History of Technology: How Enrico Tedeschi Saved the Guglielmo Marconi Collection

Enrico Tedeschi stopped the auction that almost scattered the historical Guglielmo Marconi Collection around the world in 1997

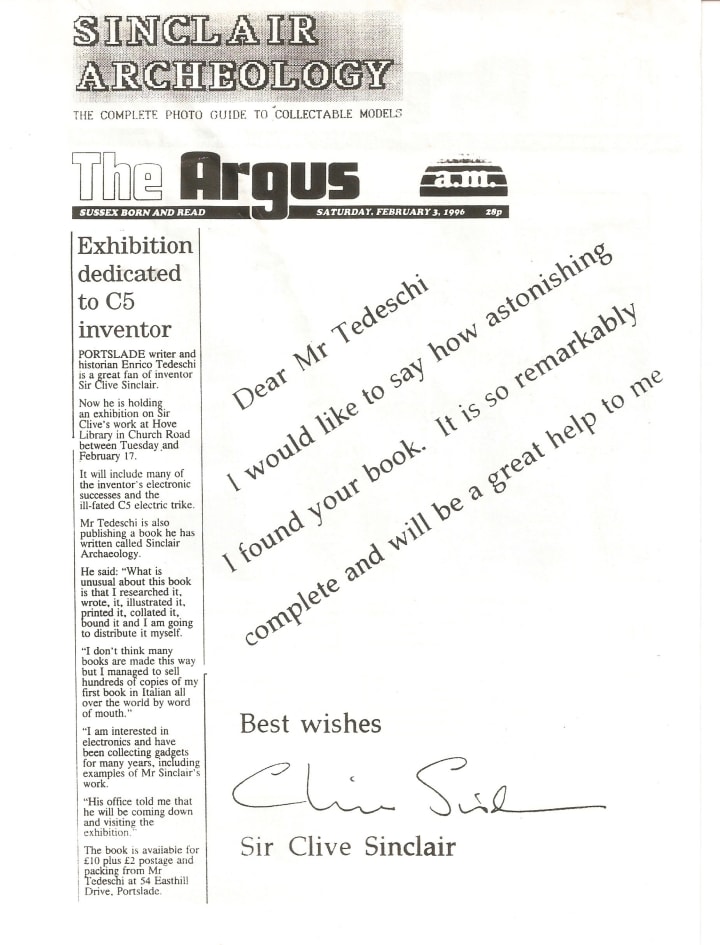

In September 2016, my quest to find a museum of vintage electronics in Brighton, England led me to the owner of over 10,000 artifacts. I found out he had held a short exhibition hosted at the Hove Library: The Sinclair Archeology.

Sir Clive Sinclair himself came down from London to Brighton since the exhibition was in his honor.

I was eager to meet this Italian man who seemed to be a walking encyclopedia of Dead Media. I wrote him an email expressing my interest in his remarkable personal collection; I wanted to learn about his journey toward acquiring it. I wanted to learn about him and tell his story.

I had read he offered guided visits to his collection in his own home, because he could not find any support to create a permanent exhibition.

