The Red Summer - Carswell Grove

United States History Untold

The Red Summer - Carswell Grove

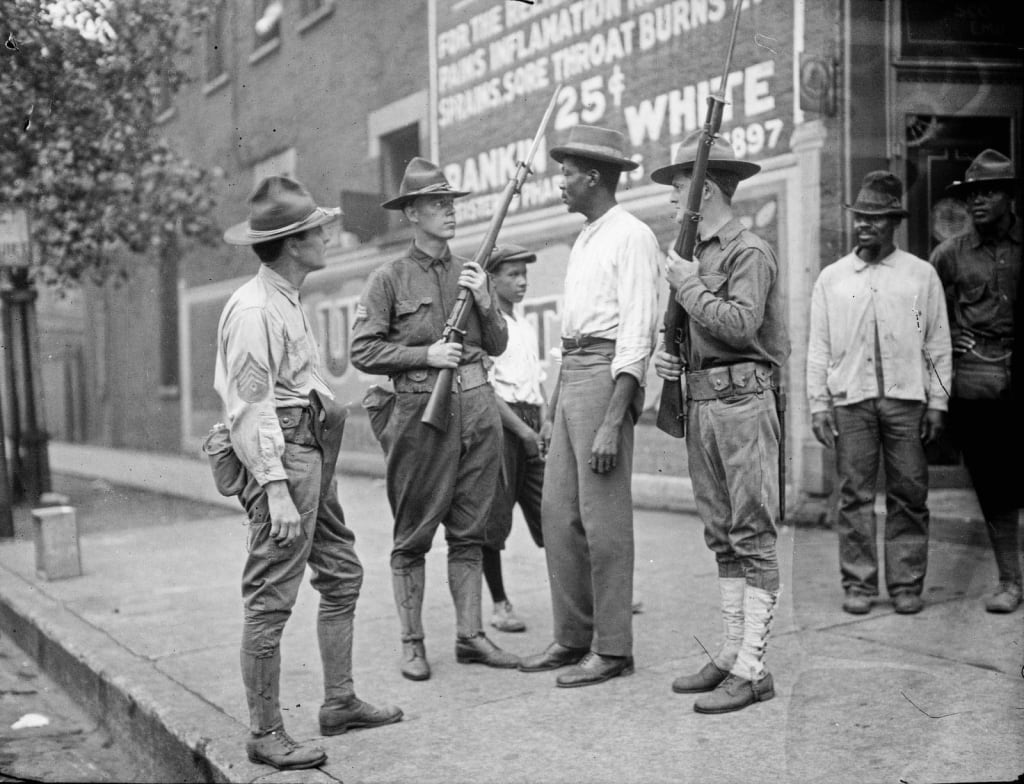

The 13th of April 2019, marked the 100th anniversary of the start of the Red Summer, a period of time when more than 30 cities burst into race riots. White communities attacked Black communities, sometimes with the assistance of police and/or the military. There was no media coverage of this tragic event. There was no acknowledgement this event ever happened. It passed with absolutely no acknowledgement from the media, politicians, or even most of the cities it occurred in, but I will make it a point to remind you of the horror that took place between April and November of 1919.

It would be impossible to detail every lynching, but documentation allows us to look at the Red Summer. In 1919, over 30 race riots/lynchings took place across the United States. One of those riots took place in Georgia at the Carswell Grove Baptist Church.

On April 13, 1919, the Carswell Grove Baptist Church was celebrating its 52nd anniversary. The choir would give a special performance and more than 3,000 people would be present for the gala cookout.

Despite being on the heels of slavery, several Black farmers were doing quite well. Joe Ruffin was one of those people. He owned 113 acres and ran 5 to 7 plows a season, a major accomplishment for a Black farmer. He was relatively prosperous and owned 2 cars. Unlike many Blacks in the area, Mr. Ruffin could also read and write despite having no formal education.

Mr. Ruffin changed into his Sunday best, got in one of his two cars and headed down the road. He joined in the festivities and after some time he remembered he had left the door to his house unlocked and decided to return home. As he sat there an older vehicle pulled alongside him – the occupants – 2 White officers and a distraught Black man in handcuffs.

Joe knew the man, Edmund Scott, his longtime friend. The driver was W. Clifford Brown and the other was Thomas Stephens, both White officers. When Edmund Scott saw Joe Ruffin he frantically shouted to the officers that Ruffin would pay his bond. Mr. Ruffin asked what the problem was and Officer Brown said they had found a concealed gun in Scott’s car. Joe took out a check book and offered to write a check for Edmund’s bond but was told it had to be a cash bond. Being a Sunday, Joe had no way to get a $400 cash bond.

A large crowd gathered around the car, including two of Joe’s sons. Joe reached in and tried to pull Edmund out. Officer Brown became incensed and shouted, “God damn it, get back.” He pulled out his gun and struck Joe in the face. The gun went off, hitting Joe on the left side of his head, knocking him to the ground.

