Real neuro-criminal law: At what age are you fully responsible?

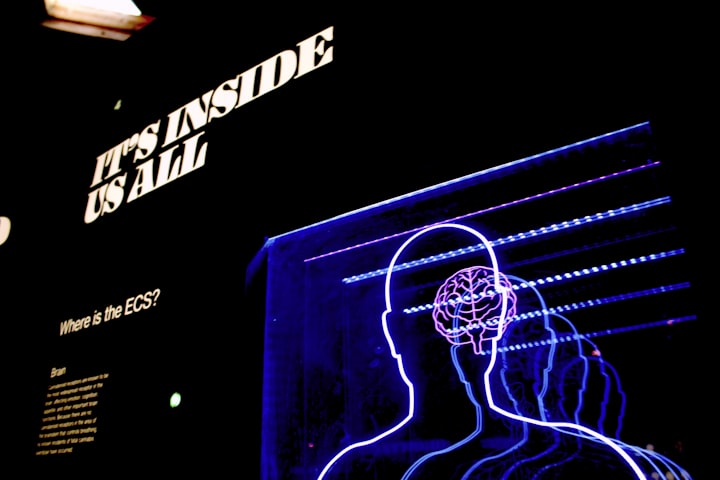

How neuroscience influences the law, using the example of Dutch criminal law for adolescents.

Today I am returning to a classical topic and also one that is very close to my current research. I have to admit a mistake right at the beginning: I have always criticized the exaggerated statements of leading brain researchers who called for nothing less than a revolution in criminal law. In my criticism, I mentioned several times that there is still no country with a “neuro-criminal law”.

Now I still think that the statements of these researchers are exaggerated. However, for too long I have overlooked the fact that the country in which I have lived for the most part since 2010, of all countries, has a genuine neuro-criminal law: the Netherlands. This is because the maximum age for the application of juvenile criminal law was set at 1 April 2014 — no April Fool’s joke! — was raised from 20 to 22 years. And the legislator has explicitly cited findings from brain research in the justification for this, namely on the brain development of adolescents and young adults.

This may not be a revolution, but it is a little revolution. This is especially true in comparison to facts that have been intensively covered in the media, for example when a court somewhere in the world referred to findings from brain research or genetics. (Most of the time, this then had a mitigating effect.) In the following I will discuss how it came to what is now called the Dutch criminal law for adolescents; to what extent its neuroscientific justification is correct; and how, more generally, science should and should not inform politics.

In any case, the basic ideas we are discussing here can be applied to the criminal laws of all countries: At what age are we legally responsible? And what role do scientific findings play in answering this question?

Background

Let’s go back to 2010 when I had just come to the Netherlands and was going through a difficult time in politics: The new government was formed after the parliamentary elections on 9 June and lasted for a full 127 days, leading to a minority government tolerated by Geert Wilders’ PVV, the economic liberal VVD of Prime Minister Mark Rutte with the Christian Democratic CDA. This was to last, in passing, only for around two years.

Unsurprisingly, security played a major role in the election campaign. This was also reflected in the coalition agreement entitled “Freedom and Responsibility”. High on the agenda was, in particular, the cross-border behavior of so-called risk youths, both as individual offenders and in gangs. Adolescents and young adults — in science they are often referred to as “adolescents” — would account for 30% of all suspects.

The State Secretary of the Ministry of Security and Justice referred to a report just published at that time by the Council for the Application of Criminal Law and the Protection of Minors, an independent public body with an advisory function,[1] which states that the mental functions for responsible behavior are not fully developed until after the age of 20. In particular, it deals with: (1) impulse control, (2) the consideration of long-term consequences, (3) emotion regulation, and (4) empathy.

