The Threads of Women’s Lives

Author Linda Sittig’s passionate quest

As a child, author Linda Harris Sittig sometimes wore homemade clothing. Her friends in her northern New Jersey neighborhood also wore cotton dresses, corduroy pants, and pajamas sewn by their mothers. Although those other moms might have been excellent seamstresses, none could compete with Mrs. Harris’s tales of her grandfather’s Philadelphia fabric mill. They didn’t know which Irish towns wove the best linen. None rivaled the care she took to assure her daughter wore quality fabric.

Before purchasing a dress for Linda, Mrs. Harris ran her hand over the fabric to gauge its texture, turned it inside out to measure the seam allowances, and scrutinized the crispness of the pattern. She preferred to buy clothing from the sales section of a high-end shop than bargain clothes from a cheap one. Tellingly, Linda’s mother firmly steered Linda away from shoddy cloth and shoddy workmanship. Linda grew up “with a fine appreciation of fabric” yet wouldn’t learn the family backstory till decades later. The result would propel her Threads of Courage book series and her Strong Women in History blog.

New Cathedral Cemetery, a thirty-eight acre of green in northern Philadelphia, resonates with serenity and peace. In the years since opening in 1868, tall obelisks and statuary-topped pedestals have sprouted from the earth. Trees have fattened and grown lush. In 1993, Linda traveled to the cemetery to research her family history. A puzzle met her at the family vault. Her great-grandfather James Nolan, the mill owner, rested here in his designated space. Nearby lay a woman only identified as Mrs. James Nolan. Appalled that a person would be left immortalized as the appendage to another, with no hint of her own identity, Linda set sail on a journey of discovery. Who was this woman? What was her story?

Along the way, she learned why her mother warned her not to buy shoddy.

The woman buried as her husband’s wife was Ellen Canavan. Ellen, born in 1843 in Ireland, came from a family who knew their way around cloth. Her father was a weaver. Her mother was a sought-after seamstress. Her brother became a wool merchant in Philadelphia. Ellen dreamed of following the family trajectory and making her living in the textile industry as well. She courted James Nolan as a potential busines partner. He turned the tables, courting and winning her as his wife. Family oral history lays his success at her feet and this is where shoddy cloth comes on stage.

Originally, “shoddy” was a name for a specific wool cloth — a fabric made by recycling used wool fabric and, at times, leftover bits from the manufacturing process. The wool components were ground up, glued together, heated, and pressed into sheets of fabric. During the rush to outfit the soldiers fighting in the Civil War (and, according to critics, to increase profit margins) manufacturers used shoddy cloth. The wool was hot to wear. The fabric fell apart. Linda recounts the misery of Union soldiers, returning in the rain from the First Battle of Manassas (Bull Run). Weary, their vexation compounded as their shoddy cloth uniforms melted in the rain and dropped off into the mud.

Back in Philadelphia, Ellen came up with a solution — to combine cotton from Georgia with Pennsylvania wool and create a superior uniform fabric.

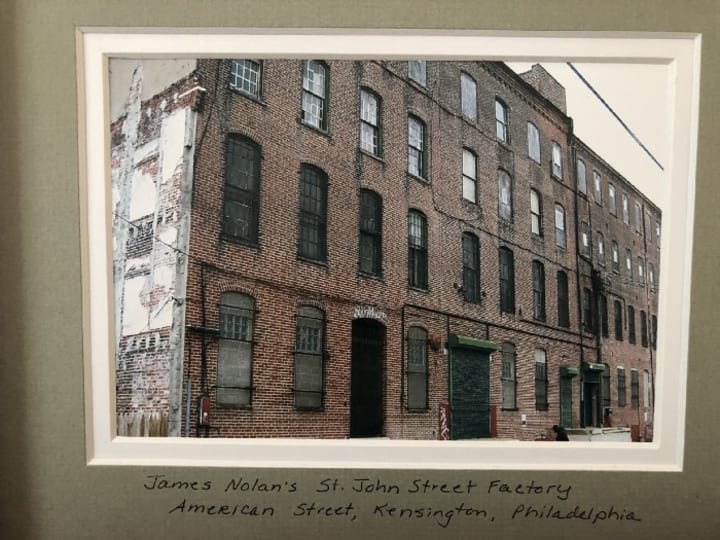

James Nolan began manufacturing this cloth at his mill in the Kensington neighborhood of Philadelphia. The durable, comfortable fabric became the cornerstone of his fortune.

