Family on Fire: The Secrets of the Father

Often in the son I see the uncovered secrets of the father. (F. Nietzsche) A man knows he is growing old because he begins to look like his father. (Gabriel Garcia Marquez)

1. The Parable of the Machines

I n 5 years I will have lived longer than my father. It’s the natural order – generations surpass each other.

My supercharged math brain builds ratios for everything, but the main ratio has always been the staggered numerical parallel with my father: I recall thinking, this is me at 28, what was he doing at 28, when I was four? He worked on Wall Street and taught me to read. I went to pre-school a fluent reader; I had to prove to adults I hadn’t memorized Peter Pan. That began my conflicted relationship with the doubting adult world.

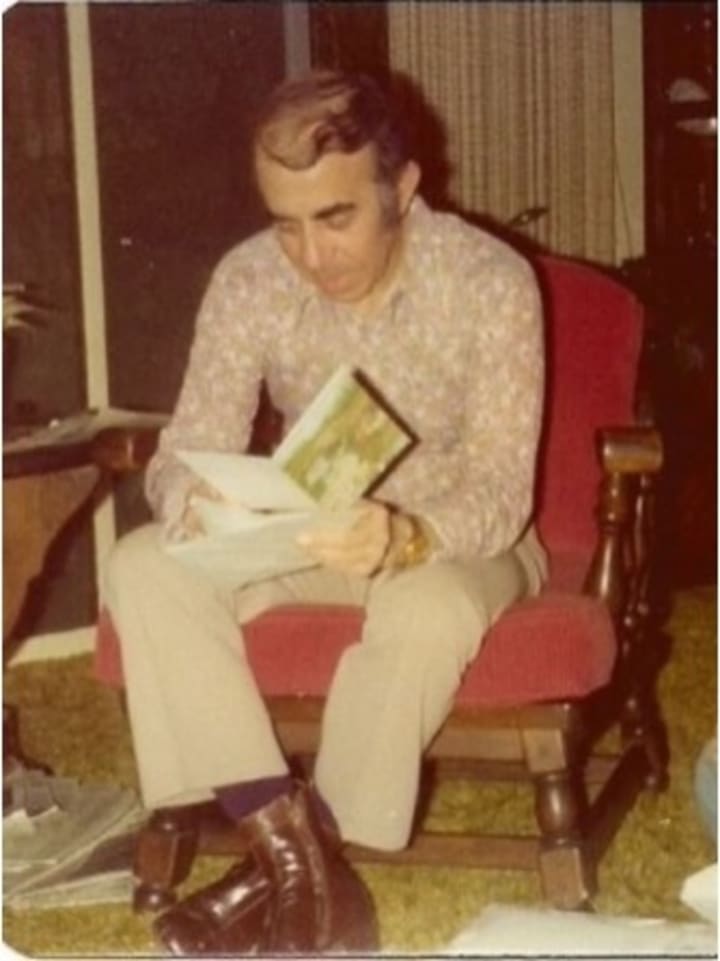

My father was the youngest of four children, nine years younger than his closest sibling. He was considered the family scholar, but only spent a few months in college. Named Harold at birth, for his entire life he was known as Sonny. ‘There were so many people in our household speaking so many different languages,’ his sister Isabel reports, ‘they just called him Sonny.’ That explained my father’s interesting relationship with names and nationalities.

His father and brother were plumbers: strong, wordless men whose backs were their main asset. It would be difficult to find anyone having less aptitude for mechanics than Sonny. Whatever he bought was non-functioning within weeks. Still, he insisted that anything could be fixed - 'It's a machine,' he would say of a malfunctioning TV set or electric grill, 'man vs machine, man wins.' But then in a rage he would throw a useless toaster against a wall, sending us a clear message:

Anything can be fixed. Just not by us.

2. Creating Lives

The Masters Degree I had earned at age 28 morphed into a PhD. when he was trying to impress people. He trusted me to make up an esoteric dissertation so no one would probe. I was a thinker; I had many theories I could use for this intellectual shell game. The one time someone asked about the dissertation title “Power Geometry” I told them, 'You and I are standing here along a diagonal, with others around us in their own spatial relationship with our vector. Follow the current. Who has the power? Where is the power? If you have it, how do I get it?' His girlfriend pulled him away quickly.

