Storytelling as Mind Control

Everything is propaganda if you break it down.

Propaganda can be an insidious beast.

The most ironic object I own is sitting next to me as I write this. It's an article I picked up for $6 in a bookstore in central China - a copy of George Orwell's 1984, fully translated into Chinese. Within these pages is a classic tale of a government worker tasked with the annihilation of any information that might run contrary to the tale spun out by Big Brother, now available in a real-world nation that has made the machinations of Minitrue seem almost quaint.

I lack the proficiency to read this edition of the book and it's unlikely I'll ever be able to do anything more than pick out a few well-known passages, but I keep it here as a reminder of a key point: Our common understanding of censorship is excessively limited.

Censorship is a fact of life in China, and an especially aggravating one. Perhaps that sounds trivial to you - we're supposed to talk about censorship in much more apocalyptic terms than this. As is so often the case in life, the truth is much more mundane than bad fiction might have you think. Live in a world of controlled media, and that control becomes less an abuse of power and more a day-to-day aggravation to cope with - something like bad weather or, more relevantly, an awful piece of DRM.

It's not the narrative you usually get from the Western press - you know what I mean, the one in which the lone intrepid voice in the wilderness bravely defies the autocrats to report on the suffering of a fearful oppressed populace. Feel free to picture me as a crusading hero if that makes this more compelling.

Mastering the Narrative

There's nothing new about censorship, especially here. The First Emperor's campaign against Confucianism - now known as the "Burning of Books and the Burying of Scholars" - was, if not the first instance of book burning in history, certainly the first of its scale. Ever since, there's been a simple understanding among despots the world over. If an idea threatens your order, then find that idea - in a book, a building, a person - and put a torch to it.

I'm saying "ideas," but a better term might be narratives. Contrary to popular reckoning, the facts never speak for themselves - a fact can't say anything other than its own name. A fact gains meaning when it is linked to other facts and these links are interpreted. This is the narrative, and it's how humans think about nearly everything in life. We tell ourselves stories to understand how the world works.

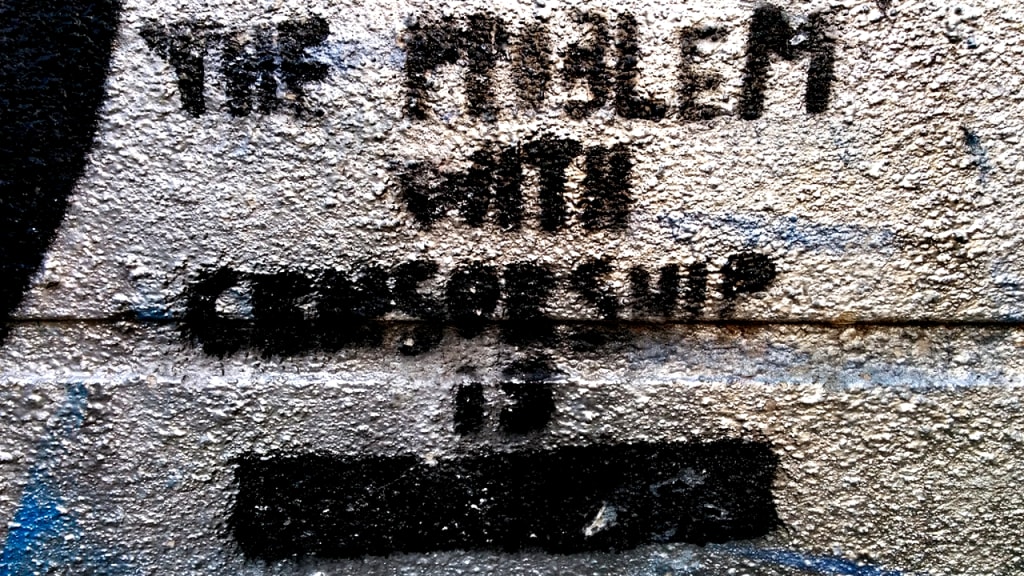

Censorship is one approach to a dangerous narrative, and has been a favorite for thousands of years. The most direct approach is to destroy the facts that comprise that narrative. It's easily done, but isn't terribly stable. After all, you can't truly destroy a fact -look to the First Emperor, there have been few who tried as hard. All you can do is conceal a fact, and if your subjects uncover an inconvenient fact, they're going to be all the more suspicious of why you spent such effort hiding it.

There's a second type of censorship, one that's much more subtle - narrative control. You leave the facts where they are and instead seize control of the story that makes it so dangerous. Governments have a long history of this as well, but most historical rulers did nothing more than exploit traditional narratives that were already there. Again, it's a simple tactic - find an in-group and exploit their preexisting fears, biases and rivalries so that they spend their time hating someone besides you.

Times change, and the more sophisticated tyrants of the modern age have tools and techniques to truly master narrative, to shape it or even create a new one from nothing. If a government (or any big organization) wishes to master the narrative, they now have a number of approaches. Censorship can be part of it - it's easier to tell a story if information that contradicts your story is invisible. At the other end, a narrative may be propagated through disinformation, the fabrication of false facts.

