The Emperor of America

Joe Biden and Donald Trump could learn much about leadership from Norton I, the first and only Emperor of the United States

"San Francisco is a mad city, said Rudyard Kipling, "inhabited for the most part by perfectly insane people."

It's true the city was used to having her fair share of oddballs.

All across town, lithesome Lillie Hitchcock Coit, ‘the darling of the firefighters’, would follow Knickerbocker Engine Co. №5, cheering them on and rousing the crowd as they fought back infernos. In the Mission District, the enigmatic King of Pain sold invisibility ointment outside the Pacific Clinical Infirmary, not far from the bars frequented by the reincarnation of George Washington, replete in a Continental uniform of tanned buckskin. Nightly, the General would retire to pour over maps and plans at his ‘General Headquarters’, the Cobweb Palace saloon down by the wharves. The Palace’s owner, Old Abe Warner, was a local character in his own right. He would barter drinks for the artworks, antique weapons, totem poles, and a collection of exotic pets — live bears and kangaroos among them — that cluttered the place. The name came from Warner’s refusal to either kill spiders or remove their web strands, which, over the course of thirty years, covered everything.

Then, as now, the Misty City had a reputation for accepting, even welcoming, the most eccentric of citizens.

Even by these standards, the clerk on duty at The San Francisco Bulletin on September 18, 1859, hardly knew what to make of the man with the look of a hobo and the air of an aristocrat to ask that the paper publish a proclamation on his behalf. Still, the confused clerk dutifully handed the note to his editor.

On seeing it, the Bulletin’s editor, George Kenyon Fitch, instinctively understood two things. First, that the man’s claims and his ‘proclamation’ were patently absurd, and secondly, that the city he loved was in mourning.

An Emperor Among Us

David C. Broderick was a California State Senator, respected abolitionist, and beloved native son of San Francisco. Now he was dead and every flag at half-mast. Just two days earlier, a political feud between Broderick and pro-slavery Chief Justice David S. Terry had boiled over into a sunrise pistol duel by a lake outside of Sacramento. Broderick discharged his pistol into the ground. Terry fired his through Broderick’s right lung.

Sensing that a little levity might be just what San Francisco needed to begin to recover, the September 18 edition headline asked ‘Have We An Emperor Among Us?’, under which Fitch wrote:

This forenoon a well-dressed and serious-looking man entered our office and quietly left the following document, which he respectfully requested we would examine and insert in the Bulletin. Promising him to look at it, he politely retired without saying anything further. Here is the paper:

At the peremptory request of a large majority of the citizens of these United States, I, Joshua Norton, formerly of Algoa Bay, Cape of Good Hope, and now for the past nine years and ten months of San Francisco, California, declare and proclaim myself Emperor of these U. S., and in virtue of the authority thereby in me vested, do hereby order and direct the representatives of the different States of the Union to assemble in the Musical Hall of this city on the 1st day of February next, then and there to make such alterations in the existing laws of the Union as may ameliorate the evils under which the country is laboring, and thereby cause confidence to exist, both at home and abroad, in our stability and integrity.

Thus, aided by the fourth estate and who welcomed with open arms by a willing populace of San Francisco, began the reign of Norton I who would, for the next twenty years, be the Emperor of the United States.

San Franciscans immediately took to their new ruler. Although he was occasionally ridiculed, the people by and large humoured his delusion.

His daily rounds of the city were always met with salutes and bows from passers-by.

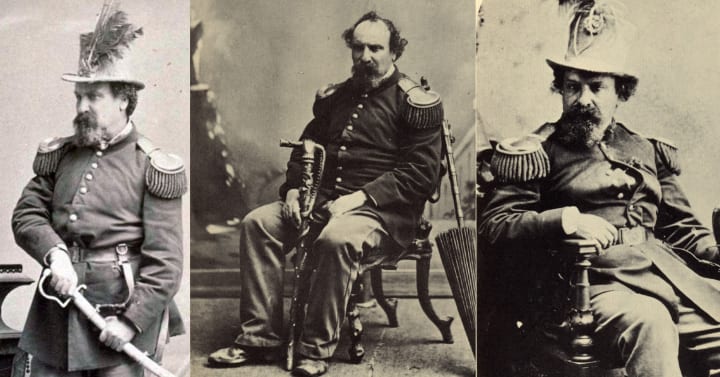

His state dress was a blue military uniform with tarnished gold plated epaulets, a gift from the officers of The Presidio army post. Topped by a beaver hat with a peacock feather, Emperor Norton would make regular inspections of police stations, fire houses and construction sites in San Francisco, the capital and jewel in the crown of his empire.