These thoughts are more fully formulated in the explanatory text of the law, as it finally applies since April 1, 2014. It states, again concerning the aforementioned report of the Council

“The fact that specific risk behavior occurs between the ages of 15 and 23 can also be attributed to the incomplete development of important brain functions. The core of what science teaches about this is that the mental development of young people does not stop when they reach the age of 18 and that essential development takes place precisely after that age. The still incomplete emotional, social, moral, and intellectual development is also a cause for the fact that a large part of (juvenile) crime occurs during adolescence but also ends before the age of 23”.

From the explanatory memorandum to the law. S. Phlegm

Here, brain development and personal maturity are related to each other and these two, in turn, are related to the problematic behavior of adolescents and young adults. Now, of course, the nervous system is subject to our psychic abilities, even if we often cannot find a one-to-one connection. This is a big discussion in philosophy as well as in science, which I have recently summarized (The little basics of the body-mind problem).

Here, instead, I will examine the exact relationship that the Advisory Board makes between brain development and mental abilities, and to which the new law refers. This is specifically stated in the report in the section on “The biological and psychological development of young people”:

“It is only around the age of 25 that functions such as planning and flexibility are fully developed in the prefrontal cortex. Other psychological functions such as the braking of impulses (“inhibition”) or the suppression of other distracting impulses and associations (“interferences”) only come to full bloom after the age of 20. This means that specific risk behavior, which often occurs in young people between the ages of 15 and 23, is partly caused by the still incomplete development of certain important brain functions. The most significant development of these brain functions only occurs after the age of 20. Until this age, other people, especially friends of the same age, still have the greatest influence on making important decisions. […] Research on the functioning of the brain using scanning techniques shows that young people are often still controlled by the nucleus in the brain, which respond to direct rewards, the nucleus accumbens, while the brain of people over 25 years of age shows more activity in the almond nucleus and prefrontal cortex. […] It is only when the prefrontal cortex is mature that the young person is better able to regulate his or her emotions than before.”

From the report of the Council for the Application of Criminal Law and the Protection of Minors, Übers. S. Phlegm

Thus the explanation was — at least on paper — complete: immature brain = immature personality = less responsibility before the law. Thus, under the new law in the Netherlands, it is now possible to treat a young adult up to the age of 22 under the rules of juvenile criminal law “if [the judge] finds reasons for this in the personality of the offender or the circumstances of the offense” (Article 77c, paragraph 1, Dutch Criminal Law). Incidentally, this can also have consequences for young holidaymakers from German-speaking countries who break the rules on Dutch soil.

Interim balance

An interim comment on this: In the election campaign and the coalition agreement mentioned above, tougher action against young offenders was promised. However, the measures of juvenile criminal law (such as social work or punishments in juvenile prisons) are much milder than those of adult criminal law. In the case of younger offenders, the pedagogical motive is in any case predominant over the punitive (in technical jargon: retributive) motive, because it is assumed that people at this age can be influenced more positively in this way.

Even if I consider this approach to be sensible and correct, there is a certain “taste” in misleading the voters in this way: One promises one thing and does another. For the sake of completeness, however, it should be noted that at the same time the sentence under juvenile criminal law was raised for some offenses. This gives a mixed picture.

But let’s stay with the contribution of brain research: As far as I know, this was the first time worldwide that the legislator addressed the results of neuroscience in such detail and directly. In this sense, the Netherlands thus has what I believe to be the first real “neuro-criminal law” in the world.

Let us now take a look at the specific scientific findings in question. In the longer quotation from the report above, I have — in the interests of readability — removed the references to the three studies by Adleman and colleagues (2002), Casey and colleagues (2005), and Paus and colleagues (2001). What do these studies say and do their findings fit in with the report and the explanatory statement?

Analysis of the studies

First of all, it is striking that these studies were already outdated at the time of the legislative process. At that time there would have been more up-to-date and better publications on brain development. But let us leave that aside.

Adleman and colleagues have investigated the “Stroop test” in magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) in adolescents and young adults, which is very popular in psychology. In this test, color words (such as “green”) are displayed in a matching or different color (e.g. red). It takes longer to determine which color a word as if the word and color do not match. Also, the impulsive reaction of indicating “green” in red letters where “red” would be the correct answer must be suppressed. This test is therefore often regarded as a control and inhibition test.

