Beyond the Blue Chip Stamps

inspiration ====> opportunity

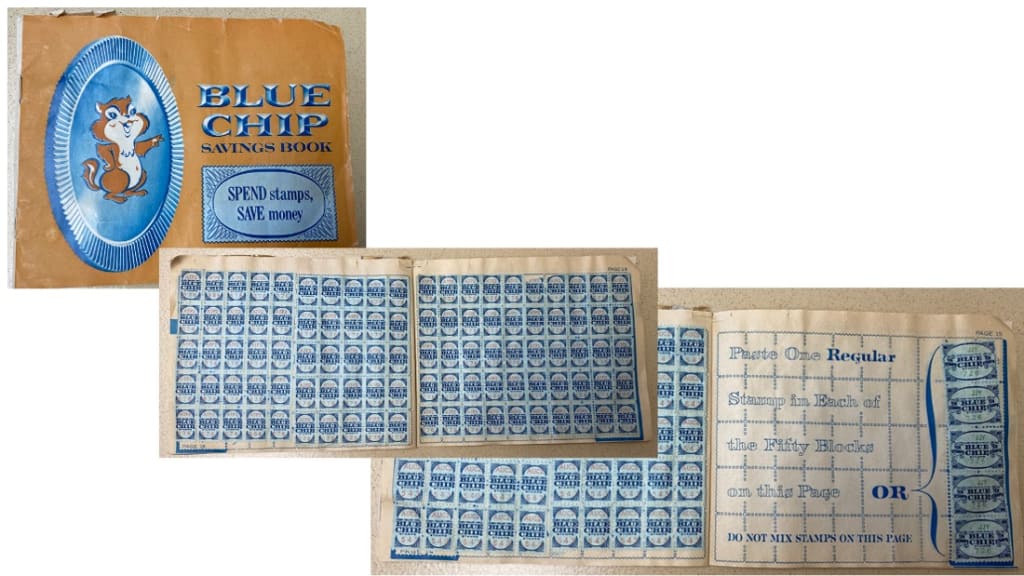

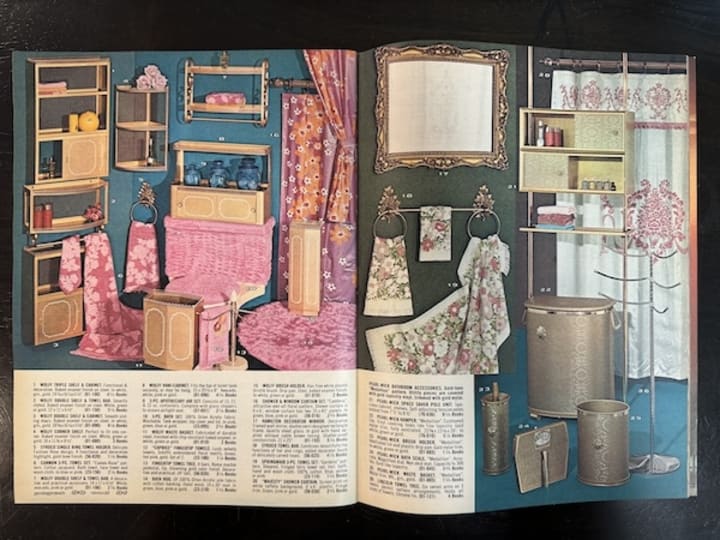

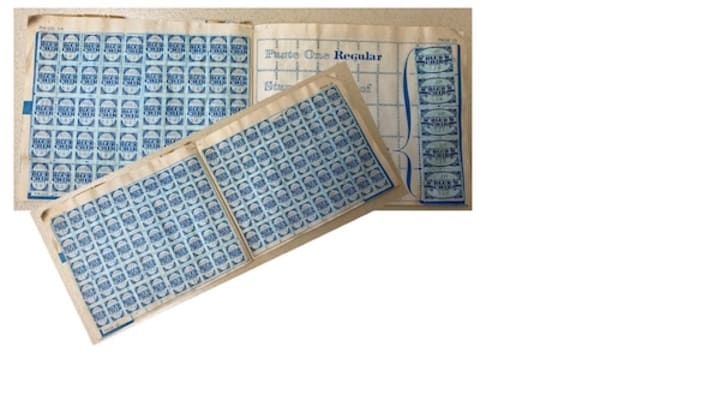

It was the 1960’s. My three sisters and I would sit at the kitchen table, all talking at once with animated excitement, while we sponged and pasted piles of Blue Chip stamps into newsprint booklets. With the dried, crunchy pages on the left, and new empty pages on the right, each booklet promised that we could buy anything our hearts desired — as long as it was in the Blue Chip Stamp Catalog. The Catalog was our dream book, our book of toys, games and kitchen appliances, housewares and electronics. All those non-necessities were impossible to consider with our frayed family finances. But with Blue Chip stamps as our currency, we were feeling rich in our tiny 2-bedroom west Berkeley apartment. We could go down to the Redemption Store in Oakland to buy anything in the Catalog, if we saved for long enough.

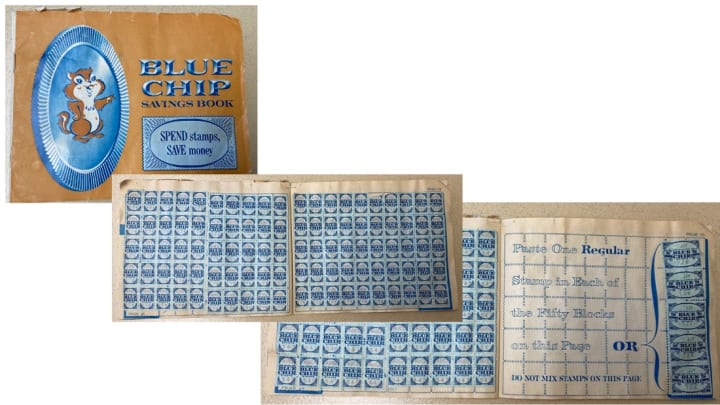

How about a blender to make our own milkshakes? 6 books! If we had the blender, maybe Ma would let us buy a quart of ice cream. How about getting colorful bedspreads for our twin-size bunkbeds? 7 books each! We slept compactly— an older sister and a younger sister in each bed, with one head at the top and one head at the bottom. How about a sewing machine to make our own clothes? 41 books! Then our older cousins could teach us to make outfits from sewing patterns, like they did, if we could buy some fabric. Kids at our school had things at home that we didn’t have, but if we saved up enough Blue Chip stamps we could have those things too. It seemed like everybody on TV had things in their homes that we didn’t have, but we were working those Blue Chip stamps like nobody’s business.

