Captive in the Desert

Inside one of the 20th Century's greatest unsolved kidnappings

At around 5 pm on Wednesday, April 25, 1934, Fernando Robles was working at his electrical repair shop on Church Street in Tucson when a young boy entered the store and handed him a note.

“Strictly private information.

This is for the child’s father only.

Don’t tell wife or anyone else….”

Fernando must have at first thought this was someone’s bad idea of a prank. It was a ransom note demanding $15,000 in unmarked “20-10-5 bills” for the return of his daughter. But he quickly realized that the note was far too elaborate and violent to be a practical joke.

“You and your child will be killed -- if you tell any of this….”

“Your child will be killed if you don’t obey.”

The note was signed “X.Y.Z”

He handed the note to his wife, Helen, who read it with a growing sense of dread. Their daughter, June was a first-grader at the Roskruge School on 6th Street, about two miles from their home on Franklin Street -- too far and too dangerous a walk for a six-year-old. So June usually spent the afternoons with Fernando’s sister, Joaquina Kengla, who lived only two blocks from the school. Joaquina also babysat the couple’s three-year-old daughter, Sylvia, and Helen would swing by to pick both girls up after they closed up shop for the evening.

Helen picked up the phone and dialed her sister-in-law. Joaquina said June hadn’t been by. June usually walked home with her cousin, six-year-old Barney Kengla. Barney told Helen he didn’t know where she had gone.

The young parents paused for a moment. Then Fernando picked up the phone again, and called his twin brother, Assistant County Attorney Carlos Robles, to tell him June had been abducted.

SHE SEEMED TO BE SAYING ‘NO’

Within hours, law enforcement had pieced together the details of the afternoon.

At 3 pm, June and Barney were standing in front of the Roskruge School. Barney had a new model airplane and wanted to go home to play, and he was so distracted that he didn’t even notice that June was suddenly gone.

Around that same time, Marguerite Smith was picking up her son, and saw a beat-up Ford sedan pull up beside a little girl and beckon her towards the backseat. “The child seemed to be saying ‘no, no,’ but the man seemed to be insisting,” Smith said. Assuming it was a family matter, she simply drove on.

Two hours later, a boy named Goyo Estrada was walking on Church Street when a man called to him and offered him a quarter to take a letter into Robles Electric.

From the little girl’s mother and grandmother, they pulled together a description of little June: about three feet, six inches tall and “inclined to chubbiness,” she had brown hair cut in a bob and was dressed that day in a yellow dress with pink and green flowers and a pair of brown Oxford shoes. Her teachers, who hadn’t been monitoring the yard at the time of the kidnapping, said June was an extremely shy little girl and “has always been taught not to talk to strangers.” So if she was taken, it had to have been by force.

Hundreds of volunteers were soon organized into search parties to scour the city and suburbs and officers fanned out to check some of the hundreds of tips that had already begun pouring into the Pima County Sheriff’s Office. Customs and Border Patrol and the Arizona Highway Patrol were put on alert and the new Federal Bureau of Investigation offered their assistance as well. Carlos Robles even commandeered a small plane to search the surrounding desert.

But as night turned into day, there was no sign of June.

CHILDREN HAVE TO BE CAREFUL

“Children have to be careful, kidnappers might come out from a tree and get a child,” June had told her grandmother at breakfast the morning before her abduction.

Joaquina Robles later looked at this as a premonition, but it more likely a reflection of the fears around kidnapping in the early 1930s. Between the explosion in crime that accompanied Prohibition in the 1920s and the deepening crisis of the Great Depression, there were plenty of people venal enough or desperate enough to snatch an unwitting victim and hold him until the price was paid. The most sensational case, of course, was the abduction and murder of the infant son of Charles Lindbergh in March 1934; that crime remained unsolved in May of 1934.

Still, it was rare for a child as young as June to be abducted, and on the surface, Fernando and Helen Robles -- small business owners who lived with Fernando’s parents to get by -- were hardly the typical targets. “I don’t have $15,000 and I never did,” Fernando told reporters the day after the kidnapping. “And right now, there doesn’t seem any hope of getting the money.”

