Strong And Stable, But At What Cost?

Strength & stability should be means to an end, not an end in themselves.

“Strong and stable” has been repeated over and over during the last two months, since UK Prime Minister Theresa May called a General Election on 18th April. But what does that mean? We have been asking the same question of “Brexit means Brexit” and we still don’t have an answer. But we can shed some light on the former by analysing her behaviour since the Brexit vote.

It has been almost a year since the British electorate voted by a tiny margin to leave the EU. At that time, it wasn’t entirely clear what that would actually look like, but it didn’t matter: it was so unthinkable that the conditions for success were not even set. A threshold of two-thirds of the vote, a supermajority, is required in many voting systems both at the institutional level and in national and international government. It would be reasonably expected that a vote on something so crucial would have the terms clearly set out beforehand and that a simple majority would not be enough. There would also be conditions related to minimum turnout, and whether or not the referendum is legally binding. The UK’s referendum on EU membership is not legally binding, and yet it is being treated as if it is.

Anti-EU sentiment has been bubbling away amongst the political commentariat ever since the UK joined the single market in 1973. But the catalyst for the UK’s current predicament can be traced back to mid-2013 when former Prime Minister David Cameron promised to hold an in/out referendum on EU membership if the Conservatives won the 2015 general election. This promise was made under pressure: David Cameron was leading a coalition government with the unlikely bedfellows of the Liberal Democrats. He lacked absolute authority and needed to strengthen his party’s rule. The coalition acted to temper the true aims of Cameron’s party, and the Conservatives were further weakened by the rise of UKIP. This matter needed to be put to bed, once and for all. The decisive Conservative victory in the 2015 election met one-half of Cameron’s bargain. Now he had to deliver on the other.

It was widely believed to be a gamble worth taking; while the Conservatives were hoping to win over the Eurosceptics who had left them for UKIP, it was not thought that they were powerful enough to drive a successful “Leave” vote. People from across the political spectrum agreed that it would be a foolish move to burn economic, social, and political bridges, especially at a time of financial worry. Theresa May herself was a staunch Remain campaigner, but she now finds herself in a peculiar position of campaigning for the very thing she so strongly opposed.

The Vote Leave campaign was engaging and omnipresent, while Remain was so certain of victory that their campaign came across as tepid and insipid. Nothing about keeping the status quo could excite the electorate, less so given the lacklustre campaigning and downplaying of the EU’s good points. Vote Leave also provided a platform for ambitious ministers to showcase their talents. As far as Boris Johnson was concerned, the Leave campaign was the perfect opportunity to demonstrate his leadership capabilities, ready for him to step into the role of Prime Minister, post-Cameron. Because the Leave vote could seemingly never pass, there would be a period of years where Boris’s unlucky campaign could be put behind him and remembered as a valiant attempt. The following achievements by Johnson could be added to the showreel, and by 2020, he would have demonstrated himself as the Conservative Party’s natural, and most electable, choice.

After the votes had been counted, Johnson was strangely silent. He has been rather quiet for the last 11 months or so, in spite of being made Foreign Secretary. However, that is probably for the best given his past gaffes regarding our overseas friends. The Leave victory was something of an embarrassment for him—he didn’t really believe in it either, it was only meant to be for show! It seems like none of the Tories really wanted this to happen. But happen it did, and the feeling was that there was more to be gained by proceeding down that route than to lose face and risk UKIP gaining even more territory. David Cameron’s position became untenable, and he resigned not only as PM, but also as an MP. A vacancy opened up, but who wanted to be shortlisted for that job? Here was Theresa May’s chance to snatch the reins of power. Up against only one (extremely weak) candidate, it was simply a matter of procedure. Finally, we had a vote that went the way it was supposed to.

May’s cabinet reshuffle was brutal. Leavers and Remainers were ousted, mainly those demonstrating anything resembling charisma. It was true a Cabinet moulded in her image, with the aim of eliminating all threats to her leadership. She said she just wanted to "get on with the job", and this can be done efficiently by removing any dissenting voices. Malcolm Rifkind, a former Cabinet Minister under Margaret Thatcher, was impressed at May's ruthlessness. Now that is some accolade. For an ex-Remainer, she was very keen to champion “the will of the people” and send us down the route of invoking Article 50. This went against everything she had said on the matter before the referendum, but sometimes one must make these little sacrifices in order to cement one’s position. Who needs principles and integrity anyway, especially when they get in the way of power?

May was sitting on a majority of seats in Westminster, but she craved more. A larger majority would increase her authority and give her the mandate she so badly needed to ensure she could not be ousted. And so, in mid-April, a general election was called. On the face of it, it seemed a smart move: there was virtually no way that the Conservatives could lose, and so they had everything to gain. However, the last year has been full of surprises, politically speaking, and things didn’t go to plan. While the Conservatives didn’t lose the election, they didn’t quite win it either. As we edged closer to polling day, we could see the fear on Theresa May’s face, when she actually decided to turn up in public. During her absence, the cracks in her government were appearing, and the election result forged them into great chasms. Her party failed to secure an overall majority, having made a net loss of 13 seats against a gain of 30 seats by Jeremy Corbyn’s rejuvenated Labour party. This left May looking really rather silly, and in need of a few favours from other parties.

Feeling the heat, Theresa May was quick to mention that the country needed “a period of stability” to form a government, which sounds like a desperate cry to not replace her as leader. Not that she need bother because it’s becoming clearer by the day what a poisoned chalice it is. Whoever becomes Prime Minister after all this will either need to push through a divisive and damaging Brexit or turn everything on its head and go begging to the European Parliament for clemency. All that alongside healing the wounds of austerity and uniting a fractured Britain.