Every trip to the Berkeley Co-op grocery store and the Union 76 gas station created Blue Chip currency for our family. Using a bulky dispenser next to their cash register, the cashier would dial out a long thread of perforated stamps representing something like 1/10 of the dollar amount we spent at that store.

We had an entire drawer in our kitchen dedicated to Blue Chip stamps — the filled booklets with stiff gummy pages of 50 singles and super-ritzy pages of “five tens”. The drawer also held the Catalog and empty booklets, representing our dreams of items we wanted to own. The drawer held any loose stamps that hadn’t been glued into a booklet yet, but in our home those were never loose for very long. We even kept a small sponge in that drawer, dedicated to moistening the Blue Chip stamps ever since that time our youngest sister threw-up after licking too many singles in one evening. In the world of Blue Chip stamps, we had currency.

I remember our animated stamp-pasting discussions at the kitchen table. KDIA “Lucky 13” was always our background soundtrack on the radio (yes, bought with Blue Chip stamps), blending soulful harmonies into our aspirational dialogue. If we saved up enough stamps, could we buy a car?!! If we bought the set of matching green suitcases, would we get to go on a trip?! Our stamp-pasting was lively, as we swapped 1-point and 10-point stamps around our kitchen table, along with the sponge, filling in the designated squares on the damp pages in the booklets.

