Bastille, the story of a revolution

A people pushed too far.

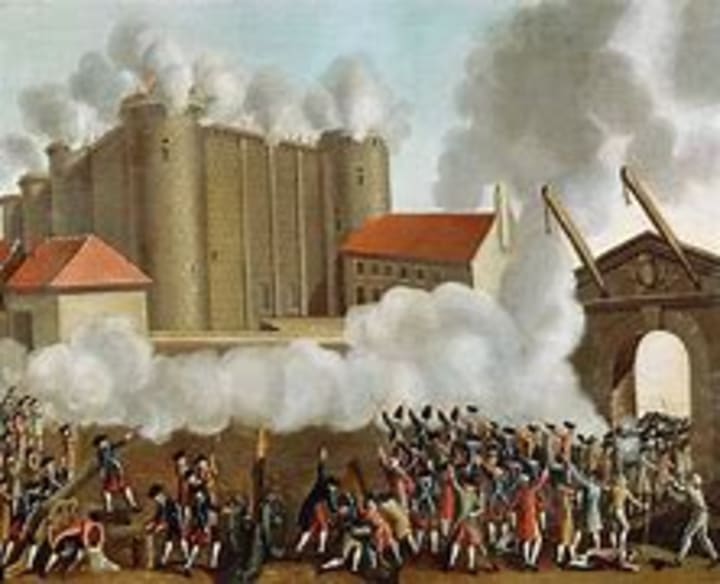

The Storming of the Bastille occurred in Paris, France, on 14 July 1789, when revolutionary insurgents stormed and seized control of the medieval armory, fortress, and political prison known as the Bastille. At the time, the Bastille represented royal authority in the center of Paris. The prison contained only seven inmates at the time of its storming, but was seen by the revolutionaries as a symbol of the monarchy's abuse of power; its fall was the flashpoint of the French Revolution.

Disseminating the story within the art

It is 1789. The reign of Louis XVI of France is facing a major economic crisis. This crisis was caused in part by the cost of intervening in the American Revolution and exacerbated by a regressive system of taxation, as well as poor harvests in the late 1780s. The poor, the 'commoners', as they were called, are fed up with paying the cost of their leader's lavish lifestyle, and reckless support of a war which only added to the plight of the poor.

France, which had been a long time rival of Great Britain had secretly shipped supplies to the Americans in 1776. This further antagonized the wrath of the people, along with taxation and poor harvests.

Even though France had extreme financial problems, the king's new representative spent lavishly, rationalizing that this would make France appear wealthy. This only further added to the woes of the country.

The increasing unpopularity of the new queen, Marie Antoinette in the final years before the outbreak of the French Revolution also likely influenced many to attribute their suffering, in part to her. During her marriage to Louis XVI, her critics often cited her perceived frivolousness and very real extravagance as factors that significantly worsened France's dire financial straits.

A National Assembly, drawn from the commoners had been formed.

Parisan society was close to insurrection and in François Mignet's words, "intoxicated with liberty and enthusiasm", they showed wide support for the Assembly. The press published the Assembly's debates; political debate spread beyond the Assembly itself into the public squares and halls of the capital. The Palais-Royal and its grounds became the site of an ongoing meeting.

The crowd, on the authority of the meeting at the Palais-Royal, broke open the prisons of the Abbaye to release some grenadiers of the French guards, reportedly imprisoned for refusing to fire on the people. The Assembly recommended the imprisoned guardsmen to the clemency of the king; they returned to prison for a token one-day period and received a pardon. The rank and file of the regiment, previously considered reliable, now leaned toward the popular cause.

On 11 July 1789, Louis XVI—acting under the influence of the conservative nobles of his privy council—dismissed and banished his finance minister, Jacques Necker (who had been sympathetic to the commoners) and completely reconstituted the ministry.

News of Necker's dismissal reached Paris on the afternoon of Sunday, 12 July. The Parisians generally presumed that the dismissal marked the start of a coup by conservative elements. Liberal Parisians were further enraged by the fear that a concentration of Royal troops—brought in from frontier garrisons to Versailles, and other areas, would attempt to shut down the National Constituent Assembly, which was meeting in Versailles.

Crowds gathered throughout Paris, including more than ten thousand at the Palais-Royal. Camille Desmoulins successfully rallied the crowd by "mounting a table, pistol in hand, exclaiming: 'Citizens, there is no time to lose; the dismissal of Necker is the knell of a Saint Bartholomew for patriots! This very night all the Swiss and German battalions will leave the Champ de Mars to massacre us all; one resource is left; to take arms"!

During the public demonstrations that started on 12 July, the multitude displayed busts of Necker and of Louis Philippe II, Duke of Orléans, then marched from the Palais Royal through the theater district before continuing westward along the boulevards. The crowd clashed with the Royal German Cavalry Regiment. From atop the Champs-Élysées, Charles Eugene, Prince of Lambesc, unleashed a cavalry charge that dispersed the remaining protesters at the Place de la Concorde. The Royal commander, Baron de Besenval, fearing the results of a blood bath amongst the poorly armed crowds or defections among his own men, then withdrew the cavalry.