The three age groups in this experiment were children aged seven to eleven years (N = 8), adolescents aged twelve to 16 years (N = 11), and young adults aged 18 to 22 years (N = 11). Here the small group size is immediately noticeable. It is impossible to derive representative results from such small samples. In MRI research, this is defended concerning the high costs of the examination: depending on the length of the measurements in the MRI scanner, this can quickly cost €500 to €1000 per person, in this study €15,000 to €30,000 for data collection alone. But this is, of course, a purely pragmatic argument, not a substantive one.

In the most important study of my cognitive science doctoral thesis at the University Hospitals of Bonn, for which I examined lawyers in a brain scanner — for the first time in the world, as far as I know. That was still a small number, but it was an exception by the standards of the time.

By the way, this was not without challenges to investigate lawyers. Some people, for example, brought a witness (for example the wife) without an agreement and then put me under pressure to medically evaluate the brain images, even after they had been made aware several times that I was not trained for this. Well, nobody sued us at that time.

But let’s get back to the study by Adleman and colleagues: In addition to the small sample size, before we look at the results, there are some peculiarities about the age groups. After all, the new Dutch law amounts to treating people differently before and after the age of 23. In principle, the study cannot say anything about this, because no people over the age of 22 were studied. But does it perhaps at least allow statements to be made in a comparison of 12 to 16-year-olds with 18 to 22-year-olds?

The publication reports statistically significant differences for these two age groups — the age of criminal responsibility in the Netherlands is already twelve years — while the new law treats them more similarly. These differences were found in the prefrontal cortex. And there were no significant differences between children (seven to eleven years) and adolescents, of all people, where the law treats these groups differ in principle. The study by Adleman and colleagues, therefore, seems to contradict rather than support the proposed law.

Does the publication by Casey and colleagues perhaps paint a different picture? This is an overview paper that summarizes various studies. However, these authors report that the brain of a six-year-old already accounts for 90% of the volume of an adult brain and that sensomotoric, associative, and prefrontal brain regions are almost completely developed by the age of 16. This also directly contradicts the Council’s report and the explanatory memorandum.

Does the third and last neuroscientific work cite, that of Paus and colleagues, perhaps bring salvation? Unfortunately not: This is a summary of structural brain studies on human brain development up to the age of 30 years (older people were not studied for this). According to the results, on the one hand, it is now the case that brain development never stops completely; on the other hand, the differences between individuals are sometimes so great that a six-year-old, for example, may have a larger bar connecting the two brain hemispheres than a 16-year-old. So these findings cannot support the legislative initiative either.

Laws, behavior, and brains

At this point, I think a general point is appropriate: the law defines clear age limits, such as the age of criminal responsibility as of twelve years — in Germany in Austria, by the way, as of 14 years, in Switzerland, however, as of ten years and before 2007 even as of only seven years! — It should be clear that these are laws made by people, namely politicians in power. Of course, it is not the case that in the brain of a 12-year-old, in Germany with a 14-year-old everything suddenly changes as soon as he blows out the candles on his birthday cake.

Brain development takes place differently from one individual to another and according to a continuum, not in stages as described by criminal law. In this respect, it is illusory to find a clear correspondence between our norms in the brain. This is also true, by the way, of the search (which has been very unsuccessful for over 170 years) for neuronal correspondences of psychiatric disorders, whether they are attention disorders, anxiety disorders, autism, or depression, as I explained elsewhere (The ABCs of Psychiatric Disorders).

So, at best, one could look rather roughly and very generally whether the neuroscientific findings fit the age limits of the law or not. In the case discussed here, this was not the case. But would it have made a significant difference if the results had been in line with the legislative initiative?

