The Lexicon of Street Culture

‘S’ is for Stussy, Shawn Stussy...

As the bad-boy of fashion is increasingly co-opted by the luxury market, it’s perhaps important to remind ourselves of streetwear's roots, intrinsic values, and the man whom many say started the whole thing in the first place—Shawn Stussy.

After what seemed like a 20-year absence, he launched his label S/Double a while back with what he called the modern equivalent of a flea market stall—a small website featuring clean military and workwear-inspired clothes: T-shirts, caps, chinos, work shirts, and surf boards. The boards were both innovative and retro, hand shaped pieces that were grabbing the attention of a new generation of surfer. Despite all his achievements, his reputation and clout, it was if he’d pressed reset and decided to start from year zero all over again.

I wanted to catch up with him and find out about the ideas behind the brand and what motivated him to come out of what can best be described as early retirement.

On the flight over to New York from London, I had some doubts, or rather some conflicting thoughts let’s say. I realized that I was also curious about the past—about his namesake brand and his sudden departure from it all those years ago. I realized that the explanation for his resignation had never really rung true for me—like some kind of unsolved mystery. Maybe that was a question too far however—surely he’d be totally bored of being asked that by now. Who knows, it may even jeopardise the whole interview. Should I hold back, or should I give in to my curiosity?

I wanted to separate the man from the myth. I wanted to figure out, even if only for myself, what it was that meant this guy, despite his absence from the scene, still managed to cast his influence over what amounted to three generations of youth culture. And what was it that makes some of the most sussed people I’ve ever met regard him as the most switched-on of them all? At one point, years ago, it struck me that if so many of the people I look up to look up to him, then I’d really like to know who he looks up to.

In short, when we met for breakfast that morning, I was loaded with questions, like a tightly coiled spring at the end of a trigger. Drink your coffee, Jules. Be cool. Take your time, I told myself.

We met in the neat but compact dining rooms of the hotel Shawn’s staying at for the weekend. It’s one of those new boutique hotels—not many rooms, not overly priced, and with a beautifully disposed if rather eclectic interior. Velvet cushioned sofas, wood-paneled walls, gilt framed paintings, mirrors—everywhere. It’s the kind of place New York has been getting good at over the past few years now that it’s no longer edgy.

Shawn, it turns out, is friends with the owner. “Is Shaun here?” he says to the girl behind the reception desk after we’ve eaten.

“Shaun? The owner? No, he only comes in occasionally really.”

“Oh, okay. Well, can you give him a message? Can you tell him Shawn Stussy said hi? That’s Shawn spelt the correct way: S-H-A-W-N.”

“Sorry, Shawn who?” she says.

“Stussy. Here let me write it down for you,” he says graciously.

“You know Shaun?” she asks, as Stussy writes his name on a pad.

“Yeah, we’re old buddies. We go way back.”

“Oh,” she says, looking at him with a kind of quizzical expression that says she doesn’t fully believe him, not totally anyway. “Okay. I’ll make sure he gets it.”

I say to Shawn later, “I think she was maybe thinking if you two are friends, how come your room isn’t comp’d.”

“Oh, I’d never ask him for that and besides, I prefer to pay my own way, you know? Asking him to hit me up like that wouldn’t be cool.”

“I see, yeah. You’re right,” I say—not fully believing myself.

We step outside. It’s a sunny Saturday afternoon in SoHo. After this morning’s rain everything has a sheen and a freshness usually reserved for Hollywood movies and rarely seen gracing Manhattan’s gritty concrete and glass landscape.

By this point, we’ve spent a few hours together but even with that, I’m suddenly finding it hard to fathom the simple fact that I’m walking through the city with Shawn Stussy. Here’s the guy who set up one of the most influential clothing companies ever and then decided to walk off into the sunset—so far away, in fact, that he wasn’t seen again for a decade. He left the company and with it his own name, his own signature and handwriting—never (or so everyone thought) to be seen again. It’s kind of surreal.

As we join a mass of people waiting to cross the street, what’s running through my mind is that this guy’s legacy isn’t just a company that still bears his name—it’s infinitely more than that. It’s streetwear, it’s modern street culture, and it’s all around us. It’s informed the people who put this magazine together, it’s informed you too and probably everyone you’ve grown up with. Even people who have never heard of the brand or those who consider it wack have been affected by this guy’s legacy. It was a status symbol for movie stars as much as it was for rebellious, acne-ridden skaters. And here he is now walking through Manhattan in total anonymity.