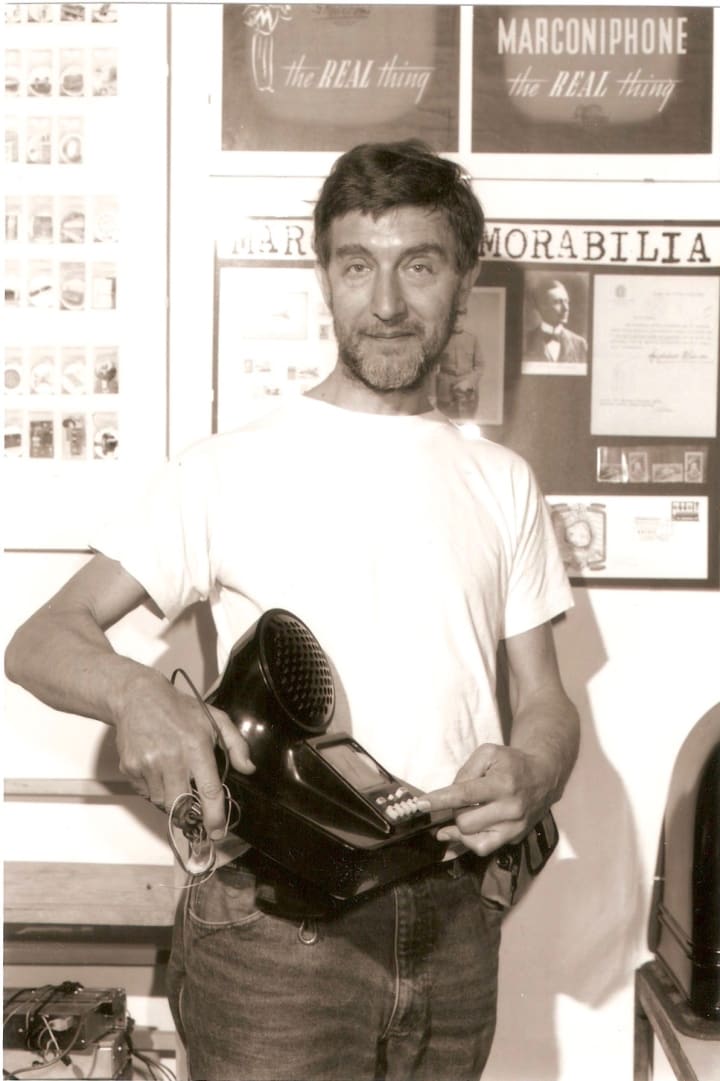

Enrico Tedeschi was an Italian-born independent computer software professional, dead media historian, writer, and a passionate private collector of electronics for over half a century.

He continued to do this until his passing in 2014 at the age of 74. Sadly, I was two years late.

In the tenth anniversary of Enrico Tedeschi’s passing, this is my tribute to a fellow dead media archeologist, with my gratitude to him for saving the Marconi Collection which now is part of the Museum of the History of Science in Oxford, England.

~~~

“My father would have loved to meet you.”

Richard Tedeschi, Enrico’s son, said when we met. He answered the email I sent to his father. He was kind enough to invite me to his home in Hove (one of the two main parts of the city of Brighton and Hove in East Sussex).

It was the home where Enrico had lived and housed his vast collection of vintage electronics and related documentation for over 50 years.

Richard was going to show me some of the items that belonged to his father, photos, and documentation from the family’s personal archive.

Richard was going to tell me the story of his father. The story I was so eager to hear.

~~~

Enrico Tedeschi was born in Rome, Italy in 1939. From a young age, he was curious about technology and showed an interest in radios.

He became an avid collector of Marconi’s radios, Sinclair’s computers, and a variety of other artifacts and memorabilia.

According to Richard's mother, Tedeschi’s widow, Enrico started developing his interest in radios and electronics at a young age, and he started collecting when he was only 10 years old.

Enrico Tedeschi in Italy: The Museum of the Radio

Enrico Tedeschi was working at a bank in Italy, but the strict environment was not for him. “He was trapped in a suit and tie,” his son Richard told me.

At the same time, Enrico got involved in alternative energies. He wanted to spend more time on his interests. “He left the bank and began to transform his interests and hobbies into his work,” Richard explained.

Enrico began selling Land Rover spares in a shop he opened in Rome. It was the first shop devoted to Land Rover spares in Italy.

In 1977, Enrico opened a shop and Museum of the Radio in Rome.

In 1981, he also began selling Sinclair computers, another of his passions, and again he was the first one. “There was nobody doing that in 1980. There was no competition,” his son told me. “He was always up-to-date on the latest technologies of the time.”

Richard remembers it was his father who taught him how to use computers and how to use software.

Enrico Tedeschi was an Apple fan, and an early adopter of the iPhone since the first iPhone was released in 2007.

A few years after the opening of the Museum of the Radio, Tedeschi went around Italy doing exhibitions with his radios and the books he wrote.

He was very active trying to get Italians more interested in Marconi’s groundbreaking work and in his legacy.