He hadn’t always been Emperor, of course.

In 1849, Joshua A. Norton, English-born and South African-bred, left his home in Algoa Bay to seek his fortune, as many did during the days of the California Gold Rush, in America. And a fortune he found.

Arriving in California with a $40,000 inheritance, Norton turned his boundless energy and a shrewd business sense toward a variety of ventures, most successfully real estate and importing. Four years later, he was worth around $250,000, making him a multi-millionaire by today’s standards, though his financial downfall was even more rapid than his rise.

Anticipating a huge demand among San Francisco’s large Chinese migrant population, Norton gathered a consortium and gambled his entire fortune on a complicated plan to corner the local rice market. Competitors got wind of his plan and attempted to do emulate it. The imported rice surplus and litigation that followed wiped him out.

By 1957, Norton lost not only his fortune but his sanity as well. The once respected business spent two years as a recluse living in a tiny room of a boarding house until his sudden reappearance and reinvention.

Although a rather scruffy monarch, the emperor carried himself with a nobility befitting his grand position. However, he was not an inaccessible ruler, always making himself available to his loyal subjects. And also, it seems, to his fellow heads of state. He would often send correspondence to Abraham Lincoln and Queen Victoria.

He frequently bequeathed titles of nobility on his subjects. Such nobility could be for the duration of their mortal lifetime or for a day, giving rise to the expression ‘queen for a day’. These were granted to anyone from the city’s Board of Supervisors - who each received a patent of nobility in perpetuity for replacing his uniform, listed in the annual budget as a ‘necessary expense’ - to a stranger on the street who seemed to be having a bad day.

He patronised the city police department, his ‘imperial constabulary’, inspecting their ranks twice a year and reviewing new cadets at the academy, after which he would give a grandiose speech to the assembled crowd.

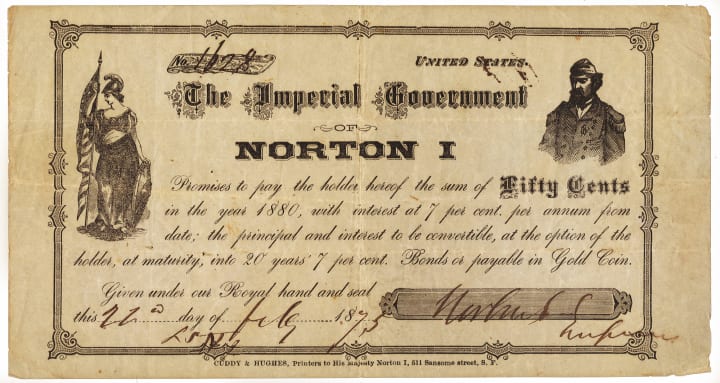

He even issued his own currency, fifty cent bonds produced free of charge by a local printery, which he would exchange for legal currency to support his modest needs. Many local businesses soon began accepting this script as legitimate currency. When short of funds, Norton would collect from his subjects their royal taxes, always a small amount to cover only his immediate needs, for which he would instantly provide a handwritten receipt.

In his novel The Wrecker, Robert Louis Stevenson marvelled at the Emperor’s sway over the city.

“Of all our visitors, I believe I preferred Emperor Norton; the very mention of whose name reminds me I am doing scanty justice to the folks of San Francisco,” Stevenson wrote.