The lights change and as we step off the sidewalk we both spot a kid wearing a black T-shirt crossing from the other side. He’s wearing skinny black jeans and oversized work boots. It would be just the kind of look you’d see paraded in a Rick Owens show if it were not for the fact that the T-shirt he’s wearing is Stussy. “The eight ball; one of my designs,” Shawn says. Before we get to the end of the block we see another kid, this time a skater wearing a Stussy signature T-shirt—again in white on black. And then we see yet another, this time the Stussy Rolex-inspired crown, all graphics originally drawn by Shawn decades back.

“It must be weird,” I say, “not just seeing your work but your own name and signature being worn by kids who have no clue who you are.”

“I don’t mind it. I’m okay with it now. I guess it means that the foundation I left there was good. But why haven’t they had a couple of new groups, new eras since then?”

“It’s a almost like a process of repeating the same designs—the same assets—on rotation again and again….”

“Right. Because as a design guy I’m just here thinking it could be a lot of things right now, you know?” he says.

At one point I ask him, “Do you ever get that Steve Jobs feeling? Like, do you ever imagine that one day you’ll get a call and it’s the brand saying, ‘Hey Shawn, we want you to come back to work’?”

“[Laughs] No. I’d never go back,” he says immediately, as if the suggestion wasn’t even worth a second’s thought.

Back in 1996, the word was he left the company he’d founded some 16 years earlier in order to spend more time with his family. It’s the kind of line we’re used to hearing from disgraced politicians or actors who can’t get any work. To the outside world, Stussy’s departure wasn’t only out of the blue, it made no sense at all. For a start, just a few years prior to relinquishing the company’s helm to business partner Frank Sinatra Jnr. (no relation), he had launched the brand’s first retail store in SoHo—104 Prince Street—just a few blocks away from where we’re now walking, in fact. Back then SoHo was a rent-frozen, rather shabby habitat to a long succession of artists and fellow outsiders. It was a "go-through" rather than "go-to" bohemian neighbourhood, its grand but rundown buildings successfully concealing their potential as high priced, des-res apartments. The Stussy store put SoHo on the streetwear map and it suddenly became a major destination not just for the store’s diverse but unashamedly hip customer base, but also for other streetwear labels, too. Sure, before Shawn left the company profits had been showing signs decline, but there were indications of major growth in emerging markets—especially Europe and Japan that would eventually counterbalance that local dip.

“I flew in yesterday and had dinner with James [Jebbia] last night,” says Shawn over breakfast earlier. James was the flagship store’s original manager. He also co-owned the Union store which had opened its doors just a year before in 1989 initially selling Brit brands like The Duffer of St. George and Burro and then eventually Stussy. All this, of course, was before James launched Supreme in ’94. Like X-Large, ALife, BAPE, Goodenough, Wtaps, Triple Five Soul, Silas, and pretty much any other streetwear label you care to throw into the pot, Supreme was built on many of the principles originally established by Stussy. But it’s James who seems to occupy the void left by Shawn’s departure as the scene’s main figurehead. Sitting there, listening to Shawn describe the previous evening, I wonder to myself if James’ enigmatic persona and recluse-like, "no interviews" policy wasn’t inspired by the veil of mystery that continues to surround Shawn due to his own media disappearance.

“It’s always great meeting up with James,” Shawn says. “And I got caught up on a lot of the guys, especially what’s happening in London, you know with Michael [Kopelman].”

“I know Michael really well,” I say.

“You do? Yeah, Michael’s a sweetheart.”

Based in London, Kopelman runs Gimme 5, the distribution company responsible for introducing brands like A Bathing Ape, Visvim, Neighborhood, Norse Projects, and beyond to the wider world. But the twister, the turning point, was when he began distributing Stussy.

“I wanted to see Michael before I came out here,” I say, “but I didn’t get the chance.”

“Oh yeah?”

“Yeah. Last time I saw him in fact I was doing an interview with Goldie. Know Wave UK was broadcast out of Michael’s showroom and I did a show with Goldie about Metalheadz.”

“Right, right.”

