Does a rationally organised and meaningful world imply an afterlife?

Can the question that Godel tried to answer be addressed in a way that makes sense to contemporary culture?

The world as we know it is set up rationally. Events are organised, and predictable. Their causes and effects are discoverable by humanity, without limitation.

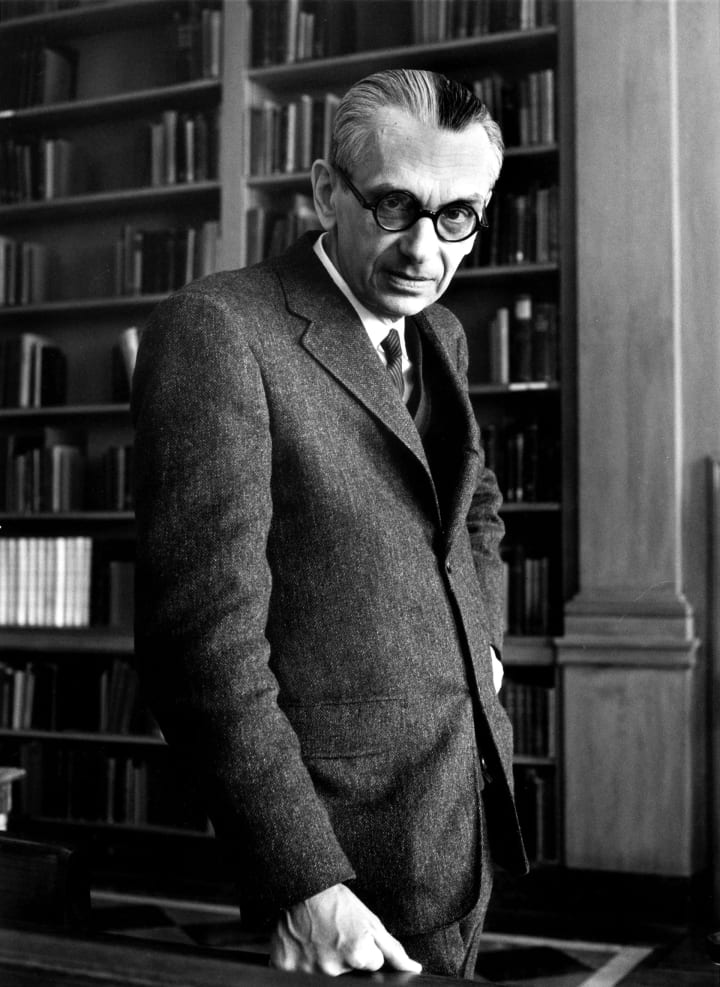

Or at least, so went the thinking of Kurt Gödel, considered one of the greatest logicians of all time, his fame due in large part to the contribution his incompleteness theorems made to the philosophy of mathematics.

Less well known though is Gödel's personal philosophy of life - something that he kept private, perhaps in fear of a negative reaction from other people, as most of us do.

Indeed it is within the private and personal context of his correspondence with his mother that one can most readily access his world views.

His mother, separated from her son by the wide Atlantic ocean, and perhaps despairing that he would ever return home for a visit, asks him whether they shall ever meet again.

In a letter dated 23 July 1961, he responds:

If the world is set up rationally and has a meaning, then that must be so. For what kind of a sense would there be in bringing forth a creature (man), who has such a broad field of possibilities of his own development and of relationships to others, and then not allow him to achieve 1/1000 of it

Posterity has not left a record whether her son's understanding of her question met her expectation. His answer is nonetheless revealing: in a rationally organised and meaningful universe, it would make no sense for a person to exist who has so much potential but due to a finite lifespan achieves so little of it.

In other words, for Gödel, if one assumes that the world makes sense and is meaningful, then it follows that there must be an afterlife.

He felt so strongly about this assumption that he considered it beyond argument:

Does one have a reason to assume that the world is set up rationally? I believe so. For it is certainly not chaotic and arbitrary, but rather, as science shows, the greatest regularity and order reign in everything. Order is, however, a form of rationality. How is another life to be imagined?

