How Switzerland became keeper of the Templar legacy

Banking on a future of mercenary service

When Ignatius of Loyola became the first "Father General" of the Society of Jesus (Jesuits) in 1540, he did so in a very different-looking continent than Europe appears today.

Pope Paul III, who approved the society’s foundation within the Catholic church, had his home in the Papal States, which existed in the northern half of the Italian Peninsula, sandwiched between the Kingdom of Naples to the south and the Holy Roman Empire to the north, with which it enjoyed a complicated relationship. For all intents and purposes it was a part of the Frankish empire, but in their realm the popes enjoyed absolute control.

To the east, around the Adriatic coast, the Papal States bordered the Venetian Republic, as did the Kingdom of Naples across the Adriatic (with Hungary and the Ottoman Empire further to the east and the Kingdom of Sicily to the west).

The Holy Roman Empire, the most powerful monarchy on the continent, comprised of Flanders, Brandenburg, Silesia, Bohemia, Lorraine, Bavaria, Franche-Comte, Savoy, Austria and the Swiss Confederation. To its west was England, France and Spain, plus the smaller territories of Scotland, Ireland and Portugal; to the east there was the Kingdom of Poland, Grand Duchy of Lithuania, Kingdom of Hungary and the Ottoman Empire; while to the north were the kingdoms of Denmark, Norway and Sweden.

Already that sounds complicated enough, but it was a time of much conflict in Europe and great change, with the actual picture being even more confused than this potted history of the power bases. But the area to focus on for the purposes of this article is the Swiss Confederation.

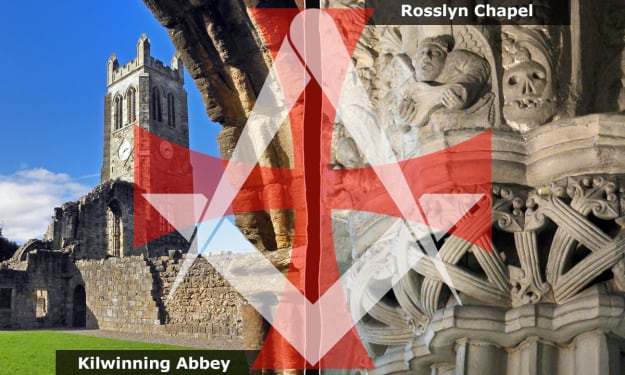

While the Jesuits began their quest to spread Catholicism to the world and harness the vast resources of South America, Asia and the Pacific... their predecessors, the Templars, had their eyes firmly fixed on the Swiss Confederation which, like Scotland, was believed to have been a safe haven for followers seeking refuge from persecution in France two centuries earlier.

Long before 1312 – when the Vatican disowned the order after a merciless crackdown on followers in France in 1307 as a result of accusations by King Philip IV about the order’s “sexual deviation” – the Templars had earmarked the complex patchwork of cantons in the foothills of the Alps as a place of refuge if things turned sour.

The cantons were the scene of frequent conflict, which the Templar knights were comfortable with and could capitalise on, but they also provided a convenient location for their followers to pursue their other talents for banking and finance, with the rest of the Holy Roman Empire, Venetian Republic, Hungary, the Ottoman Empire and Scandinavia all potential targets for their expertise with money.

The original confederacy was an alliance among the valley communities of the central Alps governed by nobles and patricians of various cantons who ensured peace on mountain trade routes. But, by 1353, the three original cantons – Unter-Walden, Uri and Schwyz – had joined with the cantons of Glarus, Zug and the Lucerne, Zurich and Bern city-states to form the "old confederacy" of eight states through to the end of the 15th Century.

This expansion led to increased power and by 1460 the confederacy controlled most of the territory south and west of the Rhine to the Alps and the Jura mountains.

Military victories against the Habsburgs (Battle of Sempach and Battle of Nafels) during the 1470s also enhanced a reputation for soldiering, with “Swiss mercenaries” highly valued throughout the kingdoms of Medieval Europe. Hiring their services was made even more attractive because entire contingents could be obtained by contracting their canton governors, who operated a militia system in which the soldiers were bound to serve… and trained and equipped to do so.

The eight cantons gradually increased their influence on neighbouring regions through alliances, including pacts with Fribourg, Appenzell, Schaffhausen, the abbot and the city of St Gallen, Biel, Rottweil, Mulhouse and others. These allies, known as the Zugewandte Orte, became closely associated with the confederacy, but were not accepted as full members.

The Burgundy Wars prompted a further enlargement of the confederacy with Fribourg and Solothurn accepted in 1481. Then, in the Swabian War against Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian I, the Swiss were victorious and exempted from imperial legislation with the associated cities of Basel and Schaffhausen joining the confederacy as a result, and Appenzell following in 1513 as the 13th member.

The federation of 13 cantons (Dreizehn Orte) constituted the old Swiss Confederacy until its demise in 1798 but conflict during the Reformation in Switzerland led to division amongst the cantons and civil war – the Wars of Kappel – when the Catholic and Protestant factions reached separate alliances with foreign powers, although the confederacy as a whole continued to exist while a common foreign policy was blocked by the impasse.

