Confronting my White Privilege with Ava DuVernay

Black in Business

I have always considered myself a fairly liberal person.

Politically, I lean towards the left, believe in the importance of social equality, and - although I am not ignorant of the economic costs involved - I do think that being able to access education, healthcare, and legal support are basic human rights.

As is the right to live your life free from discrimination.

In addition to a passion for mental health, I also have an interest in environmental issues, and support sustainability in all of its forms.

And, despite the circus that accompanied the last US Presidential Elections, and the giant, steaming mess that was Brexit, I am an ardent advocate of democracy: It is a flawed system, but I cannot think of a fairer one.

So, yes - I am pretty liberal.

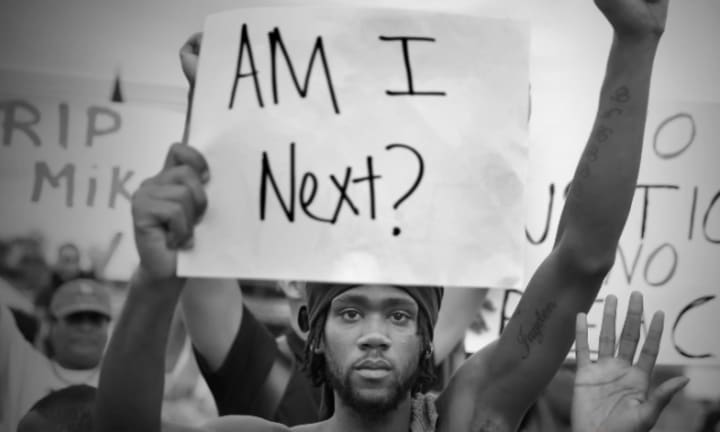

At least, I thought I was. Because then Black Lives Matter happened. And, as it turned out, I might have clearly been a liberal, but I was also a fairly ignorant one.

Worse, I was a lazy one.

To begin with, there was no issue. Of course black lives matter; I didn't need to be told that. I was happy to sign petitions, and turn my social media profiles black to show my support. And to everyone I knew who responded with the words, "All lives matter," I was fine with trying to explain why - yes - although all lives do matter, it's black ones we're talking about right now.

Easy.

And then I found myself trying to defend BLM protesters in the English city of Bristol who - on Sunday 7th June 2020 - tore down a statue of Edward Colston, and threw it into the harbor.

The only problem was that I didn't know enough to really offer much of a defense. My response was vague at best.

To be honest, not coming from Bristol, I didn't even know why this statue had been targeted.

Although I initially balked at the way this historical artifact had been disposed of, as I believed in BLM, I naturally took the stance that there was probably some justification (told you I was a lazy liberal). Also, there was an inevitable knee-jerk reaction from those on the Right; given my own natural political bias, my innate reaction seems to be to automatically take a stance opposite to such people. If they had an issue with it, then I didn't (strike two for my lazy liberality).

However, I quickly realized that none of that would suffice. Everyone was suddenly talking about Colston, and the connection to BLM; if I wanted to join in, it would help if I knew what we were actually talking about.

Quickly, I was able to discount the noise from the Right. This was a straightforward case of vandalism, they'd preached. And one that disrespected the memory of a man who had bequeathed huge sums of money to the city. That last fact cannot be denied; without Colston's donations, Bristol would look a vastly different city.

The only problem, which those who fixated on the statue's removal paid less attention to, was that that money was earned from slavery.

From 1672 to 1689, Colston's company transported more than 100,000 slaves from West Africa to the Caribbean, and the Americas. The slaves, which included women, and children, were branded on the chest with the company's initials, and then crammed into ships; the more slaves each ship could carry, the greater the profits. However, such was the overcrowding, that dehydration, dysentery, and scurvy were rife: Over 20,000 died during the crossings.

And their bodies? Thrown overboard.

My opinion is that the manner in which Colston's statue was disposed of was clumsy; it gave far too much easy ammunition to those who see BLM as a unprincipled mob. When certain parts of the media are actively seeking an excuse to brand you as no more than agent provocateurs, handily giving them the required screenshots is not helping the cause.

However, at the same time, once I started reading about Colston's exploits, I became amazed that the statue had even still been on public view. 20,000 simply thrown overboard? I honestly don't care how many nice concert halls he paid for, that statistic alone is utterly indefensible.

And as for the idea that, "Oh, that was a different time... blah blah blah... you have to understand the morality of the age... yadda yadda yadda..." - sorry, no. Just no. 100,000 men, women, and children were kidnapped from their native shores, and crammed into ships, to be slaves. A fifth of whom didn't survive the journey, and weren't even deemed important enough for a burial. I can only look upon that with my twenty-first century eyes, and see nothing even vaguely justifiable about that.