In what other city would a harmless madman who supposed himself emperor of the two Americas have been so fostered and encouraged? Where else would even the people of the streets have respected the poor soul’s illusion? Where else would bankers and merchants have received his visits, cashed his cheques, and submitted to his small assessments? Where else would he have been suffered to attend and address the exhibition days of schools and colleges? Where else, in God’s green earth, have taken his pick of restaurants, ransacked the bill of fare, and departed scatheless?

Norton would, according to legend, have the freedom to eat in any restaurant he chose without charge, rewarding his guest by allowing them to display a sign signifying ‘By Appointment to his Emperor, Norton I’. While doubtless an exaggerated claim, there was a certain truth to it, given that imperial endorsement would invariably increase an establishment’s tourist trade.

Mark Twain initially suspected the Emperor act to be yet another fraud to bilk tourists before becoming one of Norton’s most outspoken supporters. He had come to understand the Emperor’s beliefs were as genuine as his madness.

Twain knew the Emperor well as both subject and neighbour. Twain lived above the offices of his employer, The Daily Morning Call newspaper, which happened to be next door to the boarding house where Norton continued to reside, his fortunes never rising as much as the newspapers or the restaurants and tailors who profited from his custom. The two would often meet and talk as the Emperor began daily inspections of his capitol.

Stately delusions aside, Twain found Norton to be remarkably lucid and intelligent in all other matters. He possessed an instinctive understanding of his adopted country and her people as well as remarkable foresight.

Twain also saw more than the comical side of the Emperor. For all the pomp and circumstance and deference which he insisted upon, Norton was heavily invested in local national and world affairs, and the responsibilities that came with his position weighed on him heavily. Of greatest concern to him was a despair at the corruption, indifference and incompetence of elected bodies.

While his first proclamation, the declaration of his ascension as Emperor, is the most know and quoted, it is his second decree that tells us more about this side of him.

By 1859, voting rights in the United States, if not perfect, were as advanced as they had ever been. By now, in every state, all white men were able to vote regardless of property-owing status, a tactic that had excluded many citizens right to vote. Yet states still found workarounds to voting acts, notably by adding taxpaying-status clauses.

Incensed by this inequality, Norton’s second proclamation declared that:

It is represented to us that the universal suffrage, as now existing throughout the Union, is abused; that fraud and corruption prevent a fair and proper expression of the public voice; that open violation of the laws are constantly occurring, caused by mobs, parties, factions and undue influence of political sects; that the citizen has not that protection of person and property which he is entitled to by paying his pro rata of the expense of Government - in consequence of which, we do hereby abolish Congress.

George Fitch, a progressive himself, and by now warming to the idea that support for the Emperor was good for the newspaper business, prefaced this declaration by saying that “His Imperial Majesty, Notion I, has issued the following edict, which he desires the Bulletin to spread before the world. Let her rip!”

Next, Norton issued an edict abolishing the Supreme Court in disgust at the legal fraternity’s protection of one of their own by acquitting Chief Justice David S. Terry for partaking in the illegal duel that ended the life of Senator Broderick.

His Majesty was quickly becoming deeply involved in affairs of state from the local to the international. He devoured the daily newspapers and regularly attended sessions of state and local officials. Having caused a ruckus when a ticket collector had the temerity to refuse to accept the Emperor’s imperial currency, Leland Stanford, the railroad’s owner, issued Norton a lifetime pass on all Central Pacific trains, allowing him to attend the California legislature in Sacramento, though he was often unimpressed by what he saw there.

In 1860, fearing the inevitability of a war between the states, Norton volunteered his services to Abraham Lincoln to act as a mediator between North and South. President Lincoln — or, most likely, a wag at one of the newspapers — politely declined the offer by telegram.

Depressed and frustrated at his inability to halt the coming war, Norton consoled himself in the knowledge that California would not be drawn too deeply into the conflict and turned his attention to world affairs.

Seeing sabre-rattling and unrest abroad, he invited other world leaders to join him in forming a ‘League of Nations’ in order to resolve disputes peacefully and to attend matters of international concern.

Closer to home, Norton was alarmed at the 1861 invasion of Mexico by French forces, supported by Britain and Spain. Seeking to dissuade the installation of Maximilian I, an Austrian aristocrat, as monarch of the Second Mexican Empire, Norton added Protector of Mexico to his title and threatened to amass 10,000 American troops at the border to defend its Southern neighbour.