During the Thirty Years' War (1618-48) in central Europe, religious disagreements among the cantons kept the confederacy neutral and at the Peace of Westphalia, which ended the conflict, the Swiss delegation was granted formal recognition as a state independent of the Holy Roman Empire and its “neutrality” as a nation was recognised.

But growing social differences led to localised revolts resulting in the Swiss peasant war of 1653, which was put down swiftly with the help of many cantons. But the religious differences were confounded by a growing economic void… the predominantly rural Catholic central-Swiss cantons surrounded by Protestant city districts with stronger commercial economies.

An attempt (led by Zurich) to restructure the confederation in 1655 was blocked by Catholic opposition and led to the first battle of Villmergen, in which the Catholics prevailed to cement the status quo, but friction persisted and erupted again in 1712 with the second battle of Villmergen. This time the Protestant cantons won to dominate the confederation but true reform proved impossible… the individual interests of the 13 members proving too diverse.

But the next chapter – the Napoleonic era – in the rise of modern Switzerland changed all that. In 1798 the revolutionary French government of Napoleon Bonaparte invaded Switzerland and imposed a new unified constitution which centralised the government, effectively abolishing the cantons.

The new regime, known as the Helvetic Republic, was hugely unpopular since the invading foreign army destroyed centuries of tradition, making Switzerland nothing more than a French satellite state.

Later, when war broke out between France and its rivals, Russian and Austrian forces invaded Switzerland. The Swiss refused to fight alongside the French in the name of the Helvetic Republic so in 1803 Napoleon organised a meeting of the leading Swiss politicians in Paris that resulted in the Act of Mediation, which largely restored Swiss autonomy and introduced a confederation of 19 cantons, the six accessions being former associates and subject territories including St Gallen, Grisons, Aargau, Thurgau, Ticino and Vaud.

Three additional western cantons, Valais, Neuchatel and Geneva also acceded in 1815 when the Congress of Vienna fully established Swiss independence, with the European powers recognising permanent neutrality, although Swiss troops served foreign governments until 1860 when they fought in the siege of Gaeta, situated on the Mediterranean coast between Rome and Naples.

By 1830 most of the former feudal rights of the Swiss patriciates had been restored which fuelled rebellion in the rural population with calls for a new federal constitution. This tension, coupled with religious issues, escalated into armed conflict in the 1840s, with the brief Sonderbund War resulting in the formation of Switzerland as a federal state in 1848.

The war actually lasted less than a month and caused less than 100 casualties but it had a profound impact, convincing most Swiss of the need for unity and strength. So, while the rest of Europe saw revolutionary uprisings, the Swiss drew up a constitution that provided for federal government, largely inspired by the American example.

This saw the cantons retain far-reaching sovereignty but they were no longer allowed to maintain standing armies or international relations. It provided central authority, while leaving the cantons the right to self-government on local issues, while effectively ending the legal power of the nobility in Switzerland.

Cantonal armies were converted into the federal army (Bundesheer), with every Swiss citizen required to serve (Wehrpflicht) in the federal army.

As well as being the birthplace of the Red Cross, one of the world's oldest humanitarian organisations, Switzerland today hosts the headquarters or offices of most major international institutions, including the United Nations, the World Trade Organisation, the World Health Organisation, the International Labour Organisation and the World Economic Forum.

It is a founding member of the European Free Trade Association (EFTA), but not part of the European Union, the European Economic Area, or the Eurozone; however, it participates in the European single market and the Schengen Area through bilateral treaties. It is also the home of the Large Hadron Collider (LHC), the world's largest and highest-energy particle collider, built by the European Organisation for Nuclear Research (CERN), that occupies a tunnel 27 kilometres in circumference beneath the France-Switzerland border near Geneva.

In addition to its reputation as Europe’s pre-eminent banking centre renowned for its “discretion” in financial matters, Switzerland is also the home of many of the world’s leading pharmaceutical companies with about 30 per cent of Swiss exports (worth US$84.8bn) in 2017 being chemical products, when it was also the world’s second largest exporter of packaged medicine, with about 11 per cent of the global market worth US$36.5bn.

In 2013, 41 life-science companies were headquartered in Switzerland (29 more having their regional headquarters there), with Novartis, Hoffmann-La Roche, Alcon and Bayer leading the way.

Swiss neutrality and its national sovereignty, long recognised by foreign nations, have fostered a stable environment for the banking sector to develop and thrive, with Switzerland maintaining neutrality through both World Wars. Basel provides the headquarters of the Bank of International Settlements (BIS), founded in 1930, which facilitates cooperation among the world's central banks.

So, what’s the lesson of this story? Well, could it be that after 1312 the Templar knights fled to the Swiss Confederation where they developed a militia system supplying mercenaries for conflicts across Medieval Europe, that continued into the 19th Century, and transformed a hodgepodge network of feuding cantons into an independent federal state with a banking system that has brought them influence beyond their wildest dreams? Now, I don’t know about you, but I think there’s pretty good evidence to support this hypothesis!

About the Creator

Steve Harrison

From Covid to the Ukraine and Gaza... nothing is as it seems in the world. Don't just accept the mainstream brainwashing, open your eyes to the bigger picture at the heart of these globalist agendas.

JOIN THE DOTS: http://wildaboutit.com

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.