And I don't appear to be alone. Because Colston's statue had been an issue of contention for some time. A petition to have it removed before its watery demise had already received over 11,000 signatures. And it's hard to fault the logic behind it:

“Whilst history shouldn’t be forgotten, these people who benefited from the enslavement of individuals do not deserve the honor of a statue. This should be reserved for those who bring about positive change and who fight for peace, equality and social unity.”

Again, I think an opportunity was missed to use the statue as a starting point for a debate that could have swayed more people than simply throwing it into the river. However, there's a much more important factor; Colston's philanthropy doesn't negate the source of his money. Sentiments echoed by the mayor of Bristol, Marvin Rees;

“I know the removal of the Colston Statue will divide opinion, as the statue itself has done for many years. However, it’s important to listen to those who found the statue to represent an affront to humanity.”

And that was what I now argued to those who took issue with the actions that day in Bristol. Should the statue have been dumped in a river? You could argue that it's poetic justice given where the bodies of Colston's dead slaves ended up. I would've preferred something different, but that's how events played out. But could I understand why the protester's anger had been fixated on Colston's statue?

Yes. Yes, I could.

It may have been an act of vandalism, but there was a reason behind it. The logic of which I understood.

However, I now had another problem; I was fully aware of my ignorance. Because it wasn't just Colston - George Floyd, Breonna Taylor... I knew the names, I could even tell you why they mattered.

But did I know enough?

No.

My lazy liberality had meant an automatic affiliation with the Black Lives Matter movement, but it was one that was superficial. To be honest, as a white man, and as someone who was not directly a victim of the discrimination the movement seeks to highlight, you could argue that was okay; simply supporting the movement was enough.

It wasn't.

It isn't.

My 'white privilege' may mean I won't be on the receiving end, but it wasn't going to be adequate if I wanted to actually make a difference. If I wanted to be a legitimate part of this debate.

Just as I had to be regarding Colston, I needed to be educated about Black Lives Matter as a whole.

A Televisual and Cinematic Classroom

Over the next few weeks, I read an inordinate range of articles. More than that, I watched an almost infinite number of TV programmes, and films. And, as I did, I started to realize one of the reasons why I'd stayed on the fringes: What I watched was painful. Uncomfortable.

Suddenly my 'white privilege' was making me feel very privileged indeed.

Even when the item I was watching appeared relatively accessible, in the current, more febrile environment, its relevance became heightened.

For instance, one of my favorite filmmakers is Spike Lee. However, for a long time, I'd admired his technical prowess, and storytelling abilities, more than I did his political views. I've always loved 'Do the Right Thing' (1989) but - until recently - I relished more how he managed to weave the different narratives of all the disparate characters together, and slowly brought each one to a climax during the course of that scorching hot summer's day, than I did respect the obvious statements he was making about race (my 'white privilege' in full operation).

It is a bravura piece of film-making. And, like the best stories, there's that wonderful paradox that at the heart of it: The more personal the story, the more specific the setting, the more universal it becomes. I grew up in a small, military town in Hampshire, England, but Lee's Brooklyn setting still feels recognizable. After all, there's the same collection of dreamers, lovers, losers, and bullies in every town or city.

However, watching it again in 2020, the film felt different. Strangely, despite being over thirty years old, it felt brand new.

The casual racism that, perniciously, grows and grows into something much more overt and threatening... the police's inability to connect with the people they're paid to protect... an incident that - fatally - spirals out of control...

Lee is still working, still making relevant films, but 'Do the Right Thing' has a bite that many documentaries that directly explore race can only dream of.

Well, except one...

'13th'

I'm not sure I've ever been made to think more.

I'm not sure I've ever had so many pre-conceptions challenged.

I certainly know that I've never been so uncomfortable watching anything as I did whilst viewing Ava DuVernay's '13th.'

The irony is that for a film that couldn't be any more relevant, it was actually made five years ago, in 2016. It has an Orwellian prescience - like 'Do the Right Thing', it's as valid now as when it was first released. I really hope it's not the case, but my suspicions are that it will remain relevant for some years to come.

The film opens with the words of Barack Obama, saying that, although the US has 5% of the world's total population, it has (frighteningly disproportionately) 25% of the world's prisoners. DuVernay then tells us why she thinks this is the case.

And, at the heart of it, is the 13th Amendment:

"Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction."

DuVernay's film argues that - despite the 13th Amendment - slavery was never really abolished: It just changed into something else - incarceration.

And, once in prison, the same system (that of being exploited for another's profit) remained.

The documentary is - roughly - divided into three parts.

The first explores the years following the abolition of slavery in the US. Except, although slavery was legally now prohibited, freedom did not come as standard. This was a period when Southern states criminalized minor offenses, and forced the - largely black - criminals to work when they could not afford to pay the fines. A time when Democrat legislators passed 'Jim Crow' laws, legalizing segregation.