When the troops failed to turn up as ordered, and when leaders of the Hebrew, Catholic and Protestant faiths ignored his calls of support in bringing peace to Mexico, he abandoned his role, conceding that it was “impossible to protect such an unsettled nation”.

Mad Monarch, Mad City

Despite such a keep involvement in world affairs, Norton never neglected to tend to San Francisco, the jewel in the crown of his empire, and issued a number of decrees specifically for the betterment of his beloved adopted home.

“Whoever after due and proper warning shall be heard to utter the abominable word ‘Frisco’, which has no linguistic or other warrant, shall be deemed guilty of a High Misdemeanor,” he decreed. For this crime, Norton imposed a steep $25 fine (though, benevolent to a fault, Norton invariably let the offender off with the ‘due and proper warning’ along with a stern lecture).

The proposal dearest to his heart was to build a bridge spanning the San Francisco Bay to Oakland. This was in 1869, more than sixty years before the construction of the Bay Bridge. His design proposals bore more than a passing resemblance to the current structure. He even correctly estimated that only a suspension bridge would be able to support the immense weight of such a structure. This was at a time when the only suspension bridges were rope bridges in Africa.

Wherever he went Emperor Norton was attended by his royal court.

Ah How was a Chinese gentleman named who was appointed by Norton to act as his advisor, his Grand Chamberlain, and therefore the most prominent and respected member of that maligned community.

The two would spend hours together walking the streets of the capitol or sitting on park benches.

It must have seemed unusual in that time for a Chinese man to have such access to an Emperor, but Norton despised the animosity that was directed towards a community that had contributed so much to the city from the Gold Rush and beyond.

It was likely Ah How who alerted Norton to an anti-Chinese protest that was heating up on night in 1867. Arriving just before tensions between two large groups reached boiling point, Norton stood between the groups and recited The Lord’s Prayer over and over until both groups dispersed without violence.

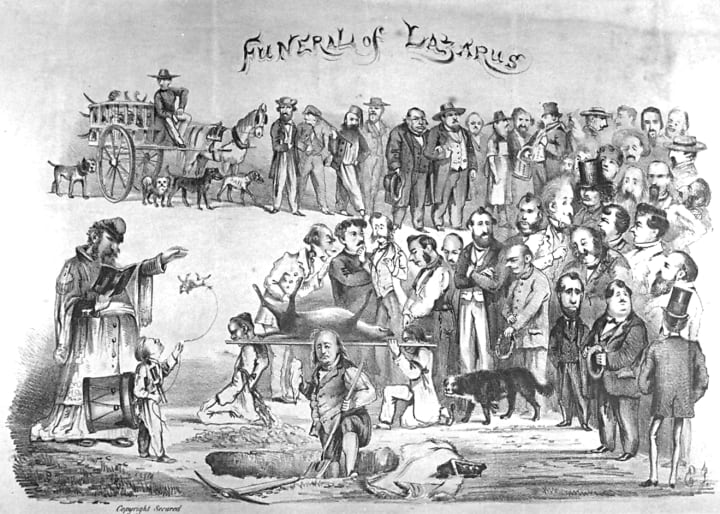

As respected as Ah How was, his fame paled in comparison to Bummer and Lazarus.

At the San Francisco opera house, there were three seats permanently reserved. One was for the Emperor, the others, at either side, were for Bummer and Lazarus, the most famous mongrel dogs in the city. Though usually referred to as the Emperor's pets, they were owned by no-one but themselves. Bummer and Lazarus lived not with Norton, but beneath the Bulletin building. They would rush to greet him when he appeared each morning and accompany him faithfully on his rounds, attaining considerable repute of their own. They were the only dogs exempt from the city regulation against strays roaming the streets. When a city dog catcher mistakenly arrested one of them, only the intervention of the Emperor himself stopped an angry mob from assaulting the man.