Despite getting lots of attention from local newspapers, Tedeschi did not find enough financial support for his project.

~~~

Enrico Tedeschi in England: Following Marconi’s steps

Disappointed by the lack of understanding of the institutions in his native Italy, Enrico Tedeschi, author of the Guide of The Radio Collector, did not feel enough support in Rome for his Museum of the Radio.

He then decided to move the museum to England where there was an interest in the Italian inventor and electrical engineer Guglielmo Marconi, 1st Marquis of Marconi period compressing the years 1922 to 1929.

Just like Marconi before him, unable to find enough support in his native Italy, Tedeschi made plans to move to Britain determined to make his Radio and Computers Collection exhibition work.

In 1993, Tedeschi closed the Museum of the Radio in Rome, and moved to Brighton, a lovely seaside town in East Sussex, in the south of England.

In England, Enrico believed, people were going to be more receptive to his work and the magic embedded in vintage electronics. He, perhaps, was following Marconi’s steps.

Enrico Tedeschi wrote and self-published The Magic of Sony and The Sinclair Archeology.

Enrico Tedeschi started to receive more artifacts donated by people who wanted to discard their old computers, Marconi radios, calculators, and other electronics. They knew that Tedeschi would be happy adding them to his collection.

The collection started to grow. Tedeschi’s collection grew to over 10,000 artefacts that he kept in his private home, which also became his private museum.

Enrico planned and organized an exhibition devoted to all Sinclair computers in Brighton & Hove, and Sinclair came from London for the opening.

Richard showed me photographs, newspaper articles, even Enrico’s drafts and notes of his books.

Richard said one of Enrico’s favorite items from his collection was the original marble microphone that was used by Mussolini, Winston Churchil, and King George VI. The collection was impressive, indeed.

Bookings to Tedeschi’s private collection was by appointment for individuals and small groups. He personally received and guided the curious visitors, telling them stories about the artefacts, and sharing his knowledge and enthusiasm for the dead media that he so passionately treasured.

Good part of his collection — which he had previously on display in Rome from the mid 1980s to 1993 in his Museum of the Radio — included famous radios from the 1920s, 30s, and 40s; they were radios which had an influence in society and were technologically revolutionary.

Enrico Tedeschi had contacts all over the world and with the Internet, communication became easier for him as well as facilitating research.

Enrico liked to read and collect The Whole Earth Catalog, an American counterculture magazine and product catalog published by Stewart Brand several times a year between 1968 and 1972, and occasionally thereafter, until 1998.

The magazine featured essays and articles, but was primarily focused on product reviews. Enrico Tedeschi was a member of the British Vintage Wireless Society, and he regularly wrote articles for its magazine.

Enrico Tedeschi was a very productive and active man. As an Italian, he loved Italian food so much that he wrote a book about pasta.

To my surprise, the pasta book emerged from a box of technology-related papers, notes, and folders which belonged to Enrico, and that Richard was showing to me.

According to Richard, Enrico used to say: “Italian food is very simple, it’s very quick.” Most Italian dishes are very simple and easy to cook, indeed. “Tasty dishes that are uncomplicated,” added Richard.

~~~

Enrico Tedeschi and Sir Clive Sinclair

Enrico Tedeschi went to Sir Clive Sinclair’s home in London when Sinclair’s company was moving to a new office. There were prototypes made of wood, prototypes of computers that never came out.

There were sketches from electric vehicles that were never produced. Sinclair gave those prototypes and about 20 sketches to Enrico, which became part of Tedeschi’s precious collection.

~~~

The end: Enrico Tedeschi’s collection scattered all over the world

On April 23, 1993, Italian newspaper Il Messaggero announced Enrico Tedeschi’s Radio and Technology Museum was closing in Italy and reopening in England.

“Collecting should not be just amassing the largest possible number of artefacts and memorabilia but also and mainly for the research and understanding of how, when, why, and who invented and produced what, and the social impact and consequences that these products had on the life of millions of people. Collecting should be a way of learning, growing, and self-improvement, and not just a hobby, or an investment.”

- Enrico Tedeschi, (The Magic of Sony)

After Enrico Tedeschi’s death, his son Richard sold everything in his father's collection to other collectors of vintage electronics around the world on eBay.

Richard and his wife were planning on moving out from England. “It was a little bit of our inheritance,” he told me.

Ironically, the collection of the man who once managed to campaign in order to save Guglielmo Marconi’s collection from being scattered around the world ended up having his own collection scattered all over the planet, and his effort and work of over 50 years of his life was forever lost.

~~~

Marconi: London tour and illustrated guidebook

During his years in England, Enrico Tedeschi, radio historian, writer, and collector offered an historical guided tour called ‘Guglielmo Marconi in London.’ He was determined to make people reflect on the social impact that Marconi’s discoveries and work had in humanity.

The tour was a combined underground and walking tour to places that made wireless telegraphy and radio possible. Tedeschi, an expert in Marconi history, guided small groups on Saturday mornings for what I imagine were three unforgettable hours of historical storytelling.

