Afterimage

An unexpected windfall helps a writer rediscover something he has lost.

I don’t remember how the war began, but I remember how it ended. Some of the memories, I’m sure, are just photographs really, brought to life by the strength and strangeness of time: the sepia-toned ticker tape, the grinning grenadiers, the forelocked sailors in their polished shoes. Among these, only one I know to be completely authentic. It’s of my mother, reading a telegram in the kitchen one morning, in the soft light of the curtains.

I had never met my father, but I knew he was abroad, seconded to the Pacific for the final weeks of the war. His plane was a few hours from London when it crashed into the jade of the Indian Ocean, full of tired young men and thoughts of home. My mother went up to her room when she finished that telegram, and didn’t come out for days. He had been something she waited for, something like hope.

I grew up in the grey fifties, when the world was a museum. Home was a museum too; we kept his clothes crumpled in the drawers, his knapsack stuffed, his notebooks serried, his trophies high and dusted on the shelf. Long jump, triple jump, hurdles: we lived in fear of knocking them off. One long summer, we came in and the shelves were bare. She’d had enough, she said. All of them, sold.

I stayed indoors after that, to keep an eye on her. I began to read, and sat up late in the lamplight; on my thirteenth birthday, I received a pair of shining, tortoiseshell spectacles, then cried when made to wear them. An eye for detail, my mother soothed. I could still count the veins on a leaf, even if I couldn’t see the tree.

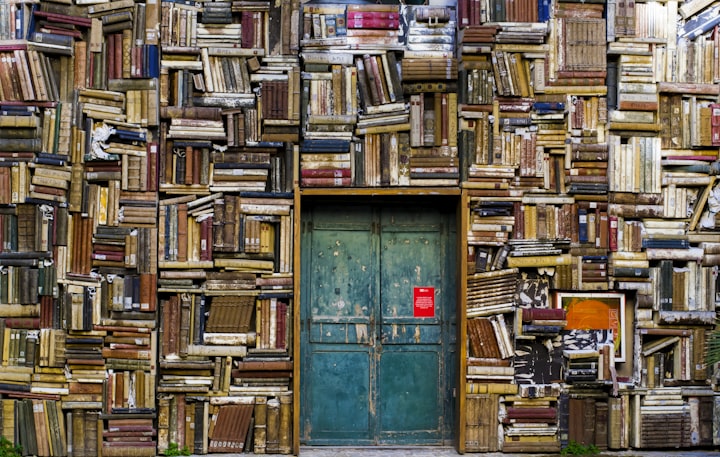

Life began in the sixties, for me and for everyone else. I had a mind for books, if not for the rigours of study, and eventually saved up for a flat in Paddington to ply my trade. In those days, you could pick up a book on the street in Notting Hill and take it in your pocket to a dealer in Soho; they’d buy it for twice the price, and by the time the shutters rattled down at five pm, the same book would be gleaming from a glass cabinet in Kensington or the King’s Road. You could get by, just about, flitting across the city with your jacket full of books.

I got to know money: I learned, for instance, that a book bought for a sixpence at nine o’clock could fetch a crown by teatime; I knew that first printings held their value, that third printings dropped like stones. I knew the way the leather curled around the trusses of a first-edition Lewis Carroll, and I knew the scumbled glue of a fake. I even got to know the grand old bookshops in Piccadilly, where you could buy a book from stacks on the ground floor, ride the elevator skywards – oh those whispering cages, with men in suits to pull the levers! – and sell it on the top floor for twice as much.

I read every book I bought, then sold them on. I read gold-leafed bibles and Torahs that had been kissed through prayer shawls; I read Freud on fathers and Vico on the cycles of history. I read Borges (then just becoming popular) – the infinite library, where no book could ever be found; the Book of Sand with its infinitesimal pages. Much of what I read I can no longer remember. All I can summon is the shape of the story, its truth.

In such a state of mind, it was no surprise that I should happen upon my own, mysterious book. Life has a way of striving towards fiction. It was August, the end of the long summer at the stub the decade – a summer with fine snows of poplar and ballets of flies. A summer that seemed as long as childhood itself. I was rooting through a set of crates outside a mint-green townhouse on the Portobello road, when I found a small, black notebook – leather bound, with soft rounded corners. A stand of elastic pulled it shut, tight as a bowstring.

I looked inside. It didn’t make sense at first: just strings of dates, co-ordinates, place names like Okinawa and Kyushu and Iwakuni. The owner threw it in for free with a dog-eared bootleg of the Thousand and One Nights. I thought so little of it, indeed, that I grew careless: a few days later, I deposited it in a jacket pocket, swooning over a folding chair in the Spitalfields Arcade, and went to pay a boy to shine my shoes. By the time I returned, my crate was half empty, and the jacket and book were gone.

Strange what a little absence can do. As long as I had it in my possession, the notebook had seemed impenetrable, cold and remote. But once it vanished, I became obsessed. I began to think of the notebooks on my father’s shelf – their rainbows of faded inks, the taut sinews of elastic that clamped them shut. A few months passed, and soon I was convinced that the little black notebook was a repository of great truths, casually squandered. The words were impenetrable to me, but to someone else they had been a delicate code, a few spatters of ink the form of an entire life.

Within a year, I had happened upon the fanciful notion that the little black notebook had belonged to someone in my father’s regiment or company – someone who had conducted the same training exercises, been on the same flights. Okinawa, Kyushu, Iwakuni. Perhaps it had even belonged to the man himself.

I turned over the city for that notebook. I combed Portobello Road, I leafed through Soho, I climbed from the silt of the Thames to the top of Primrose Hill. I rode the escalators in the gleaming department stores, zigzagging through the void. I carried on trading only to pay my way, to subsist. But this, too, became harder and harder: people grew wise to what we were doing, and the shop clerks looked down at us with horn-rimmed derision. I never had a family of my own; everything I did earn I spent on my niece – toys when she was young, then clothes, then flowers. By the turn of the century, everything could be looked up, accounted for, as if in an infinite library. Everything, it seemed, except the little black notebook.

I stopped work four years ago. My knees had come to grate from miles of walking; my hips had grown too light and muscle-less to cantilever a crate. I sit here by the lamplight, writing stories, trying to remember what I have read. My eyes are getting worse. I no longer know the price of a first-edition Lewis Carroll, or a tattered Thousand and One Nights; I can no longer identify a fake. What money means to me now is time – time to sit, to write, to think. I experience it as food and water, a roof between me and the London rain.

My niece comes over occasionally. She finds stacks of my papers, wipes off the coffee stains, straightens them out. Sometimes she’ll enter a short piece for a competition – something from the back of a magazine, perhaps. I’ve even won a couple: a fifty here, a couple of hundred there. A few more days under the lamp, a few more weeks. Last week she blustered in, scarf already unfurling itself in excitement, her face capillaried red from the cold. She had some news, she said. One of my stories had won a prize. Only this prize was worth rather more than the others. This prize was different.

I didn’t believe her when she told me how much. She said it again. It’ll keep you going for at least a year, she said. A whole year. What would I do?

What will I do? I find myself returning to the little black notebook, again and again. My first instinct was to search for it. I could hire taxis to comb Portobello Road, the second-hand stores of Soho, to ferry me up Primrose Hill. I could spend every day on those escalators, zigzagging through the void. But I’ve decided not to. I’ve decided, instead to keep writing. I write now with that little black notebook in mind, in the hope of capturing, if not the full story, then the shape of it, its truth.

About the Creator

Thomas Peermohamed Lambert

I am a freelance writer and journalist based in London.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.