The Business of Feeling

A short guide to efficient songwriting

I am a loud and proud queer singer-songwriter from Melbourne, Australia. I go by the stagename "Mouk." and I am currently the happiest I have ever been. I took the chance to pursue my dreams and although I haven't "made it" yet, I am learning every day and loving having the opportunity to be involved in the songwriting community. I released my debut single in collaboration with artist and producer James Sully on the 27th of August 2020. The track got over 1,000 plays in the first day with no external promotion other than our artist social media sites. In this piece I want to share some of the tips and tricks I've learned along the way to create great and meaningful songs!

Overview

I have always been an emotional person. There have been many times where I have been told I feel things more strongly than the people around me. I have learned to communicate my thoughts and feelings thoroughly and this has partially been through the art of songwriting.

Communication and connection are at the center of songwriting. Effective songwriting allows a connection between the listener and the songwriter. As songwriting extraordinaire, Pat Pattison has said,

“We are in the business of feeling”

Pat Pattison, 2019

My approach to songwriting starts off with some hardcore self-therapy and then turns clinical when I begin to refine it into a finished piece. I understand how my listeners consume my music and what my fans are generally more receptive to. It's a process of give and take, you need to be listening to your audience as much as they are listening to you. What do your listeners need from you to stay interested and hear what you are trying to say?

An important thing to note is that you don’t need to know music theory or have a vast knowledge of songwriting techniques to be a great songwriter. Many artists are writing great music before they learn standard songwriting practice. However, knowing and applying different techniques will certainly bring confidence and ease to your songwriting.

I am predominantly an indie/ pop/rock artist. The information provided in this piece will be influenced by that but the techniques I write about can be useful and applicable to any genre of songwriting (albeit some more so than others).

Here are some things to consider when writing great music:

- Lyricism

- Internal vs External Language

- Metaphor

- Sense Writing

- Tension and Resolution

- Harmony

- Rhyme

- Rhythm

- Contrast and Repetition

- Structure

- Conviction

- Drafting and Patience

Lyricism

Not all music needs to have lyrics, however the clearest and easiest way to tell a story is with words. Personally, the lyrics are the foundation of my work. Everything around the lyrics, i.e harmonic arrangement (chords), rhythm, tempo, instrumentation, volume, all work as a bed to support my lyrics and present the story. I start with lyrics and work around them. Although this is not the only way to do things, this is what I know best and therefore lyricism may take a huge focus in this document.

Internal vs External Language

External language refers to the world around you, describing the physical parts of the situation, where it takes place and what you’re doing. Internal language is describing what you think and how you’re feeling. You can use your words to create imagery that can reflect your internal thoughts. Depending on the vibe of the song it can be heavier on one side or equally balanced.

Below is an excerpt from my original track, “Lemon, Lime & Bitters”. The bolded lines are external lyrics, used to set the scene and give context to the internal lyrics, written in italics, which are the internal thoughts and reflection that have come about as a result of the external situation.

“Waiting half an hour for you

Just to get a poor excuse

Oh the things you put me through

Always talking down to me

But talk is all you’ll ever be

Stuck in superiority

And tensions keeping us in place

Just waiting for my heart to break

With my next mistake”

A song made of all external lyrics would provide very little for the audience to personally connect to. It would be very objective and cold. A song with only internal lyrics would be more like a monologue, heavy and complex. Potentially quite pretentious and boring. Though different songs can benefit from using more of one type, it often works well to have a moderate balance of both internal and external writing.

Metaphor

Metaphor is a super powerful tool. Think about how often people use examples to make their point and how effective it can be. The psychology of tying new information to previous knowledge has been proven to strongly assist in retention and understanding. Simply put, metaphor is describing by comparing situations, saying this is this, and the mind meshes the two things together to understand the point that the songwriter is trying to make.

