The Trial of the Century: The Murder Which Rocked Chicago.

The Genius of Arrogance.

Pictured above is a 27-year old Nathan Leopold, a man who formed half of the duo that killed a teenage boy.

Born in the winter of 1904, Nathan was dubbed a child prodigy the moment his first words passed his lips at just four months old. As he got older, he became fluent in five languages and by the time he was nineteen, he graduated from the University of Chicago with Phi Beta Kappa honours — the pinnacle of academic honours in the United States. On top of that, he achieved recognition in the field of ornithology.

Growing up, he was on friendly terms with another boy called Richard Loeb as they lived near to one another. Like Leopold, Loeb ended up attending the same university. There were a number of other parallels between the two as well, as they were both born into wealthy families with a Jewish heritage, and both were exceptionally intelligent.

Thanks to the oversight of a disciplinarian nanny, Loeb was able to skip several grades at school and attend the University of Chicago at fourteen, before later transferring to the University of Michigan, where he became its youngest graduate at seventeen.

During their teenage years, they developed a mutual fascination with philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche, particularly his concept of the Übermensch, a vision of the ideal, superior man. One that transcends normality to create and impose his own sublime version of morality on mankind. A superman.

The two friends were thoroughly intoxicated with this idea of superior beings, even believing they themselves belonged to this preternatural group, and that it meant they weren’t bound by the normal ethics and laws that ruled mere mortals. Leopold even wrote as such in one of his letters to Loeb:

"A superman ... is, on account of certain superior qualities inherent in him, exempted from the ordinary laws which govern men. He is not liable for anything he may do."

The two genius boys were yin and yang — Leopold was the introspective and academically voracious half of the duo, and Loeb, the fun-loving and socially savvy half. Consequently, they fed off one another and nurtured a friendship so intense that they ended up becoming sexually intimate.

The pair started putting their philosophical theory into practice with a series of low-level crimes, usually petty theft and vandalism. Emboldened by their successes, they upped the ante to more serious misdemeanours, including arson. It wasn’t enough though; their ravenous hunger for recognition wasn’t being satiated, as the press weren’t paying the crimes any attention.

Leopold and Loeb, now nineteen and eighteen respectively, decided thereon to commit one of humanity’s greatest sins — murder. They knew that it would attract a massive amount of public attention, and provided them with the chance to prove their mettle by planning the “perfect crime”. They spent seven months meticulously plotting every detail, covering all ground to ensure their success.

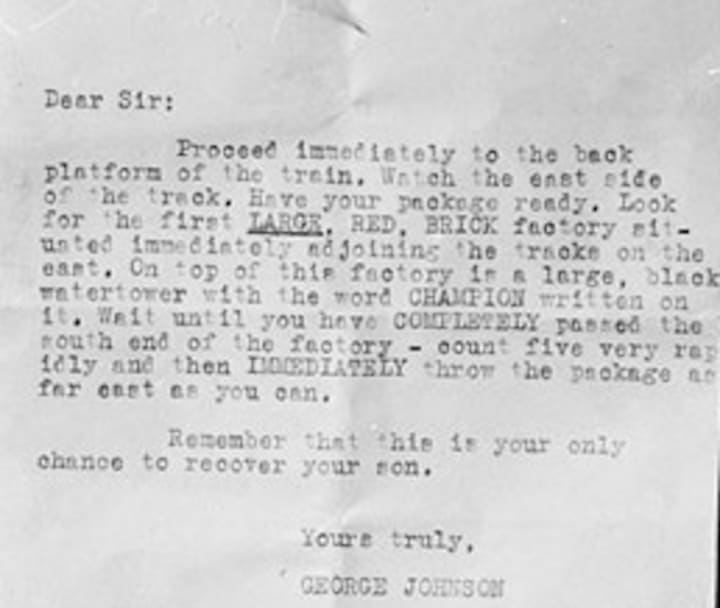

They decided to set up a ransom to obfuscate the true motive behind the crime, delivering this letter with its very specific and elaborate steps to be followed, and then, they only had to decide who was to be their victim.