All the while, the lynching of black people by white mobs was at its peak.

The arguments are sound. The 'talking heads' eloquent, and knowledgeable. But, the elements that stay with you are the real-life pictures: A huge group of white people, staring down the camera lens, whilst - behind them - suspended from a desiccated tree, hangs the lifeless body of a single black man.

Given the historical context that's been painstakingly laid out for us, such images - which weren't meaningless to begin with - suddenly resonate even more deeply.

However, going into the second part of the film, there is a ray of hope: The Civil Rights movement.

Except...

It's leaders were exiled, or killed.

Just as devastatingly, incarceration continued apace: Now there was a booming prison-industrial complex to feed, and DuVernay doesn't shirk from giving us the list of private companies that benefited from mass incarceration; in other words, that become wealthy through the financial incentivizing of criminality.

However, what is just as illuminating is the exploration of the reforms that created that complex. From Nixon and Reagan's 'War on Drugs', to Clinton's raft of crime-reduction legislation, these were all laws that unfairly targeted ethnic communities, whilst simultaneously getting you a big enough slice of the Southern vote to take the White House.

On paper it sounds like a conspiracy theory par-excellence. But, it becomes a lot more convincing when you discover that 'the Southern strategy' was an actual, genuine, political gambit.

Among all this, there are - once again - glimmers of hope. For example, Clinton, to his credit, has since recognized that his law reforms caused more harm than they did good. They haven't been reversed in their entirety, but there is the beginning of a debate about how being 'tough' on crime isn't necessarily the same as adequately tacking crime, especially not when someone - somewhere - is getting rich off people being jailed.

However, those glimmers are quickly extinguished by the ending of the film - the third, and shortest, of my rough divisions.

DuVernay closes the film with videos of fatal shootings of black people by the police. Often, we do not see the actual moment a gun is fired. But we hear it. In real-life, a gunshot sounds flat - a million miles away from the ones we hear in action movies. It's no more than a hand-clap. Dull.

But, with that unremarkable 'pop', a life has just been lost.

We've had over an hour of well-informed historians, politicians, and activists making an argument that - even if you are politically opposed to BLM - you can't ignore the evidence for. We've experienced a skillful mixture of well-crafted animation, juxtaposed with real-life footage, overlaid by a soundtrack that is both emotive, and meaningful in its own right; a devastating aural and visual onslaught that shows us - historically - black lives haven't always mattered.

All of that is powerful. Thought-provoking.

But none matches the sound of that dull, unremarkable hand-clap.

With every one, my 'white privilege' reverberated a little more loudly.

Moving Forward...

DuVernay is a talented director. Her work before '13th' is - like Spike Lee's - an electric mix. And even her rare misfires are interesting; 'A Wrinkle in Time' may have bombed at the box-office, but it's far from lacking in entertainment.

She's also a trailblazer. Few industries are not male-dominated, but there is an especially skewed bias in the film industry. Of the top 100 grossing films of 2020, only 16% were directed by a woman. Given that the odds of you even getting the chance to direct are already stacked against you, to not only do so, but to then create meaningful work is a mighty achievement.

And as a black female director? The odds shrink even further. Her advice for how others could succeed is, as expected, life-affirming, yet wonderfully simple;

"Ignore the glass ceiling and do your work. If you're focusing on the glass ceiling, focusing on what you don't have, focusing on the limitations, then you will be limited. My way was to work, make my short... make my documentary... make my small films... use my own money... raise money myself... and stay shooting and focused on each project."

She's an impressive, inspiring individual, and she'd be one to watch one anyway, especially given the current climate. One she has again tapped into with 'When They See Us', a TV series based on events of the 1989 Central Park jogger case, where five male suspects were falsely accused, and then prosecuted, of raping a woman in New York City. An event referenced in '13th.'

It's a harrowing watch. But it's another important voice in the argument that black lives matter.

And her voice has shaken this particularly lazy liberal into action. As she herself said;

"If you know all this stuff, great. Pass it on. If you don’t know it, know it."

I don't know it all yet. There's still much more for me to learn. I'm just glad I'll have artistes such as Ava DuVernay to guide me.

And, once I have, I'll too pass it on.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

If you've liked what you've read, please check out the rest of my work on Vocal. Among other things, I write about film, theatre, and mental health:

You can also find me on Elephant Journal and The Mighty.

If you've really liked what you've read, please share with your friends on social media.

If you've really, really liked what you've read, a small tip would be greatly appreciated.

Thank you!

About the Creator

Christopher Donovan

Hi!

Film, theatre, mental health, sport, politics, music, travel, and the occasional short story... it's a varied mix!

Tips greatly appreciated!!

Thank you!!

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.