Criminal law regulates behavior that is prohibited in a society. In liberal constitutional states, the rule is: everything is permitted that is not illegal at the time of the crime. This is separate from the question of the circumstances under which people are held responsible for breaking the rules. Criminal law in many liberal constitutional states (I am not aware of any counter-example) presupposes guilt as a precondition for punishment, and guilt, in turn, presupposes the ability to understand and control. (Incidentally, there is no mention here of the “free will” repeatedly conjured up in recent years by philosophers, psychologists, and brain researchers).

This means that a person can only be punished for a forbidden act if at the time of the act he or she knew or had to know sufficiently that his or her behavior was forbidden; and if he or she then also had sufficient control. This is simply the criminal law dogma in force in many countries.

Classical counter-examples include coercion, for example: “Either you give me your painkillers or I’ll slaughter you!” Then you wouldn’t be punished for a violation of the narcotics law. Also, acts of drunken stupor or psychosis, such as: “My boss was possessed by evil demons, so I had to kill him.” As is well known, criminal law here has other coercive measures to protect society, such as compulsory therapy or preventive detention. These are, the difference is legally important, but formally they are not punishments, even if the person concerned might experience them that way.

The law is pragmatic

This raises the question of how much we need to know about the brain development of humans to establish functioning rules about the responsibility, insight, and control abilities of humans. If people of a certain age group generally behave responsibly, except perhaps in certain situations such as tests of courage or peer pressure, then we can assume that this has something to do with brain mechanisms in a certain social context.

But then we already know this from our behavior and the knowledge about brain mechanisms does not add anything essential (brain scanner or behavior?). Of course, it can still be scientifically interesting to study the concrete brain structures and functions of such behavior. However, this is not necessary for the definition of practical rules that do justice to humans. The law is simply pragmatic. This calls into question the necessity of “neural law”, which is praised by some.

A good example of this is a decision of the US Supreme Court in 2005, about which I already wrote extensively in my book on the neuro-society (2011): At that time, the question was whether murderers who were minors at the time of the crime could be responsible for their deeds enough to deserve the maximum penalty (in some US states the death penalty). The defendant was Christopher Simmons, 17 years old at the time of the crime, who broke into the house of an elderly woman with friends, tied her up and abused her, finally brought her to a bridge, tied her up and threw her into a river with a plastic bag over her head and let her drown. Such cruelty must be thought of first!

The majority of the highest US judges concluded (I will come to a dissenting vote in a moment) that youth, even after such a terrible act, cannot be responsible enough for the maximum penalty. In the reasoning it was said:

“Three general differences between young people under the age of 18 and adults show that juvenile offenders cannot reliably be considered the worst offenders. Firstly, as all parents know and as scientific and sociological studies cited by the defendant […] tend to confirm, ‘a lack of maturity and an underdeveloped sense of responsibility is more common and more understandable among young people than among adults. These characteristics often lead to hasty and unbalanced actions and decisions’. …] It has been found that ‘young people are statistically overrepresented in virtually all categories of reckless behavior.’ […] Recognizing the relative immaturity and irresponsibility of young people, virtually every state prohibits under-18s from voting, serving on juries, or marrying without parental consent.”

Roper v. Simmons. S. Phlegm

Interestingly, this very indirect reference to scientific studies — “as all parents know and the quoted studies tend to confirm” — has produced strange flowers in the euro right discussion that would deserve an article of its own. I will only ask here once: How desperate must one be as an academic when one deduces from this statement of the judges that the neurosciences have influenced the highest judicial decisions? One would be surprised at the number of eminent Members who have taken part in this game! (Probably to get project funds for euro rights research afterward, which has worked often enough. True is what is useful!)

Behavioral knowledge has priority

But my point is made clear by the verdict — and more cases could be used for support — that because of the behavior of young people we already know more than enough to justify a different (criminal) legal treatment. And if these behavioral observations are clear enough, it doesn’t matter what the brains of young people look like. It would at best be a problem for the brain researchers if they could not explain these clear differences in behavior, but not for the legislator. After all, it is not certain brain processes that are prohibited, but only certain actions.