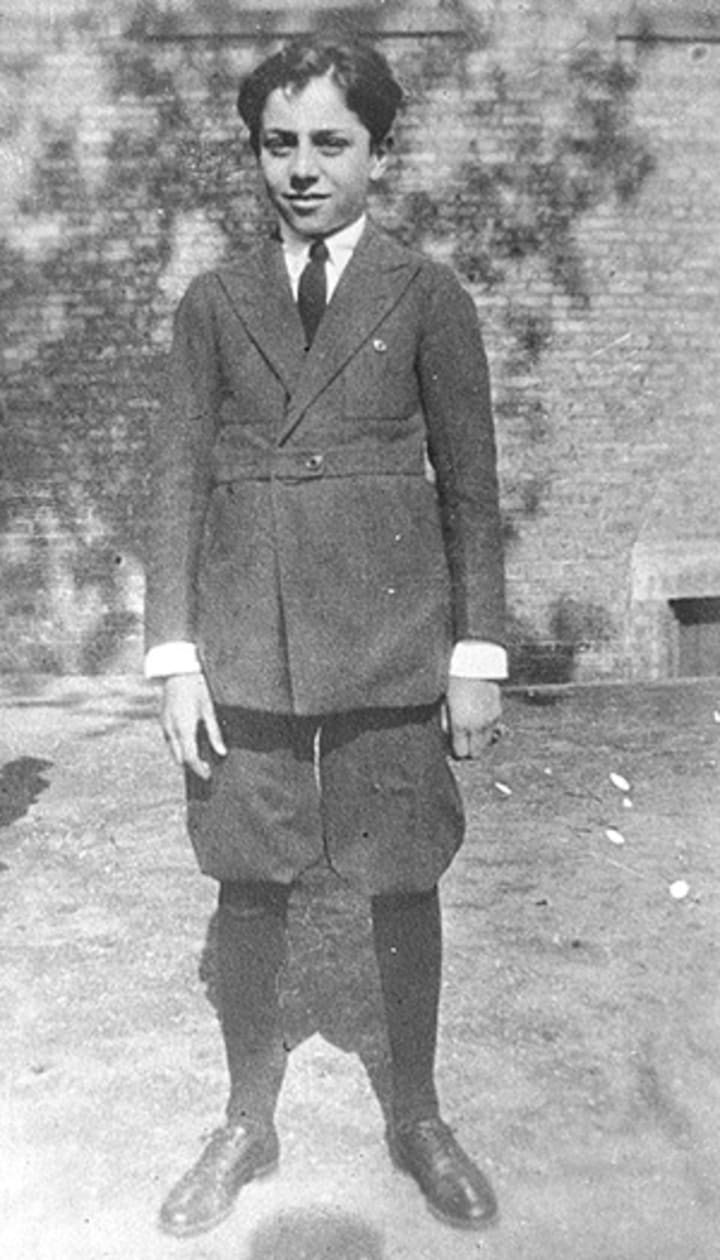

14-year old Bobby Franks.

Bobby was someone the duo knew, Loeb in particular. After all, he was his second cousin, neighbour and someone who’d played tennis at his house a number of times.

On the fateful day, the men lured him into their rented car as they drove by and shortly afterwards, struck him in the head several times with a chisel. Following that, the boy was gagged and died shortly thereafter. They took his body to a predetermined dumping spot twenty-five miles south of Chicago, stripped him and to conceal his identity, poured hydrochloric acid on his face as well as his genitals, the latter act to hide the fact that the boy was circumcised, an obvious clue that he was Jewish.

Then they shoved his corpse into a culvert and drove off.

They returned home, destroyed their blood-stained clothing and cleaned the blood off the car’s upholstery, before spending the rest of the night playing cards. Little Bobby had already been reported missing by the time they’d returned home, and so they attempted the ransom, but it went wrong when a nervous family member faltered. Soon after, the boy’s body was found and the ransom abandoned altogether.

The pair destroyed any remaining evidence linking them to the crime, and went about their lives as normal. Loeb kept his head down during this time but Leopold, drunk on arrogance, spoke freely to reporters and detectives. He even said to one detective:

"If I were to murder anybody, it would be just such a cocky little son of a bitch as Bobby Franks."

The wheels began to fall off the wagon when a pair of glasses was discovered near Bobby’s body. Even though the frames and prescription were entirely ordinary, the hinges were highly unusual — so much so that only three people in Chicago had purchased them, and Leopold was one of them. He was questioned about it, but claimed that he dropped them after a bird-watching session during the weekend prior.

