Why Girlboss Feminists Make Us Nauseous

The girlboss shatters the glass ceiling, only to turn around and rebuild it under herself

Not long ago, fitness influencer Grace Beverley (formerly known under the moniker GraceFitUk) released her highly anticipated debut book entitled Working Hard, Hardly Working: How to achieve more, stress less and feel fulfilled. The book claims to give insight into the productivity hacks and management strategies that launched Grace into the forefront of entrepreneurial success.

She is an Oxford graduate, the CEO of two successful companies, and Forbes recently featured her on its ‘30 under 30’ list. The ultimate girlboss, perfectly poised to give this type of advice. However, following its release on April 15th, 2021, readers’ reception of the book left a lot to be desired. It presently has a 3.6/5.0 rating on Amazon, and the reviews are not great.

“Another girl boss book about how to work hard yet the author comes from a multi-millionaire family.”— Kelly

“Only relevant for people given millions of pounds by their parents. Limited value for anyone else” — AP

“I think the author forgets to acknowledge her privilege. Middle class millionaire family background, Oxford university graduate — aspects which the average girl cannot relate to. A plan B in essence. There are others worth looking up (particularly WoC) to with much more helpful ‘self help’ books.” — Shannon

“Not impressed — written by someone from a privileged background who doesn’t acknowledge that her rich family, upbringing, and luck of her Instagram popularity is what’s led to the success of her businesses. Not a fan of the waffly writing style either.” — Abi

The reaction to Grace’s book underscores the broader skepticism that the Girlboss caricature in pop culture has encountered in recent years. Previously a celebrated figure embodying ideas of women’s empowerment and hard work, the girlboss is now subject to public outcry, widespread criticism and overall disdain. This article aims to answer two central questions. What the hell is a Girlboss? And why, in God’s name, do they make us sick to the stomach? I argue that girlboss culture is an extension of white feminism that privileges individual success while claiming its results are universally applicable. It is blind to the exclusivity and familial luck necessary to secure a spot in the girlboss club. As the political culture has grown more conscious of socio-spatial issues (race, ethnicity, sexuality, class etc.), it has fallen out of favour.

The advent of the girlboss figure

The most famous version of the girlboss came in 2014 with the release of Nasty Gal founder Sophia Amoruso’s memoir entitled #Girlboss.

The book chronicles the life of the former CEO and details how she went from a university dropout, working menial jobs for health insurance to forming a multi-million dollar company that started on eBay. If you hate reading, you’re in luck because Netflix turned the book into a series of the same name starring Britt Robertson. It had a one-season run.

From then on, the girlboss became a figure synonymous with entrepreneurial grit and corporate innovation. She is a fearless woman that occupies space at the top of the traditionally male-dominated corporate hierarchy. She sets her own schedules and is her own boss, as well as the boss of many others. When Amoruso wrote this memoir, many lauded her success and personal drive in creating a name for herself. But the public admiration for Amoruso and the girlboss culture that she inadvertently popularized would soon turn sour.

Girlboss culture and white feminism

Before diving any deeper into this topic, let’s be clear about one thing. The term ‘white feminism’ is not an attack against all feminists that happen to be white. It has a precise definition in academia and is simply one of many strands of feminist theory. The feminist umbrella is wide and includes theoretical frameworks such as liberal, radical, post-structural and decolonial feminism, among others. Therefore, it is possible to exist as a white person and not embody the core tenets of white feminism.

White feminism dates back to the first wave of feminist agitation in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. During this period, suffragists fought for the right to vote and the increased political participation of women across different societal levels. The notion of white feminism emerged as a critique and descriptor for members of the suffrage movement who were accused of centring only the voices of caucasian women while downplaying the significant contributions of other groups of women to the movement’s success.

