ON the theoretical impossibility of Scottish Indepedence

A voting system immune to strategic voting is a dictatorship. The UK parliament is in practice dictatorial. The system used to elect the Scottish parliament is almost immune to strategic voting but tends to stop any party gaining an absolute majority, making it unlikely Scotland can easily become independent unless English MPs desire this.

In 1785 French mathematician Nicolas Condorcet discovered problems in the theory of voting when the voters had more than two alternatives. In his examination of various voting systems he discarded the first past the post system if there were more then two alternatives, because the least popular alternative might win even if it would lose in a series of pairwise elections.

Condorcet suggested choosing the alternative that would win over all the other options in a series of pairwise elections: something like a football championship. This was the Condorcet Winner.

Unfortunately there are situations where there are more then two alternatives where there is no Condorcet Winner. This happens when, although the voters rank their preferences consistently in a transitive fashion, that is each voter can rank the alternatives in order of precedence, the overall ranking means the least favoured option wins.

To understand this lets take three alternatives, A,B,C. These are ranked transitively if A>B and B>C means A>C.. The problem is that a series of pairwise elections could result in a non-transitive result A>B and B>C and C>A) if enough voters prefer C to A.

IN 1942 when Scottish economist Duncan Black found that there was a Condorcet winner if very voter ranked the alternatives in the same way, for example if the alternatives could be priced from high to low: imagine an election fought on the price of a loaf of bread. In such a single peaked situation each voter has a preferred alternative and dislikes the others more and more as they move away from the preferred situation.

In a single peak situation the winner will be the alternative that is liked by half the voters and disliked by the other half (those who make money selling bread will like the higher prices).