“It was a really fun interview,” I tell him. “I told Goldie how intense he used to be back in the day and he just laughed. Afterwards, he picked out some stuff from the new Stussy collection. It’s great that he still pulls Stussy product—I guess being one of the early International Stussy Tribe members.”

“When I was at Stussy, Goldie had the best collection of stuff. He had every hat I ever did. I know he prided himself on that. That was around 15 years ago—I don’t even know what goes on at Stussy anymore. I wonder who’s there—there must be somebody who knows who to send the stuff to.”

“In Goldie’s case, I guess it’s down to Michael.”

“Oh, of course—Michael. Michael would feed it out to people. Because I don’t even think anybody else there now would know who those people were. But Michael makes total sense. I’m glad Michael’s still involved,” he says.

The International Stussy Tribe was one of Shawn’s innovations. Not dissimilar to what brands like Nike now call seeding, it was a sophisticated form of product placement. In fact, it’s hard to tell if it started out as a huge act of generosity or as a moment of marketing genius.

“My thing was to try to do something nice,” he explains. “I made some jackets—just a few, a limited number of them. I sent Michael one and a few to the New York guys. Then the next time, I sent one to Mick Jones. Each one was personalized. And it went on from there. There were a few years of that happening.”

Imagine. At one end there’s Shawn standing in some kind of embroidery shop handing over to the guy a list of names and a bunch of brand new varsity jackets. At some point, his list includes Goldie, Hiroshi Fujiwara, Dante Ross, Paul Mittleman and Albee Ragusa, Barnsley, Jules Gayton, Alex "Baby" Turnball and brother Johnny, James Lebon and his brother Mark, Mick Jones, Don Letts over in London, and Luca Benini in Milan. And of course Lono Brazil, Keith Haring, and let’s not forget Nigo.

And then at the other end there are these guys receiving their box of goodies—T-shirts, caps and sweatshirts, and the most coveted gift of all, a varsity jacket with their name inscribed on the chest. Here Shawn creates and solidifies his very own global village, a virtual family born way before the mobile phone, the internet, and social media had come into our lives.

But, despite how it might appear from a contemporary perspective, it wasn’t a clique or a formal group. Sure, many of the guys knew each other—but in a loose and disjointed way.

Legend would have it, Shawn had met Hiroshi at the small coastal surf shop outside Tokyo where he was commissioned to make surfboards in the early 80s. Hiroshi went there to check out the outdoor skate ramp and clocked Shawn’s T-shirt. He’d met another skate kid, Paul Mittleman, and his pal, Al B, on his travels to New York, doing trade shows by way of introducing his brand to the world. Hiroshi is then hanging out at World's End on the King’s Road with Barnsley, buying Seditionaries and Westwood gear. Michael Kopelman and his crew would visit New York looking for sneakers and whatnot, and that’s when they met Mittleman and his crew. In turn, it was Mittleman who introduced the Turnballs to Shawn’s label in New York—and so it went.

“It was a real disparate group that connected on a number of levels,” he says. “It was really innocent, like a very truthful gathering. And it just felt right. It wasn’t a commercial thing.”

Looking at it today, when this kind of strategy is common to the point of being standard if not overplayed, it’s difficult to understand that the IST could have been born out of an altruistic gesture. Later on, even Shawn tries to frame it within a kind of strategic context, referring back to the very early days of the brand when his primary business was making surfboards.

“I was the guy who never gave anything away to surfers, because I knew through past experience with them—send them some stuff and you’re this month’s thing, and then as soon as the same kid gets a box from the next company you’re last month’s thing. I didn’t want to play that game.” And so, he says, he devised the International Stussy Tribe instead.

Even with that, there’s a kind of purity about Shawn, a kind of hippie-esque quality that’s instantly engaging. I can understand why he managed to command the respect of so many people—how he managed to galvanize the loyalty and support of such a variety of individuals for such a long time. Often, he’ll use words like innocent, in a way that has nothing to do with morality or religion—not directly anyhow.

It’s only when he says that as a kid his first job—at around 15—was making boards for a notorious and now legendary hippie commune that I get a better sense of what he means by the word.

