This Is The Fascinating History Of The London Underground

The Thames Tunnel was the very first tunnel in the world to be constructed under a river, and it was described as the eighth Wonder of the World.

As a response to the city's rapid growth during the 19th Century, the world's first underground railway, the London Underground was created. With 1.379 billion passengers using it, the London underground is the 11th-busiest tube system on the planet. The tunnels stretch across London for 249 miles, often overlapping and offering travellers plenty of options to move from one location to another. The Underground history, its tunnels, and the people connected to it is genuinely fascinating. We hope that reading this article, and you'll immerse yourself in the past and lore and find out more than you know about the Tube.

The first steam railway began in 1825.

And 25 years later, King's Cross had become a terminus for steam trains arriving in London. The railways were not permitted to expand any further into the city, leaving 750,000 workers coming to the capital each day to find a way to get to work in the heart of town. That inevitably led to gridlock.

One hundred fifty years ago, London was grinding into a halt. It needed an ambitious solution to link the main railway stations to the city centre. There was only one way to go, and that was underground.

It is important to remember that for many people, the thought of going underground and travelling underground at speed was a very novel concept. Many Victorian writers saw death, doom and destruction to people travelling on underground railways.

Newspapers, such as The Times, ran a fierce campaign against the railway. Even if it worked, it would never pay because people would never use it. They were speculating about underground passages soaked with sewage drippings and infested by rats.

From 1825 to 1843, Isambard Kingdom Brunel and Thomas Cochrane created the tunnelling technology to construct the Thames Tunnel, enabling the transport of people and goods under the river Thames and further connecting the two sides of the two sides the city.

Around the same period, City Solicitor Charles Pearson argued for an underground transport system and gave support to several schemes to build one. He knew that if people could easily get in and out of the city centre, people could live further away, and the slams would be a thing of the past.

However, in 1846, the Royal Commission rejected his plan.

In 1852 Pearson again campaigned for the underground railway, and this time he had moderate success with the organisation of the City Terminus Company, which ran a railway line between Farrington and King's Cross. Unfortunately, although the scheme had the city's support, the railway companies were not interested, and that would be until the North Metropolitan Railway was built.

The impetus behind the construction of the Met was the Bayswater, Paddington, and Holborn Bridge Railway Company, which linked the Great Western Railway at King's Cross to the rail line of the City Terminus Company, which the railway company had bought.

Attempts by the organisation to bring a bill through Parliament were often met with resistance until 1854 when Royal Assent was finally given.

By that point, the organisation changed its name to the Metropolitan Railway and planning were extended to include the London and North Western Railway as well as the Great Northern Railway.

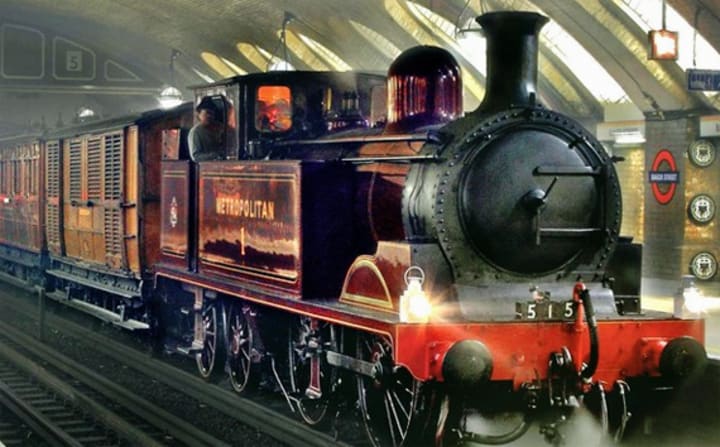

The Metropolitan Railway first opened in 1863.

It connected the three major terminals at Paddington, Euston and King's Cross with the centre of the city at Farringdon.

The initial suggestion by Metropolitan railways engineer, John Fowler, had been to have a new underground railway running on compressed air. Not steam. The idea was the trains would be blown through tunnels and sucked back by air generated in great compressors air each end of the line. But the system had a significant flaw. The compressed air leaked continuously through the tunnel joints.

The Metropolitan Railway was forced to borrow steam locomotives and rolling stock from the Great Western Railway to start its service. A revolutionary idea and immediate success. It carried 38,000 people on its first day. The timetable ran between 8 am and 8 pm with a train every 15 minutes. The time for the 3 and 3/4 mile journey from Paddington to Farrington was 18 minutes. It was stopping at all stations, which was not much slower than today.

When the Metropolitan and the Great Western Railway fell out, the Metropolitan had to supply its rolling stock, and for this, they turned to the engineering company Bayer Peacock. The original carriages were divided according to class. The fares charged was according to who travelled. The first class was for top city professionals moving from their fashionable west London houses. The second class was for management and Clarks. The third was for everybody else (who would have travelled quite uncomfortably in cramped spaces.