Very simple examples of this include “feeling blue” or having a “broken heart”. These things are not physically happening to people but we understand the meaning because of the imagery behind it. In my track “Red” I describe the emotional pain of a deteriorating relationship and desire to get revenge with the terms, “bloody knuckles”, “bleeding hearts” and “bleeding through my fingertips” to get some graphic and confrontational imagery into the listeners mind and intensify the message.

By using metaphor we can engage the other senses for the storytelling in our songwriting, solidifying the effect and feeling. Metaphor, by definition, must be false. otherwise you are just describing, rather than comparing and creating new imagery.

Sensory Writing

Most people describe situations visually but we can make it a lot more fun than that. You don’t have to rely on visual storytelling to bring the listener into your world. Think about all five senses: sight, smell, touch, taste and sound. If you’re new to this, try picking one object, person or situation and describe it with all five. Talk about how her eyes sparkle, the way her hair smells, the way your heart pumps when she touches you, the way she tastes when you kiss her and the sound of her laugh when you pull away. When using the senses you can combine it with the use of metaphor, “she had diamonds for eyes” or “honey on her lips”.

You don't necessarily have to use sense writing in a particularly direct way either. If I were to write “it was a cold winter's day” I could also write “the air was crisp, and my nose was dripping.” The combination of crisp air and a dripping nose implies that it was a cold day. Add in something about the sun shining above you and you’d also be indicating the time of day. Have a think about what information you can provide without saying it explicitly.

Tension and Resolution

Imagine you’re running on a treadmill at the gym. You’re making progress and seeing numbers but the run is monotonous and boring. Songwriting isn't about progress and numbers. Interesting songwriting is creative storytelling. It's about the journey of ups and downs and getting from point A to point B in a creative way. We want to be running on a path by the creek with hills and grass and beautiful scenery. Think about writing a song the way you would think about a book or a film, there is almost always a climax towards the end, a lesson to be learned, tension and resolution. To have a calm, resolved moment you must first have tension built up to get rid of. The downhill run is much sweeter after we’ve run to the top.

There's a range of ways that we can create tension in our songwriting. We can use questions or intense lyrics, create dissonance in our chords or melodies, have abundance or sparseness in our instrumentation, have space in our rhythm, an unusual beat, etc. if you create a standard and then stray from it, you’re creating tension. If you want your song to sound concluded, be sure to come back to the standard and resolve it at the end. There is always a powerful eeriness left in a song that is unresolved, but sometimes it doesn't pay off. Remember to listen to your heart and what the song needs with the message you are trying to convey.

Harmony

Sometimes music just feels right. Sometimes they don’t. Knowing a little bit of music theory can come in handy and help you understand why things feel the way they do. Music theory is super vast and complex. It's very difficult to wrap your head around but once you start to understand the basics, things get a whole lot easier. We’re just going to touch on the basics in this piece and try to make it nice and simple.

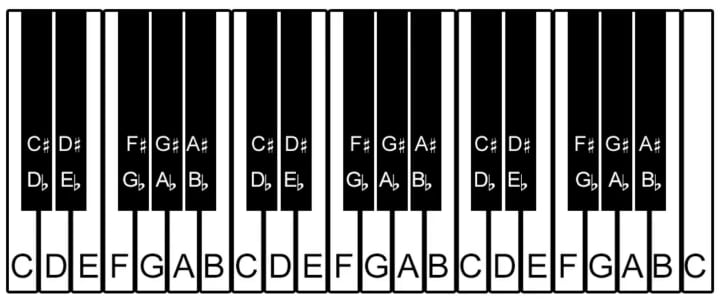

Below we have a diagram of a piano keyboard. We’re using this instrument because all of our notes and their relationships to each other are clearly laid out in front of us. In western music, we tend to group our notes into octaves. Despite the name, an octave consists of 12 notes. The white notes are simply named after the first seven letters of the alphabet, ABCDEFG. The black notes have two names depending on their relationship to the key/tonic note of your piece (we’ll get to that, don’t worry) and which note it is in reference to.