One person said Louis, Joe’s eldest son, rushed the car, wrested the gun from Brown and shot the officer in the head, neck and body, killing him. Two others said that Joe killed Brown with his own gun, firing into the police car. Others said Officer Stephens stepped out of the car with his gun drawn. Another round of gunfire erupted. Edmund Scott, caught in the middle and handcuffed, was shot and killed as he struggled to get out of the way. Officer Stephens was wounded and slumped to the ground.

Officer Brown and Edmund Scott were dead. Officer Stephens lay on the ground, bleeding but conscious. Black men in the crowd attacked him. Some said Joe Ruffin’s two sons led the assault. Someone started Joe’s Ford. He sat in the passenger seat, his head gushing with blood, his ears ringing from the gunshots. He knew immediately he would be lynched when the White mob came for him and there was no doubt it would come – if he lived that long.

Word of the incident spread across the county. Blacks hid in their homes while hundreds of White men grabbed their guns and headed toward Carswell Grove. Joe Ruffin asked to be taken to the only person who could help him – Jim Perkins, the most powerful White man in Jenkins County. Perkins, the chairman of the board of commissioners, had known Joe his whole life. Perkins, who was away from home, rushed home once he learned what had happened.

Perkins got the county jail physician to bandage Joe’s head and then drove to meet the county sheriff, M. G. Johnson, at the scene of the shooting. When the gathering White farmers learned Joe was alive and at Perkins’ house, they became incensed. Perkins and Sheriff Johnson rushed back to protect Joe.

Joe sat bandaged on a cot when Perkins and Sheriff Johnson burst in. “Joe, come on, a mob is coming after you,” they yelled. Joe lie in the back of Perkins’ car as they drove as quickly as they could. Cars filled with angry White men followed them all the way to Waynesboro, the next county. Perkins and Johnson decided to drive on to the nearest big city, Augusta, about 45 minutes away.

While Joe Ruffin lay in his cell, mobs of Whites took vengeance in Jenkins County. White men with guns charged the church at Carswell Grove, firing as they came. Congregants jumped through windows and took off into the woods as mothers tossed children through the windows and then scrambled behind them. The mob torched the building.

White men went to Joe’s farm and grabbed his youngest son, Henry, they also grabbed another Ruffin, John Holiday, Louis Ruffin escaped. The mob took Joe’s car and drove the two men back to the roaring fire at the church. The mob burned the car then hung a chain around one son’s neck and a rope around the other’s. They threw both of Joe’s sons into the flames. It is not clear if they were dead when they were tossed into the fire. At some point the bodies were also shot.

The mob moved south to Millen. Three Black Masonic lodges were torched. At least two more cars owned by Blacks were destroyed. One Black man was shot and wounded; mob members told a reporter that the man was at fault for “acting” suspiciously by running away when they approached. There were reports of other Blacks murdered in remote sections of the county.

The mob went on to abduct and lynch Joe’s friend Willie Williams, who had helped him get up after being shot. Sheriff’s deputies took him into custody. First they put him in the county jail near the courthouse. When they learned a mob was searching for Mr. Williams, they hid him in a nearby stable, but a mob easily found him. They dragged him 3 miles outside of town to a remote swamp. They tortured him and then shot him to death. Supposedly, before he died, Mr. Williams confessed to a plot to kill Brown because of his anti-liquor activities, though he would not tell the mob where Louis Ruffin was hiding. Also the mob claimed another Black man who was arrested, Jim Davis, also “confessed” to the plot and his life was spared. The story made its way, with no evidence, into news accounts of the lynchings, offering Whites justification for what happened. Whites viewed the murders and burnings as all lynchings and such activities were presented – law of retributions.

The White mobs roamed Jenkins County for days. They grabbed a Black man from neighboring Burke County, believing he was Joe Ruffin’s son, Louis. Only when the terrified man was brought back to Millen and properly identified did they turn him loose. Even out of state, Joe had no idea whether a White mob might show up some night to lynch him. Sending mobs far distances to kill people was not without precedent in Georgia. Georgia led the nation in lynchings in 1918 and had the most lynchings of any state since they began keeping records.

The county prosecutor charged Joe Ruffin with the murders of officers Brown and Scott and ordered that he be returned for trial. White mob members were not quoted or named. Blacks were not interviewed. No White person was ever arrested or charged with any crime relating to the riot and lynchings of April 13 or the destruction of the church and other buildings. Perkins, the county commission chairman who had rushed Joe to safety, ruled that no inquest or investigation regarding the White attackers was necessary. No one was ever brought to justice for the crimes against the Black community.

About the Creator

Glenda Davis

The purpose of this blog will be to discuss race relations, learn history and hopefully help us all to be more patient, understanding, emphatic.

I am a 59 year old Black woman, a veteran Sargent of the United States Air Force and a retiree.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.