These feminists labelled white male supremacy and patriarchy as the central problem plaguing all women and advocated for equal rights. In doing so, they ignored other intersecting factors such as race, class, ability and sexuality that condition women's experiences everywhere. By positioning all women as equal victims of patriarchy’s negative externalities and ignoring its differential impacts on minority women, these feminists failed “to hold white women accountable for the production and reproduction of white supremacy”(Moon & Holling, 2020, p. 253–254). White feminists were uninterested in dismantling the system of racial oppression and white supremacy. They cared more about how it affected their lived experiences personally and wanted a seat at the table. A bigger slice of the proverbial white supremacy pie, as it were.

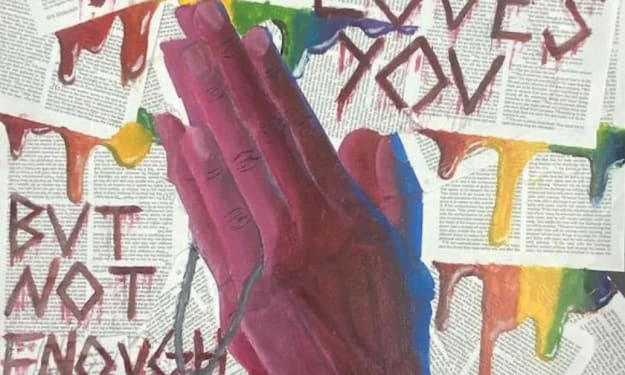

How does this relate to girlboss culture? Girlboss culture is a liberal repackaging of the ideas at the heart of white feminism. It privileges the voices of white, wealthy women, rallying for their increased participation in the (white) male-dominated corporate environment while disregarding the barriers to entry faced by women of colour. The girlboss lays claim to feminist messaging while advocating for individual rather than collective success. Dunne (2020) notes that this form of feminism, absent a political core, is hollow and meaningless and “invalidates and delegitimizes crucial feminist work through its disregard for intersectionality and political change” (p. 267). The girlboss shatters the glass ceiling, only to turn around and rebuild it under herself.

The myth of the self-made girlboss

The girlboss narrative hinges on the idea of the ‘self-made’ woman. I think self-made is a silly word. Your parents got hot and heavy, and you were the result, so, on a technical level, no one is ‘self-made.’ Its more popular definition, revolving around the accumulation of wealth and success through your own hard work, is also problematic. How do we quantify hard work? Where do we draw the line between self-made and not self-made? Forbes previously called girlboss Kylie Jenner self-made, and the world lost its God damn mind. Clearly, there is some variable, namely familial wealth, that precludes someone from consideration as self-made.

Let’s return to the earlier example of Grace Beverley. Many of the complaints in the reviews of Grace’s book question her gall at giving advice on success and emphasizing her self-made status when she comes from a wealthy family. Her mom is a senior curator at a famous museum, and her dad is the head of a consultancy firm. Her grandfather was knighted (by the Queen of England!) and was the founder of the now-defunct Trafalgar House, a multimillion-dollar company that, during its heyday, was the most successful property development conglomerate in Britain. Grace has attended posh French-speaking nurseries, top schools and, despite her upbringing, maintains that everything she built was through her own efforts.

I don’t know who needs to hear this, but you don’t have to be self-made. If your parents have their own Wikipedia page (unless they’re infamous serial killers), you’re probably not, and that’s okay. It is okay to admit that other people’s efforts account for at least part of who you are. We are all continuously made and unmade by contributing factors outside of our control. The neighbourhood in which we live. Who our parents are. The schools we attend. Wealthy children can no more control the accident of their birth than poor children, and we shouldn’t blame them for it.

That said, people will cast blame if you lie about your experiences. This is the crux of the myth of the self-made girlboss. The majority of girlbosses are not ‘self-made,’ yet they operate and proselytize like they are. And it pisses people off. I have realized that rich people have a tough time conceptualizing just how wealthy they are and how materially different this makes their lives from other people. The image forwarded by girlboss culture is that of a battle-worn woman who had to scrape and claw her way up the corporate ladder while dodging a host of obstacles set up by “the man.” This image is a fallacy for most of the women who cling to the title of girlboss. The Kylie Jenners, the Grace Beverleys and the Rachel Hollises of the world started the game on third base and now deign to dish out advice to consumers who don’t even have a spot on the pitch. It is disingenuous and intellectually dishonest.