To form a majority, the Conservatives needed to find allies from another eight seats. The Democratic Unionist Party have always been closely aligned with the Tories, and they now hold ten seats in Westminster. This seemed the obvious and most convenient choice. But politics in Northern Ireland is very different to that of mainland UK. The DUP are only represented in NI, and their brand of conservatism is not to the taste of those across the Irish Sea. A number of sources have revealed some of the DUP’s less progressive policies (e.g. on equal marriage and abortion rights), which are problematic in themselves: how can we uphold the Equalities Act if we have elected ministers who are radically opposed to it (the Equalities Act 2010 does not apply in Northern Ireland, as their equality legislation is a matter for the devolved Northern Irish government, and separate from the laws that apply in mainland Britain)? Nevermind, this is what is needed to ensure Theresa May’s position. We can negotiate later; let’s not let those annoying rights and principles get in the way of strength and stability.

But then, something far more serious came to light. Some of us still remember what was referred to as The Troubles, which in reality was a civil war on our own doorstep. And it only ended 19 years ago. The fighting between Republicans and Unionists had gone on for thirty years and was only resolved through peacekeeping efforts and diplomacy. The result was The Good Friday Agreement, a historic piece of legislation that came about through uncomfortable compromises from all sides. But most importantly, it brought peace to Northern Ireland (former PM Sir John Major is very angry about this proposed coalition—years of negotiation, concessions, and many lives lost went into securing peace in Northern Ireland, and now that is all in jeopardy). One of the key conditions holding that peace together is that the UK government has an impartial presence in Northern Ireland, something that we do not have if the DUP is part of a governing coalition with the Conservatives. In addition to that, the idea of power-sharing is broken down with a DUP majority, especially since they were the only political party to oppose the Good Friday Agreement.

In 2015, the DUP compiled a wish-list, in preparation for a possible coalition in the event of a hung parliament. The election was won with an overall majority, so this never came to be. But it's worth taking another look at that list, even though the DUP have said that they will not bring sectarian matters into Westminster:

- Protection from prosecution for Security Forces involved in collusion [with loyalist paramilitaries]

- Right to fly the Union Jack flag more on Public Buildings

- More rights for the Orange Order to march

- Removal of Sinn Fein funding for Westminster Offices

- Exclude Republicans previously involved in violence from designation as Victims

(Source)

Even though these items are out of the negotiations, the sentiment behind them is still strongly felt. Just days ago, the Orange Order petitioned the DUP to allow them to march through a symbolically Catholic area. The fact that the request was even made in the first place is inflammatory, and a message that the Unionists are staking out their territory. This can only end badly, as it has done so many times over the last 50 years.

The question of Northern Ireland had come up before, in relation to Brexit. The Irish border is something that no-one in government has addressed yet. How would it be enforced, and what would that border mean? Leaving the Single Market complicates things, as checkpoints would be necessary, and minor roads could form a route for smuggling and illegal immigration. Such a border may inflame divisions, as it would provide a tangible divide between the British territory and the Irish. A “soft” border leaves more unknowns: while that is essentially the situation we currently have, it would mean free movement between The Republic and the UK, which is one of the first things that Brexit is concerned with abolishing. It seems that whatever the government does, it cannot get it right on this delicate issue. Of course, if they hadn’t risked it all on an opinion poll in the first place, we wouldn’t be in this mess.

Speaking of the mess we’re in, Theresa May says that she got us into it, and she will get us out. Recent evidence suggests that this not is the wisest idea and that it is unlikely to work. But it’s another excuse to grip on to power by her fingertips. Conveniently no-one from the Conservative Party has stepped forward, and I don’t blame them. The country is in a terrible mess, and the only way to fix it is to admit our mistakes and follow a different path. That is a very big piece of humble pie to swallow. But Theresa May is stubborn; “a bloody difficult woman” as she said of herself. In her role as Home Secretary, that attitude served her well. But a Prime Minister needs diplomacy and wisdom, not sheer bloody-mindedness.

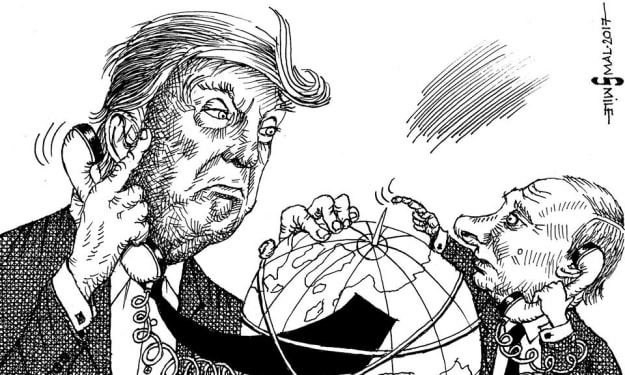

So here we are. We have strength and stability, but we don’t actually have a government. The compiling of the Queen’s Speech to Parliament has been delayed, firstly, and fantastically, by the ink needing more time to dry on the goatskin vellum; and secondly, more truthfully, due to the ongoing negotiations with the DUP. We heard those words “Strong and Stable” so many times during the campaign. They didn’t lose their meaning through repetition because they never really had any. But now we know. Strong and stable is what Theresa May aims to be. The strength and stability of the UK economy, the UK itself, and peace in Northern Ireland are a mere afterthought to her. Strong and stable, and immovable. What else will she sacrifice in the name of “strength and stability”?

About the Creator

Katy Preen

Research scientist, author & artist based in Manchester, UK. Strident feminist, SJW, proudly working-class.

Enjoyed the story? Support the Creator.

Subscribe for free to receive all their stories in your feed. You could also pledge your support or give them a one-off tip, letting them know you appreciate their work.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.