My life was always pretty average. I grew up in a small town in NJ where my father was a police officer and my mother a stay at home mom. I basically was a tomboy for a majority of my younger years; opting to hang out with my brother and play hockey instead of going to the mall and having girl time with my friends. My brother Timothy was my Irish twin; his birthday almost exactly 12 months to the day before mine. Growing up, he got bullied a lot and I vividly remember always trying to protect him despite being a girl and also being younger than him. When Tim entered high school, he experienced a rapid growth spurt, reaching the height of 6’7” by the time he graduated, but hadn’t grown horizontally which led him to still occasionally get picked on for being so skinny.

Tim always had dreams of being a United States Marine. He enlisted in the Corps before graduating and left that fall of 2001 for Boot Camp at Parris Island. This would have been my first time away from my best friend and I wasn’t prepared for that. I demanded sleeping bags be set up on the downstairs floor of my parent’s house so that I could be sure to say my goodbye when his recruiter showed up in the middle of the night to retrieve him. I wrapped my arms around Tim’s leg as he dragged me across the floor with his recruiter quietly saying, “He will be back in 13 weeks” which, to me, sounded like a life time. Reluctantly, I let his leg go and off he went to become the man he always wanted to be. We were able to keep in touch via postal mail and the occasional phone call. During his training, New York would experience the worst terrorist attack in history when two planes crashed into the Twin Towers. Little did I know that a war would ensue and Tim would be fighting in it.

After Tim graduated boot camp, he went on to continue his MOS training as a Machine Gunner and later shipping off for his first deployment to the second battle of Fallujah in Iraq. He returned from war like most men and women had; suffering from severe PTSD. It was something I had never seen first hand and to say my heart was broken watching him go through the struggle is an understatement. Still, Tim pushed on and finished his four years in the Corps. When he got out, he knew he wasn’t done with his military career and he knew he wanted to accomplish even more. This is when he decided to join the National Guard and endured the brutal and arduous SFQC. The drop out rate is 80 percent but Tim was not one of them. He graduated the course in 2011 to become an elite soldier: a Green Beret… Tim’s most rewarding and glorious moment. He continued with his passion for firearms and became a Weapons Sergeant in A/2/19.

In 2012, Tim volunteered to deploy to Afghanistan during OEF. His job was to train Afghan commandos how to use their weapons to protect themselves in the event of an insurgent attack. With two 19th group guys and a young support guy on the range one day in September 2013, the exact person Tim was protecting the commandos from infiltrated their range and gunned down our guys. SSG Timothy McGill, SFC Liam Nevins, and SGT Joshua Strickland succumbed to their wounds on September 21, 2013.

Time stood still for a moment as I tried to comprehend what the notification officer was telling me. I remember watching my father fall to his knees and scream in pain from his heart as it shattered into pieces. I couldn’t quite cry, I couldn’t quite move, the only thing I could do was go out on my back deck and scream Tim’s name in the hopes that he would come running out back and this was all a dream. Unfortunately, it was a reality and it was one I had to face. As the days went on, I found that I couldn’t ingest any solid foods. The only thing I could stomach was alcohol because it numbed my pain. I lost 13 lbs in the next few weeks. I hated myself, I hated the agony and the void in my soul, and most importantly, I hated the person who took my brother’s life. Two days after receiving word of Tim’s passing, we were shuffled down to Dover, DE for the dignified transfer. Mostly a blur, I do remember wondering why we were roped off on the tarmac. Why couldn’t I personally receive my brother’s casket home? When the back of the plane opened, I saw not three caskets but three flag draped boxes carrying three separate heroes coming home to their final resting place. As I forced my body not to kick the rope down and run down the tarmac, they lifted my brother’s remains into a truck and drove off. The overwhelming feeling of abandonment and desertion overtook me.

After Dover, we brought Tim’s body back to his hometown where, unbeknownst to us, there was a huge homecoming in the small town of Ramsey where well over a thousand people lined the streets bearing American Flags and signs thanking Tim for his sacrifice. It was bittersweet. Firefighters, police, military, friends, family, complete strangers all came together as one to mourn the loss of one man.

After Tim’s funeral I began suffering from what I like to call as my version of “sympathy pains.” Night after night I would fall into a deep sleep where I would be under attack or I would watch Tim get severely injured. I’d wake up in a pool of sweat and my heart racing; on occasion I’d wake up screaming. I began logging the dreams as they progressively got worse and eventually rolled over into my everyday life. I began to watch my brother die in my imagination every single day. I wondered if he knew he was going to die. I wondered if he felt anything. I imagined and struggled with wondering if he died immediately or suffered on that foreign ground with no family around to kiss his head goodnight. Instead, his head bore a single gunshot wound. My mind began to punish me with torturous thoughts and scenarios. I sought help and laid out my demons and explored ways to destroy them.

As time and therapy went on, I began to lose faith in my once devout Catholic life. I began to blame God for taking my best friend. The guilt of betraying my Eucharistic Minister father set in and I went to my Priest. He asked me what I would do when I was at my lowest point and most angry at God. I replied, “I usually sit in my car with the music blasting and scream at Him how much I hate Him.” My Priest then said to me, “If you’re cursing him out, you’re still acknowledging he’s there which means you never lost your faith.” Those words set the precedent for a lot of future grief episodes. Most importantly, when my father was suddenly rushed to the emergency room nine months after Tim’s death. What was assumed to be a stroke turned out to be much worse and cruel than we ever could have imagined.