Meanwhile, unrest was growing among the people of Paris who expressed their hostility against state authorities by attacking customs posts blamed for causing increased food and wine prices. The people of Paris started to plunder any place where food, guns, and supplies might be hoarded. That night, rumors spread that supplies were hoarded at Saint-Lazare, a huge property of the clergy, which functioned as a convent, hospital, school, and even a jail. An angry mob broke in and plundered the property, seizing 52 wagons of wheat, which were taken to the public market. That same day multitudes of people plundered many other places including weapon arsenals. Royal troops did nothing to stop the spreading of social chaos in Paris during those days.

The regiment of French Guards formed the permanent garrison of Paris and, with many local ties, was favorably disposed towards the popular cause. This regiment had remained confined to its barracks during the initial stages of the mid-July disturbances. With Paris becoming the scene of a general riot, Charles Eugene, not trusting the regiment to obey his order, posted sixty dragoons to station themselves before its depot in the Chaussée d'Antin. The officers of the French Guards made ineffectual attempts to rally their men.

The rebellious citizenry had now acquired a trained military contingent. As word of this spread, the commanders of the royal forces encamped on the Champ de Mars became doubtful of the dependability of even the foreign regiments.

The crowd gathered outside the fortress around mid-morning, calling for the pulling back of the seemingly threatening cannon from the embrasures of the towers and walls, and the release of the arms and gunpowder stored inside. Two representatives from the municipal authorities from the Town Hall, were invited into the fortress and negotiations began, while another was admitted around noon with definite demands. The negotiations dragged on while the crowd grew and became impatient. Around 1:30 pm, the crowd surged into the undefended outer courtyard.

A small party climbed onto the roof of a building next to the gate to the inner courtyard of the fortress and broke the chains on the drawbridge, crushing one person as it fell. Soldiers of the garrison called to the people to withdraw, but amid the noise and confusion these shouts were misinterpreted as encouragement to enter. Gunfire began, apparently spontaneously, turning the crowd into a mob. The crowd seems to have felt that they had been intentionally drawn into a trap and the fighting became more violent and intense, while attempts by deputies to organise a cease-fire were ignored by the attackers.

The firing continued, and after 3:00 pm, the attackers were reinforced by mutinous gardes françaises, along with two cannons each of which was reportedly fired about six times. A substantial force of Royal Army troops encamped on the Champ de Mars did not intervene. With the possibility of mutual carnage suddenly apparent, Governor de Launay ordered the garrison to cease firing at 5:00 pm. A letter written by de Launay offering surrender but threatening to explode the powder stocks held if the garrison were not permitted to evacuate the fortress unharmed, was handed out to the besiegers through a gap in the inner gate. His demands were not met, but Launay nonetheless capitulated, as he realized that with limited food stocks and no water supply, his troops could not hold out much longer. He accordingly opened the gates, and the victors swept in to take over the fortress at 5:30 pm.

Ninety-eight attackers and one defender had died in the actual fighting or subsequently from wounds, a disparity accounted for by the protection provided to the garrison by the fortress walls. Launay (the governor) was seized and dragged towards the Hôtel de Ville in a storm of abuse. Outside the Hôtel, a discussion as to his fate began. The badly beaten Launay shouted "Enough! Let me die", and kicked a pastry cook named Dulait in the groin. Launay was then stabbed repeatedly and died. An English traveler, Doctor Edward Rigby, reported what he saw, "We perceived two bloody heads raised on pikes, which were said to be the heads of the Marquis de Launay, Governor of the Bastille, and of Monsieur Flesselles, Prévôt des Marchands. It was a chilling and a horrid sight! ... Shocked and disgusted at this scene, we retired immediately from the streets.

Three members of the garrison were lynched plus possibly two of the Swiss regulars.

Many members of the royal families met tragic ends during the French Revolution. Some would face the guillotine, while others were destined to die in prison or poverty.

King Louis XVI of France was executed by guillotine on January 21, 1793, after being caught trying to escape with his family during the explosion of the French Revolution. Marie Antoinette was guillotined in 1793 after the Revolutionary Tribunal found her guilty of crimes against the state.

The famous saying "Let them eat cake", which is alleged to have been said by Marie when told that the 'commoners' were hungry, has not been proven to have occurred.

About the Creator

Novel Allen

Clouds come floating into my life, no longer to carry rain or usher storm, but to add color to my sunset sky. ~~ Rabindranath Tagore~~

Enjoyed the story? Support the Creator.

Subscribe for free to receive all their stories in your feed. You could also pledge your support or give them a one-off tip, letting them know you appreciate their work.

Reader insights

Outstanding

Excellent work. Looking forward to reading more!

Top insights

Compelling and original writing

Creative use of language & vocab

Easy to read and follow

Well-structured & engaging content

Excellent storytelling

Original narrative & well developed characters

Expert insights and opinions

Arguments were carefully researched and presented

Eye opening

Niche topic & fresh perspectives

Heartfelt and relatable

The story invoked strong personal emotions

On-point and relevant

Writing reflected the title & theme

Comments (4)

This was so fascinating! I had no idea about any of these events!

Despite the horrors that come to mind regarding any war, I must admire the eloquence of "'Citizens, there is no time to lose; the dismissal of Necker is the knell of a Saint Bartholomew for patriots!" This article was very well done. Are you a history teacher?

very good.you are a great writer.may you achieve what you want.

Thank you for sharing this, lots of details here I wasn't aware of. Very interesting 😁