In the first year, a total of 9.5 million people used the new transport system. That number increased to 12 million the year after.

The great success meant that many new companies asked Parliament for new underground railways. The District Railway followed. Eventually, the two networks together will form the foundation of the Circle Line as well as sections of the Piccadilly Line and the District Line. The rivalry between the owners of the two railways, James Forbes and Edward Watkin, meant that the joining phase of the two took twenty years, and the lines continued to encounter problems until the railways were merged in 1933.

Over the next few decades, other lines would form from the various railway companies. That included the Hammersmith & City Line (built out of the Metropolitan Railway), the Northern Railway (constructed by the City and South London Railway as well as Charing Cross, Euston, and Hampstead Railway), and the Waterloo & City Line (established by the London and South Western Railway).

Successively, steam engines began to give way to electric railways, although some steam engines would continue to be used even in the 1960s.

The Underground Electric Railways Company of London, founded in 1902 by American transport mogul Charles Tyson Yerkes, provided power for many of the electric railways. Digging technology also improved to enable tunnels even deeper than those sub-surface lines that were first built.

Metropolitan and District Railway lines were created mostly by digging trenches and placing a roof over them, and the Northern Railway, which opened in 1890, was the first technically underground one. The line went from Stockwell to King William Street, and then Moorgate, Euston, and Clapham Common. Meanwhile, the Hampstead Tube was built by CCE & HR, and by the late 1920s, the two integrated into what we know as the Northern Line.

The Waterloo & City Railway, meanwhile, opened in 1898 and named its two stations after it. The Central London Railway opened two years later, running a line from Shepherd's Bush to Bank. In 1906, Baker Street and Waterloo Railway opened as one of the subsidiaries of the Underground Electric Railways Company of London and became known by its more popular name of "Bakerloo". In the same year, the Underground Electric Railways Company of London formed the Great Northern, Piccadilly, & Brompton Line that ran from Finsbury Park to Hammersmith.

A couple of significant changes took place shortly afterwards.

The first, led by publicity officer Frank Pick, was a clear brand for the company's lines. Pick, borrowing from the London General Omnibus Company, created the roundel symbol for London's Underground Electric Railways company identified with the Underground.

He also introduced common signage and advertising throughout the lines that would become the basis for all other underground railways in the capital. It wouldn't be twenty-five years after Pick's branding system was produced that order would come to the confusion of London's fragmented underground transport network when the London Passenger Transport Board was formed in 1933.

The Board merged the city's transportation networks, including the underground railways, into a single entity called London Transport.

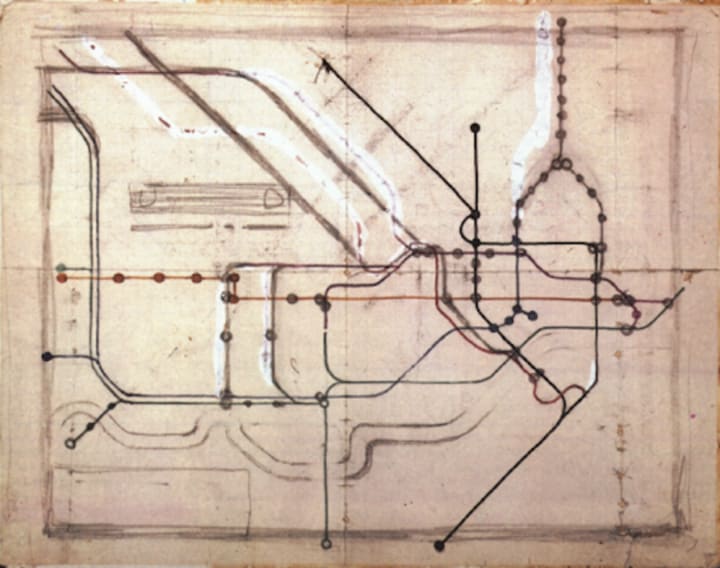

Another significant change for the Underground occurred two years before 1931 when Harry Beck, former Underground Electric Railways Company of London employee, produced his first tube map design that became the standard layout. Before Beck's map, drawings of the underground tended to be geographical and looked like a plate of brightly coloured spaghetti rather than an easily understood interface.

By "straightening the lines, experimenting with diagonals and evening out the distance between stations", Beck created a map that was simple and elegant, better understood by consumers than previous models. Beck attempted to sell it to the Underground Electric Railways Company of London in 1932, but it wasn't interesting. When he tried again in 1933, London's Underground Electric Railways Company bought it for £10 or £600 today.