Some of the attractions included the house and hotel where Marconi lived, the places of his early experiments and demonstrations, his first official broadcasting place in London, the beginning of the BBC, and the office that Marconi rented.

For those who were interested but were not able to travel to London, Enrico offered his 40-page illustrated guidebook to help them with a self-guided tour.

~~~

Internet Campaign to save the Marconi collection from auction

Enrico Tedeschi was able to mobilize Guglielmo Marconi’s global enthusiasts through a successful online campaign in which Marconi’s daughter, Princess Elettra Marconi-Giovanelli was also involved. The effort was aimed at saving Guglielmo Marconi’s collection and archive from being scattered all over the world.

The auction was stopped after Enrico Tedeschi — and other equally passionate collectors and defenders of the Marconi Collection and its historical value — mobilized an international crowd of scientists, historians, former employees, and also Marconi’s daughter, Princess Elettra Marconi-Giovanelli through the ‘Save the Marconi Archives Appeal.’

As part of the global effort, Antique Radio Classified (ARC) published on its Website: “Jim Kreuzer, who has the most outstanding Marconi collection in The U. S., has visited the Marconi archives several times over the years. As Jim says, “Access to all these materials in one place — and even more importantly, in the right place historically — is invaluable.”

Now Jim worries that these historic pieces will be scattered all over the world.

“This same sentiment has been expressed on the Internet by British collector Enrico Tedeschi (ARC January 1997) and Willem Hackman, Chairman of the British Vintage Wireless Society, along with many others. They are urging collectors to join the ‘Save the Marconi Archives Appeal.’”

Guglielmo Marconi’s Collection was almost auctioned at British auction house Christie’s South Kensington, in London in 1997. Now, it rests safe in Oxford.

~~~

Guglielmo Marconi’s radio collection and the history of wireless communication valued at £3 million (or almost $4 million), according to The Guardian’s report at the time, was almost scattered worldwide at auction in London in 1997.

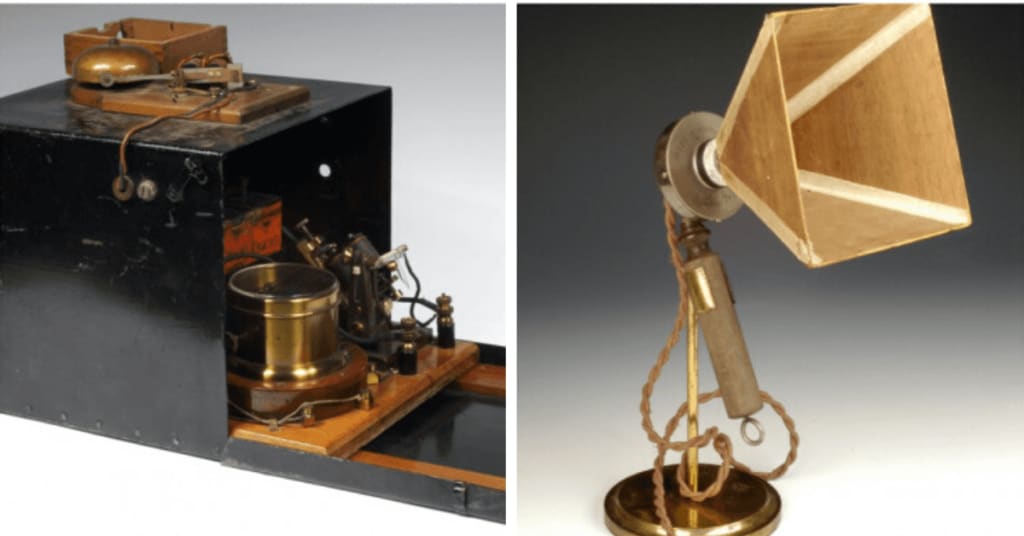

The Collection charts the history of radio from Marconi’s arrival in England in 1896 to the end of World War II.

The two-day sale was expected to bring in over £1 million with estimates ranging from £100 to £20,000 on individual items.

Marconi’s first patents, the 1912 Titanic telegrams, which record warnings of ice and attempts to contact other ships for help, and the microphone used by Dame Nellie Melba to make the first radio broadcast in 1920 would have been forever lost.

Guglielmo Marconi’s invention of wireless telegraphy over 100 years ago marks the beginning of modern wireless telecommunications.

In 1896, Marconi made it possible for a message to pass between two points with the invention of his first patent of improvements in wireless telegraphy — this document was going to be offered in the sale at an estimate of £1,000 to £1,500 at the time.