“I was like the guy in Goodfellas. The kid who Joe Pesci shoots. Serving the drinks. I’m shaping the boards, and here’s six guys talking about drugs and the police right in front of me—but I never listened. As far as they were concerned, I was Switzerland. ‘He’s innocent, he’s a good hard-working kid.’ They didn’t pull me into the conversation. They knew I wasn’t a threat.”

He’s talking about the Brotherhood of Eternal Love. Known as surfer smugglers, they began as a small group of guys all of whom grew up together in the otherwise quiet and conservative suburbs of Orange County. John Griggs would become their leader—a high school jock turned rebel who, like his pals, drank too much, took heroine, and became a low level, if not occasionally rather desperate criminal. One day these guys go up to Hollywood and at gunpoint steal some LSD. It’s legal at that time—1965—a fact they are not themselves aware of.

Dropping LSD for the first time turns their world upside down. It’s like a Copernican Revolution. Committed to the transformative powers of LSD, they swear never to use firearms or violence again.

Many of them had started surfing in the early 60s, so they set up a kind of commune, first in Laguna Beach and then some of them moved further inland to Palm Springs with their wives and kids. Although Shawn ends up working for them making surfboards—learning, perfecting his craft—their main source of income is what goes inside the surfboards and what they can smuggle into the US from abroad.

“They were the first guys who were going to Afghanistan—buying a van, filling it up with you-know-what, and driving back. So it was a real innocent pirate era of surf exploration, slash whatever that became.”

This is just after the Haight-Ashbury Summer of Love has ended and now Laguna Beach has become hippie central with the Brotherhood of Eternal Love at the heart of it. “You could say these guys were the first wave of travellers—world travellers,” Shawn explains. But it was not only because of their booming drug trade. Many left the country for places like Canada or much further afield, as a way to avoid being drafted into the Vietnam War—something that also threatened Shawn along with his contemporaries like an overhead guillotine on a timer.

“I started surfing when I was in sixth grade and hung out with guys older that me—five, six years older. These guys all had to deal with the draft. So from 12-years-old, I had friends who were getting sent to Vietnam.” Like something out of a sci-fi movie, you became eligible for the draft when you reached 18. The draft board would then randomly select guys to enroll into the military by a lottery. Your name was picked at the same time as a number. Your name was assigned that number—1 to 365—based on the days of the year. Then it was just a question of time before your number came up and you were called in, trained, and shipped out.

“I get to high school and they picked my number. I was 185—right in the middle. But just then, the draft was abolished. It was like the weight of 20 people was lifted off my shoulders. Fuck, my life can begin. It was the first year you could let your hair grow—no hair code in school, so you could have a moustache and hair over your ears. If you look at my yearbook everyone has a ton of hair, and the guys who could grow moustaches had them too. But the year before, it looked like 1950s America. It was a perfect alignment. I graduated mid-semester in January. I went to the Army Surplus store, bought a backpack, sewed an American flag patch on it, and bought a rail pass and a hostel card. And then I went to Europe.”

***

Back from Europe, Shawn becomes immersed in the glam rock scene—as far from a GI crew cut as you could get.

“I’m with two surf buddies driving to LA to go to Rodney Bingenheimer’s club to see the New York Dolls. We’re wearing high-waisted bell-bottoms and platform shoes. We’re sneaking away from the beach with Rod Stewart haircuts to go see the Dolls. I’m still into Bowie, The Stooges, and MC5. And then, not long after that, I’m bonding with this new sound coming to the US called reggae and pretty soon the punk explosion happens and then that evolves into new wave. Me, I’m a big Talking Heads fan and The Clash—they’re the ones for me,” he says.

By virtue of his own curiosity and openness, he finds himself right there—always at the start of things, the cutting edge of it from the emergence of a Californian surf community onwards, to the acid movement, to glam rock, punk and new wave—taking it all in.

It’s no wonder that when he launches Stussy, it soon evolves from its initial surfer-orientated appeal to a much broader, inclusive church. Maybe you learn to suspend any petty prejudice or judgment when you’ve grown up under the shadow of a life-or-death lottery and have been schooled by yoga-practicing, LSD-dropping, hippie gangster surfers in search of peace and love. There’s that, but it’s impossible to underplay the impact of the draft.

“Sure, Vietnam plays a huge role for me. You could meet someone two years younger than me and not have anything like the same conversation at all. You have a kind of heightened awareness of your own freedom. But for a year or so, your life could have been very different.”

