Chasing Flavors Across the Globe

Traveling with Anosmia and Parosmia

In 2012, a summer viral infection caused damage to my olfactory nerve. I was unable to smell, a condition called anosmia. At first, I thought I was just still congested and within a week or two, I’d regain my sense of smell. But when we went to a family member’s wedding a few weeks out and I could neither detect the scent of the beautiful flowers at the venue or the flavors of the special celebration meal I knew something was wrong. Then came something called parosmia, which was a distorted sense of smell and flavors. The air smelled foul, and I wasn’t able to sleep breathing in the odors of what seemed like being in a dumpster full of garbage. Things like wine, citrus fruits, melons and cucumbers tasted like what I would imagine eating a dirty diaper is like. Everything else I couldn’t smell.

We love Maine, in part, for its soft-shell lobster and clams, eaten waterside outdoors at a lobster pound where the trawlers brought them freshly caught. The salty sea air, sound of the waves gently lapping, the flavors of the seafood dripping in melted butter, a bottle of wine to wash down the food, the scent of the seafood lingering on my hands even when I wash them in the outdoor utility sink, as the sun slowly sets over the ocean; this is the perfect meal and setting for me. This was a regular vacation spot for our family, but when we went there that year, only the sounds and sight were available for me.

I sought medical treatment from a regional smell and taste disorder center. My sense of taste was intact; this is what the taste buds in the mouth can detect – salty, sweet, sour, bitter and umami. However, smell and taste go hand in hand to make flavor. So, without the ability to smell, I could not tell in blind tests the difference between various foods that previously I had been able to discern from just a whiff. There was little the center could offer – the use of steroidal nasal sprays and sniffing strong fragrance candles and essential oils to awaken or retrain my brain. I was told to get mixed bags of Jelly Belly beans and try to taste the different flavors. There was no clear prognosis for being able to smell, perhaps it would return little by little or perhaps not. It has only been since COVID19, when anosmia became a condition that many long haulers have experienced, that there is an effort in research on this loss of sense.

My enjoyment, post anosmia onset, was in eating was only in the visual appearance of the food and contrasts of textures – crisp tortilla chips dipped in silky guacamole, crunchy nuts in a chewy granola bar. I lost weight and became depressed. I avoided all things that had a sour taste, which translated into something inedible for me when I tried them (like wine, lemon, vinegar and even tomatoes).

I was told by my ENT that at least I wasn’t like one of his other patients, a professional chef. But even though I didn’t cook professionally, cooking and baking had been a central part of my life. Sharing meals with others was not only the chance to enjoy their company but also, when I make the food, it is my way of showing my love and gratitude for them.

By high school, I was replicating the dishes that Graham Kerr, aka The Galloping Gourmet presented on his television show. I loved the rich flavors of his recipes, the challenge of making puff pastry for napoleons and beef wellingtons or croquembouche, the cream puff tower with caramelized spun sugar from scratch. I had pleasure in helping my parents prepare for dinner parties where we served these dishes.

As an American of Filipino heritage, I also loved learning to make the classics from the Philippines, taught by my grandmother, a home economics professor, my mother and aunties. When my grandparents would visit, my grandfather would pick tender lettuce leaves from our garden. Meanwhile we made paper thin crepe like wrappers for fresh Lumpia into which we would tuck the lettuce and a filling of pork, shrimp, green beans, bean sprouts, cabbage and carrots before rolling up the wrapper. A similar filling would be made for fried lumpia, using spring roll wrappers and fried; this was our version of a Chinese egg roll. There was pansit - rice (bihon), wheat (canton) or bean thread noodles mixed with vegetables such snow peas, carrots and cabbage and pork, chicken or shrimp. The Philippines was influenced through trade with China and was a Spanish colony. When Spain lost the Spanish American war, the Philippines became a territory of the United States, and was occupied by the Japanese during WWII. It didn’t become a sovereign country until 1946. As such, the culture and the foods have a mix of both Asian and Western cultures, and most people speak English. Leche flan is a caramel custard. Lechon, spit roasted suckling pig, is found at all celebrations along with a host of traditional accoutrements. If there was one national dish that the Philippines is known for it would adobo. Adobo is made from chicken and/or pork cooked in a garlicky mix of soy sauce and vinegar; the sauce spooned over rice with the meat. The vinegar helped preserve the meat prior to refrigeration.

