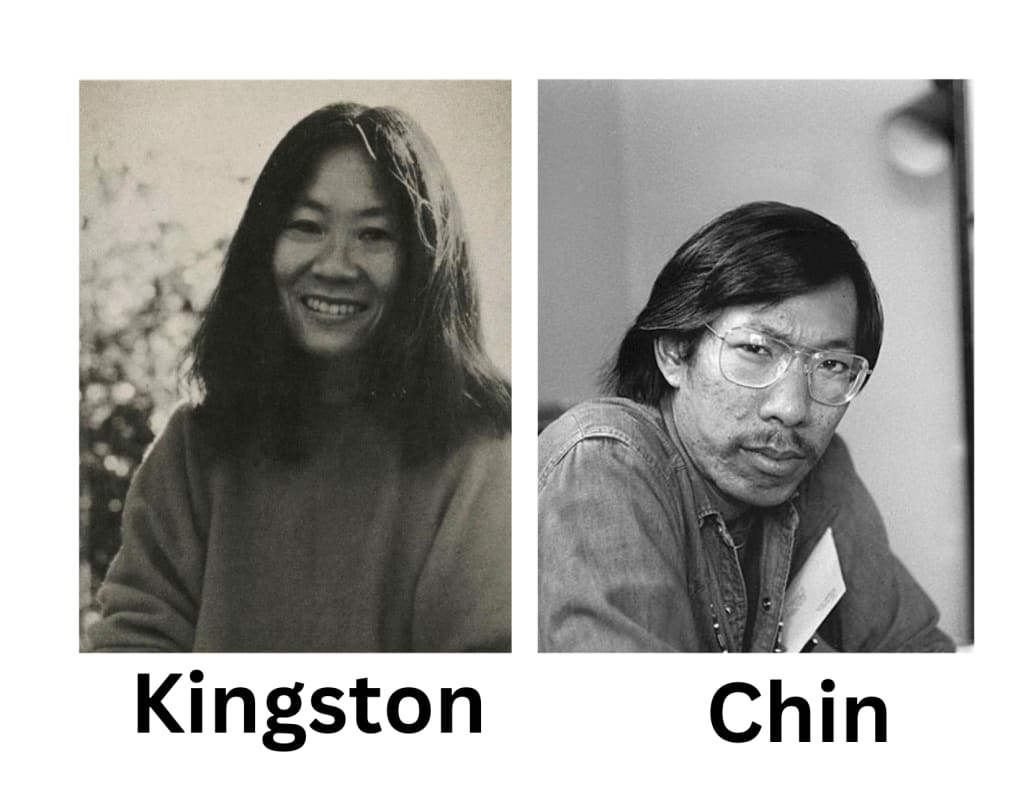

Frank Chin and Maxine Hong Kingston:

Forever Locked in Debate

In Asian American Writing there is a war going on between men and women. It is an argument that places women in the position of popular minority writers in a white dominant culture, and men in the position of underdog trying to get a fair break in the world of words. This position began over twenty years ago with two wonderful Asian American writers: playwright and pioneer writer Frank Chin; and multicultural feminist and fiction writer Maxine Hong Kingston.

Frank Chin was an established Asian American writer before Maxine Hong Kingston came on to the scene. His plays were the first by an Asian American to get produced off-Broadway. He paved a road for a new generation of Asian American writers, and in the process, began to formulate his own arguments on feminized stereotypes of Chinese American men in white dominant culture, and the Christianization of Chinese-American History (Young, 100).

He feels that Asian American men are seen as “womanly, effeminate, devoid of all the traditionally masculine qualities of originality, daring, physical courage, creativity” (Cheung, 110). To right the historical record, Chin wants writers to pursue “generic purity and historical accuracy" (Cheung, 112). “Many Chinese American male writers paralleled Chin, who like their Euro-American counterparts, tended to concentrate on the accomplishments of men thus relegating women to a subordinate role” (Young, 103).

Within their work, many of these writers also contribute to stereotypes of women, while they accuse Asian American women writers of perpetuating stereotypes of effeminate men. Two of these images of Chinese American women are the submissive obedient slave girl and the ever-popular dragon lady (Young).

