The New Commonwealth

A short introduction to an Australian Republic

In order to properly develop as a nation-state, the Commonwealth of Australia should become a parliamentary republic.

This would necessitate a transition away from the current system of constitutional monarchy and the removal of the Royal Family of the United Kingdom as the ex officio provider of the Commonwealth’s Head of State.

It is advisable for this transition to be as minimal as possible, to prevent public exasperation, confusion, or distrust, whilst satisfactorily providing a framework for a republican system that provides oversight, accountability, and comfortable cohesion with the current quasi-Westminster political environment. To this end, the model undertakes a revision of other nations’ systems and relocates them into the Australian context.

This modelling, therefore, offers the following recommendations:

1. The retention of the Governor-General, elevated to the position of Head of State, and directly elected to serve five-year terms (renewable once).

2. The retention of the Governor-General as a ceremonial office, with powers that may be executed only on the advice of the Prime Minister (primarily) or, in extraordinary cases, the Executive Council.

3. The transference of all viceregal appointments at state and territory level from monarchical to republican in their styles and symbols, whilst maintaining their system of appointment; as part of

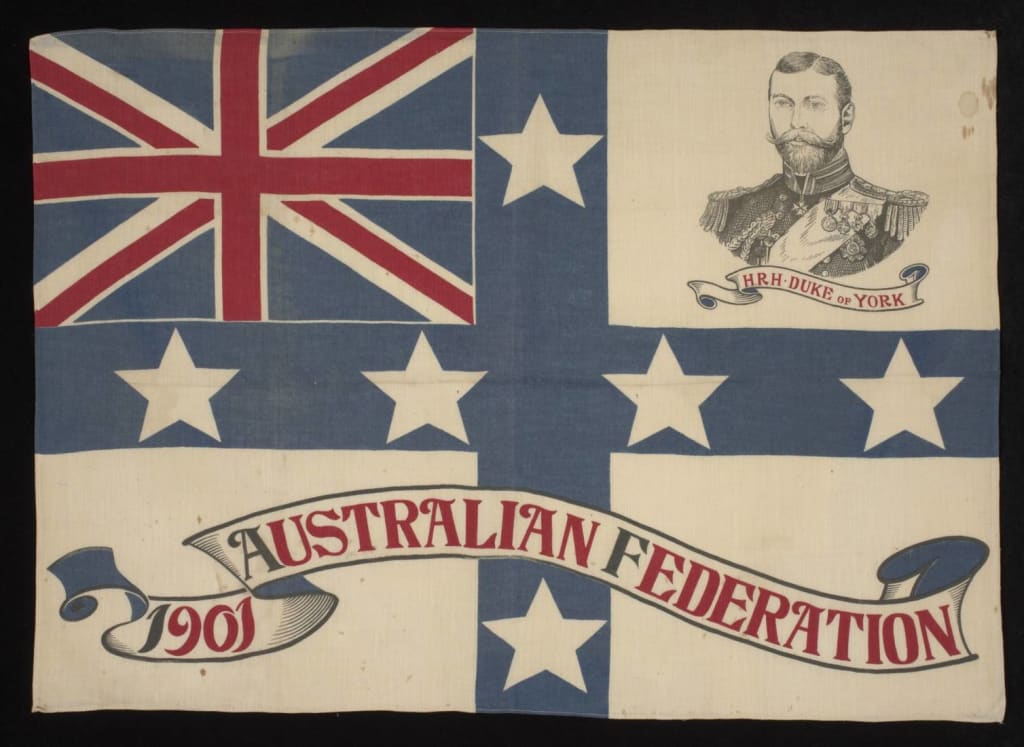

4. The adoption of a five year plan ‘gradual transition schedule’ (GTS) to deal with ancillary aspects of the change in system that may arise, e.g. the national flag, the titles of former viceregal appointments, etc.

The result of these four recommendations would be an independent parliamentary republic, with a ceremonial Head of State (i.e. the Governor-General) — experiencing no conflict of legislative authority between this position and the Head of Government (i.e. the Prime Minister) — whose qualified mandate is received from the citizenry of the Commonwealth.

The System

The Commonwealth of Australia will become a parliamentary republic. This style of government is very different to the presidential (e.g. United States) or semi-presidential/dual executive (e.g. France) system. The everyday governance of the nation will not change dramatically, nor will our international obligations. Australia will not leave the Commonwealth of Nations, often known simply as the Commonwealth, by becoming a republic.

In a republican Commonwealth, the emphasis for legislative matters will remain in the Parliament; federal laws will be debated, passed, rejected, or repealed through the Federal Parliament. The Head of Government will be the Prime Minister, who presides over the Cabinet and Outer Ministry, all of whom are drawn from the Parliament. By keeping this, the Commonwealth retains the key principle of ‘responsible government’ that is so often found in Westminster systems. No change to the existence or powers of states and territories is made through becoming a parliamentary republic, but the viceregal element of Governors and Administrators will be removed and replaced.

The Head of State will be the Governor-General. In the current system, which is a constitutional monarchy, the Head of State is Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II, acting in her capacity as Queen of Australia. She is represented in Australia by the Governor-General, who, since 1965, has been drawn exclusively from the local pool of talent.