It’s new wave’s vibrancy and energy that inspires the surfboards and it’s Tony Alva’s original black and white script T-shirt that inspires the first Stussy T-shirt. Adopting and adapting. Refining and redefining. That’s the skill he applied to all his designs—from the boards to the T-shirts, to the chinos and baseball caps. A master of postmodern appropriation—whether it be the Chanel logo, the Rolex logo, a song lyric or a saying, he managed to disengage it from its original meaning and invest it with something more innocent, more inclusive, and more irreverent.

It’s an ability that was fuelled by travel. Like a cultural magpie, he went from place to place sampling whatever captured his imagination. “I would travel, spend three weeks in Paris, and then go to London. We’d be hanging out at Mark Lebon’s house. These are people I respect and we’re all on the same page. So there was this hip, artistic, bohemian thing going on,” he explains.

But it wasn’t all take, take, take. The strength of his idea—or perhaps his character—was also to contribute, to advance youth culture and create, in his own humble way, a new kind of community. Today, of course, it’s easy to travel without moving, but back then if you wanted to know something or see something new, there was no virtual option. That’s something that all the original IST members understood as the 1991 Tokyo gathering testifies. Along with all the other Tribe members was the late James Lebon. London-based James was also a member of Ray Petri’s Buffalo collective, and established Cuts—now known as We Are Cuts—which remains among the coolest barbers around. Possibly the first of the UK members to meet Shawn, he also filmed many of the Stussy gatherings and events. What’s evident from this footage is that under the Stussy umbrella, not only did these guys have an excuse to meet and hang out; it also gave them permission to play and have fun. They were young men, but it’s as if somewhere along the line they’d made a conscious choice that it was cool to be irreverent. And in some way it’s that sensibility which empowers them.

Initially, when things started taking off and he began hiring staff, this camaraderie and irreverence was also the kind of atmosphere he created back at Stussy HQ. “When it was 12-15 people, they were my people. We listened to reggae music really loud in the warehouse. It was a culture of like-minded people. My characters. They were all dysfunctional, fucking weirdos, but great weirdos. A great mess.” But he explains, as the company grew and he began to travel more and more, things back at base began to change. “The composition of the family that worked there changed. The group dynamic changed. It goes from 15-20 people to 50 people. Now all of a sudden, it’s populated with—who are these guys? I would come home from three weeks of traveling, it’s lunchtime, and I go, ‘What the fuck am I hearing on the radio?’ It’s the religious talk show and everyone’s sitting down having lunch.”

If the growing disconnection between Shawn and his own company was increasingly evident to him at warehouse level, the gap was also becoming apparent further up the management ladder.

“About the same time, all of a sudden the first A.P.C. shop opens, and by now Yohji Yamamoto and Commes des Garçons have evolved. Sure, I’m a surf guy and make shorts and corny T-shirts, but I just saw a different makeup of what Stussy could become. I would come back to Laguna Beach, and in a week I would find myself arguing with my crew of people about this new vision. Their response was like, ‘No, we do this.’ There was no feeling of unity or shared direction. There’d be a lot of that. I come home totally excited and jacked up, and after a few days my sails would be completely deflated. And then it was kind of like me looking around going, wow, this thing works the way it is. It works because Frank runs it.”

We’re sitting here in the restaurant’s dining room. It’s now emptied out and the staff is busy clearing and resetting tables, stocking the bar and generally fooling around. And me—I’m trying hard not to be distracted by anything. After all, this is about to be the moment when I hear the answer to the question that’s been bugging me for almost 20 years. Just then I feel a weird sense of guilt. Is this gossip or is it more than that? Did I turn up here to find out about S /Double and the man so many of us are indebted to on so many levels, or did I travel all this way to sniff out the truth behind why Shawn actually left his own business empire? Just then I realize he has had that effect on me too; there’s a disarming sincerity about him that makes you question and confront your own.

“A lot of years—complete immersion. Totally passionate about it. Living it. All the decisions were made by me, good or bad. I lived and died by them. There were no group decisions, there was no marketing, no merchandising. And it all worked for years, for everybody involved. Then there’s a change in the marketplace, a lull in the economy, or whatever it was. Wanting Stussy to be even bigger for some reason, they saw the growth as poor. And then there started to be people with opinions. And these opinions, from my point of view, were weak and driven by finances. You know what I mean?”