At 18 he cast me as a financial prodigy, paid me $25 an hour to summarize the transcript of a disciplinary hearing he and a stock broker cohort had just been through. They were being investigated for underreporting international income. I suspected my father had led them down this path and needed something spectacular to redeem himself, so I was advertised as having a 167 I.Q. and accepted at Berkeley to study Economics. He played up my synesthesia (a condition where the senses blend; I associated numbers and letters with specific colors) as a mystical gift to the financial world.

I made a presentation at the sprawling house leased by their leader. Pre-Euro, the French, Belgian and Swiss francs were different currencies and they had confused the exchange rates. The amount of underreporting would have been roughly equal to mistakenly using the French conversion rate on the Swiss transactions. In Argentina, a political upheaval clouded any financial narrative; it was impossible to know what had occurred. ‘That’s the story then,’ their leader said forcefully, jumping up in his excitement. ‘And we’re sticking to it!’ My father told me later: ‘Your best performance.’

A group of four were suspended from trading for a year for mid-level compliance violations. The mistaken conversion explanation was accepted: no financial penalties were handed down.

I joined the Air Force when I was 20, and shortly after discharge, on our way into a party, my father gripped my arm and told me, with some urgency: ‘They think you're a fighter pilot. If it comes up, tell them it's confidential.' I was only a half-year removed from a year’s tour in Iceland where I watched the skies at the northeastern edge of NATO airspace, so I knew the lingo – but fighter pilots were hallowed ground.

I could feel the eyes of the partygoers on me when they thought I wasn’t looking. What else had Sonny said? I was on the apartment’s tiny balcony when an emergency room doctor with long stringy hair, stethoscope dangling, smoking a crushed European cigarette that he held between his thumb and forefinger, moved next to me; we could have been in a phone booth.

'Your father,' he whispered in an accent I couldn't place, 'constantly sings you.' He paused, repeated sings you, like I was an actor needing to hear my cue again. He asked, 'Did you really .......?' and now he was clearly invested in my response, his eyes, despite his attempts at cool Euro detachment, almost begged me to answer. He leaned over the railing and looked back at me from a great and perilous distance. 'Really?' he reinforced with a raised eyebrow, and I kept our eyes locked and said, 'I did. Really.' He seemed to relax. 'Thank you .......' the man said, nodding, 'for your .........well, you know.' I didn’t, but shook his hand for closure.

‘He’s Irish. IRA. No one else knows. The Czech accent is a ruse,’ my father told me on the way home, then added: ‘He ties a helluva tourniquet.’

We always had Irish paraphernalia around: calendars, leprechaun figurines, a book of Dylan Thomas poems. When I was 8 mail came for a Harold Shawn Halloran, decorated with a HSH monogram. My sister brought it to me. ‘You can go to jail if you have mail that’s not yours,’ she cautioned.

I understood: Whoever we were, it may not be enough. We had a right to our share of the world’s riches, and if that was a problem we created the story and slipped in through a different door. Ambition wasn’t restricted by reality; in this movie we had license to create. It was as if through Sonny's imagination I was living my fullest life. I was never going to be a fighter pilot, but for that one evening I could approach its essence.

Taking on these accomplished roles was the equivalent of a credit card: was it a lie every time you paid by platinum Amex because you didn't have cash? It was an extension of capability, making us larger, limitless. There was a darker side in playing out a story that wasn’t mine; a corrosive guilt ate away at parts of me.

But I could work my way into those accomplishments, grow into the lie until it was true, until I was true. Then I would see my father through that lens and be hit with a jolt of shame, and fear for my future. Sonny had never grown into his various roles: he was not the wise investor, the confidante of celebrities, the deal-making movie producer, the devout intellectual Catholic, the mystery man protecting IRA operatives. He had the trappings, for brief interludes (some of it financed through my good credit, unknown to me) -- but on the road to actually being these men, invariably he fell into sinkholes, or had to change course when faced with a requirement he couldn’t meet, or come up with funds he didn’t have, and so the big opportunities were denied him, and he had to scramble around in their wake, trying to get pieces to fit, but they never did.

Years later, when I was recounting this to a woman whose perspective I valued, she listened with great interest before telling me: It's life as theater. He was an artist.

3. Families on Fire

Tell that to my mother. She believed she had married a stock broker, not a character actor.