After many tedious and sometimes painful tests, the doctors diagnosed my father with Creutzfeld Jakob Disease (CJD), a rare and incurable brain disease which attacks only 300 people a year. I felt my world crumble again as I watched my father slur his words and look around confused and lost while his head was wrapped with hundreds of wires. The blast of agony was back in my soul and the remaining pieces of my heart were suddenly shards scattered around my empty body. We brought my father home to where we knew it was only a matter of time before he would cease to exist. As days went on, we continued to watch him rapidly deteriorate. A man so insanely intelligent and so well preserved physically was dying right before our eyes. We tried to give him the best few days to weeks as we could, not knowing when his time would come as CJD is not very predictive when it comes to a timeline. In addition to his slurring and confused state, he quickly began to lose his motor skills, had frequent minor seizures, and began to go blind. Hospice soon became the norm in our home. Towards the end of his life, he began hallucinating, he would see demons and angels, he would see Saint Peter, and would ask me to pray with him before he fell asleep. I disposed of all my anger towards God and granted every last wish to my ailing father. Just four weeks after being diagnosed, my father suffered a major seizure which forced him into a coma and he quietly passed two days later.

The dynamic of Tim’s death and my father’s death is ironic and insignificant at the same time. They both died of head “wounds” but I felt I could have saved one while the other’s demise was irreparable. The loss of my brother accelerated my father’s death and I firmly believe that despite his diagnosis, he died of a broken heart.

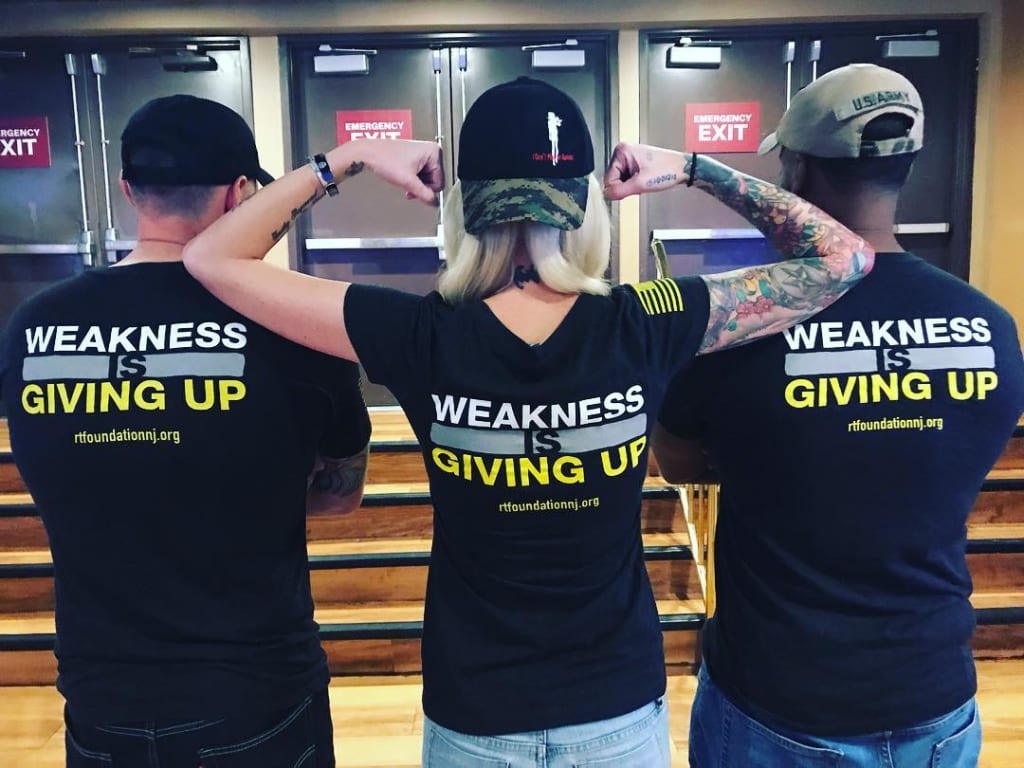

It was at this point that I knew I needed to continue my path of philanthropy and complete my foundation which I had drawn up plans for the months after Tim’s death and leading up to my father’s. I pushed my fears and grief aside and relentlessly worked on my non profit goals. In the interim, I moved my life south and out of New Jersey where all the tragedy lay. I became Peer Mentor certified with TAPs, I encompassed the SF community and joined the Steel Mags, and I took the legacies of two men who inspired and molded me and told their stories in the hopes of spreading not only awareness of the depth of this war and the impact of rare diseases, but to continue to push open the door of strength and healing to those enduring the same mourning. I’ve gone through some let downs and some set backs in the meantime which may have hindered me but never stopped me. RT Foundation was created as the gift of paying it forward; as a way to acknowledge that fate isn’t qualified to be shifted or molded to your appeal. The memories that pop into my head on the regular about my father and my brother are the strengths they portrayed and the motivation they exuded. They weren’t afraid to die but they were afraid to leave us behind. So the best thing we can do as a whole is to fight that fear and assure their spirits that we can push forward for them.

To all who have passed, to all who have made the ultimate sacrifice, and to all who are left behind to pick up the pieces: one piece at a time will connect the fracture of death and one memory a day will keep them here.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.