While we debated and daydreamed about possible items we wanted to buy with our Blue Chip stamps, Ma steered our conversations toward possible futures for ourselves. Blue Chip stamps made the impossible possible for buying stuff, but Ma pointed out that stuff would come and go, stuff was not so important, stuff would break and eventually end up in a trash can. Education, on the other hand, lasted a lifetime. Education made the impossible possible for careers with good-paying jobs. Ma emphasized that once we had education, nothing and no one could ever take it away. Education was key.

“You can be whatever you want to be,” Ma would say to the four of us all the time. “Just go to school and learn about whatever you’re interested in. Read some books. God’s going to open doors for you, so be ready with your education.” We were little Black girls, growing up in west Berkeley, California. Our mother, divorced from our father, had a high school education from rural Louisiana. She was our role model for persistence, tenacity, faith, and finding resourceful ways to make the impossible possible. Ma had negotiated for all four of us to attend St Joseph’s Catholic Elementary School for $10 in monthly tuition. Not $10 each, but $10 for all four of us. Ma was buying our groceries and paying St. Joe’s tuition with tip money from her morning waitressing job at a diner. She was paying rent and utilities from her evening and Saturday job as a liquor store cashier.

* * * * * * * * * *

Our oldest sister was in charge of taking all of us to the small branch of the Berkeley Public Library on University Avenue, every other Saturday. I loved that library and I read everything the librarians suggested. But … the actual university that University Avenue was named for, located in the part of town where other people went … but where we never went? Nobody was talking to us about that educational resource. We vaguely knew there was a college, but we never thought it had anything to do with us. The University of California was a few miles away from our apartment, but impossibly far from our world.

In my world, I sponged Blue Chip stamps with my sisters to buy curtains for our tiny apartment, and I daydreamed about NASA. I watched every Apollo launch that was televised — riveted to the TV during the Apollo 11 moon landing and the Apollo 13 recovery mission. I imagined myself in that Houston Mission Control room, operating those computers and making calculations that helped astronauts survive. I never saw Black people or women in the televised Mission Control rooms, and I wondered why. I asked Ma and she told me, “Education, chère. Anything you want to learn, you can learn it. If all those men learned it, you can learn it.” I would move our thin curtains aside to stare at the moon, imagining what it felt like to discover new knowledge in space.

* * * * * * * * * *

When I reached high school in the 1970’s, going strong as a straight-A student, I enthusiastically joined a student group that was formed to introduce Black, Hispanic, and Native American teens to careers in engineering and science. There, I found my fellow emerging nerds, my people. And these people were all talking about going to college to become engineers or scientists, astronauts, medical doctors, computer programmers … they didn’t seem to think this was impossible. I spent a lot of time considering the impossible and the possible. College cost a lot of money — impossible. But a part-time job and scholarships were a form of currency to pay for it — possible. Girls didn’t become engineers or scientists — impossible. But my mother said I could be anything I wanted to be — possible.

At the end of our sophomore year, our student group went on a field trip to the University of California. Our school bus drove east on University Avenue until the bustling street ended … at the university! Connections started linking up in my mind. On campus, we met college students (I noticed that none were Black people); toured a dorm (no Black people); ate in a dining hall (Black people were serving the food); and visited several intriguing engineering laboratories (no Black people there, and, yes, we heard the tour guide the first 20 times he told us not to touch anything). Further connections were linking up in my mind, along with new questions and some kind of attitude. Then we were introduced to two male professors — one was Black and one was Hispanic. They talked about the importance of a college education. They answered questions about choosing careers that were interesting. They kept it real with facts about discrimination and obstacles. They encouraged us to seek out scholarships. Then they brought it all together by acknowledging that we needed to become the representation we were not seeing on campus that day. Now connections were linking up with blazing speed. Is there a library, I asked? Yes, they said, and we all took a walk through the reading rooms and stacks of Doe Memorial Library. My jaw dropped. I think my heart skipped some beats. THIS was a library. I could learn anything here. I could learn EVERYTHING here! On the bus ride home, my emotions were on a roller coaster. Could I really go to college here? Could I become an engineer? Was it possible or impossible?