Covid-19 and the travelling businesswoman

The hype surrounding the girlboss died almost as quickly as it developed. Girlboss culture thrives on relatability and the idea that they are “just like us,” but this pandemic has proven that’s not even remotely true. Maybe it’s because most of us were in lockdown and had way more time on our hands to think critically and reflect, but the hypocrisy of the girlboss figure became apparent. And there’s nothing that the layfolk love more than watching hypocrites burn.

While we were self-isolating and masking up, our girlbosses were jetting off to Dubai, Greece or Mexico “for business,” flouting Covid-19 protocols and showing us exactly who they are. It’s hard to care about the lavish life of your favourite girlboss when you’re more worried about your nan who’s in hospital being treated for covid. There’s a standard that we, regular people, must follow that doesn’t apply to the girlboss figure. And we’re heartily sick of it. If they don’t care about the health and safety of everyone else, why should we give a crap about the books and products that they’re peddling?

From the ashes of the girlboss rises the intersectional feminist

The reputation of the quintessential ‘girlboss’ is dying. Or dead. The public now recognizes that it is an exclusive club filled with predominantly white women who had a leg up in life and now proceed to give us advice on how to be like them, completely bypassing the fact that they had a leg up in life. As girlboss feminism evolves, we are distinctly aware of the hypocrisy, falsehoods and privilege that bolster it. And it makes us nauseous.

The girlboss is untenable because she clings to a feminist agenda while dealing deadly blows to the movement’s progress. For this reason, we must continue to reject notions of girlboss feminism. It serves a select few women while neglecting the rest. An intersectional approach to feminist theory that acknowledges the diversity of experiences among different groups of women is the future of feminist advocacy. We are not all born into the same set of circumstances (economic or otherwise) and should stop acting like the corporate mechanisms that allow a select group of women to climb to the top of the ladder have universal applicability. Instead, we should continue to challenge this rhetoric and advocate for the deconstruction and rebuilding of these mechanisms to be more inclusive and free from bias.

---

References

Dunne, S.A. (2020). Lena Dunham’s apology to aurora: celebrity feminism, white privilege, and censoring victims in the #MeToo Era. Celebrity Studies, 11(2), 267-270. https://doi-org.proxy.library.carleton.ca/10.1080/19392397.2019.1623489

Moon, D.G. & Holling, M.A. (2020). "White Supremacy in Heels": (white) feminism, white supremacy and discursive violence. Communication and Critical/Cultural Studies, 17(2): 253-260. https://journals-scholarsportal-info.proxy.library.carleton.ca/details/14791420/v17i0002/253_sihfwsadv.xml

Schollenberger, K. (2021, Jan 27). Who are Grace Beverley's Parents? The Sun. https://www.the-sun.com/news/2217807/grace-beverley-instagram-fitness-star-gracefituk/

Staples, B. (2018, July 28). How the Suffrage Movement Betrayed Black Women. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/07/28/opinion/sunday/suffrage-movement-racism-black-women.html

---------------------------------------------------

Originally published on Medium

If you liked this post, please be sure to like this post! If you're able to leave a small tip, it'd be greatly appreciated and also, feel free to check out some of my latest stories. I recommend starting with this one:

About the Creator

Laquesha Bailey

22 years old literally, about 87 at heart. I write about self care, university life, money, music, books and whatever else that piques my interest.

@laqueshabailey

Enjoyed the story? Support the Creator.

Subscribe for free to receive all their stories in your feed. You could also pledge your support or give them a one-off tip, letting them know you appreciate their work.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.