Perhaps, I wonder to myself, Shawn found himself witnessing his own company’s loss of innocence.

“They want to sell more next season and more the next season and I’m saying, ‘No, dude, we’re just doing this, it’s fine, we’re all good right now.’ At the same time,” he continues, “my girlfriend gets pregnant with Penn, my first son. The company had had three or four good years and I’d put all the money I’d made away. I was the exact opposite of the go-go, fuck the mortgage payments guy; I didn’t buy anything 'til I could pay for it. I had a nice wad that I’d squirreled away by design, but I wasn’t attached to it and I wasn’t going to be run down by the system. So it was kind of that perfect storm. I wanted to be as good as a father as I’d been at my business. I was 41 when I had my first kid and my other friends have got 18-year-olds and they’re like, ‘Dude, I worked through my kid's whole life.’ There was a little opposition to my decision to leave. People were like, ‘You don’t know what you're doing,’ and I was thinking, really? I’m not going to be 60-years-old with a bag of cut and sew over my shoulder in downtown LA at six o’clock on Friday night getting them made up for the delivery date. I’m a dreamer, you know, and the dream, well, there was another dream happening.”

So the rumors, the reports were ultimately true; he left because he wanted to spend time with his family—the direct correlation of which being that the Stussy Company had ceased to be a part of his family. It’s as if ever since he was liberated from the draft and Vietnam, he’d ridden the wave of his youth and innocence up to that point—a period which allowed him to go on a myriad of otherwise unimaginable adventures and to build an epic company. And then one day he returns from an adventure and realizes that he’s no longer the big brother, but just another guy who works there. Which obviously was not the case.

His radio silence and his subsequent role as media recluse therefore was no more than a by-product of his real life choice.

“So, when people say that you’re back, the way you look at it is that you’ve never been away?” I ask him.

“No, I’ve never been away. Never. But to the world it looked like I did, because there wasn’t enough output there to be noticed. But that’s a fair assumption to the world. I see that as easy, you know?”

“Except when it came to Stussy, of course.”

“Yeah, with Stussy—I disappeared. By design, you know? I just moonwalked out of Stussy.”

I ask about the brand that reignited my curiosity about Shawn and kicked off this whole trip in the first place. “How does it feel to be back in the world of fashion?”

“It’s okay. It’s fine. I’m just doing the little Japanese project. It’s a Japanese partner, designed by me in California, and then delivered to Japan. And they make it, under my direction and approval and sell it in Japan only. So it’s a real small thing. And it’s fun to do. I’m enjoying it and it’s getting a little love which is great.”

“Are you designing for yourself? I get the feeling these are clothes you’d like to wear, or rather that’s how it appears to me,” I say.

“I’m okay with that, yeah. That’s all I ever did before. I made it for me and I’m still making it for me. And yeah, I’m old and I like simple. Everybody makes simple stuff because as soon as it’s too new, it’s trendy and a little corny. It’s going to be hard to set the world on fire right now—so many people are doing the same thing and doing it really well and with much more wherewithal and finances. You know what I mean?”

“Are you trying to make a perfect Oxford shirt?” I ask him.

“An Oxford shirt is an Oxford shirt, but it’s the spirit that’s there. I’m way down here just having fun. It’s very different from when I started Stussy. The well you can pull from is only so big. So it’s a weird pot right now. But I had the easy days. It was easy for me. It was like a Wild West, uncharted territory. I just made Oxford shirts with a little crest on them, and that was some fresh thing. Think of that. That was 30 years ago,” he says.

It’s hard not to get sucked into that Manhattan afternoon rush. People are navigating their way around us as we stop to say our good-byes. Before I go, I ask him about his reputation and his legacy, about how he feels people view him around the world.

“I don’t even think about it. I have no idea about my reputation. I’ve pretty much been in the country for 15 years—in Santa Barbara and in Hawaii. And when I come here to New York, I see my friends and they’re just friends, like James. You know, I don’t even care, really. I can’t change it, whatever they think,” he says in an upbeat way.

In an instant I know that he is the same, pioneering free spirit everyone talked about.

