Lace — So Lovely, There Was a Law Against It

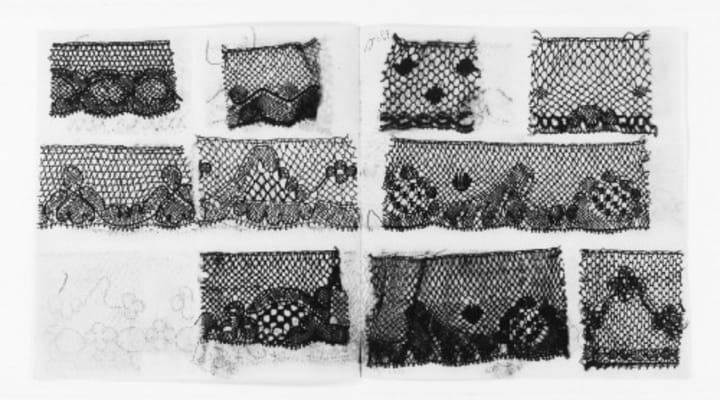

Tucked in Alexander Hamilton’s papers are snippets of black silk lace

Lace is all about what’s left out, a collection of holes formed into a pattern. The word evokes wedding veils, christening gowns, negligees, and fancy words like Alencon, Valenciennes, Chantilly, and Torchon.

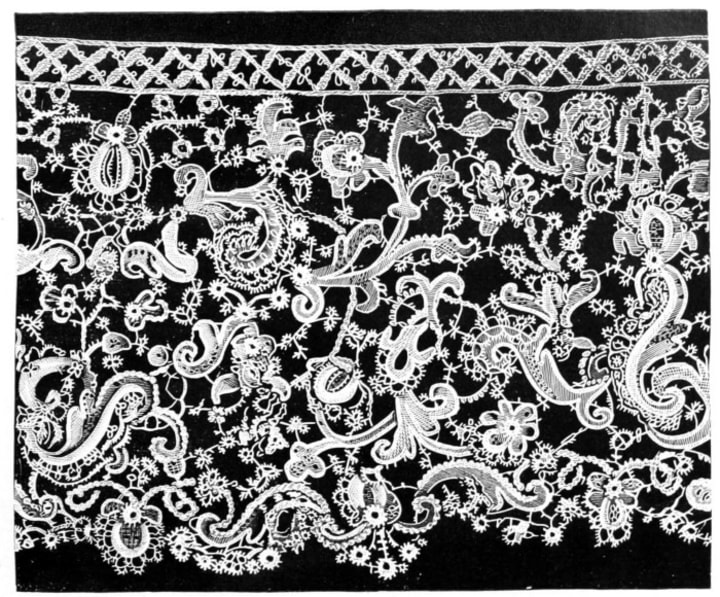

Most needlefolk eventually try their hand at making a piece of lace. We knit a diaphanous scarf or tat a hanky edge. Pretty as they are, though, it is the classic handmade bobbin and needle laces which take my breath away. Needle lace, created with a threaded needle and a pattern, takes the buttonhole stitch far beyond the world of buttons. On the other hand, bobbin lace shows us the endless possibilities of twisted, crossed, and braided threads. Bobbin lace also uses a pattern, usually attached to a small pillow. Straight pins peg the work as it unfolds from thread spooled on multiple dangling bobbins. The two techniques can be combined. These laces, rooted in Europe, may be floral or geometric or pictorial, silk or cotton or linen or metal. They always aim to add beauty.

I wondered if anyone still made such lace and if it were for sale. I have my oval box with bits of antique lace. For years I toted around a nineteenth century lace collar with scalloped edges and roses. I had bought it at the Montreal flea market by Champs de Mars — never quite sure what to do with it but loving it with all my heart. I wondered if I could add fine lace specialness to my sewing projects. Could I buy new handmade fancy lace? Or was I limited to fragments of antique and vintage trim? Or machine-made replicas of them? Finding the answers to my questions made me love lace even more.

The origins of lace are hazy and carry a whiff of the forbidden. In a charming subtitled video from a 2013 French convention of lacemakers, Mme. Michelle Andreu placed the origins of lace in the creation of braid trim. Others place it in embellishments of priests’ vestments. Initially vestments were trimmed with cut-work or pulled thread designs. Eventually, a minimalist innovated. They stopped cutting fabric to bits or pulling out threads for faggoting. Rather than remove components, the innovators built up designs by placing, twisting, and knotting threads into a pattern. Lace was born.

Thumbprints left by the legal system let us know lace was alive in Italy by the mid-1400s. Heavy duties were placed on it. Regulations, known as sumptuary laws, limited its use. Sumptuary laws address luxury items, “sumptuous” things. The Italian laws aimed to keep people sorted out by class and to tamp down excesses by ambitious non-nobles. Not everyone could wear silk. Pearls could not be worn by prostitutes in Venice, but only prostitutes could wear flat shoes or slippers in public. The use of cloth of gold and silver, woven from the precious metals, was restricted. To circumvent this, clever fashionistas had their sleeves lined with the metallic cloth and slashed to reveal the glinting cloth. Lawmakers responded by outlawing slashed clothing.