If we want to talk about the black key in between the C and D notes we can call it either C# (C sharp) or Db (D Flat) depending on the context. Starting from the “C” note and moving upwards (right and sharper or higher in pitch) we then have C#, but if we were talking about the note in relation to the “D” then we would be calling it a Db because of the flattening (going lower with) the “D” note.

Now that we can name all the notes, let's talk about keys, scales, and chords. If we want to play a song in the key of C major - the “easiest” key, we will end up using only the white notes on the keyboard. This is because of the pattern that we use to count up the notes in the scale. The pattern for a major scale is tone, tone, semitone, tone, tone, tone, semitone. Where a tone is a “whole step” or two movements across the keyboard (ie. C to D) and a semitone is a “half step” or one movement across the keyboard (ie. C to C#). So by using our major scale pattern, (TTSTTTS) we will end up with the notes C D E F G A B C as our C Major Scale!

Sidenote - the first C and the last C are the same note but in different octaves

If we wanted to have an A Major scale instead, we still use the same pattern but we end up with different notes. A B C# D E F# G# A. The pattern lands us on some of the black notes so we use them instead.

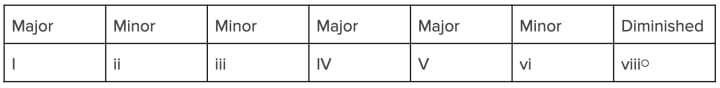

A chord is made from two or more notes played at the same time. Musicians use roman numerals to talk about the chords in relation to the key. In a Major key (not scale) the pattern for chords is:

So for our A major key, the chords we will have will be:

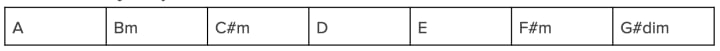

There is a bit of a hierarchy when it comes to the chords in a key. The A chord, our “I” or “one” chord, is known as the tonic or home chord. This is where the music sounds most stable. Tension and resolution can be created using chord progression. Whenever you want your piece to sound resolved, return to the tonic. When you want your piece to sound tense, stray from the tonic. In general the order from least to most dissonant sounding chords rank like this:

Most music can be written or played sufficiently with the use of a chord type that we call triads which use the 1st, 3rd and 5th note of the scale. The pattern that we can use to count up the notes for a major triad (sounds happy) is to start on the first note, count up four semitones for your next note and up three semitones for your note after that. If you wanted to play the same chord as a minor triad, (sounds sad) you would instead count up three semitones from the first note and then four semitones after that. This would keep your “1st” and “5th” notes the same, but would flatten your “3rd” making it a minor chord.

If I wanted to write a song in A major, my tonic chord would be the A major chord (shortened to just the “A” chord) consisting of the A, C# and E notes.

If I wanted to play the V (5th) chord, also a major, it could be the E, consisting of E, G# and C#.

If I wanted to play the ii (2nd) chord, a minor chord, it would be the Bm consisting of B, D and F#m. In a B major scale the D note would usually be a D# but because we are playing in the key of A where the D is a natural, the B’s third is “flattened” and the B chord becomes a Bm.

Sidenote - if you are playing these chords on a guitar which has six strings, the chord is still considered a triad. The three notes are being played but some are being doubled into different octaves.

This is just the tip of the iceberg when it comes to music theory. It’s important to apply what you are learning as you go and before you progress so it sticks in your head and you can avoid getting overwhelmed.

Rhyme

Not all lyrics have to rhyme, but the use of rhyme is a fun and effective way to catch a listener's attention and make a song memorable. There are two different kinds of rhyme types I want to talk about, perfect and imperfect rhymes.

Perfect rhymes have the same sound at the end. Rat, cat, and thermostat are all perfect rhymes with each other. So are through, blue and chew - they all end with an “oo” sound. The length of the word doesn't matter and neither does the spelling, as long as the vowel and consonant sound in the end is exactly the same. Perfect rhymes are boring when used all the time but very effective when used in contrast with less stable rhymes to create a real sense of resolution after the tension.