“I found out about Ellen and how she never got credit. It really irritated me. The more I thought about it, it irritated me more and more. She deserved to have her story told.” Linda decided to champion the stories of Ellen and other women “shoved aside” by history.

From that springboard, Linda has never looked back.

Her first book in the Threads of Courage series, Cut From Strong Cloth, is set in the Civil War and based on Ellen Canavan’s life.

In her second book, Last Curtain Call, Linda follows members of the Canavan family to a life in a mining town in western Maryland. The title references the curtain rooms of company-owned mining towns, rooms which delineated the desperation of women and their children’s lives in the late 1800s.

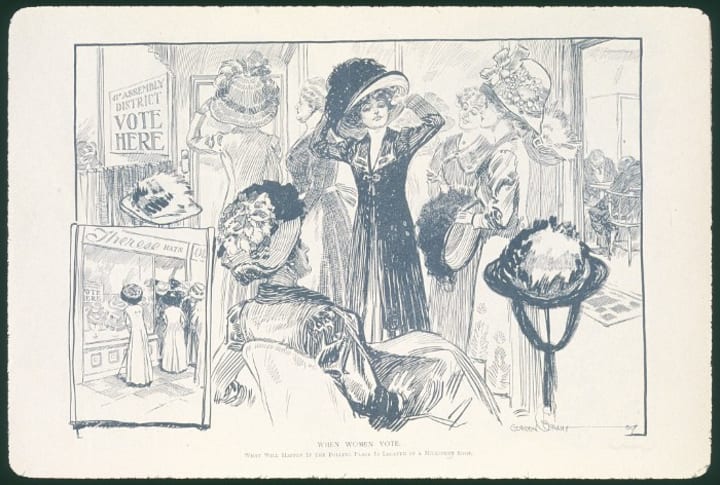

Carrying the thread onward, Counting Crows moves the Canavan story to Greenwich Village and the time to 1918. Young Maggie Canavan works in her aunt’s millinery shop and is touched by the influenza pandemic, women’s suffrage, and other upheavals of the time.

Coming soon is Opening Closed Doors, set in the 1950s. Virginia seamstress Josie Murray’s customer wanted Austrian shades — a fussy, flounced, and festooned version of Roman shades. Making Austrian shades requires grommets and drawstrings and the heart of an engineer. Josie knew the Purcellville public library carried a book with instructions for making an Austrian shade. There was a problem: as an African American, Josie could not borrow the book. What followed was pivotal to the desegregation of Virginia’s libraries.

Linda believes the intermingling of textiles and women’s stories is understandable. “They were a way for women to express their creative spirit in a time when they did not have the ability to work outside the home. Everyone could learn to sew. Sewing never was seen as frivolous.” Textiles and needlework became an avenue for more. “The need not to just clothe, to keep the house warm, but to be decorative as well.”

Since 2012, Linda’s blog Strong Women in History has celebrated the lives of women like Ellen Canavan. Each month she shines a light on a woman’s life, a woman who may have gone underrecognized and unacknowledged, yet deserves our attention.

Linda’s mission to tell these inspiring histories has “changed the way I navigate around the world…always looking for stories to pop out at me.” Seeking out hard facts and atmosphere for her writing, she travels to museums, libraries, tiny villages, and big cities. In Ireland, she looked for the towns where her mother promised “they made the best linen.” She has picked up a spindle to learn first-hand how to spin wool. The tricky lessons gave her “a different appreciation of fabric.” A woman of heart and hard work, she burst into tears when an archivist showed her the Sanford insurance schematic of the Nolan textile mill. Her mother’s oral history had been validated.

Subjects for her blog can fall into her lap. Friends send her emails. A docent in a French museum tipped her off to a woman of note. The name painted on the side of a Georgia ferryboat led her to Katie Hall Underwood, a midwife on Sapelo Island. Sapelo, a Georgia barrier island seven miles off the coast, is only accessible by plane or boat. It is the home of the last intact island-based Gullah community. From the 1920s to 1968, Katie Hall Underwood, a daughter of freed slaves, delivered over one thousand babies. Linda Sittig is determined to keep the contributions of women like Katie Hall Underwood alive.

About the Creator

Diane Helentjaris

Diane Helentjaris uncovers the overlooked. Her latest book Diaspora is a poetry chapbook of the aftermath of immigration. www.dianehelentjaris.com

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.