The beauty of this tactic, though, is that coarse trickery like this isn't required. You can master the narrative without resorting to such naked subterfuge - all you really need are some basic storytelling skills and knowledge of history and psychology.

The Memory Hole Lays Idle

I'm describing what's usually called propaganda. It's that favored snarl word for any idea that's not mine and I don't wish to engage with. It's never been an especially well-defined term - we know propaganda when we see it, or so we tell ourselves. Part of our own prevailing narrative in the West is that we're too rational and worldly to fall for propaganda. It's this thinking that makes us vulnerable to it.

Propaganda is not merely related to censorship, but is an extension of the same. What we usually call "censorship" is perhaps best termed external censorship, an attempt to master the social narrative through some tangible means - whether that's a lit torch or a memory hole or a DNS poisoning routine. Propaganda is internal censorship. Properly executed propaganda creates a "censor" inside the subject's mind, and this is far harder to dislodge.

The effect of this internal censor is such that external censorship becomes unnecessary. Earnest belief is resistant to things as feeble as persuasion or rationalism. If a person buys into the dominant narrative, and he is exposed to information that would tend to support an alternative narrative, then he's not going to change his mind. He'll resort to a handful of tactics - he might create a counter-narrative that explains the fact away, or question the veracity of the fact, or ignore the fact and launch accusations at the person who raised it, or perhaps all three in sequence. What's more, the internal censor will drive him to prefer information that confirms the narrative and avoid other narratives entirely - he creates his own form of external censorship without government action.

George Orwell gets a lot of justified praise for the world he constructed, one which features some very famous scenes of propaganda and narrative control. However, he still posits that this internal censorship requires external censorship in order to prevent the facts from spoiling the narrative. In real life, it's not necessary. There's no need for a Memory Hole, no need for Newspeak, no need for any narrowing of the discourse. A citizen who understands how the world works will eagerly disregard anything that would suggest otherwise, and damn the liars who would even say such things.

The Censor Within

So why bother with external censorship at all? It could be fear that what I've suggested won't always be true. It could be that there are reasons to practice censorship beyond hiding inconvenient facts - China's use of censorship for purposes of digital protectionism and cultural preservation are often overlooked.

There's another Western trope in which the benighted, tyrannized citizen of the dystopian state learns the truth and immediately adopts all American values. Of course, "truth" is, itself, a narrative. The government here heavily censors foreign news save that which directly impacts China, and when Chinese people gain access to the domestic news of the U.S., for example, the response is different than what you're used to seeing in bad novels.

In my experience, at least, they're a lot more likely to conclude that the Western world is far more chaotic than they ever thought. They see Americans throwing a fit over masks, even as more and more people get sick. They see rioters burning buildings and attacking the police, while media figures beseech the world to negotiate with the rioters. And then they see politicians screaming about being "tough on China," and trying to hurt Chinese companies, and spreading the most awful lies, and many of them conclude that our system is broken and we're scapegoating China to explain away our own failures.

So yes, I've observed this dynamic firsthand…but so have you, I'd wager. No doubt you've been thinking about it as I've been describing it. Storytelling is a kind of mind control, and the only counter is the story we tell ourselves. You've probably been thinking of your nutjob neighbor and his deranged beliefs. It's unlikely you saw any of your friends and well-wishers in here. You definitely didn't see yourself, but provided that you are human (or even a machine designed by those with human sensibilities), you're susceptible as well.

Bringing this full circle, one area I've seen this is when I talk to Americans about China. I've had people ask me if I'm afraid of being killed by the government for writing things like this. When I say no, they assume I'm lying - I've been threatened or paid off. After all, everyone knows what the PRC is like, everyone knows the truth, so anything contrary to that truth must be a lie. And there's that censor between your ears doing his work.

Tyranny Over the Horizon

Thus, we see the power of internal censorship and its many advantages over external censorship. Propaganda is weightless, invisible and durable. It is self-sustaining and self-propagating. It makes no demands of its hosts and, thus, is at home in any society. And no one wants to believe that he is vulnerable to its effects, which only makes it more effective.

This is the future of tyranny - and it's what makes so much of dystopian literature so comical. Dystopian writers exhibit a common lack of creativity in this regard. They all stopped their predictions with Orwell, and thus assume that authoritarianism will look the same in the future as it did in Orwell's day and before. They posit some brute force despotism, perhaps with some high-tech flair but still ultimately rule by the truncheon.

I can see a future in which dictators need not employ force at all, where there's no need for a Minitrue or a Miniluv or any other blunt instrument. They won't conceal the facts, and they'll have little need to lie. The technologies will change, but whatever scientific refinements they may have, their core technique will be the oldest one in the world:

They'll tell you a story, and you'll believe it because you want to.

About the Creator

Andrew Johnston

Educator, writer and documentarian based out of central China. Catch the full story at www.findthefabulist.com.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.