There are many different kinds of imperfect rhymes, these are the ones that make your lyrics interesting. They are taking your listener off the straightforward treadmill and onto the running path. This might be something that you have been working with subconsciously but it also might be a little difficult to wrap your head around so down worry if it takes you a little bit of time to be applying it consciously.

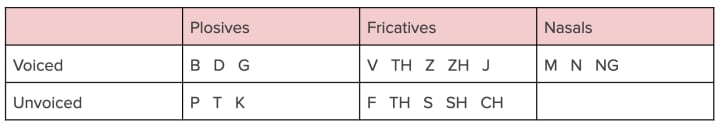

Some imperfect rhymes are stronger than others. It all comes down to how we match up the consonants. Something that is important to understand is the consonant families and how the consonants relate to each other. Check out this table:

The sounds in the top and bottom rows are the same, except for the ones on top you need to use your voice, and the ones on the bottom you don’t. Plosives expel air outwards, mostly using your lips, fricatives are consonants made mostly inside the mouth but with your lips open and nasals are consonants made with your mouth closed and come from your nose and throat. The best way to understand these is to do them out loud. So go ahead, try and make “D” or “duh” sound without using your voice. Interesting, hey?

Here we can see the different groups and how they might relate to each other when used in a song.

Family rhyme: same vowel sound + same consonant family

Eg. night/bride, myth/cliff, fame/mane

Additive/subtractive rhyme: same vowel sound + adding/subtracting a consonant

Eg. go/don’t, left/yet, range/day

Assonance rhyme: same vowel sound + different consonant family

Eg. night/shine, bit/ring, behave/make

The most important thing is to keep the vowel sound the same at the end.

Rhythm

Catchy hooks are often more about the rhythm than pitch. Of course an interesting use of notes can be cool and stick in your head but you can create a memorable line using only one note and some creative timing. Have a listen to Mr Brightside by The Killers. The melody for the most part doesn't jump around too much. It's all in the rhythm that makes it catchy.

Little bit more music theory for you. This gets a little complicated and difficult to explain over text so we’re just going to skim over it quickly until I can eventually make some educational songwriting videos. Music is split into bars and beats. Usually our radio music is written in a time signature called 4/4, pronounced “four four”, (and sometimes ¾ which sounds like a waltz). This means we can count four beats in a bar and then the loop resets.

Just like with harmony there is a hierarchy of stability and instability. The first beat of a bar is the most stable, then the third, then the second and forth. We call the first and third beats the “strong beats” and if you want to highlight something as important, it works really well to place it there. To place everything on the strong beats often becomes predictable and boring. It is nice to create interest by fitting some pieces in between and adding in some pizzazz! The further you stray from stability, the stronger your resolution will be when you return to it. Aim for unpredictability that still fits within the grid.

Contrast and Repetition

Understanding the idea of contrast made the BIGGEST improvement to my songwriting. This is tied in with the application of tension and resolution. Humans like familiarity. Annoyingly, they also like surprises (good, safe and comfortable surprises). If the same motif or section is repeated the whole way through a song it gets tiresome to listen to. If everything is constantly changing, the music becomes chaos that the listener can't keep up with. That’s why it's important to find a balance between the two. Establish a pattern (create your standard) by repeating something once or more, then create interest with contrast by introducing a new idea.

Applying contrast between sections literally saved one of my songs. in Lemon, Lime & Bitters, the melody in the verses and chorus is pretty much the same the whole way through the song. The only thing that was vastly different in both melody and harmony was the bridge but honestly there was nothing interesting enough to even keep listeners engaged long enough to get there. By adding a pre chorus that contrasted in melody and harmony between the verses and the chorus, I was able to cleanse the palette and refresh the listening experience enough to return to a familiar melody in the next section. This made the tune releasable again in my eyes.

Structure

Have a think about the different sections of a song and what their role is in the storytelling process. Each section has a purpose, be intentional with your songwriting.

The chorus holds the main idea of the story and reinforces it throughout the song. It is usually where the hook of the song sits.

The verses are the bulk of the information, you can put as much or as little as you want in the verses.