Lacemakers reacted to the restrictions. To maintain their meagre profits, they began using cheaper materials. Silk thread was swapped out for linen. Other lacemakers fled the country and carried the lacemaking tradition to northwest Europe. Wars, religious persecutions, and trade routes eventually transported lacemaking around the world. Missionaries would take it to Africa and Sri Lanka (where it is still made by hand).

Sumptuary laws also cue us into the origins of American handmade lace. In 1639 the town of Ipswich, Massachusetts passed a law forbidding anyone to buy or sell or wear or use lace. The law failed miserably. At times, Ipswich lace was bartered in place of currency. Martha Washington wore it. In full flower by the American Revolution, Ipswich lace is the only known American handmade bobbin lace.

Among Alexander Hamilton’s papers are samples of white linen and black silk Ipswich bobbin lace. In 1789, Hamilton, as Secretary of the Treasury, was tasked with taking a census of manufacturing. His minions discovered about six hundred Ipswich women and girls who made 41,979 yards of lace annually. The value of the lace was estimated to be worth nearly two thousand pounds sterling. (The American dollar was not yet adopted as currency.) Hamilton failed to share his samples with the President.

The use of lace to decorate clothing not typically seen by the public, “unmentionables” and so forth, may lie, in these periods when lace itself was forbidden. Certainly it led to robust smuggling efforts. Corpses in coffins were replaced with lace and carried across borders. Miscreants stuffed loaves of bread with lace. They wrapped dogs in lace and overlaid the textile with a hide.

No matter how quick the lacemaker’s hands, lace grows slowly. Watch this Belgian woman’s hands fly as she makes bobbin lace in a three minute video.

The labor requirements lead to high cost and relegates lacemaking to the poor or to those with time on their hands. In 1765, a single yard of Valenciennes lace for sleeve ruffles required a lacemaker to work 15-hour days for a full year. A pair of ruffles required four yards. The woman who made the lace would earn one-quarter of the cost of a pair of sleeve ruffles for a year’s work. Lacemakers were, according to some accounts, preferentially incarcerated and their lace sold to benefit the jails.

Lacemaking evolved into a cottage industry performed predominantly by women. Children as young as five were taught the craft in lacemaking schools and orphanages. It is sedentary job and time consuming. Lacemakers are often depicted gathered together outdoors or in a cottage. To entertain themselves, they certainly talked but others sang and had plenty of time to do so. Scholars have documented lacemaker songs with as many as four hundred lines.

In the early 1900s, missionaries taught Native Americans in California, Minnesota, New Mexico, and Wisconsin to make lace. Samples can be seen at the Oneida Nation museum in Wisconsin. But, by then, the cottage industry was already dead or dying. Men no longer wore lace to proclaim their wealth. Though Queen Victoria’s white wedding dress trimmed in lace set a tradition in 1840, machine lace could be substituted for her Honitan bobbin lace. Machine lace was much less expensive and gave the same look and feel to clothing and household goods.

Making handmade lace is now the purview of hobbyists and researchers. Finding it for sale is daunting and, when found, the price is prohibitive. Jules Kliot, Director of the Lacis Museum of Lace and Textiles in Berkeley, California shared that Alencon lace is still being made in France. He also noted some lace sold in European tourist venues is imported from Asia. Travelers to Sri Lanka can still buy locally made lace. Online shops feature narrow bobbin lace edging from American lacemakers and larger pieces from Russia. Lace may be found at trade shows or fairs in Europe.

But the days of buying handmade new lace by the yard are gone for most of us. You can buy machine-made lace or comb through the relic pieces of antique lace at estate sales and shops.

Of course, you can always try your hand at making your own. Lace museums in the U.S. and Europe offer online and in-person classes in lacemaking. Brussels, Belgium and Venice, Italy have lace museums as well as Detroit and Sunnyvale, California. Instructive videos and books also can help you get started.

Jules Kliot recommends the International Organization of Lace, Inc. as a good starting point for learning more about lace. The non-profit, dedicated to the study and preservation of all types of lace, has chapters in twenty-four countries.

Lace has captured eyes for over six hundred years. To my mind, it is the best use of negative space I know.

I consider lace to be one of the prettiest imitations ever made of the fantasy of nature; lace always evokes for me those incomparable designs which the branches and leaves of trees embroider across the sky, and I do not think that any invention of the human spirit could have a more graceful or precise origin.

Coco Chanel

About the Creator

Diane Helentjaris

Diane Helentjaris uncovers the overlooked. Her latest book Diaspora is a poetry chapbook of the aftermath of immigration. www.dianehelentjaris.com

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.