* * * * * * * * * *

I decided to level-up my own library game, from the small branch library to the (relatively) huge main Berkeley Public Library on the corner of Shattuck & Kittredge. It was time to get help from the librarians. There were four reference librarians there, that summer, and they seemed very glad to educate me. They introduced me to resources about college, such as books to prepare for the SAT, and a file cabinet with hundreds of colorful printed college catalogs (but there were no Black people in those PWI college catalogs, and I didn’t learn about HBCUs until years later). I remember the day when one of the librarians showed me the College Blue Book of Scholarships. Oh, a gold mine! Better than a gold mine, it was written specifically for people who intensely wanted to go to college but needed some help paying for it. That was me, waving my hand in the air.

During my junior year, I put together a detailed plan to apply for every scholarship in the College Blue Book for which I was eligible — I was not playing. I started requesting letters of recommendation from my high school teachers, making 5-cent photocopies so I could use the letters for college applications and scholarship applications. I also got an after-school job at a fast-food place. Workers on the closing shift were paid more than on the other shifts because we were responsible for mopping the floors and cleaning the bathrooms. I signed up for a lot of those closing shifts. An engineering career was looking better and better.

Armed with office supplies from the Blue Chip Stamp Catalog, and postage stamps purchased with my fast-food paychecks, during my senior year of high school I went after the impossible goal to gather up enough funding for my first year of college. I methodically applied for over 100 scholarships. Eventually, I received letters from about 20 organizations; each awarded me a scholarship ranging from $100 to $1000. Along with my fast-food job savings, those scholarships added up to enough for my first year of college tuition, books (mind-blowingly expensive!), dorm room, meal plan, a typewriter and school supplies. A few were recurring scholarships for years two through four. When my admission letter arrived from the UC Berkeley College of Engineering, it all came together — the impossible was now possible. God was opening doors, and I was going to college.

My family encouraged me one hundred percent. With our Blue Chip stamps, we bought that set of green luggage — not for a vacation, but for me to move into the dorms. With our Blue Chip stamps, we bought a set of twin-size sheets, a bedspread and a pillow for my dorm bed. Those familiar stamps provided an alarm clock for me, a portable hair dryer, and one set of towels. And, most importantly, that September my family dropped me off at the college dorm with all the love in the world. Ma told me how proud she was that I was going to get my education and become an engineer.

With Blue Chip stamps, I had dreamed about the possibility of buying stuff we couldn’t otherwise afford. But Ma was absolutely right. It wasn’t about stuff, it was about inspiration. God opened doors, education was key, and the possibilities before me were about becoming the person I wanted to be.

* * * * * * * * * *

I was (and am) grateful to the folks who helped make the impossible possible for me. My family, including the ancestors who went before me. Friends and neighbors. Educators and librarians. Generous people who provided scholarships to passionate kids. Authors who wrote the thousands of books from which I’ve learned so much fact and fiction. The Blue Chip Stamp people, who developed a business model that gave inspiration. And my number one ace: God.

The work at UC Berkeley was exciting, and it was also hard. Nonetheless, four long years later, I emerged with a new type of currency: a bachelor’s degree in Electrical Engineering and Computer Science from UC Berkeley. I was ready to gooooo!

©2024. Luksi Bayou. All rights reserved.

About the Creator

Luksi Bayou

Luksi Bayou (she/her) writes fiction inspired by lived experiences. Sometimes she also writes about data. More stories on Medium: https://tinyurl.com/ys27mm7x

Enjoyed the story? Support the Creator.

Subscribe for free to receive all their stories in your feed. You could also pledge your support or give them a one-off tip, letting them know you appreciate their work.

Comments (2)

Such a great story Luksi. It sounded like a daunting dream, but perseverance and a positive attitude, combined with a loving family came through for you. Well earned pride in your achievements. Upwards and onwards.

Interesting and delicious content. Keep posting more