Hart and International Law

"Hart never said international law was not law because it did not have secondary rules (and was thus unlike state law). Instead, he pointed to the limits of understanding international law on an analogy with state law."

Introduction

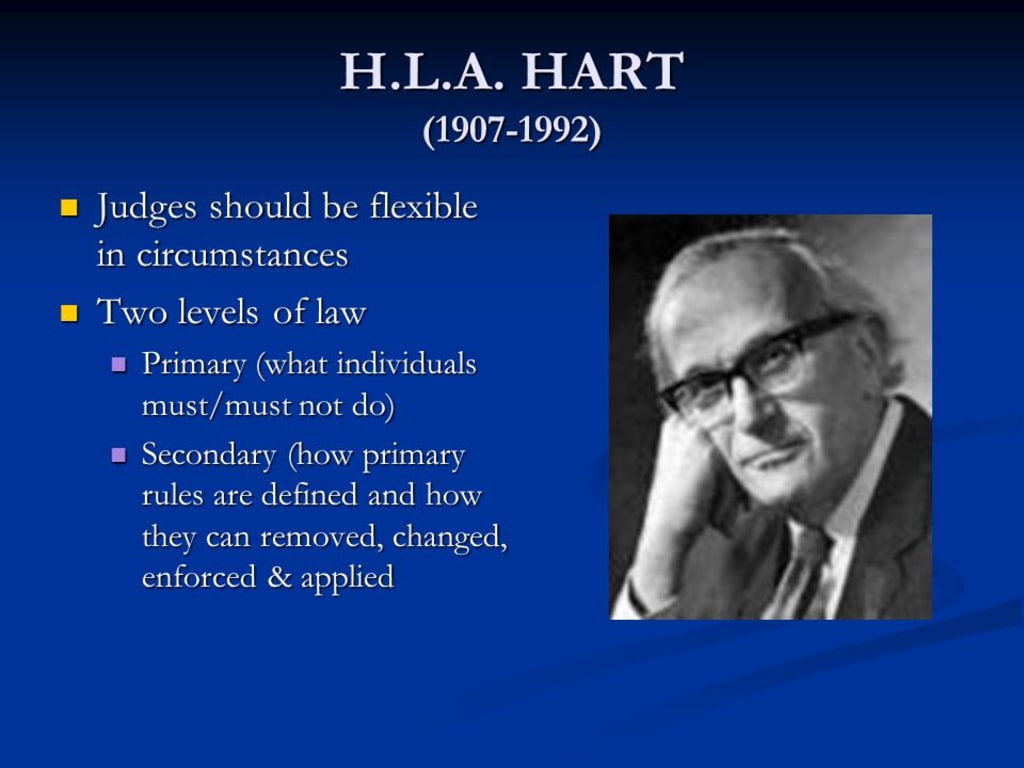

In chapter 10 of his The Concept of Law, Hart asks whether International Law is genuinely law or is it better seen as international morality? He argues that international law is law, but different in some important aspects from state law.

Why are there arguments that international law is not law not successful?

What are the arguments for asserting that it is law?

Hart’s main sources of doubt concerning the legal quality of international law appear to be: that there is an absence of an international legislature, of courts with compulsory jurisdiction, and centrally organized sanctions.

According to Hart, international law resembles a "simple form of social structure" found in primitive societies.

For Hart, international law consists mainly of primary rules, and he expresses doubts whether any secondary rules exist on the international level.

What is International Law According to Hart?

International law threatens the account of law as Hart has theorized. There is no legislature and no compulsory jurisdiction and its rules [of states] seem only to consist of primary rules with no secondary rules. And international law appears to have no rules of recognition—so we must ask whether international law is really law?

Two problems arise:

- Attempts to analyze international law as rules backed by threats; and

- Problems that arise from believing that states cannot be the subjects of international law.

The first question is whether international law can be obligating. This is not a question of applicability but a question of whether international law is law at all. Thus the question is not analogous to the question of whether municipal law is really law and Hart denies that we can claim that international law is not binding because it has no organized sanctions because to do so would be to accept Austin's view.

However, we might ground law in the need for such law to resolve international disputes, as international aggression is the most dangerous sort. Under international law, many world nations have rights and duties and are subjects of the law.

What does it mean for a "sovereign" state to be "bound" by law?

Some skeptics feel that this is meaningful because sovereignty only denotes that someone is sovereign over a territory and those who live within it; the definition does not rule out sovereignty over it with respect to other sets of matters.

Another difficulty with this view is that we cannot define state sovereignty without first knowing what international laws they are subject to and some may argue that real international obligations do not exist except by voluntary agreement.

International law and morality are tied in complex ways; since international law is like a system of primary rules, we might use moral rules of recognition to identify it since legal secondary rules do not exist.

However, Hart resists this view on the grounds that different states recognize different moralities and are often hypocritical in their advocacy of moral demands. Many rules of international law are not obviously moral but practical. International law also must specify details that are non-moral, such as how long a treaty is binding.

Hart argues that it is unclear whether international law, to exist, must rest on moral obligation and resists some analogies of form and content between international law and other forms of legal rules. Accordingly, Hart encourages us to liberate ourselves from requiring that international law must contain a basic rule because the rules of international law fit very different social situations and so it is hard to see that they can allow a simple analysis or simple analogy with other forms of law.

He sums it up by stating: Until basic rules of recognition are formulated, international law can be seen as at most a system of transition to secondary rules, although it seems clear that it exists as a set of primary rules—the only analogy between international law and other law is of content and in content the rules are closest to international law than any other form of law.

Are International Laws Moral?

Hart rejects the argument that international law is understood as international morality. Arguing that states distinguish between moral and legal appraisal in evaluating each other’s conduct and that rules of municipal law and those of international law are often times morally mediocre.

There are, however, arbitrary differences which cannot be explained by moral standards—given that legal formalism is a characteristic of international law that does not agree with characteristics of morality and unlike rules of morality—rules of international law are subject to deliberate change.

A moral foundation is not necessary to explain the binding force and obligatory character of international law. It is necessary; however, that the rules of international law are generally followed—there are a variety of reasons why states obey their obligations. A moral obligation to abide by international law may be one of the reasons—but there is no gripping reason why it has to be a necessary feature of international law.

An International Justice System?

Hart’s insistence that international law does not constitute a legal system seems almost as problematic as Austin’s insistence that international law is not law at all. Although, Hart emphasizes that international law is law—one is tempted to form the impression that Hart, like Austin, did not believe there was any such thing as international law.

Hart, does not pretend to develop a comprehensive theory of international law but concedes that the integration of international law—and other "borderline cases"—into his jurisprudence is of only secondary concern to him.

He does not analyze the structure of international law in great depth—limiting him to general remarks about the peculiarities of the international system.

Conclusion

In view of Hart’s general concept of law, the concept of international law as a legal system, consisting of secondary rules of recognition, change, and adjudication, does justice to the term "international law" as we know it.

Hart claims that international law cannot be regarded as a legal system because of the differences between municipal law and international law, to include: the lack of an international legislature, judiciary, with central sanction power, and absence of a uniform rule of recognition.

Differences between the two legal systems justify a conceptual distinction. However, they do not disprove the conception that international order is founded on an international legal system, just as the national form or constitution—as in the U.K.—is governed by a municipal legal system, exemplified by Acts of Parliament, Delegated Legislation, and Rules of Local Authorities.

About the Creator

Jim Gilliam

I was born in Velasco, Texas a small town on the Gulf Coast and raised in the even smaller town of Port Isabel, Texas. Like the protagonist in my first novel I ran away from home, lied about my age, and joined the Coast Guard at 14.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.