For him, indeed, the very orderliness of the universe appears to have been his bulwark against the ravening maw that is chaos and arbitrariness - and with it his personal proof of the afterlife.

I cannot help feeling however that his argument might have made much more sense in the vanished world of the 1960s elder intelligentsia than it does now.

In a world regularly beset by random and arbitrary crises, Gödel's personal thoughts seem to ring hollow. To those threatened by war, pandemic, and climate change; or the more mundane losses, crimes and personal calamities, there isn't much if any comfort to be drawn from a universal order.

It all seems to ring hollow.

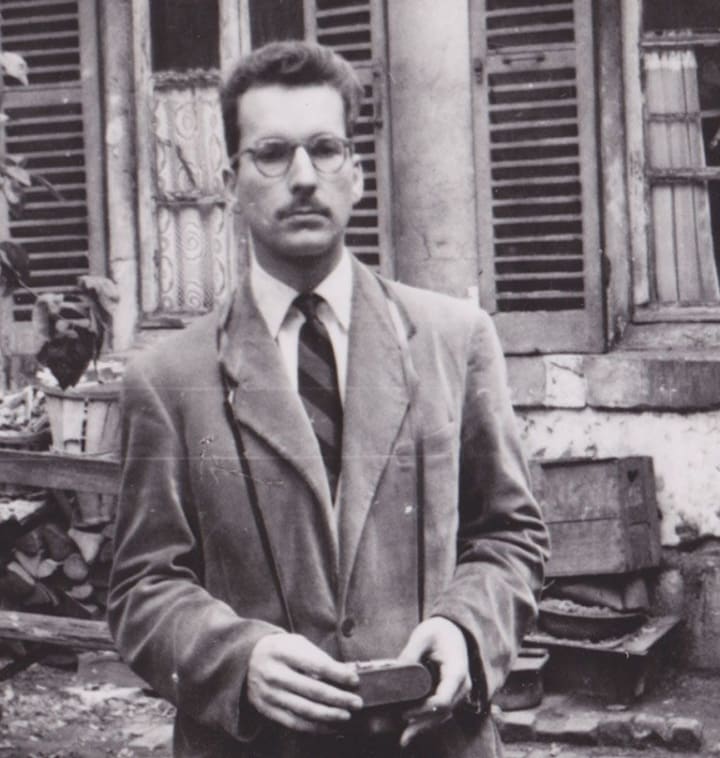

Few people could put their finger on this contemporary malaise better than his near contemporary, Dr. Ernest Becker - who, indeed, did not live as long as him.

Within the pages of Becker's best-known work "The Denial of Death" we find, painted in vivid colours, the culmination of the very opposite picture to that which Gödel tried to portray:

This is the terror: to have emerged from nothing, to have a name, consciousness of self, deep inner feelings, an excruciating inner yearning for life and self-expression – and with all this yet to die.

Gödel's meaning of 'sense' applied to the world is turned on it's head - there is no sense or meaning, and we will all be annihilated. For Becker, this is the terror that we seek to escape, to deny.

So awful is the vision Becker paints that to him the development of character as we grow up into adults serves as 'cultural armour' against the clamouring maw of chaos and disorder that Gödel feared:

It can’t be overstressed … that to see the world as it really is is devastating and terrifying. It achieves the very result that the child has painfully built his character over the years in order to avoid: it makes routine, automatic, secure self-confident activity impossible.

What he called 'psychotic breaks' arise when the defensive instruments we have built are no longer effective, perhaps because they have been curtailed, or because of other events in a person's life or their wider world. The recent COVID-19 pandemic is surely a case in point: what better illustration of an apparently arbitrary world that affected so many people can we find in the past few years?

Indeed, for those of us for whom it seems the meaningless and purposelessness of reality is as apparent and clear as the light of the noon-day sun ...

When you get a person to look at the sun as it bakes down on the daily carnage taking place on earth, the ridiculous accidents, the utter fragility of life, the powerlessness of those he thought most powerful – what comfort can you give him from a psychotherapeutic point of view

For us, living in the world of today, Gödel's ordered world - and therefore the expectation of an afterlife - crumbles to rubble and dust under the unbearable weight of the 'world-as-it-is'.