When the company became part of London Transport, the tube map went with it. It was altered several times, but Beck's original design remained the base for every subsequent version.

Since its opening in 1863,London Underground played a vital role in the lives of Londoners, particularly during the WWII

During the blitz 79 tube station were used as air air-raid shelters accommodating thousands of people every night. To feed the people, the government established six deposit where the food was received and prepared for despatch to the station's canteens. The trains carried the women of the underground catering service who provided refreshments for those Londoners who sheltered for countless nights during the war.

Additionally, the government made use of the tube tunnels to store national treasures and as offices for themselves and the military.

Some Tube stations became small factories where women took jobs churning out munitions and aeroplane parts for the war. We can say, the Underground network became its own little city during the war years.

Between August 1940 and July 1941 nearly 40,000 bombs and millions of incendiaries fell on London.

Thousands of Underground carriages were damaged or destroyed. Worse than that several disasters befell the Tube. Bank and Balham stations were destroyed. But one of the worst civilian disasters during WWII took place at the partially built station of Bethnal Green in east London. Following a false air-raid warning, a woman and child tripped half-way the staircase and, in the ensuing crush, nearly 200 people were killed. The tragedy was so awful that the government kept the details secret for almost two years.

After the war, Clement Atlee's government came into power, and a wave of nationalisation caught London Transports in its wake, incorporating the body into the British Transport Commission in 1948.

The British Transport Commission neglected some of the ageing Underground system's maintenance needs but began work on two new lines: the Victoria Line and the Jubilee Line.

Since the city had stopped growing because of the Green Belt that engulfed it, the two new lines will concentrate more on alleviating current traffic rather than expanding the network to new destinations. The Victoria Line opened in 1968, followed by the Jubilee in 1979, the latter named after the Silver Jubilee of Queen Elizabeth, in 1977. These lines were the first fully automated tube lines.

The iconic phrase "Mind the Gap" could be heard over the PA systems of stations starting in 1969.

The automated message was developed after it became to difficult for station workers to verbally remind the passengers, using a short phrase to save on costs. Sound engineer Peter Lodge, after the original actor demanded royalties for the work, decided to record the phrase himself (as well as "stand clear of the doors").

Other actors later recorded the phrase, including Phil Sayer, Emilia Clarke, and Oswald Laurence, whose voice had been in use since 1969 and was restored to Embankment Station at his widow 's request so that she could continue to hear his voice.

Eventually, the administration of London Transport turned over the Greater London Council, which instituted a system of zones in 1981 to help lower the rates on its buses and underground trains.

The Travel card and the Capital card were launched by London Transport in subsequent years.

In 1984, under the Secretary of Transport, the Underground became part of London Regional Transport, which would be a prelude to the dismantling of the Greater London Council by Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher in 1986 and the transfer of many of its responsibilities to government or borough councils.

The 80s also saw one of the worst accidents in the history of the Underground as a result of a still-lit match, when a fire began on one of the wooden escalators at King's Cross station. The fire caused 31 fatalities, and the resulting investigation led to stricter safety regulations.

Moving thru to the 1990s, many of the trains were given a fresh coat of paint after graffiti removal proved difficult and expensive.

In 1990, the Metropolitan Railway was built out of the Hammersmith & City line, which had been part of since it was built. Extensions proceeded in anticipation of the new millennium and, at the same time, the restoration of a centralised London government meant another shift for the Underground administration.

Prime Minister Tony Blair proposed a new governmental organisation for the boroughs of the city and formed the Greater London Authority, which came into force in 2000. At the same time, it created a new transportation body in Transport for London. TfL helped to develop a public-private partnership in which TfL ran the trains while private companies helped to upgrade the lines.

Despite these challenges, the government retained Underground control until it returned to local authorities in 2003.

The same year, the Oyster card was launched alongside busking in designated areas. As years progress, the Overground was created to ease congestion along with new lines and stations, and the Overground was credited as one of the causes of the regeneration of East London.

The Crossrail was the next great innovation, which was planned to alleviate further congestion of the lines, running between the counties and across the city—renamed Elizabeth Line, in honour of the Queen's long reign. The name will go into use in 2018 along with a purple roundel rather than the usual red. Last year, the London Underground moved to be open twenty-four hours per day on the weekends, mirroring the practices of other major world cities.

The first and one of the most extensive metro subway systems in the world, the London Underground, continues to have a significant role in the city.

It is part of the history of London, as well as its innovations continue to reflect changes within the metropolis. The next time you 're on one of the tube trains, think of everything that the network has been through for over 150 + years and how you're travelling the same path as millions.

About the Creator

Anton Black

I write about politics, society and the city where I live: London in the UK.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.