And of course, there were the American foods: homemade cinnamon raisin bread, chocolate chip cookies, pot roast, chicken ala king and Jell-O with every addition one could imagine. I grew up in Rochester, NY which was the home of Ragu brand sauce. I loved my pasta in meat sauce so much that I was nicknamed Bethy Spaghetti. My first cookbook was Betty Crocker’s cookbook for boys and girls, and I tried every recipe in that book.

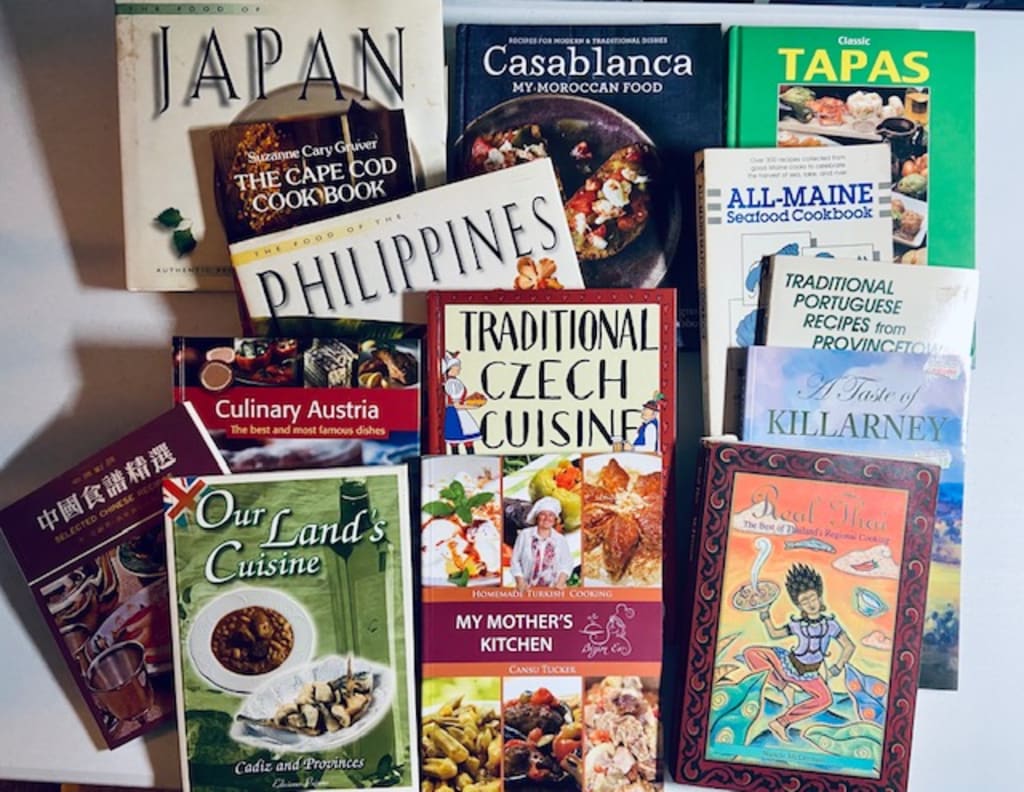

I have always had a love for and curiosity about all the different cultures in the world. Traveling and exploring cuisines from diverse ethnicities fed that passion. If the field of study called food sociology had been an option when I was young, I may have chosen that path. Instead, I studied psychology and then got a Master of Social Work. Even when I wasn’t able to actually visit a country, learning about those cuisines gave me a window into part of that culture. I collected and was gifted cookbooks from various regions and countries, reading them and trying the recipes. When meeting someone from another place, I enjoyed asking them about the foods of their heritage. I found it was often a great ice breaker into learning more about them and their culture. It was also usually a safe topic to discuss with most people, unless one is with a group of relatives who all claim to have the best version of a specific dish.

As a social worker, I’ve had the honor and pleasure of having both colleagues and service recipients who were from every cultural background in the world. My professional ability to work with them was enhance when I had a better understanding of their culture. Rapport is more easily established with a patient when the clinician has even a bit of understanding of their cultural heritage. Making cultural connections helped me to determine what factors were influential in those people’s lives and better assist them. For example, being aware of religious holidays helped the scheduling of meetings or appointments. Some people have cultural restrictions which affect the reasons for their behavior; knowledge of this allowed me to be respectful of these boundaries and understand issues within that framework.