Indeed, Gödel's rationality and regularity seems little more than a cruel jest to those of us weighed down under the impossible burdens of annihilation angst.

In what way, then, can the expectation that Gödel was striving to address be re-framed for modern audiences?

Perhaps one may begin with a little humility.

The feeling of not knowing, the freedom from the expectation of having to know, can be liberating.

Perhaps the world that we live in isn't intelligible; perhaps all its secrets cannot be laid bare to humanity's investigative powers, to the bright light of science.

Perhaps we are insufficient to the task, by virtue of the limits to our innate capabilities.

That, for me, is a gently suggestive first step. A step that, similar to walking on springy turf, gently encourages one forwards.

Maybe, a desire for there to be a fully intelligible universe is wishful thinking.

I think, as maybe the poet Blake did, that a dandelion clock is an apt metaphor for our quest for the afterlife. His "Auguries of Innocence" starts:

To see a World in a Grain of Sand // And a Heaven in a Wild Flower

and finds its coda with

Under every grief & pine // Runs a joy with silken twine

For Blake then, it is through contemplation of the world as it is, not with the eyes of devouring, of lustful appetites for the knowledge that we might extract, but with the eyes of wonder, of innocence, that his 'joy' may be found.

The peerless divine philosopher ʻAbdu'l-Bahá, son of the founder of the Baha'i Faith linked things of the world that are immediately apparent with those that are mostly hidden from view in this paragraph:

[E]arthly and heavenly, material and spiritual, accidental and essential, particular and universal, structure and foundation, appearance and reality and the essence of all things, both inward and outward -- all of these are connected one with another and are interrelated in such a manner that you will find that drops are patterned after seas, and that atoms are structured after suns in proportion to their capacities and potentialities.

Perhaps speaking to Gödel's yearning for an intelligible universe in the face of the darkness of superstition, he continues:

... it is by applying the outward world to the inner, the high to the low, the small to the large, the general to the particular that, with abundant clearness, it becometh apparent that the new rules arrived at by the science of astronomy are in closer accord with the universal divine principles than the other erroneous theories and propositions.

What does ʻAbdu'l-Bahá say about these 'universal divine principles'?

Love is the most great law that ruleth this mighty and heavenly cycle, the unique power that bindeth together the divers elements of this material world, the supreme magnetic force that directeth the movements of the spheres in the celestial realms. Love revealeth with unfailing and limitless power the mysteries latent in the universe.

I think that perhaps what Gödel sought can be found in what we don't - and perhaps cannot - know, rather than appealing to notions of order in what little we can discover.

I'd suggest what is to me the most appropriate example of a phenomenon of the unknown or unknowable that we can all relate to in some way or other is what some call the 'near-death experience'.

A thematic analysis of published anonymous accounts set to a common format reveals the following they have in common ...

Their authors one and all have to overcome a necessary ineffability from lacking shared points of reference, barriers to sharing from perceived societal resistance, and built-in biases arising from their own cultural and societal backgrounds.

However, once these obstacles are overcome, the themes these accounts address are:

- oneness, interconnection and unity

- unlimited knowledge that often cannot be expressed

- an almost complete lack of the fear of death

- and finally, most powerfully, the kind of unconditional love that not only sweeps us off our feet but also constitutes the very bedrock of existence:

Instead of restricting the mysteries of love to psychological or philosophical studies, science will someday discover the all-powerful force of love and measure it as they now do electricity, gravity and geo-thermal forces. When science discovers the forces of love and learns how to release it from the bars of the ego, they will have the answer to every question and ill that has plagued mankind.

For me, it is the development of a visceral understanding - in thought, and in practice - of that unconditional love, interconnectedness and the process of overcoming our fear of death that is at the very heart of motivating us to take on the challenges that lay in front of us as humanity.

Perhaps, after all, confidence in the afterlife can be found not by appealing to a rigidly constrained clockwork universe, but one for which we admit our insufficiency in front of the power of Divine Love.

Maybe, an irony in Gödel's quest is that the 'order' he seeks can be found in the 'most great law' that is Unconditional Love?

About the Creator

Andrew Scott

Student scribbler

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.