With his fellow Asian American writer Jeffrey Chan, Frank Chin edited Aiiieeeee, where his arguments about masculinity were first presented and published. They use heroic writings, predominantly by men to emphasize the heroic masculinity of the Chinese American man, and women like Sui Sin Far who criticize a white dominant society to prove that those who are real, those who both criticize and embrace U.S. society are not as easily known as those they claim are fake writers.

According to the real Asian American writers these fake writers embrace the cultural issues of the U.S. without knowing or understanding those issues of their home countries. They perpetuate stereotypes of Asian Americans and play into white dominant ideas in order to continue to publish their own work.

The arguments between Chin and Kingston began after Kingston found out her book The Woman Warrior was going to be published. She contacted Frank Chin by way of letter correspondence to ask if he would approve and endorse the book for her. He thought her work was moving and lyrical, but felt that he could not endorse it.

The book, originally conceived as a work of collected fiction, was to be published in the autobiographical genre of memoir, which he considered fake and appealing to white dominant publishers. Chinese Americans don't write Autobiography. He said, "I want your book to be an example of yellow art by a yellow artist [...] not the publisher's manipulation of another Pocahontas” (Iwata, 2).

Chin also accuses Kingston of causing too much confusion between the real and the fake by using mixed genres of fiction and autobiography. Kingston replied that she was “experimenting with genres, blending the novel and the memoir”(Iwata). She questioned her own and everyone else's ability to know the difference between the real and the fake when it was applied to these stories (Iwata, 2).

Chin refused to see the complexity and multiplicity in her viewpoint as something good. He saw it as harmful to confuse a white dominant society that knew next to nothing about Asian American cultures in the first place. Looking back we see that he was correct in this assessment. Too many Americans misunderstood the book.

In 1977 Diane Johnson, a white feminist, published a review of The Woman Warrior in The New York Review of Books. Her review clearly shows that she had an obvious lack of knowledge of both Chinese and Chinese-American culture. Particularly glaring was her commentary about Asian Americans in fourth and fifth generations still unable and unwilling to speak English in the land they had made their home.

This review sparked a response by Jeffrey Chan (Johnson, 79-83). Chan refuted Johnson's knowledge of Chinese American society and made his point well. He argued that fourth and fifth generation Asian Americans knew, understood, and used the English language well. The mistakes she made within her review should not be overlooked (Chan / Johnson 84-87).

In her response to Chan's response, Diane Johnson admitted that she was not a specialist in Asian American studies, and there was much about Asian American culture that she did not know, although she continued to claim that her statements about Chinese American families having fourth and fifth generations unable to speak English would seem to be a white dominant cultural viewpoint.

As she says, the facts were currently unchallenged or disputed by any but Asian Americans who know the true story, but were powerless to get others to listen to them.

Johnson does adequately refute Chan's point about Kingston's use of the word guai. The multiple meanings of this one word fueled many a debate, but provided no clear answers for a white society who didn't know any better (Johnson, 86-87).

Guai loosely translated as ghost could take on many forms, both negative and positive. Chan denied this. He believes that the word designates a negative image generally applied to whites. As in white devils. Kingston herself said she saw the word as complex, representing both positive helping ghosts, and negative ghosts. She left it open to interpretation by the reader (Iwata).

This Kingston-Chin argument on paper first moved into the public realm in 1989. It took place in Honolulu at the “Talk-Story" Literary Conference held at the Mid-Pacific Institute. Kingston attended, but Chin did not. The panel was full of Chin's supporters, and they trashed The Woman Warrior so badly that a shy Kingston who was in the audience, stood up to defend her work (Iwata).

Feminists supported Kingston's work, but she continued to be misread by most, if not all, Euro-American critics. Even today, there are those who misread her, and may continue to do so for a very long time.

She says:

"I do not think I wrote a negative book as the Chinese

American reviewer said, but suppose I had? I'm certain that

some day when a great body of Chinese American writing

becomes public and known then readers will no longer have

to put such a burden on each book that comes out. Readers

can see the variety of ways for Chinese Americans to be."

(Kingston qtd. in Li, 182).

In 1989 Chin wrote a parody of The Woman Warrior that is placed as an afterward in a collection of his short stories called The Chinaman Pacific and Frisco R.R. Co. He called it “The Unmanly Warrior" (Li, 191 192). His use of Joan of Arc as the hero of the piece was guaranteed to incite anger within feminist groups, as well as to shoot down Kingston's work.