Thus, traveling both in the United States and other countries allows me to experience those other cultures, which benefited me both personally and professionally. Having the chance to taste those authentically made dishes I read about made the memories of that place more special. My travel souvenirs were cookbooks from the places I visited so I could replicate at home the dishes I tried abroad. Each recipe evoked a memory of that place and the people I met on my trip. There were the square slices of pizza el taglio in Florence which was so different than the square bready slices they served in the school cafeteria. I remember my first taste of roasted beets and green beans pickled in dill in a charcuterie and butter croissants in Paris, bitter orange marmalade and tortilla Espanol in Seville. And there was shoofly pie and thick cut homemade noodles and chicken in Pennsylvania’s Amish country, and Cioppino seafood stew and sourdough bread from San Francisco.

Twelve years ago, I began almost yearly travels with a group of friends. Each year we would choose a city to visit for the following year. We would not only plan out the attractions to visit, but often look at must visit eateries, such as a restaurant famous for its Bolognese sauce in Rome, or the best bangers and mash in Galloway Ireland.

We travelled to Barcelona in 2013, a year after the anosmia onset. By then, I had learned to cope with the parosmia “smells”, and the anosmia. I remember the paella we had at the seaside restaurant, with a wide variety of seafood arranged in the paella pan because it was beautiful and enjoyed the contrast of the rice and the tender chewiness of the fish and seafood. I assumed it was delicious because every bit was devoured. And the fried potatoes tapas were crunchy and salty. La Boquería, the famous marketplace in Barcelona, would have previously been one of my favorite ‘foodie’ places to explore, but while it was fun to see, I had no interest in lingering.

A few months later I found myself traveling with my dad to Hawaii for a family member’s funeral. I was yet again in a place that was famous for, not only for its beauty and beaches, but also for its cuisine. We had lechon, fresh lumpia, pansit and the rest of the Filipino Lechonada typical sides after the service. There was wild tiny papaya that relatives picked while hiking along a mountain ridge. I helped rinse them but was repulsed as a result of the way my brain read its flavor profile when I tasted it. The only fruit there that didn’t bother me with phantom stinky flavor was mango. As a person who had formerly adored all tropical fruits, I was no longer able to tolerate them. When I was growing up, my aunt would mail a pineapple macadamia fruit cake; it was my favorite birthday cake, but I no longer had interest in buying some to take home. I found myself tasting small bites of foods that people had brought over for our mourning family in order to be polite but not wanting to explain why I wasn’t enjoying the food.

The anosmia and parosmia persisted. I developed coping strategies to handle everyday life. We jokingly called it my “smellavision condition”. I continued to be the primary cook for my family. I tried to provide them with the well-seasoned foods they were accustomed to, and but relied upon them to taste each dish to make sure the food was palatable to them. A tasting spoon was placed next to the stove for the family member I could wrangle into the kitchen to do the tasting. I set timers for less than the suggested cooking time by a few minutes in order to prevent burning the dish. My eyes became my way of knowing if something was done. A carbon monoxide detector was installed; we have a gas range.

Prior to the anosmia I frequently would do my own riff on a recipe, tasting it to make sure the flavors worked. I loved sharing what I made with others, and I was known for the things I would cook or bake for gatherings. Now, I stuck to my classic standards recipes that I had prepared for decades. If I wanted to try something new, I searched for recipes on the internet with lots of positive reviews. I read every review to make sure to incorporate any frequently suggested tweaks (such as needing more salt, baking for less time, etc.). Food attributes that are typically secondary to the flavors became important. I prepared dishes with high contrast textures and mouth feel. Plating and appearance also were focal.

I continued to enjoy making foods for others. Since I had little interest in eating the foods, my husband’s and my work colleagues became used to their Monday morning treats that I baked over the weekends. Like Beethoven who continued to compose music after he lost his hearing, the memory of food flavors propelled me to continue cooking. I loved making something that figuratively and literally nourished my family and friends and the gathering of loved ones. I was determined not to let the anosmia keep me from doing that.

Two years after the onset of my anosmia, I traveled with the gals to Venice. I suppose the silver lining was that I heard the canal water can be somewhat stinky, and since I couldn’t smell, it made no difference to me. I remember a cuttlefish meal on Murano Island, dark chewy but tender seafood served with ribbons of fresh pasta, the hearty squares of pizza, and the cool sweetness of gelati but couldn’t tell you what they tasted like.

In three years’ time, I began to slowly recover some of sense of smell. I remember the first time waking up and coming downstairs to the smell of the coffee my husband brewed. White wine was palatable but to this day, I still have the phantom parosmia for cucumbers, citrus and melons. Stronger scents like cinnamon and mint were finally detectable.