In 1977, I was 22, a year into my Air Force tour when things went haywire. I was getting married to save a rocky relationship; the bride was at the age when girls in her family had their wedding; my relevance didn't extend beyond standing on the piece of tape that read: GROOM. The morning of the wedding, we were doing a station-to-station run-through, and a pushy event specialist ordered me to stand at my place. I did, and looked down to see my feet were positioned in such a way that the letters read: DOOM.

The day before I had threatened to call the whole thing off. The bride was treating me like an unwanted appendage, and I resented the pressure and especially the style of the large wedding. I had warned them – something smaller would give us room to maneuver if we needed it. Now we had scores of relatives flying in from all over the country and were locked into what the mothers wanted and a little girl's dream that had nothing to do with me. They had said a compromise was possible but that was forgotten after the first phone call with the insufferable wedding specialist; what she wanted was more important than my wishes. No compromises for her resumé.

We were in my mother's hotel room. 'Somebody better tell that bossy bitch to cut the Cruella De Ville act or I'll call it off based on her crap alone,' I raged, ‘and don’t get me started on how you’re treating me,’ I directed at the bride. I could see my mother knew this was a bit more serious than just talking me down from cold feet, and that my earlier warning, having gone unheeded, was the potential source of a lifetime’s legitimate resentment and blame. In the bride's eyes was the fear that she would be responsible if I did the unthinkable. But my mother settled me down; the show went on.

Early on wedding day, waiting in line at a café, a Dalmatian sunk his teeth into my thigh. The dog turned its mean eyes on me as I stood talking to someone, bared its teeth, growled and launched. I backed into the people behind me with the dog on my leg; someone screamed, a woman fell; my friend finally pulled the dog off me. The owner leashed it and disappeared. 'What did you do?' the café proprietor asked me. ‘That dog never acts like that.'

I shrugged. Bad juju was flying off me at a frequency the canine must have felt intensely. Maybe my guardian angel was trying to put me in the hospital to halt the wedding. Two spots of blood soaked through my jeans: sharp front teeth had punctured my skin. The owner faxed the dog's vaccinations to the restaurant at their request; its rabies shot was current. Following breakfast, we went to the venue for our final orders. Afterward everyone had plans but me. It was 10:30am; the wedding was at 2pm. A bridesmaid dropped me at the oceanfront hotel.

I called my father, left a message. No arrangements had been made to pick me up to take me to the wedding. I hadn't brought my car, and here I was, stranded. I would be checking out soon, so I began packing. If one more thing went wrong, I would bolt. There was an outside chance they would forget about me. My report time was at 1:30pm; I'd give them until 1:15, and if no one showed up I would take a cab to the airport. I called Aeromexico -- a 4:35 flight to Cabo had rows of seats available.

I told the concierge to have a 1:15 taxi on standby. I hoped that I would be forgotten. I watched TV, growing edgier by the minute. The bite wounds throbbed.

I strolled the hotel property, and ran into a friend of my father’s from his youth. ‘Just got here,’ he explained. ‘Friggin’ La Guardia, it’s a nightmare, you gotta fly JFK. Got any pictures of Sonny? Haven’t seen him in ages.’ I pulled out a recent photo.

‘That’s him?’ the friend shrieked. ‘You’re kiddin’ me. Look how Irish he looks. We used to call him that, Irish, I don’t know why. He loved it. Sonny O’Hara. Ha! He’s an Irishman. He always had the blarney alright. Whaddya know?’

At 1pm I went out on the balcony to smoke a cigarette. Fifteen minutes and I would redefine my life. I felt sweat rise on my skin. I looked out on the calm Pacific, the beach filled with shapely sunbathers and muscular beer drinkers. A taxi pulled into the reserved spot at the front of the hotel: my getaway car.

One floor below, at the lobby level, my father entered the hotel. He was in his tuxedo. I opened the door of the room, went back to the balcony to ponder my fate.

‘Deep thoughts?’ my father asked, suddenly next to me.

‘Something like that,’ I said.

‘When I was your age ...... ’ he began, keeping his eyes on the ocean. I recognized myself in his profile: the angle of the neck, the lips pursed prior to speaking, the projection of unwarranted hope. I wanted to laugh, but instead tears came to my eyes. ‘....... just like you, I stood at the water’s edge, and wondered what it all meant. I was home on leave, about to go back to Japan. I wanted to get to my life already. I wasn’t scared of dying ..... I was scared of missing my life, or of it being a disappointment when I finally did get there. I was being tested. I wondered how I measured up, why some people seemed better than me, others worse, how some bypassed me .........’ -- now he turned to me, and I faced him. Tears ran down my cheeks. He continued: ‘.............. I was asking all those questions then, twenty-two just like you. The ocean was huge, you could get on a boat and go around the world, and I was on a solitary path ..........’