Kingston responded as she always has: through her writing. She published her third book called Tripmaster Monkey: His Fake Book. This book contains the Character Wittman Ah Sing, "a would-be macho Chinese-American who has the charm and guile, but also the nastiness of the proverbial trickster Monkey" (Lowe, 1). He may be an amalgamation of Kingston, her brother, and Frank Chin. Persons who know Chin swear that the character talks just like him, and continue to read the piece as if it were Chin (Mukherjee 279-281).

Euro-American reviewers continued to misread Kingston. No critics or reviewers understood the significance of the title Tripmaster Monkey: His Fake Book, which quite possibly is a tag for Asian American writers and a few others who would understand the reference to the ongoing debate with Frank Chin.

When asked, Kingston says that's not true though. The title meant several different things, including clues to the trickster as a character in minority writings, who “operate[s] as intermediar[y] between the cosmos and mortal men” (Lowe 2).

This monkey is perhaps most fit to represent individuals caught between two or more worlds, with his own position of “one foot in heaven, one on earth.” (Lowe 2)

We must also consider this possible image as an aspect of the Chinese Monkey King. This Monkey King is “extremely smart, and capable. [. . .] He can transform himself into 72 different images” (Yuan).

It sounds suspiciously like the position of any ethnic minority in the United States. To exist, one is pulled in so many directions it is easy to forget who you really are. Kingston actually says toward the end of the story “Dear American monkey. Don't be afraid. Here, let us tweak your ear, and kiss your other ear” (Kingston qt in Lowe).

Perhaps this is a glimpse of the parent who knows trying to instruct the unruly child who does not know. It is indeed easy to see that Kingston does know something about the Chinese side of her, and Chin has not looked beyond his narrow arguments to see that she is well aware of her Chinese heritage despite what Chin has stated about her inability to distinguish the real from the fake.

In The Big Aiiieeeee Chin presents a negative review of Kingston, Amy Tan, and Henry David Hwang. He mentions the historical inaccuracies that he sees in all their work, but he remains locked in debate with Kingston and her work because they are seen by other American writers and critics as each other's binary opposite. This is perhaps a glimpse of the Fake rather than the Real. It has been the academic community who is responsible for dividing Chin and Kingston into those opposites.

Instead of closely studying Chin's work, he is easily placed in an argument about heroes and stereotypes, with as narrow and clear a sense of his position in this argument, as his view of Kingston and her position in writing. Kingston represents a feminist, multicultural, messy argument that Chin just cannot tolerate.

In truth, both Chin and Kingston are good writers, knowledgeable of their own experiences in the world, and have a mutual respect for each other that is often overlooked. They also both share similar ideas about stereotypes and the perpetuation of those stereotypes within our culture.

Chin currently holds the unpopular position, but that was not so true in the beginning stages of the argument. Twenty years ago academic theory would not have allowed for a position that did not lead to one very specific thought or idea.

To have a theory that led to many possible answers was not good theorizing. Even today in every academic discipline, we see those singular theories. Things have only changed since women's studies; gender studies, racial studies, and cultural studies departments have become well known on campus.

Within these disciplines it is recognized that singular theories limit and narrow the study of a field, so that getting at the truth of anything becomes literally impossible.

Chin's singular theory may have come out of his position within the academy before multiculturalism and multidisciplinary ideas gained strong support. But if we were to expand his arguments about the real and the fake to include women equally, we might be able to argue that his views on stereotype and stereotyping do actually lead to a multicultural position.

One big problem is that he insists on writers of the real because of the capacity of a white dominant audience to misinterpret a work even though it may be presented as fiction and take it to be a truthful representation of a particular culture. The problem is that this takes away from fictionalists and all creative artists. Chin is right when he says white dominant society looks at any minority work as if it were the true history of that minority.

We see it happen when Kingston's work is published. At first, Kingston denied that Chin was right, but the more time that went by, the more she saw that everything he had predicted would happen with The Woman Warrior, did happen almost exactly as he said it would. Her work was presented to an American public wrongly and then misinterpreted by both critics and readers.