That year we traveled to Turkey, and although my sense of smell had only returned to about 50%, it felt like a rebirth. There was gozleme, a flat bread filled with spinach and feta we ate in Ephesus, water borek with cheese for breakfast (a phyllo like dough that is boiled and layered like a lasagna). Kofte meatballs were served grilled or with vegetables in a stew like dish. And the baklava, my oh my, the crisp layers of phyllo and nuts bathed in a sweet syrup. For someone with reduced smell, just those properties alone made it the perfect treat with its loads of texture contrast and sweetness. In Istanbul, we went to the spice bazaar. I bought spice mixes for different kinds of koftes, bay leaves, saffron, teas, so much so that one of the guys in the group helped carry them back to the hotel. We went to a restaurant where the owner sold her own cookbook in English and signed my copy.

When I returned home, I made many of the recipes from that cookbook and online sites using the spices I brought back. The women in Turkey used a thin rolling pin, the diameter of a broomstick and a yard long, to roll out the gozleme and dough for the water borek, deftly wrapping the growing round of dough around the pin then, spinning the dough out as it’s re-rolled until it is paper thin and as wide as the rolling pin is long. I wasn’t able to find a local source of the Turkish Yufka, the filo dough that can be purchased for the water borek, also known as su-boregi, but tried different online recipes with moderate success. I made my own makeshift pin out of a dowel. Even though I watched YouTube videos repeatedly, I did not have the coordination or skill to even come close to rolling the dough out that thinly. How they managed to do this, fill them and cook without tearing still amazes me.

As the years passed, my ability to smell grew bit by bit. Our trip to Hungary, Vienna, Prague, Berlin and Slovakia gave me more recipes to try to replicate. I brought back bags of paprika which must have raised alarm with airport security since my luggage was opened and inspected (I guess half kilo bags of powder looked suspicious). I made chicken paprikash, like the one we had on a cruise of the Blue Danube. There was the sacher torte from Vienna and the Slovakian potato dumplings with cheese called Halusky to make. However, the Trdelník pastry rolls that can be filled with ice cream are perhaps a pastry best left for the professionals who make them in Prague.

In 2019 we travelled to Morocco. My sense of smell had healed to about 80% of what it was before. By then, I had integrated many of my adaptive techniques for cooking without being able to smell but was finally able to season foods without requiring an additional taste tester. I remember reading in a cooking magazine decades ago that couscous was prepared by hand, women who could roll the tiny pellets were desirable wives. Most of the Moroccans I spoke to no longer make it from scratch. So, I jumped at the opportunity to attend a live demonstration of by a young woman who was carrying on that tradition. She showed us how after rolling those grains in a special grooved bowl, they would be steamed in a special double layer pan called a couscoussier. A fragrant stew would be cooked at the bottom and the couscous on top, allowing it to capture the wonderful flavors of the stew.

We enjoyed different tagines which were meats and vegetables stewed in a clay pot, and all kinds of flat breads and vegetable dishes. The market vendors had spices and spice mixes that were displayed in high peaks, sometimes layered so you could see the discreet spices before you bought their version. The most famous mix is called Ras el hanout which can include up to aromatic 80 different spices such as cinnamon, cardamon, ginger and turmeric that would bring a complex flavor to the dishes. Like the spice mixes of India and chili con carne, each family had their own version.

Travel plans for Vietnam and Cambodia have been postponed due to the pandemic. But the traveling gals are planning a trip stateside to New Orleans. I can’t wait to get back on the road and feed my passion for learning about yet another place, famous for its jazz, Cajun and Creole traditions and food. Even if my ability to smell is not fully regained, there’ll still be plenty to savor in the cuisine, the sights and the culture.

I’ve provided tips for others who are dealing with anosmia throughout, but here are some takeaways:

1) Like people who lose their other senses, you may find yourself grieving over this loss. This is normal, and thankfully there have been many online support groups that have started up in the past year or so. AbScent is one such support, with a special group for people who group for people dealing with COVID-19 anosmia AbScent | Anosmia support | Facebook. There is a wider variety of medical treatment available, than when I was diagnosed, that people are finding beneficial.

2) Put your focus on what is available for you to enjoy – as I mentioned before, I looked for dishes that had textural contrast and visual appeal to encourage my desire to eat. When traveling, enjoy the sights, the people and the culture – use your other senses!