He was already deep into his mythology by age twenty-two. He had become a Catholic, had not told his elderly parents, who were to die unaware. He began his lifelong effort to carry that burden of duality, dividing his world. The war was his first chance to create himself anew with strangers.

On his way to Japan, where he was to be part of a flight crew dropping bomb warnings over Korea, he had passed through California, and it had become lodged in his consciousness.

It took him 18 years to make the move. He and I did it together in 1971. 'New York is a dying city,' he had said many times.

‘It’s a lot like what you are facing now,’ he told me on the balcony of the hotel. ‘The unknown, the feeling you were going to miss the big parade, and how to measure yourself. It was frightening.’

I had grown tranquil; Sonny had hit a note that rang clean and true.

‘But dad,’ I said, ‘you were headed to war. I’m just going into a stupid marriage.’

‘Don’t get ahead of yourself,’ he warned. ‘You’re imagining every negative possibility. Don’t direct traffic on an empty road. If you do that, when the cars show up, everything will look like a potential accident. You can’t live like that.’

The room phone rang. ‘Do you still want that taxi?’ the concierge asked.

‘No,’ I said. ‘My father’s here. He’ll take me.’ I lay the phone gently in its cradle, kept my hand on it for an instant, closed my eyes.

‘You need a ride?’ Sonny asked. ‘I can take you.’

‘Didn’t they send you here to get me?’

‘No, I got your voice mail. Thought maybe you wanted to talk.’

‘I did,’ I said. ‘It meant a lot, Dad, thanks. You really helped. But they forgot about me. No one was picking me up.’

‘Sounds like you had a cab ready,’ he noted.

4. The Long, Long Days That Follow

W e followed the script: no Florida relative wasted their money, no family memory would include the indignity of cancelation. The bride’s weight loss was not in vain, the costly photographs can be shown in their book. Like most American weddings, the undertow was deadly. Avoiding that, there was only a shell to navigate: a reception line, various rituals, gifts, the obligatory dance, the slow decrescendo into the long, long days in which we would play out our lives.

We left for Las Vegas the next morning. The bride had started harping on me about trivial idiocy again once the ceremony was over; I had no leverage now. I came out ahead in blackjack, swam in the crowded pool, stood in line for dollar buffets of warmed-over food. After four days we got back in the car and returned to the scene of the crime.

My in-laws barely acknowledged me. My mother-in-law was about to go on a Caribbean cruise with cousins and childhood friends, and she could think of nothing else. I could tell that my wife wanted to go very badly. She had been on the last few with her mother and cousins and it had taken on a cultish aspect. Details were private but they would whisper or make obscure references and exchange telling looks and shut down if anyone was in earshot.

‘Go,’ I told my wife. But she didn’t believe I meant it, so she suffered with a martyr’s bruised nobility and in great pain accepted the limitations of married life and stayed by my side as the post-wedding episode wound down. My father was not seen after the wedding was over. Relatives who had traveled lingered.

On the night before we were to head back to our apartment a few miles from the western Arizona Air Force base, my mother, who was also departing the next day, called for a family dinner summit, and so dutifully we all gathered in a generic Southern California dinner spot – my sister and brother, my wife and I and Arlene, my dramatic mother, letting us know ahead of time that she had important news.

We were in a secluded corner of the restaurant, in a large booth that could have seated ten. Arlene wasted no time in getting to her subject.

‘I’m leaving your father,’ she told us.

We looked at each other in confusion. ‘Haven’t you already left him?’ I asked.

‘Not in a way that was permanent. He’s just sub-letting across town. He’ll be back if I stay in our old apartment, so I’m moving, I’m filing for divorce.’ She was tearing off pieces of a dinner roll and chewing them slowly, and sipped iced tea. ‘There’s more,’ she told us.

‘This is going to be bad,’ my sister commented.

‘Don’t interrupt,’ Arlene insisted. ‘I’ll take questions at the end.’