The excuse wouldn’t last long though, as the destroyed typewriter that was used to write the ransom note was recovered from a lagoon, and led to both men being questioned. They fabricated a short-sighted alibi about having picked up women on the night of the murder, but Leopold’s chauffeur confirmed his car had been in for repairs that night. With their lies unravelled, they had no choice but to confess. However, they each claimed that the other was the murderer, and that they themselves were only the driver.

They also admitted to being in it for thrills and Leopold, curious to know what murder would feel like, declared his disappointment in that he felt no different afterwards.

The trial that followed was dubbed the “trial of the century”, and the Loebs hired renowned defence lawyer Clarence Darrow, who was paid $70,000 for the job — equivalent to $1 million in 2020. A staunch opponent of capital punishment and knowing they were facing harsh punishment either way, Darrow built a case based on a plea of not guilty by insanity, hoping for a sentence of life imprisonment instead of the death sentence.

Darrow’s pièce de résistance was a twelve-hour plea, one that has been called the finest of his career. The thirty-two day trial came to a close in September 1924 when the judge, persuaded by Darrow’s arguments, ended up sentencing them both to life in prison, as well as an additional ninety-nine years for the kidnapping.

Both of them were sent to prison and a month later, Loeb’s father died of heart failure. Loeb himself would only go on to live twelve more years, dying at the age of thirty after a vicious attack from a fellow inmate, which saw him slashed fifty-eight times with a razor.

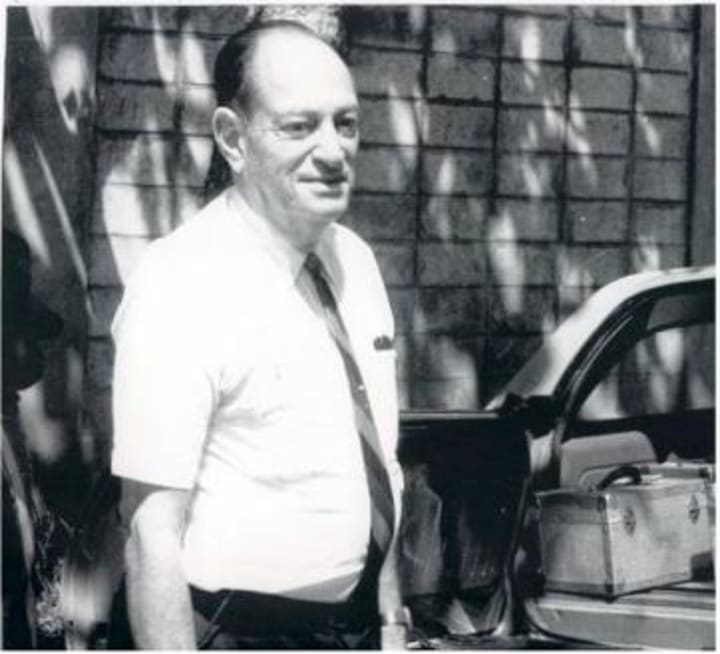

Leopold’s story following imprisonment is an unusual one for a criminal of his class, as he ended up being a model prisoner. He made numerous efforts to better prison conditions by reorganising its library, revamped the school system and taught its students, whilst also doing volunteer work in the prison hospital. He also released an autobiography, Life Plus 99 Years, during this time.

After numerous parole denials and having spent thirty-three years in prison, he was released and shortly thereafter attempted to set up a charity funded by his book’s royalties. It was to be called the “Leopold Foundation” and was “to aid emotionally disturbed, retarded, or delinquent youths.” His charter was voided though, on the grounds that it would’ve violated his parole terms. He was given a home and job by the Brethren Service Commission, a Christian charity, who took him on as a medical technician working at its hospital in Puerto Rico.

He subsequently moved, got married to a florist named Trudi Feldman, and earned a Master’s Degree at the University of Puerto Rico. He went on to teach, then became a researcher for a social service programme. He also worked for an urban renewal and housing agency, and did research on leprosy.

Then at sixty-six, he died of a heart attack induced by his diabetes, and his corneas were subsequently donated.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.