But Fernando was not the target of the ransom. Instead, it was his father, Bernabe Robles. A Tucson pioneer, Bernabe was reputedly one of the wealthiest men in the state. Arriving from Mexico as a child in 1865, he had gone on to make a small fortune as a cattle rancher and land developer.

This was confirmed the day after June’s disappearance when a letter was delivered to Bernabe bearing the same handwriting as the original ransom note.

“Child safe. We are willing to reduce the ransom to $10,000 if you act quickly. Child will be returned to you safely as per your instructions. Obey instructions. Signed, Z.”

PLEASE TAKE GOOD CARE OF MY BABY

Despite everyone’s best intentions, the Robles case soon spiraled into chaos.

Police patrols were everywhere and the roads in and out of town were blocked. Armed posses roamed the countryside. Homes and mailboxes were searched at random. The story was now international news, bringing a large press corps to the city, where they mixed with the large crowds that formed around the Robles home and published rumors that drummed up more hysteria.

And then there were the tips. “I never worked on a case in which we had so little authentic information,” Tucson Chief of Police Gus Wollard said on April 28. “We have run down clue after clue which has faded into nothing. Many of them have appeared good leads, none of them have produced tangible results.” Arrests were being made, but they were hoaxers calling in fake leads, not valid suspects.

Fernando felt events slipping far out of his control. He was having a hard time assembling all the money. Helen was so hysterical that he feared she was going to have to be hospitalized. The crowds, the cameras, the patrols -- all this activity was likely to spook the kidnappers and keep June out of his reach.

With Carlos acting as the family spokesmen, Fernando asked for the search to be called off on April 28. Two days later, he penned a letter to the kidnappers and asked the Tucson papers to print it in full.

“I am ready and willing to follow faithfully any and all instructions received by me so that my little girl, June, will be returned safely and unharmed….”

He said he had asked all law enforcement officers to withdraw from the search and take down the roadblocks and that all rewards be suspended.

In return, he asked for proof of life. He wanted them to send him a scrap of her dress and the answer to four very specific questions:

What do you do with your bunnies in the morning? What do you call Corney? What is the name of Bettina’s maid?Where is your little box with the key in it?

“Please,” he said in closing, “take good care of my baby.”

A DESPERATE RITUAL

Night after night, Fernando followed the same desperate routine. At 9:00, he would drive from his Franklin Street home to Main, then onto Speedway, and finally into the dark desert east of the city. The instructions in the ransom note were explicit: be on Old Wetmore Road at 9:30….be on Country Club Road by 9:45...be on 6th Avenue at 10:20….

Fernando was never sure what would happen, if he would find his little girl wandering along a quiet country road or if her captors were laying in wait to seize him as well. Night after night, neither happened, and he would return to the city drained by the ritual. He was seen by reporters late one night, dressed in overalls and a leather jacket, walking from cafe to cafe asking patrons if they had seen his brother Carlos. Asked for comment, he wearily waved them off before wandering off, flashlight in hand.

The perpetrators remained worryingly silent. As the days went by with no sign of June or decent leads, the newspapers helpfully pointed out that in almost two dozen known kidnappings in recent years, it had taken a month or more to negotiate a release, and victims were almost always returned unharmed. Even in the Lindbergh case, it seemed clear that the baby had been killed by accident, rather than intent. This was, however, cold comfort for Fernando and Helen, now facing the start of a third week with no sign of June.

NOW OR NEVER

Carlos Robles thought they would find the little girl dead.

Monday, May 14 started with the discovery of a note shoved under the office door of his boss, County Attorney Clarence Houston. A janitor found it under the door when he arrived to clean that morning and immediately turned it over to the sheriff. When the sheriff handed it to Carlos, the young attorney had turned pale.

‘Z’ answered all four questions from Fernando’s April 30th letter correctly. But the tone of the two-page letter was not encouraging: the writer was growing angry and paranoid.

“Now if you play dirty, we will be dirty. Your child is O.K. Deliver money as told you to be alone and drive slow keep spies away. Why don’t you do as told? You will never get child until you do as we say. We are ready when you are. You have tried to trap us. We know what you have done…”

He also complained that Fernando was failing to use a car with no doors as they had ordered, and should just “stay home” if he wasn’t going to follow instructions.