I n the lead-up to the wedding, my grandfather, her father, died at the age of 72. He had been relearning how to walk after he lost a few toes to diabetic gangrene, but in his efforts he may have liberated some fatal bacteria because he contracted sepsis, an incurable blood infection, and was gone in a month. He did not want to be in a wheelchair for the wedding.

She was stoic about his passing, on the surface at least. He had lived either with or near them for two decades. He adored Sonny, who was a very attentive son-in-law and handled a lot of details for him – Social Security, Medicare, safe deposit boxes –

‘He didn’t steal from Grandpa?’ my brother asked, leaning forward.

‘Don’t interrupt,’ our mother insisted.

A week after the funeral, she mentioned her father’s assets to Sonny, who said, ‘I was going to tell you about that.’ He sat down at the kitchen table and told her that Jack’s $40K cash CD was lost in the bad Argentine deal. Her mother’s jewelry, held by her father in a in a safe deposit box, valued at about $60K, had been sold off one-by-one to cover losses. There was no recourse: Sonny had squandered community property. Her father had not known anything was amiss. The $40K had generated a $300 monthly interest check, which Sonny paid diligently out of his own pocket for close to three years.

Arlene finished her tale on that note. We had all been bursting with questions and comments but now no one seemed able to produce a word. That $300 was worth nearly $1700 in today’s money; and he had somehow hustled it up every month for three years. The stress must have been enormous. I thought of him walking the through the apartment late at night, haunted by the losses, the solitude of failure. But he made those payments: life as theater.

This was my father: the man who told me about empty roads, and the mirage of traffic, that every cluster of metal and speed was not a death-crash. He had come that day at the hotel to see me, knowing I was in crisis. Had he not ........... this would have been a different story.

We ate dinner, embraced, went off to our lives. ‘I’ll be fine,’ our mother assured us, and she was.

5. Lightning Strikes

I returned to my post and in 1979 I was staring down the barrel of the future when I was assigned to a remote outpost in Iceland for my final year, no family allowed. My marriage was over the day I boarded the plane for that assignment. The road was empty again.

I returned in 1980, with ties to nothing. I could have gone anywhere. I paused for a moment as I walked through the gate into civilian life, took it all in, and headed west, looking for my father. I found him. I was 24; he had just turned 49.

I began to build a life, became a father myself. The boy had become a man, had grown into the roles, just as hoped. Reality caught up to the story, at least for a time. That would have been the right ending, but there’s only one ending, and it's not here yet. No need to direct traffic.

W hen I was 12, I pitched a no-hit game in the Little League championship quarter-finals during a summer thunderstorm. Lightning hit a tree, cracking it in two, within fifty feet of the first baseline, seconds after the final out. The rain came down so hard we couldn’t even celebrate; we ran f0r cover in the dugout. The umpire told my father: ‘Your kid has the sang-froid of an assassin.’ In the car Sonny was playing with the phrase silently, trying to put his lips around it.

On the drive home, a wave of water so powerful fell on us it stalled the car and we were almost floating on mid-Queens Boulevard for about ten minutes before we could get the car started again.

About 10 minutes from home we stopped in at our favorite diner and were greeted with applause and confetti. Sonny had someone call ahead and make the arrangements. Food was brought out and as we ate they wanted a blow-by-blow of the game, the rain, the lightning, and the final strike, ‘the pitch so fast the ball was the size of a pellet,’ as my father described it.

Near the end of the evening I sat with Jack, my mother’s father who didn’t make it to the wedding, whose assets were lost in Argentina – but all of that misery was far in the future. He poured himself a beer and gave me a half-cup and we toasted.

‘You did good,’ he said. ‘We’re proud.’ I nodded, tried to keep the bitterness of the beer out of my face as I swallowed, didn’t succeed. ‘Second sip will be better,’ Jack assured me.

‘Come a long way from two years ago,’ he reminisced. ‘Me and your father picked you up after the last game of the season and he asked you – remember?’

I was swallowing beer, feeling it in my bones. Jack went on: ‘Sonny was furious when you told him you didn’t get picked for the All-Star team, was ready to find that weasel coach and tear him to bits. He was pounding the steering wheel and cussing.’

I remembered. It was a very hot afternoon. Kids were running around with garden hoses, spraying each other; our windshield was hit with a wave of water.

‘I didn’t deserve it,’ I told my father.

Something in the car deflated. I cracked a window, let the steamy heat dissipate. I said: ‘I had a bad year.’ I was in the backseat, and they both turned to look at me. I was not a kid from whom you’d expect an admission of this sort. ‘You really feel that way?’ my father asked. ‘Yes,’ I had said.