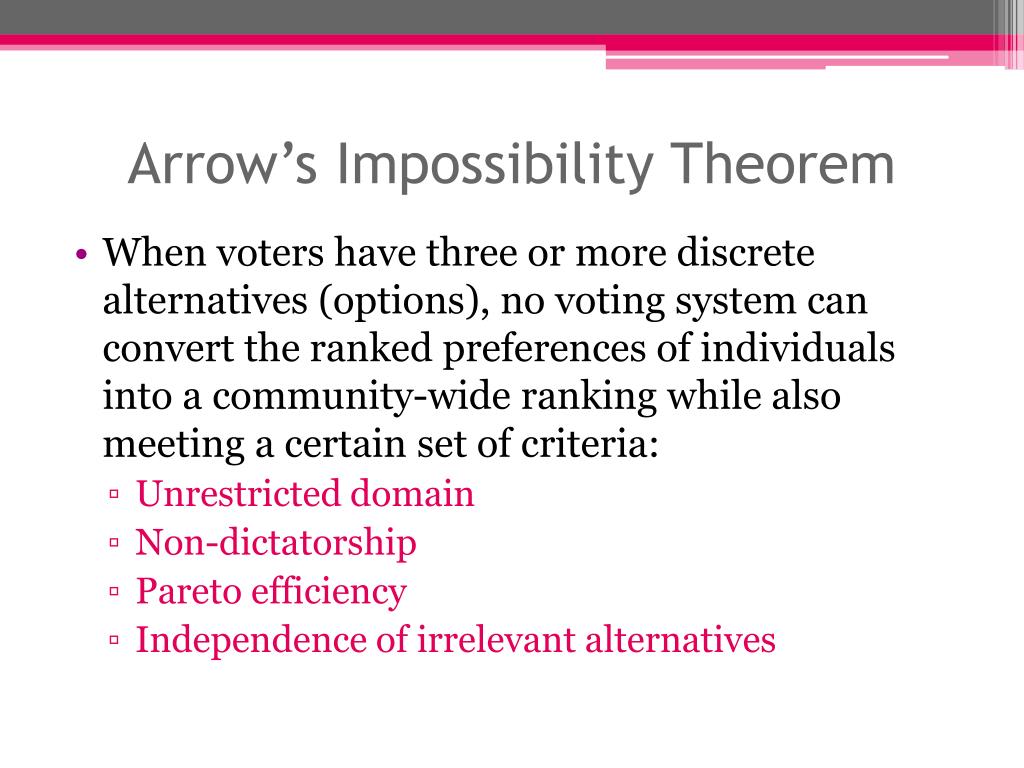

In the 1940s Kenneth Arrow adopted the well known tactic of changing how the problem was investigated. Instead of examining possible voting systems, as others had done, he laid down five plausible conditions a good voting system must obey and showed that no voting system could satisfy all five. Since it was unacceptable to drop any of the conditions this caused something of a stir.

Other mathematicians failed to find alternative rules for a perfect voting but they all found a contradiction. It seems there is a problem with the very notion of voting when there are more than two options – and in any election, even with just two candidates, for example in a referendum, voters have the options of not voting or spoiling their voting paper, a default “none of the above” vote. Most governments assume that those who do not vote are indifferent to the outcome and a small number of spoilt papers can be ignored.

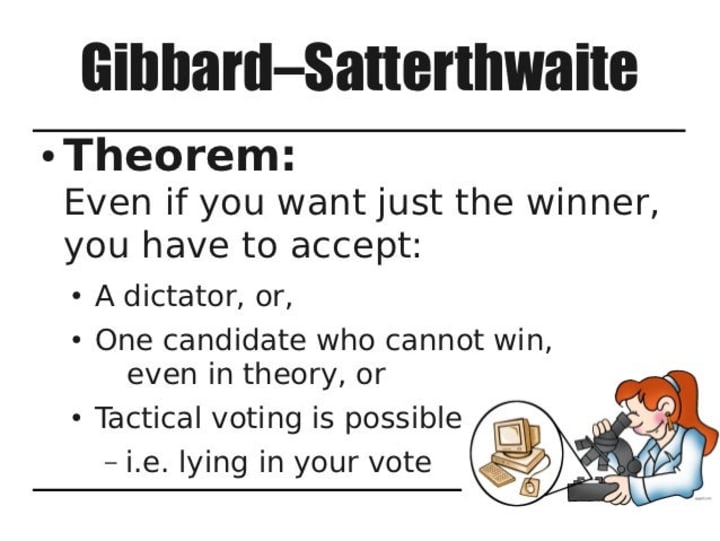

A theorem by Gibbard and Satterthwaite (The GS theorem) later tackled the problems of strategic voting and the problem of the “Dictator” an individual ( or group) that gets what they want regardless of the way any one else votes ( A dictatorial system). The theorem concludes that if there are more than two alternatives then a system that is not manipulable is dictatorial. And a dictatorial system is unacceptable in any society that considers itself democratic.

Moving away from theory into the real world where the voters can be influenced by biased news presentation and propaganda it is worth considering the UK.

In England which has the largest number of votes in the UK parliament, safe seats, those where one party has overwhelming support are effectively dictatorial. The support has been known to waver in the remaining, marginal, seats forcing the largest party (which is usually not the most popular) to form a coalition with a minority party in order to implement at least some of its policies. Nevertheless, the UK prime minister acts as a dictator as long as they can command a majority in the House of Commons, which means it is very unlikely the UK parliament will support Scottish Independence unless the English MPS, in particular the MPS of the largest party, actively wish it ti come about.

In Scotland a more complex system is in use that is hard to manipulate and makes it hard for any party to gain an absolute majority in the Scottish parliament but makes it theoretically possible for minor parties to be represented in parliament. This means for example that the SNP is unlikely to gain enough seats and votes to declare independence for Scotland.

Conclusion

There is no perfect voting system and the systems in use in England and Scotland make Independence unlikely unless voting intentions can be swayed towards independence in both countries. A larger swing toward independence is needed in Scotland than has currently been achieved. The good news is that if such a swing can be achieved Independence is almost guaranteed.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.