His clear-cut argument about stereotypes can apply as equally to women if Chin were to look at it. Just because he does not choose too, it does not mean that this position isn't possible. It simply means that for Chin it is impossible to support that position while he is fighting for Asian American men.

On the other hand, that narrowly defined viewpoint leaves out just about anything relating to women. He makes a huge deal out of the fact that within the story of Fa Mu Lan, Kingston gives her the tattoo originally found on the General.

He fails to see that the Confucian obligations of family, duty, and responsibility apply to women as surely as they apply to men. He is after all, the one who insists that every human being is a soldier in the war of life.

Many of his arguments contradict each other. He fails to dwell on stereotypes as they apply to women, and refuses to acknowledge that women are in a worse position than men. Critic Amy Ling tells us that for women brought up in the old Chinese tradition that for eighteen hundred years codified their obedience and submission to the men in their lives—father, husband, son-a tradition that stressed female chastity, modesty, and restraint [. . .] any writing at all was unusual, even an act of rebellion. (Ling, 219)

“Finding one's voice and telling one's stories represents power (Ling 235).” This is a rebellion that Chin just cannot allow to happen. It will take too much away from Asian American male writers. His immovable stance has forced Kingston to raise the question again and again about the responsibility of the artist. “Why must I represent anyone besides myself? Why must I be denied individual artistic vision” (Li 182)?

Does this problem lie with Kingston, or does it lie elsewhere? White dominant eyes see very few pieces of literature from other cultures, or from individuals caught between two or more cultures, so perhaps the first thing we do is associate the writers with what we take on as the real story of a particular culture. We are the ones who put minority writers into this position of having to bear the weight of explaining their culture to those who haven't even begun to try to understand much that is different from dominant society.

The argument remains a large debate within the Asian American community, but it is unclear how many white dominant members of the U. S. even know that this argument exists. Maybe more writers and students of literature know about the argument today because of both Chin's position, and a more recent multicultural multidisciplinary approach to literature and cultural studies.

In 2000, Chin declined yet another panel invitation because Kingston, Hwang, and Tan were also going to be there. While many have actually wanted to see them together in debate, which has never happened. Perhaps all we will get to see is their responses to each other within their work. They influence each other whether either of them admit to it or not, and it does influence the material that they chose to write.

It is true that Chin has launched some very gendered attacks on women, while trying to further the cause of Asian American men. He steadfastly refuses to acknowledge that women continue to be found in writing, television, film, and the arts.

Chin doesn't necessarily practice what he preaches about Asian American women and their perpetuation of ongoing stereotypes. He is just as guilty of perpetuating ongoing stereotypes about women as seen through all of his writings. He “depicts male characters who are sexually potent or who experiences their manhood in violent and traditionally American ways"(Lim 243).

Within Chin's work we see stereotypes of Chinese American women as well (Young 99). “Despite the tradition of repression and devaluation [...] Chinese American women writers have demonstrated their talents, expressed their concerns [...] and have contributed [greatly] to American literature (Ling, 236),” even if Chin does not believe that.

But he is correct in his argument about stereotypes of Asian Americans. They continue on throughout our popular culture. There is great re-visioning and creation of stereotypes by the dominant white society.

We see it happen time and time again. The problem is putting the onus on the writer to break through those stereotypes. People who agree with areas of his argument but not with his methodology suggest that what needs to be done should perhaps be “ to reclaim cultural traditions without getting bogged down in the mire of traditional constraints, to attack stereotypes without falling prey to their binary opposites, to chart new biographies for manliness and womanliness" (Skanda 112).

One Kingston supporter, Native American writer and feminist Paula Gunn Allen understands exactly what Kingston means when she speaks of trying to write in the space in between non-fiction and fiction. She compares that space to Gloria Anzaldua’s thoughts on La Frontera, that borderlands space being explored by Latina writers as well.

It is that space where the “sheer multiplicity of clashing worlds that constitutes the everyday experience of contemporary ethnic writers” (Skanda 335) gives them multiple layers of life experience to work from, enriching their work in ways that a white dominant writer might not ever be able to achieve. It will ultimately enrich all our lives when this kind of work will be available and easily accessible to us all.

Work Cited

Chan, Jeffrey Paul. “The Mysterious West.” Critical Essays. 84-86.