A breakthrough for legal practice would probably only come about — and I am writing this also under the impression of my previous lecturing activities at the German Judges’ Academy in Trier — if neuroscientific procedures could be used to determine the responsibility of a specific individual. But that would then have to relate to the time of the crime.

The methodological challenges are enormous, however, as I once formulated with a British colleague from neuropsychology in 2009. This is not least because the prevailing methods — and this also applies analogously to many studies in medicine, psychology, nutritional science, and other disciplines — do not capture the individual, but rather what is the same in all test subjects. Even worse: individual differences are sometimes even interpreted as measurement errors!

In a science that, like brain imaging research, excludes subjects simply because they are left-handed (this has happened to me repeatedly, fortunately, because many such studies are boring), have a mental disorder (i.e. 40% of the population, according to some epidemiologists? ), have other illnesses and take certain drugs because they are claustrophobic or are women and do not take the contraceptive pill (to balance hormone fluctuations), one must assume that the results are speculative. Courts cannot allow themselves this luxury of excluding so many individually different people from their proceedings. Then there would probably be hardly anyone left to condemn. This branch of the “new law” therefore remains dreams of the future.

Science and laws

Thus, the question of the influence of science on the law remains. The researchers of the neuroscientific work discussed here cannot be accused of misinterpreting it. However, it is already very embarrassing for the Council for the Application of Criminal Law and the Protection of Minors to quote studies that suggest the exact opposite.

But nobody in the Netherlands seems to have noticed this so far. The fact that the legislator uncritically took these parts from the report does not, of course, inspire confidence. Perhaps they were simply satisfied that the interpretation presented fitted in with the thrust of the report.

But there are enough examples where researchers are not so innocent. We have seen it: When politicians wanted expert opinions that nuclear power was safe, there were those from the scientific community. A few years later, the opposite conclusion was called for. Again, suitable experts were found who came to the desired conclusion.

I also remember well the legalization of circumcision of male children: Some sexual scientists declared the practice harmless, for example with the argument that circumcision in certain African countries with poor hygiene standards reduces the risk of HIV infection (How the research on the circumcision debate contradicts itself).

As I have already indicated, questionable constellations also occurred about neuroregulation. If a crime happened somewhere in the world and later a genetic or neuronal irregularity was found in the perpetrator, it went around the world as a sensation. If any court accepted neuroscientific findings, then this too was taken up in many media.

Many things turned out to be problematic on closer inspection, as here in the example of the Dutch criminal law for adolescents. Also, the fact that none of the new procedures for lie detection or risk assessment of criminals promised many years ago were able to gain acceptance received little attention. This raises the question of whether researchers are simply promising things here to attract scientific funding. The US MacArthur Foundation, in particular, has distinguished itself as a donor.

Partisan science?

Even the — now deceased — conservative Supreme Court judge Antonin Scalia (1936–2016), who opposed the majority opinion of Roper v. Simmons discussed above, pointed to a problematic pattern: The same scientific organizations, especially from the fields of medicine and psychology, which were opposed to the death penalty for juveniles and therefore attributed less responsibility to them, would have argued completely differently just a few years earlier. At that time, the issue was the permissibility of abortions on minors without parental consent. In the words of the high court judge:

“We don’t have to search long to find studies that contradict the court’s conclusions. As the plaintiff [i.e., the warden of the institution where Simmons was held, S. Schleim] pointed out, the American Psychological Association (APA), which claims in this case that persons under the age of 18 lack the capacity to take moral responsibility for their actions, had previously taken the exact opposite position before this court. In its opinion for Hodgson v. Minnesota, the APA found ‘rich scientific sources’ that would show that adolescents are mature enough to decide to have an abortion without parental involvement. The APA opinion cited psychological treatises and studies too numerous to list here and concluded: “In middle adolescence (14–15 years of age), young people develop skills of thinking about moral problems, understanding social rules and laws [and] thinking about interpersonal relationships and problems similar to those of adults.