It was signed: “Now or never. X.Y.Z OBEY.”

Then, later that morning, Arizona Highway Patrolman Riley Bryan arrived from Phoenix with a postcard which had been found in the morning mail of Governor BB Moeur. Postmarked from Chicago on May 10, it said simply:

Go E. on Rincon Way one mile till the road cease to be straight. Then ¼ mile east then 150 steps N. You will find the body covered with a load of cactus. X Y Z OBEY.”

Robles and Clarence Houston decided to go alone. They figured -- at best -- this was another false lead. At worst, they would find “the body” in the desert. Together, they walked through the cactus and mesquite, finding nothing. Eventually, they split up to cover more ground.

After a half and hour of searching alone, Carlos was on the verge of despair. He was about to turn around when he saw a cactus off in the distance that formed a perfect cross. “I gave me courage and strength to go forward,” he said. “It gave me hope.”

A moment later, he suddenly heard Houston yell, “Carlos! É Carlos!”

“For a time I could not find him, the underbrush was so thick, and then I saw his white shirt. I ran. From a distance, I saw him lean over and pick up a bundle apparently off the ground. I was sure June was dead. When I saw she was alive, I could not believe my eyes or restrain myself.”

“Uncle Lichi!” she called out, using her nickname for him.

Then he knew this was real. He clutched her to his chest and fell to the ground, sobbing.

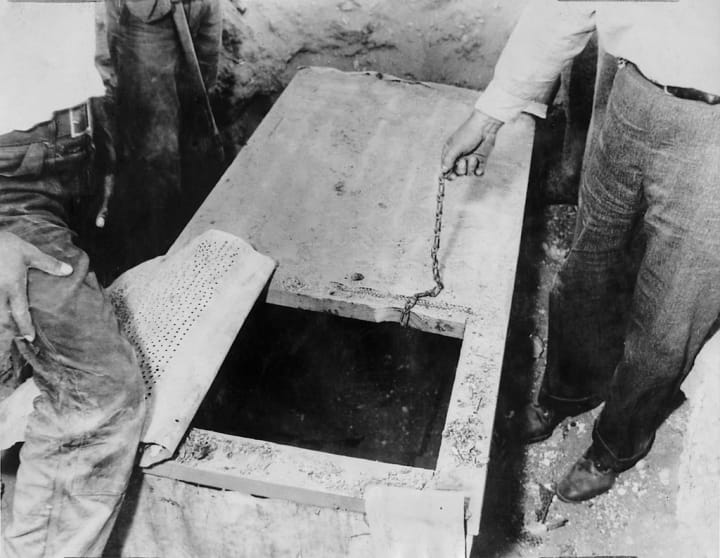

Clarence Houston had almost missed her. He had just happened to see what appeared to be a perforated metal square on the desert floor, half obscured by cactus. He pushed the cactus aside and pulled back the metal -- only to see June Robles looking up at him from the bottom of a narrow dugout, her small ankle cuffed to a chain secured to a post.

“Hello, June,” he said very softly, so as not to scare her. “Do you know me? Are you afraid of me?”

She looked up, dazed by the sudden light. “No,” she said. “I’m not afraid of you.”

Looking around, he spied a key hanging on a nearby cactus. On a hunch, he tried it on the shackles on her leg and lifted her out of this ‘living tomb,’ just as Carlos arrived. June was so weak she could barely stand; she was filthy and covered in heat rash. Clearly traumatized, she couldn’t answer many questions and they didn’t want to press her, but what they did realize is that she had been in that hole -- covered with vermin, surrounded by rotting food, with a pail for a toilet, chained to a post -- for the past nineteen days.

As they prepared to carry her back to the car and take her home to her parents, she held back. “I want my report card,” she told them. “I want to show it to Mamma. I got two ‘1s’ and need to show it to her.” So they went back to the hole and retrieved it for her.

BRUTES, THEY MUST BE

Examined by her doctor later that evening, June turned out to be in relatively good physical condition. Aside from the heat rash, she had sores on her ankles from the shackles and a burn on her forehead where it touched the scalding metal roof of the dugout. Those wounds would heal.