Lazarus' service to his Emperor ended one October night in 1863. He was reportedly killed by a speeding fire engine as he crossed a road. Other reports suggested he was poisoned by the parents of a boy he had bitten, leading to San Franciscans posting a $50 reward for the capture of the poisoner.

When Bummer passed away a few years later, a lonely and heartbroken monarch.

On 11 November 1865, The Californian newspaper published an obituary by Mark Twain, who turned it into a treatise on homelessness, ageing, and the fleeting nature of celebrity:

The old vagrant 'Bummer' is really dead at last; and although he was always more respected than his obsequious vassal, the dog 'Lazarus,' his exit has not made half as much stir in the newspaper world as signalised the departure of the latter. I think it is because he died a natural death: died with friends around him to smooth his pillow and wipe the death-damps from his brow, and receive his last words of love and resignation; because he died full of years, and honor, and disease, and fleas.

He was permitted to die a natural death, as I have said, but poor Lazarus 'died with his boots on' - which is to say, he lost his life by violence; he gave up the ghost mysteriously, at dead of night, with none to cheer his last moments or soothe his dying pains. So the murdered dog was canonized in the newspapers, his shortcomings excused and his virtues heralded to the world; but his superior, parting with his life in the fullness of time, and in the due course of nature, sinks as quietly as might the mangiest cur among us. Well, let him go.

In earlier days he was courted and caressed; but latterly he has lost his comeliness - his dignity had given place to a want of self-respect, which allowed him to practice mean deceptions to regain for a moment that sympathy and notice which had become necessary to his very existence, and it was evident to all that the dog had had his day; his great popularity was gone forever. In fact, Bummer should have died sooner: there was a time when his death would have left a lasting legacy of fame to his name. Now, however, he will be forgotten in a few days. Bummer's skin is to be stuffed and placed with that of Lazarus.

With both loyal companions now gone, many noted a change in the Emperor. He continued with his duties but, after Bummer's death, it was with a noticeably heavy heart.

Still, he remained unfailing welcoming to the visitors to his fair city, and continued to issue proclamations and attend events of import. He still inspected walked the streets of San Francisco every day, making sure the Empire continued to flourish for as long as he reigned.

Le Roi Est Mort

By 1880, Mark Twain had long departed San Francisco. No longer a simple newpaperman, he was now a celebrated author. With The Innocents Abroad, The Gilded Age, and The Adventures of Tom Sawyer under his belt, he was working on a new novel, The Prince and the Pauper. But he still kept up with news from back home. He was living in Connecticut when he read the news in the San Francisco Chronicle.

Le Roi Est Mort, read the headline.

The Emperor is dead.

During a regular evening inspection of his beloved city, the Emperor suffered a stroke corner of California and Dupont. When the coroners emptied his pockets, all that was to be found were a few coins and two telegrams, purportedly from Czar Alexander II and the President of France. Emperor Norton ended his reign just as he had begun, penniless and alone.

Every paper in California reported the story but none more tenderly than Twain’s old employer, The Daily Morning Call:

“On the reeking pavement, in the darkness of a moonless night, under the dripping rain, and surrounded by a hastily-gathered crowd of wondering strangers, Norton First, by the grace of God, Emperor of the United States and Protector of Mexico, departed this life. Other sovereigns have died with no more of kindly care; other sovereigns have died as they have lived, in all the pomp of earthly majesty; but death having touched them, Norton First rises up the exact peer of the haughtiest King or Kaiser that ever wore a crown. Perhaps he will rise more than the peer of most of them. He had a better claim to kindly consideration than that his lot “forbade to wade through slaughter to a throne, and shut the gates of mercy on mankind.” Through his harmless proclamations can always be traced an innate gentleness of heart, a desire to effect uses and a courtesy, the possession of which would materially improve powerful living princes, whose names will naturally suggest themselves.”

The loss of their beloved ruler was a severe blow to San Francisco. Businesses closed and flags around the city flew at half-mast out of respect, just as they had for another great statesman on the day the Emperor appeared.