Roper v. Simmons, Minority Opinion by A. Scalia. S. Phlegm

It is now known that researchers and university teachers, at least outside the law and theological faculties, tend to take liberal rather than conservative positions. But if, for example, the highest psychological association selects and interprets its studies by its liberal standpoint — here the extension of abortion, there the restriction of the death penalty — then it damages not only its credibility but the whole subject, perhaps even the whole of science.

Then we should not be surprised afterward if ever-larger sections of the population distrust scientific studies, for example on the safety or vaccinations or climate change. Because then they will have correctly recognized that researchers are also guided by their interests and thus pursue certain political goals. True is what is useful!

That is pure pragmatism. Such behavior is partly due, of course, to funding cuts, competition for funding, and careerism. With its independence of interests, however, science loses its special status and yet becomes just one opinion among many. Then researchers will no longer be able to demonstrate convincingly for evidence-based politics or the search for truth on the “Science Marches”. Then they should better write honestly on their signs: “Give us money!”

What remains of the new law?

All that remains is to assess the current crime situation in the Netherlands. As we have seen, the neuroscientific reasoning behind the new criminal law for adolescents was not correct at the back and the front. However, criminological, psychological, and sociological studies — and, last but not least, everyday experience — served as a basis for the decision. In the end, there is also a remnant of legislative arbitrariness, whether the limit for the mandatory application of adult criminal law is drawn at 21, 22, or only 23 years of age.

Incidentally, Dutch criminal defense lawyers criticize the unpredictability and inconsistency in the application of the new law. As I quoted above, this is at the discretion of the judge, “if he finds reasons for this in the personality of the offender or the circumstances of the crime”. In the absence of a brain test for accountability, one is guided by the personal appearance of a suspect as well as psychosocial factors such as whether the suspect still goes to school or still lives with his parents.

As jurist Eva Schmidt and her colleagues from Tilburg University state in a recent paper on the new law, the rules that have existed for decades on juvenile criminal law in the Netherlands are hardly ever applied to adults anyway. From just 1% of convictions in 2012, the rate would rise to 5% in 2016.

That is still very low by international standards. The increase is also due to the more frequent convictions of 18 to 20-year-olds, i.e. of all people, not the target group for whom the new law was passed. It seems that the initiative has simply reminded judges that convictions under juvenile criminal law are possible and sometimes desirable.

The balance sheet is mixed: politicians promise to be tougher in the election campaign, but they are pushing for a more educational approach in the legislative process. The whole thing is justified by neuroscientific studies that suggest the opposite. Representatives of the “new law” celebrate such events as examples of the special importance of brain research. In practice, however, the courts very rarely make use of the new possibilities and criticize lawyers for a certain arbitrariness.

Research Priorities

In 1981, the year in which brain researcher Roger Sperry was awarded the Nobel Prize, he wrote a change of priorities to his colleagues: neuroscientists should promise new applications to the public to receive sufficient attention and funding. His subject was of outstanding importance, he said, because: “Ideologies, philosophies, religious doctrines, world models, value systems and so on will stand or fall with the answers that brain research ultimately reveals. Everything comes together in the brain.”

Roger Sperry, transl. S. Phlegm

Forty years later, it seems that the researchers have kept to this. After the “decade of the brain” (the 1990s), large brain projects continued — until today. Neurological diseases such as Parkinson’s or Alzheimer’s naturally present society with challenges. But progress in treatment is extremely modest. Not only have none of the long-promised new psychotropic drugs been developed. The pharmaceutical industry has even largely abandoned psychiatric research due to poor prospects of success.

One should bear in mind that this neuro-research is always directed towards the future. Breakthroughs could then, of course, help many people. But if they fail to materialize, we will be left empty-handed. That is why we should take a multi-track approach and, for example, give more support to parts of the social sciences. These can already help people today to live with their problems — as best they can — in society.

About the Creator

AddictiveWritings

I’m a young creative writer and artist from Germany who has a fable for anything strange or odd.^^

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.