3) Look for adaptive techniques that help you to live and eat safely. Since I could not tell if milk was spoiled, I switched to using nut milks which had a longer life. I also bought the 8oz cartons of shelf stable milk, when in doubt I felt better about tossing a half cup of milk over a gallon.

4) Cucumbers, bananas and citrus still have that stinky odor for me, and I still can’t smell burning foods well. Even when a salad has the cucumbers removed, I can taste it in the rest of the salad. I no longer drink lemonade, but lemon juice in small amounts mixed with other ingredients is okay. When preparing foods, I look for recipes where the star ingredient isn’t citrus. My husband eats bananas daily, and while I don’t care for the smell, it’s his home too. I’ve had to move to my seat when someone at a working lunch meeting eats her juicy orange next to me, or literally step out to take a breather. Be flexible when around others and ask that they are also willing to compromise.

I’ve included links to recipes for the foods around the world that I’ve prepared and shown in photos throughout this piece. But, if I had one favorite recipe to share, it would be Filipino chicken adobo. Its name is Spanish, which means a combination of sour taste (either citrus or vinegar) and garlic to flavor food, but the preparation with soy sauce originates from our Asian influenced heritage. It’s simple to prepare, with ingredients that many people have in their pantry. And while it could be seen as the Filipino national dish, there are as many versions as there are Filipinos. My extended family has at least half a dozen.

Filipino Chicken Adobo, my mother’s version:

1 whole chicken, cut in pieces or 4-5 lbs. chicken thighs (dark meat works best)

½ cup vinegar – white vinegar, cider vinegar or palm/cane vinegar

½ cup soy sauce

4-6 garlic cloves, minced

1 bay leaf

2 tablespoons brown sugar

1 teaspoon black peppercorns (or ¾ teaspoon ground black pepper)

Optional – 2 tablespoons of scallions, green part, thinly sliced for garnish.

1. Optional first step: Mix all ingredients and marinate for 1-3 hours.

2. If skipping first step, place all ingredients in a large pot or dutch oven. Don’t use aluminum or cast iron pot as vinegar can ruin those pots. Braising liquid will not cover chicken, and only come up to about 1/3 to ½ way up. ½ cup water can be added if braising liquid is covers less than 1/3 of the chicken.

3. Bring braising liquid to a boil, cover, then turn down to simmer. After 30 minutes, uncover and continue to simmer for 10-20 minutes until chicken is cooked through and tender. It will smell somewhat pungent from the vinegar, but will not taste sour when done.

4. Remove chicken. There will be about a cup or so of the braising liquid. If there’s more sauce than that, bring sauce to a fast boil and reduce.

5. Taste the sauce for seasoning, may add a tablespoon more of sugar, or some salt and pepper.

6. If the sauce is oily, pour off most of the fat. Alternatively let it cool with the chicken and refrigerate. The fat will solidify on top and be easily removed. Adobo is a dish that is just as good or even better when served the next day.

7. Serve chicken and sauce, garnish with sliced scallions over white rice. Sarap! (Filipino for delicious)

Variations on the same theme:

- Use only chicken wings and bake in oven at 350 degrees until done to serve as an appetizer. Sauce will be reduced to make a glaze.

- Add half a can or more of coconut milk (not the coconut beverage from a carton served as dairy substitute or sweetened coconut cream used for drinks like pina coladas) to the braising liquid.

- Pork adobo is made similarly, using cubed pork belly or boneless “country style ribs”. Look for pork that is not lean; the fat helps keep it tender. Brown the pork in 1 tablespoon of vegetable oil, then add braising liquid. Simmer until tender, 1-2 hours.

- If doing a combination of pork and chicken, cook the pork first for 40 minutes, then add the chicken.

- The addition of more sugar or even a can of cola makes the flavor more like a teriyaki level of sweetness.

Recipe links for all other dishes:

https://cooking.nytimes.com/recipes/1018068-chicken-paprikash

https://www.giverecipe.com/boiled-borek/

https://ozlemsturkishtable.com/2010/06/casserole-of-meatballs-potatoes-tomatoes-and-peppers-izmir-kofte-my-way/

http://www.mymoroccanfood.com/home/2015/4/23/7-moroccan-seven-vegetables-couscous?rq=7%20vegetables

https://www.bakinglikeachef.com/meringue-dessert-merveilleux-pierre-marcolini/

About the Creator

Beth Imperial-Rogers

Social worker, teacher, maker of all sorts

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.