It was her emotional condition that was more concerning. She accepted the hugs and kisses from her overjoyed parents and grandparents; she spent some time playing with her bunnies and her paperdolls; she gamely posed for reporters and let her father carry her onto the front porch to greet some of the 200 well-wishers that crowded the streets; but she remained quiet and listless for several days following her return home.

She remembered few details from the previous weeks. She had been in front of her school when a strange man told her he was taking her to her daddy and made her get in the car. Then they were in the country, and he chained her up and put her in the hole and covered her up. There were two men, named “Will” and “Bill,” and they would come to bring her water and bread with jam and cookies and take away her waste pail. They told her they would whip her and stab her with a knife if she cried. Sometimes the men didn’t come for days. She made dolls out of little sticks and bits of trash in the hole to pass the time. There were scary noises outside at night, so she slept during the day. She missed her momma and her daddy and her sister and her bunnies. She was worried something bad had happened to Barney. Time lost meaning.

Her grandmother, Joaquina, joined the throngs of sightseers who went out to see the six-foot by two-foot hole in the desert. “It is so lonely,” she told the reporter who accompanied her. If it had rained, mia nina might have drowned. Snakes at night and coyotes howling! Ah! She was brave in such loneliness! There are no houses, see, for many miles. She might have died alone.”

“I am sure they believed she was dead or they would not have sent the note. At first, I thought one of them had a tenderer heart than the others, but now I know. It was not tenderness of heart, but certainty she was dead. Brutes, they must be.”

They spent a few more moments contemplating the scene. “Let us go,” she said. “The heat, the people, the loneliness I feel here makes my heart sad. I wish to go back to my June so my arms know she is safe.”

THE WAY IT WAS MEANT TO BE

Inevitably, there were questions. Could June really have survived 19 days in a pit in the searing desert heat with so little injury? Maybe she was only held there for a short time? Why could she not clearly identify her captors? Was the random paid or not? How was it that Carlos Robles and Clarence Houston had found her with no help from the police and no witnesses? Wasn’t that a bit convenient?

This speculation only increased when it was reported that Fernando was close to signing June to a lucrative vaudeville or motion picture contract where she would recreate her ordeal for stage and screen. Fernando told the press that this was in part to educate other parents on the dangers of kidnappers. He vowed to put aside $1500 for the arrest of his daughter’s attackers.

Law enforcement, who had access to all the case material, did not doubt June’s story. It was clear from the evidence collected on the scene that she had been in the pit for a long time and might well have died down there had too many more days passed.

But that’s all they knew. June flipped through hundreds of mugshots at “Uncle Lichi’s” office and never identified her captors. A couple of stray fingerprints turned up no suspects. A man who ran a Tucson dance hall was found to have handwriting similar to the ransom note, but the case against him later fell apart. State and Federal investigators would spend 32 months on the case and ended up knowing little more at the end then they had at the beginning.

In December 1936, a grand jury in Tucson called June's ordeal an “alleged kidnapping” said the case file should be closed. One of the most famous kidnappings in American history would go unsolved.

The Robles had long since retreated from public view. June never joined the vaudeville circuit or made a movie. She never returned to the Roskruge School, and spent the remainder of her education at the private Immaculate Heart Academy. Her last comment to the press came in 1936, when she said she wanted a quiet life and “to be a mother like my mother.” She married another Tucson native, Dancey “Dan” Birt, in July 1950 and the couple had four children.

The Robles were exceptionally long-lived. Barnabe died in 1945 at age 87 and Joaquina in 1950 at 82. Fernando and Helen were married for nearly 70 years and both died in 1993, aged 88 and 87, respectively. June herself lived a full eight decades beyond her ordeal in the desert, passing away in September 2014 at 87.

Keeping her desire for privacy, the family ran a small obituary without mentioning her maiden name. The national media didn’t learn of her passing until October 2017.

“That was the way she wanted it,” her son James Birt said in a brief telephone interview with the New York Times. “That was the way she wished it. That was the way it was meant to be.”

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.