The adoption of a parliamentary republic model will see the following changes take effect:

1. The abolition of the title of ‘King/Queen of Australia’. The monarch of the United Kingdom has no further formal role in Australian public life.

2. The removal of the viceregal element of the Governor-General position. The Governor-General has no further political, systemic, or representational connection to the monarch of the United Kingdom.

3. The elevation of the Governor-General to the position of Head of State. The Governor-General, no longer a viceregal representative, fills the absence left by the abolition of the monarch. All necessary ceremonial duties are performed by the Governor-General.

4. The adaptation of existing styles, symbols, and associated ephemera. The remaining expressions of the constitutional monarchy, found in symbols and the like, will be gradually removed. It is important that care is taken to acknowledge the cultural importance of much of this ephemera, whilst it is equally imperative to transition away from their official public display. Republican — that is to say, Australian — symbols will replace them. This will take place as part of a ‘gradual transition scheme’, as developed by Parliament or overseeing statutory body.

The Head of State

The Governor-General will serve as the Commonwealth of Australia’s Head of State. It is important to note that the Governor-General will not have executive powers. This, put simply, means that the Governor-General will have no control over political policies, laws, and/or regulations. The role of the Governor-General will be very similar to its current form: ceremonial and structural. The core differences are the method by which the Governor-General is selected and the authority to whom the Governor-General is officially responsible.

The following provisions and disqualifications apply to the position of Governor-General of the Commonwealth of Australia:

Eligibility and Specific Disqualifications

It is key to ensure that the new system is not seen as a “politicians’ republic”. One of the major detractions from the republican movement is the idea that currently serving or future politicians would create new sinecures or means of consolidating their power. In order to temper these concerns, it is necessary to introduce time periods during which a person is disqualified from the office of head of state. The objective, simply, is to prevent a merry-go-round of politicians dominating the highest office in the country. The length of the disqualification is not particularly long, as it does not seek to unnecessarily and indefinitely preclude popular, competent political candidates from standing.

1. Any person who meets the eligibility requirements of the Federal Parliament — as stipulated in the Constitution and the Electoral Act — likewise qualifies as a candidate for Governor-General, except for the following specific disqualifications:

(a) No currently serving parliamentarian or elected representative, at state or federal level, is eligible to serve as Governor-General.

(b) Any person who has served as a parliamentarian in the Federal Parliament is precluded from serving as Governor-General for a period of three years following the cessation of their tenure.

(c) Any person who has served as Prime Minister, or as a minister, assistant minister, or parliamentary secretary for any portfolio in the Federal Government, is precluded from serving as Governor-General for an additional two years from the expiration of their base disqualification.

(d) Any person who has served as a parliamentarian or elected representative in state parliament or territory legislature is precluded from serving as Governor-General for a period of three years following the cessation of their tenure.

(e) Any person who has served as Premier or Chief Minister, or as a minister, assistant minister, or parliamentary secretary for any portfolio in a state or territory government is precluded from serving as Governor-General for an additional two years from the expiration of their base disqualification.

(f) Any person who has previously served two terms as Governor-General, complete or otherwise, is ineligible to serve as Governor-General.

Nomination

The head of state position is a national issue, contained within a federal system. Lists of candidates cannot be allowed to be solely dominated by one state, or by two states in collusion with one another. Similarly, sceptics of direct election have expressed concern in the quality of candidates who might offer their services; those of questionable moral character or of unserious candidacy must not be totally excluded — the principles of democracy still apply to them — but it is not too much of a hassle to require them to seek nominations through a filtration method. This is used elsewhere to great effect. One of its great strengths is that it combines the controlled but democratic style of minimalist republicanism (i.e. parliament chooses the head of state) with the greater legitimacy of the direct election that follows it.

The preferred nomination method for this programme draws upon what is known as the Jones-Pickering model.

1. A prospective candidate must seek nomination to stand for the office of Governor-General.

2. Each state and territory legislature has the power to nominate one eligible candidate. Upon acceptance of the nomination, the candidate is added to the ballot.

3. A nominated individual may decline the nomination by expressing their wish, in writing, to the Chief Justice of the High Court, and to the presiding officers of the legislature from which nomination was secured. This must be done prior to the closing of nominations.

Term Length, Election , and Campaigning

Currently, Governors-General serve at His or Her Majesty’s pleasure. By convention, this is capped at five years per term, which may be renewed. For a republican head of state, the balance needs to be found between achingly long tenures and those so short that they give the public ‘election fatigue’. Somewhere between five and ten years appears to be the happiest medium. For the purpose of this model, I have selected five year terms. This should mean that at least one — perhaps even two — entire parliament(s) shall have expired between head of state elections. This is important for two reasons: (a) it shall allow a fresher, more representative batch of parliamentarians to take place in the nomination process, and (b) it does not significantly add to the burden of multiple elections that already exists in a federal system with three levels of compulsory voting.