Other documents and messages of particular interest included those relating to Queen Victoria, as well as a huge number of radio messages transmitted during the sinking of the Titanic.

It was the sinking of the Titanic in 1912 the unfortunate event that finally convinced the world of the importance of the wireless.

The ship, called the ‘unsinkable ship’, had been fitted with Marconi’s most up-to-date wireless technology equipment.

Approximately 2,000 wireless messages known as Marconigrams were sent from the Titanic to and from other ships, including the rescue vessel Carpathia. These historical messages were a major section of the collection up for sale.

Some of Marconi’s earliest recorded wireless messages — with estimates ranging from £500 to £8,000 were also ready to be auctioned — including the Bristol Channel experiments of 1897, the message from the Royal Needles Hotel Station on the Isle of Wight, and the first English Channel transmissions.

In July 1898, the Dublin Express commissioned Marconi to report on the progress of the Kingstown Regatta in Dublin.

Twenty-six of those messages, which represent the first use of wireless to report a sporting or news event, were estimated at £3,000 to £5,000, and were included in the auction.

Even Marconi’s diary from 1901, which included his entry from December of that year, in which he recorded the first signal across the Atlantic, was a highlight of the sale.

This diary was estimated to bring £1,500 to £2,000. And the actual earphone in which Marconi heard this first signal was expected to be sold from £5,000 to £8,000.

Dr. Ambrose Fleming’s letter of November 1904 to Marconi in which he reports for the first time the invention of the valve — “I have not mentioned this to anyone as it may become very useful …” was another fascinating piece of documentation which was expected to be sold from £1,000 to £1,500. This letter was offered alongside a number of Fleming’s early valves.

The Marconi Company was among the first to know about the outbreak of World War I. Working late one August night in 1914, company engineer H.J. Round intercepted a German army communication informing its forces that war had been declared.

That was a day and a half before the official declaration. H.J. Round scribbled the message on the back of a company order form. This historical message was estimated to be auctioned from £2,000 to £3,000.

Four years later, in 1918, the Marconi Company’s London Headquarters also witnessed the end of the war when the Eiffel Tower station transmitted Marshal Foch’s message announcing the Armistice. This document was estimated at £1,000 to £1,500.

By 1920, wireless telephony had developed so far that it was possible to broadcast a program of musical entertainment. It was in November of that year, when famous singer Dame Nellie Melba was persuaded to travel to Essex for the princely sum of £1,000 to broadcast the first program of musical entertainment from one of Marconi’s transmitters at Chelmsford.

The microphone she used had an improvised mouthpiece made from a cigar box which was signed by Dame Melba.

This microphone was expected to be offered at £5,000 to £8,000. From this amateurish beginning of first broadcast, the British Broadcast Corporation (BBC) evolved in 1922, with television following in 1936.

On February 14, 1997, Christie’s South Kensington released the following statement:

“Christie’s South Kensington is awaiting further instructions from [GEC-Marconi] regarding the Marconi Collection, and fully supports the moves being made to keep the Collection intact.”

A joint statement was also released by [GEC-Marconi] and the Science Museum:

“We have had a very constructive discussion, as a result of which we believe that a basis exists for a satisfactory solution between several interested parties which will ensure that the Marconi Collection remains intact in this country. Another statement will be made once further progress has been achieved, when the company would expect to be in a position to withdraw the Collection from public sale.”

The entire collection and archive were then transferred to the University of Oxford, in England.

The artifacts are now on display at the History of Science Museum in Oxford, and all the documents and patents are available to scholars at Bodleian Library.

It was thanks to the tenacity of Enrico Tedeschi, his passion for the history of radio and Marconi’s work, and the success of his Internet project campaign that the Guglielmo Marconi Collection is now safely preserved for future generations, and available for everyone to see.

~~~

About the author: Susan Fourtané is a Science and Technology Journalist, Writer, and Dead Media Archeologist

About the Creator

Susan Fourtané

Susan Fourtané is a Science and Technology Journalist, a professional writer with 18 years experience writing for global media and industry publications. She's a member of the ABSW, WFSJ, Society of Authors, and London Press Club.

Comments (1)

Marconigram, hehehehehe, I really like the sound of that. It sounds like a dish made from macaroni. Jokes aside, I found this whole thing so fascinating! Thank you so much for sharing this!