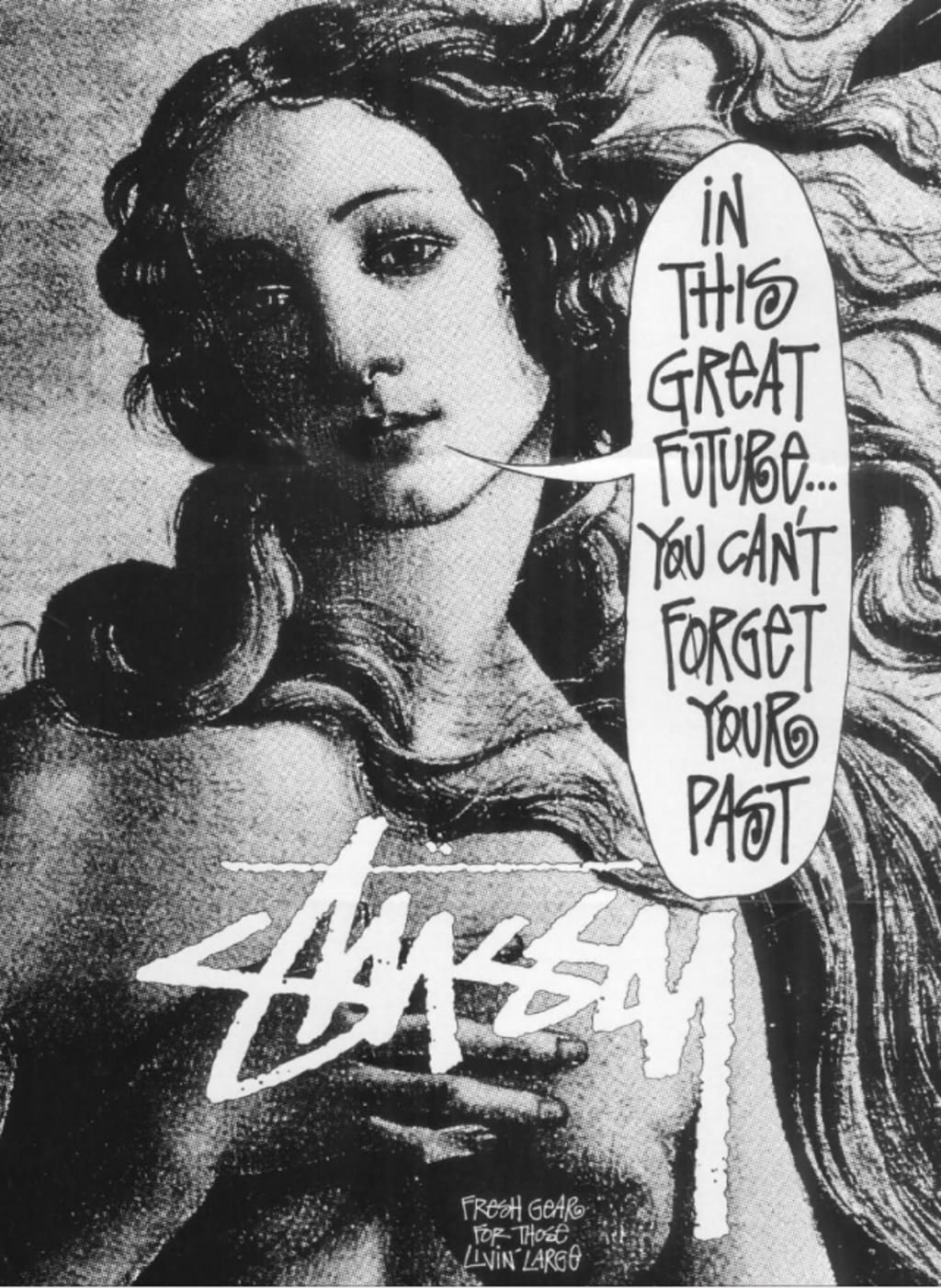

I remember one of the famed Stussy print ads featuring a quote from Bob Marley’s "No Woman No Cry"—“In This Great Future You Can’t Forget Your Past.” As we say goodbye, I come away with the sense that even though his past is one of the most important chapters in streetwear history, and he’s no doubt reminded of it every day, as far as Shawn Stussy is concerned, the adventure is far from over.

Jason Jules

About the Creator

Jason J

I love writing about people and clothes

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.