Chan Jeffrey, Frank Chin, Lawson Fusao Inanda, and Shawn Wong (Eds). The Big Aiiieeeee!: An Anthology of Chinese American And Japanese American Literature. NY: Meridian-Penguin. 1991.

Chang, Jeff. “Up Identity Creek.” Colorlines Magazine. (Winter 1999).

http://arc.org/C_Lines/CLArchive/story1_3_06.html

(2 April 2001).

Cheung, King-Kok. “The Woman Warrior Versus The Chinaman Pacific: Must A Chinese American Critic Choose Between Feminism and Heroism?” Critical Essays. 107-124.

Chin, Frank. "Come All Ye Asian American Writers of the Real and the Fake.” The Big Aiiieeeee. 1991.

Goshert, John. "Frank Chin In Not A Part Of This Class! Thinking At The Limits of Asian American Literature.” (2000).

http://social.chass.ncsu.edu/jouvert/v4i3/gosher.htm (3 April 2001).

Huang, Judy. “Untitled Chin Kingston Debate."

http://www.dartmouth.edu/Historyl (3April 2001).

Iwata, Edward. Is it a Clash Over writing Philosophies, Myth and Culture? Or is it Just An Anti-feminist Vendetta? No Matter. The Long Feud Between Two of the Brightest Lights In Asian American Letters Has Reached A Boil. What's the Dispute Between Best-selling Author Maxine Hong Kingston and the Man Sometimes called the Chinese American Norman Mailer, Playwright Frank Chin? Why are They...Word Warriors." LA Times. (June 24, 1990. Pg. 1). Periodical Abstracts. April 3, 2001.

Johnson, Diane. “Ghosts." Critical Essays. 79-83.

Reply to "The Mysterious West” Critical Essays. 86-87.

Kingston, Maxine Hong. The Woman Warrior: Memoirs of a Girlhood Among Ghosts (1975-76). NY: Vintage-Random House. 1989.

“Cultural Mis-readings By American Reviewers” Critical Essays.95-106.

Li, David Leiwei. “Re-presenting The Woman Warrior: An Essay of Interpretive History.” Critical Essays. 182-203.

Lim, Shirley Geok-lin. “Twelve Asian American Writers: In Search of Self Definition.” Redefining American Literary History. 237-50.

Ling, Amy. “Chinese American Women Writers: The Tradition Behind Maxine Hong Kingston.” Redefining American Literary History. 219-36.

Lowe, John. "Monkey Kings and Mojo: Postmodern Ethnic Humor In Kingston, Reed, and Vizenor.” MELUS. (Winter 1996). Periodical Abstracts. (3 April 2001).

1) Nishime, Leilani. "Engendering Genre: Gender and Nationalism in China Men and The Woman Warrior." MELUS. (Spring 1995). Periodical Abstracts (3 April 2001).

Ruoff, A. LaVonne Brown and Jerry W. Ward, Jr. Redefining American Literary History. New York: MLA, 1990.

Shostak, Debra. “Maxine Hong Kingston's Fake Books.” Critical Essays.51-76.

Skandera-Trombley, Laura E. (ed). Critical Essays on Maxine Hong Kingston. New York: Simon/Schuster-Hall, 1998.

“A Conversation with Maxine Hong Kingston.” Critical Essays 33-50

von Walter, Yvonne. “The Ayatollah of Asian America Verses The Woman Warrior: Remarks On The Chinese American Literary War.”Twin Peaks. (15 Oct 1998)

http://www.unileipzig.de/-amerika/tp/tp_309.htm (3 April 2001).

Young, Mary E. Mules And Dragons: Popular Culture Images in the Selected Writings of African-American and Chinese-American Women Writers. Westport, Ct: Greenwood Press, 1993.

Yuan, Haiwang. Legends of Monkey King (1994).94).

http://www.chinapage.com/monkeyk.html (30 April 2001).

About the Creator

CL Robinson

I love history and literature. My posts will contain notes on entertainment. Since 2014 I've been writing online content, , and stories about women. I am also a family care-giver.

Enjoyed the story? Support the Creator.

Subscribe for free to receive all their stories in your feed. You could also pledge your support or give them a one-off tip, letting them know you appreciate their work.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.