I’ll never forget when I saw my English professor cry. He had just read “When I have Fears That I May Cease to Be” out loud and was overcome by John Keats’ poetic potential lost to an early death. I was a junior in college, and my classmates felt awkward to say the least. Many stifled giggles and sideways glances were exchanged. After all, there stood an older man at the front of the room, weeping over words.

But in that awkwardness, I fell in love with Romantic poetry. By being so moved in front of a group of millennial twenty-somethings, he gave me permission to do something that we usually don’t: he gave me permission to care.

I relished our poetry unit and continued on with multiple electives. My senior year, I decided to dedicate my final thesis to Percy Bysshe Shelley, the most underrated of the Romantics in my opinion. I was fascinated by the seeming contradiction of Shelley’s life and work: at 19, he published a pamphlet titled “The Necessity of Atheism,” which earned him expulsion from Oxford but then at 24, he wrote “Mont Blanc,” which was teeming with devotion.

Many critics read the latter poem as a 180-degree transition to religiosity. But as a brazen college student -- not unlike Shelley -- I didn’t agree. To me, Shelley hadn’t suddenly converted to Christianity; instead, he had found faith through a willing suspension of disbelief.

His first pamphlet was agnosticism. He knew that we couldn’t know God, and he was frustrated by 19th-century England’s vehement ignorance of that. Five years later, “Mont Blanc” was a discovery of faith in the French Alps. By standing at the base of the great apex and looking up, Shelley describes a feeling of awe that was importantly not zeal. The magnitude of the mountain is indescribable, so he ascribed it the label of “Power.” The capital P makes it other-worldly, almost God-like, which encourages the most common reading by literary critics.

But halfway through the poem, he transitions to lowercase: "Mont Blanc yet gleams on high: — the power is there, / The still and solemn power of many sights, /And many sounds, and much of life and death."

The transition from P to p is more than grammatical randomness. To me, Shelley moves from externalizing Power to internalizing power. He realizes that Mont Blanc is only awesome if he is in awe. In that way, faith requires believers, transferring the power to the person.

In the summer of 2016, I followed Shelley’s footsteps from 200 years prior when he wrote Mont Blanc in 1816. I embarked on a Romantic adventure, looking for power of my own.

And to be sure, Mont Blanc was powerful. I felt small next to something so large. In many ways, I felt more than small — I felt trivial. I was still recovering from a devastating break-up and beginning the difficult process of applying to medical school. I didn’t feel powerful.

But on that trip, as I traveled around Europe alone for 3 weeks, the solitude provoked strength. Loneliness leaked away and was replaced by liberation.

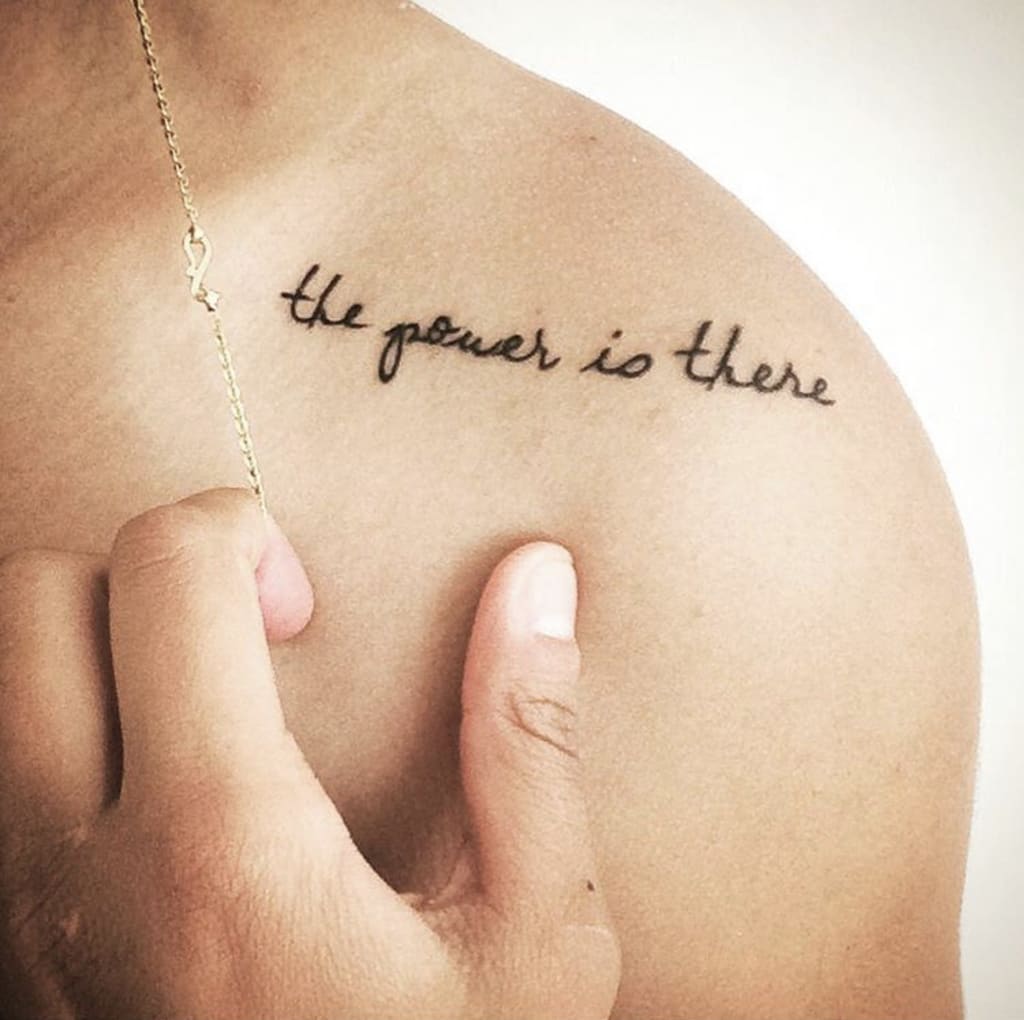

I was 22 and looking out at the rest of my life — and for the first time, I wasn’t scared. Reveling in the feeling of being young, wild, and free, I had my newfound Shelleyan power inked onto me while abroad. And I brought it home as a reminder — a reminder not only of that summer but also of the start.

Now, the power is there -- permanently.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.