This leads to another question: should voting for the head of state be compulsory? As it is a symbolic position with no legislative authority, should Australians be allowed to abstain from voting altogether? The Jones-Pickering model, cited above, answers in the affirmative. Direct election republicanism, however, is predicated upon a core idea of civil participation; our institutions have legitimacy because they are accepted, utilised, and participated in. To this end, this model prefers that compulsory voting is retained. The compulsory vote culture, with its attendant ‘democracy sausage’, could be usefully applied to the head of state office, lending it legitimacy, and making sure no damage is done to participation rates in general (i.e. parliamentary) elections.

On the issue of campaigning, this model holds that it should be regulated and discouraged but not actively prohibited. As compulsory voting is in place, there is no need for public engagement "get out the vote" campaigning. The punishment for crass electioneering should be delivered by a discerning electorate, rather than the government or an electoral commission. As in the Jones-Pickering model, a small educational stipend will be given to candidates to assist in expressing their positions. Likewise, candidate statements will be provided on the Australian Electoral Commission website and other non-partisan places (e.g. public libraries, etc.). No further public assistance, either financial or material, will be given to candidates. Regulations of broadcast advertising, for example, will be left to the Federal Parliament.

1. The Governor-General is directly elected by the eligible parliamentary electors among the citizenry, as determined by constitutional and legislative provisions, to a term of five years from the date of inauguration.

2. The inauguration of the Governor-General shall take place no more than two months following the official reporting of the election results.

3. The term of five years is renewable once.

4. Elections are held using the same methodology as the voting for the Federal House of Representatives (i.e. a single transferrable vote). If a nomination is uncontested, the sole candidate is declared elected.

5. Voting for the head of state is compulsory for those eligible and enrolled to vote in other elections (i.e. local, state, and federal elections).

6. Campaigning is regulated and discouraged but not prohibited. Educational stipends are provided by the Federal Government on a non-partisan basis.

Powers

As stated previously, the head of state in this model is purely ceremonial. In essence, their powers are directly comparable to those expressed by the Governor-General in our current system. The difference is mainly one of principle: the outdated monarchical connection to a system halfway around the world is replaced by something quintessentially Australian, by our own design. There is no concern under this model that the Governor-General may be mistaken for the Prime Minister in terms of actual power. The Governor-General, unquestionably, acts on the advice of the Prime Minister. A very minor change in the current powers is proposed by this model. A Governor-General, in giving Royal Assent to a piece of legislation, may recommend changes under the current system. In this proposal, a Governor-General, giving (decidedly non-Royal) Assent, may refer passed legislation to the High Court of Australia, in order to determine its constitutionality. This is borrowed from other systems and provides a level of oversight which is not too onerous and does not deviate harshly from the ceremonial nature of the office.

1. The Governor-General holds a ceremonial position. The Governor-General does not have legislative authority but does sign proposed legislation into law by giving Assent.

2. The Governor-General must act on the advice of the Prime Minister, as head of the Commonwealth’s federal government. The Governor-General may receive advice from the Executive Council, as already takes place.

3. The Governor-General is the ceremonial head of the Australian Defence Force (ADF). The rank held is Commander-in-Chief. All operational and logistical control of the ADF is delegated to the relevant members of the Executive. The Governor-General issues commissions to officers, on the advice of the relevant ministers.

4. The Governor-General has the power, on the advice of the Prime Minister, to convene, suspend, or dissolve the Federal Parliament. This includes double dissolution, if the constitutional provisions have been met.

5. The Governor-General has the power, on the advice of the Prime Minister, to appoint or dismiss ministers or assistant ministers of the federal government, including the Prime Minister.

6. The Governor-General has the power, on the advice of the Prime Minister, to appoint people to fill officers as required by constitutional or statutory provision.

7. The Governor-General provides Assent to legislation that has passed both Houses of Parliament, signing it into law. The Governor-General may also take advice and refer the proposed legislation to the High Court of Australia, to test its constitutionality.

Conclusion

What is proposed above is simply a system that may be adopted in a republican Commonwealth. It is certainly possible to make adjustments and to highlight potential flaws in reasoning. It may be that there is no perfect model for the Australian state, either monarchical or republican. This model, however, has sought to address some of the more rational concerns expressed by those who are either opposed to republicanism or, more specifically, to direct election of the head of state.

In terms of power, the Governor-General has very little. They retain much of what they had under the monarch but they are only answerable to the Australian people.

In terms of selection, provisions have been put in place — in addition to the attitude of the Australian people — to make sure the office of head of state is not a partisan sinecure for departing politicians, desperate for relevancy or legacy.

In terms of election, Australians have a genuine say in who is the first citizen of our nation.

In terms of stability, terms of five years and the lack of any legislative authority or control protect us from the unpredictable circuses of presidential or semi-presidential systems.

In terms of heritage, the model allows us to retain our functioning quasi-Westminster system whilst also providing room for us to develop and recognise both our oldest and newest cultural groups. When this model is adopted, the system which precludes the oldest living culture on the planet from providing our continent's First Citizen withers away.

We are a modern, independent nation and our system should reflect this.

(Special thanks to Dr Benjamin T. Jones and Prof Paul Pickering for their work on the Jones-Pickering model, a fine system of selection and a testament to the ideas present in modern Australian republicanism.)

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.