‘What came over you?’ Jack asked, adding a little beer to my glass.

I didn’t have a coherent answer. I was just tired of all the falsehoods and in the car it hit me all at once and ........ I didn’t want Sonny to fight for me. I wasn’t worth it. But I didn’t have the words to explain it then and I sat at the table with Jack two years later and was feeling the beer and the no-hitter and the lightning. It was Fathers’ Day. Jack asked me again: ‘What came over you?’

‘I didn’t earn it,’ I told my grandfather. ‘I told the truth.’

This was one of our moments, a short-lived peak: Grandpa’s money was still intact; Sonny had not yet yielded to full corruption; at 12, I had delivered on the 10-year old’s internal promise to give a better account of myself. And my mother, the best and purest of all of us, could arrive to this place with excitement and pride.

I saw my mother coming through the front door of the diner; Sonny led her in with a proprietary hand at the back of her waist. Her gaze darted from spot to spot, looking for me. As I went to her she opened her arms and I fell in to the rare embrace. She whispered, ‘This is real?’ and I assured her it was, and she asked, ‘A tree cracked in half?’

‘Not exactly half,’ I said with my newfound honesty, ‘but close.’

She looked at me suspiciously. ‘Wait, have you been drinking beer?’

‘With grandpa,’ I said.

‘Hmmm,’ she intoned, deciding not to fight it. In the bar, my uncle Al brought her a gin and tonic. Al was married to Sonny’s sister Isabel. He was a modest man who always looked out for me. I knew his bio well enough to write it. As a teenager he ran errands for important people, one of whom took an interest in him and gave him a stake, which became an international textile business.

My mother handed me a card I had gotten for Al that she had remembered to bring. Al always made sure I had a little birthday party, even if it was at his house with 2-3 people. I found him in a secluded booth, calculating figures on a legal pad. ‘Ach,’ he exclaimed when he saw me. ‘Currency rates! They change all the time! If I had one wish ............ the world should stop, 5 minutes a day, let us catch up.’ I handed him the card, and he read the quote aloud:

In his time, one man plays many parts.

Fatherhood is your best.

He met my eyes with his own, expressive and dark behind his reading glasses. ‘Donnie, your father raised a helluva kid,’ he said. ‘Don’t forget that. You don’t come from nowhere. Down the road, make sure you give him credit.’ It was an acknowledgment that I was already brutally critical of my father.

I said nothing. Uncle Al asked, smiling: ‘That tree splitting in two was bullshit, right?’

‘It happened,’ I told him. ‘Lightning struck. You know me, Uncle Al. I speak the truth.’

E ach Fathers’ Day now is filled with awe, as in awestruck, as in awful, and awe-inspiring, awe being a word that contained its opposite: the ambiguity, the contradiction that felt like home, as life was a contradiction, negating in one moment what you thought had been proven in the prior one. The smartest of us learn to improvise: life as theater.

Whoever is doing the casting, people bring their unique gifts. As Al advised: credit my father for his share in whatever is good and worthy in me. For the rest of it: That’s where I earn the big bucks, taking responsibility. And forgiveness has a role, the simple equation of understanding evolved from love, easily perceived by me in synesthesia’s bold unflinching colors, etched into the face that stares back at me in the mirror, looking more like the face of my father each day.

We were adults when my sister handed me an envelope addressed to Hal Harris Phu. ‘What’s this?’ she asked. It was from a publishing house in Delaware. I was fearful for a second: I had been many things, but there was no way I could be a Phu. It had been years since I needed to act on my father’s theatrical ambitions, but the rush was familiar: Curtain up.

‘The ink has faded,’ I realized. ‘It’s meant to be Hal Harris, PhD. Familiar territory. Nothing to worry about.'

About the Creator

Donn K. Harris

WRITER, CREATIVITY CONSULTANT, NEVADA CITY, CA.

Calif Arts Council Chair, 2015-18; led Ruth Asawa/ Oakland Arts Schools, 2001-16; Director of Creativity, SF Schools 2016-19. Created nonfiction genre, Speculative Sociology; 4 published novels

Enjoyed the story? Support the Creator.

Subscribe for free to receive all their stories in your feed. You could also pledge your support or give them a one-off tip, letting them know you appreciate their work.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.