The Pacific Club spared him the indignity of a pauper’s funeral by gathering contributions to provide a fitting farewell for their lost leader. A subscription list signed by each contributor still holds pride of place in the clubroom. Contributions were generous, ensuring the most lavish farewell the city had ever seen. There were so many floral tributes and wreaths that the coffin lid was completely covered.

20,000 people turned out to pay their last respects, taking part in a funeral procession that stretched for more two miles.

The Emperor Lives

In her 2018 book, Fascism: A Warning, Madeleine Albright notes that Donald Trump “shown an astonishing disregard for facts, libelled his predecessor, threatened to lock up political rivals, bullied members of his own administration, referred to mainstream journalists as enemies of the American people, spread falsehoods about the integrity of the US electoral process, touted mindlessly nationalistic economic and trade policies and nurtured a paranoid bigotry toward the followers of one of the world’s foremost religious.”

How different to an Emperor who would attend Jewish synagogues every Saturday and a different Christian church on Sunday because “I think it my duty to encourage religion and morality by showing myself at church and to avoid jealousy I attend them all in turn.”

The one who tried to come to the aid of Mexico, rather than to build a wall around it.

Who decried voter disenfranchisement by the political class, rather than see it used as a tool.

And who showed wisdom and forgiveness to those you wronged him, even to point of indignity.

He may have been the ‘Mad Monarch of America,’ yet, during his twenty-year reign, there was only a single time that Emperor Norton’s legitimacy would be called into question by the establishment. And even then, he handled it with a poise and dignity not often seen in our leaders anymore.

In 1867, the seventy-two ‘regular’ members of the San Francisco Police Department, for budgetary reasons, were supplemented by sixty-six uniformed officers, or ‘locals’ who were paid not by the city, but by property owners. Locals wore the same uniform as Regulars and had all the same powers, but patrolled only the beats around their benefactors.

One young local, Armand Barbier, was requested by the owner of the The Palace Hotel to remove the scruffy man who had wandered in demanding an empty chair and a newspaper. When the Emperor refused to leave until he had extracted an apology for his shoddy treatment, the young rookie arrested him for vagrancy and took him back to the station, much to the dismay of new Police Chief Pat Crowley.

When told by the desk sergeant that the vagrancy charge did not apply to a man who had a fixed abode, Barbier found the only possible way to make matters worse. He changed the charge to lunacy.

Such was the seriousness of the situation, by the time Crowley had been informed, The Bulletin already had the story, which George Fitch promptly editorialised in the evening edition:

In what can only be described as the most dastardly of errors, Joshua A. Norton was arrested today in the Palace hotel. He is being held on the ludicrous charge of “Lunacy.” Known and loved by all true San Franciscans as Emperor Norton, the kindly Monarch of Montgomery street is less a lunatic than those who engineered these trumped-up charges, as they will learn when His Majesty’s loyal subjects are fully apprised of this outrage.

Fitch called on all “right-thinking citizens to be in attendance tomorrow at the public hearing to be held before the Commissioner of Lunacy, Wingate Jones.”

Crowley knew he would have a riot on his hands if the case made it to the Commissioner, so he did the only thing he could, to intervene personally. Swiftly, he moved to release the Emperor, handing over a receipt to collect his possessions, a room key and $4.75 in legal tender, which faithful Ah How was on hand to sign as a witness.

This left Crowley with just one last task. As the new Chief of Police, Crowley had been sent in to reform a force that had a reputation for being authoritarian and heavy-handed. He needed to send a message that the new look force could be trusted. There was nobody who could be a greater ally than the man who, especially among the migrants, the poor, and the disenfranchised, was held in higher regard than any policeman or politician in the city.

Upon releasing Norton, Crowley told the Daily Alta newspaper that “Norton was in his day a respectable merchant, and since he has worn the Imperial purple has shed no blood, robbed nobody, and despoiled the country of no-one, which is more than can be said for his fellows in that line.”

The Emperor publicly forgave Crowley’s force for their error in judgement, appeasing the growing numbers of protesters. Armand Barbier, on account of his youth, received a royal pardon.

Thereafter, every regular policeman in the city saluted whenever their Emperor walked by.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.