The bridge is your major opportunity to change things up a little bit, use it to show a different point of view, to change the mood, change the chords, change the key, etc

A pre chorus is usually used to add an extra kick before jumping into the chorus.

Instrumentals, intros and outros can be used to give space and contrast to the other sections. They can also be used to build up or cool off from other parts of the song.

A refrain is a line that is repeated, sometimes in place of a chorus or perhaps at the beginning or end of a verse. Refrain lines are often catchy or hooky.

You can structure a song whichever way you like. A common pop structure would be: verse, chorus, verse, chorus, bridge, double chorus. A typical folk song might consist only of verses. A garage rock song might only have a chorus and instrumental or a dance track may only have beats and a refrain line. The possibilities are endless and you get to choose how you want your song to sound!

You can also think about your structure within your sections. Think about which lyric is going to open and close your section with a bang?! How are you going to create tension at the end of your verse? How will you create resolve in your chorus? How will you build it back up after your chorus? Remember to take your listener on a journey, structure your song in a way that never gets boring!

Conviction

Arguably the most important part of songwriting is that it has to be believable. It has to evoke emotion but how can it do that if you don’t tell it with intention. As rock music extraordinaire, Dallas Frasca once told me “people can smell a rat”. If you don’t believe what you’re singing how can you expect the audience to? How are you going to connect with them? Why would they trust a liar? Make sure that your delivery holds authenticity.

Drafting and Patience

Don’t get me wrong, you can smash a song out in a short amount of time. However, I’ve found that my favourite and most polished tracks are the ones that I come back to and tweak over and over. I’m not saying to agonise over things, patience is a virtue but you’ll never get anywhere if you are just waiting for inspiration and not writing! Remember to “write without fear, edit without mercy” (Rogena Mitchell-Jones). Get anything and everything you think down on paper and then pick out your favourite parts and structure them into a song. If you get stuck, leave it for a while, work on something else and then come back with a refreshed mind. Whether you can feel it or not, you are always learning and soaking up the new ideas that you’re exposed to.

Here is my process when writing the song “Peachy”:

As a poor musician, I didn’t have much money to buy a gift when invited, last minute, to a friend's birthday party. I decided to write her a song. Little did I know, I wasn't going to be able to smash it all out in the short amount of time that I had. Here's all I got down before arriving at the party (I had a bit of a crush on this girl and it came out in my writing) :

Peachy

I’m feeling peachy keen

When she’s with me

My life feels a dream

And if I’m sleeping

Or just Imagining

Then she’s the greatest thing that I ever come up with

My "friend" was very flattered, and seemingly satisfied with just a chorus for the time being. Asking me to sing it to her a couple times. It might be important to mention that the word “peachy” is a reference to her hair at the time, dyed pink but faded to a cute peach colour.

The vibe I was going for was a crossway between our music tastes. Grungy/pop/rock, with energy similar to “Kiwi” by Harry Styles or “Cherry Bomb” by the Runaways. I planned for an instrumentation heavy track without too much heavy lyrical content.

I decided on a song structure:

Chorus

Post chorus

Verse

Chorus

Post

Verse

Chorus

Post

With the post chorus being:

Peachy Keen

Peachy Keen

Peachy Keen

She’s the greatest thing that I ever come up with

I considered making my previous chorus a verse and having the chorus just be:

Peachy

I'm feeling peachy

Peachy

Peachy keen

But even though the song is supposed to be lighthearted and upbeat, I felt that a chorus like that wasn't strong enough. It needed to be a little more than "I like you and I feel good" because what I was feeling was a little more complicated than that. So I went back to my old chorus.

At this point, my friend and I had started seeing each other more regularly and intimately. As we headed towards a relationship I was more determined to finish the track.

I started to plan the structure and rhyme scheme for the verses so they contrasted with the chorus. Using placeholder words I marked this down:

hello dee dee

hello dum

hello de de

da da da da dum

Repetition at the beginning of the lines with contrast on the last line to keep it interesting and an ABAB rhyme scheme within the section.

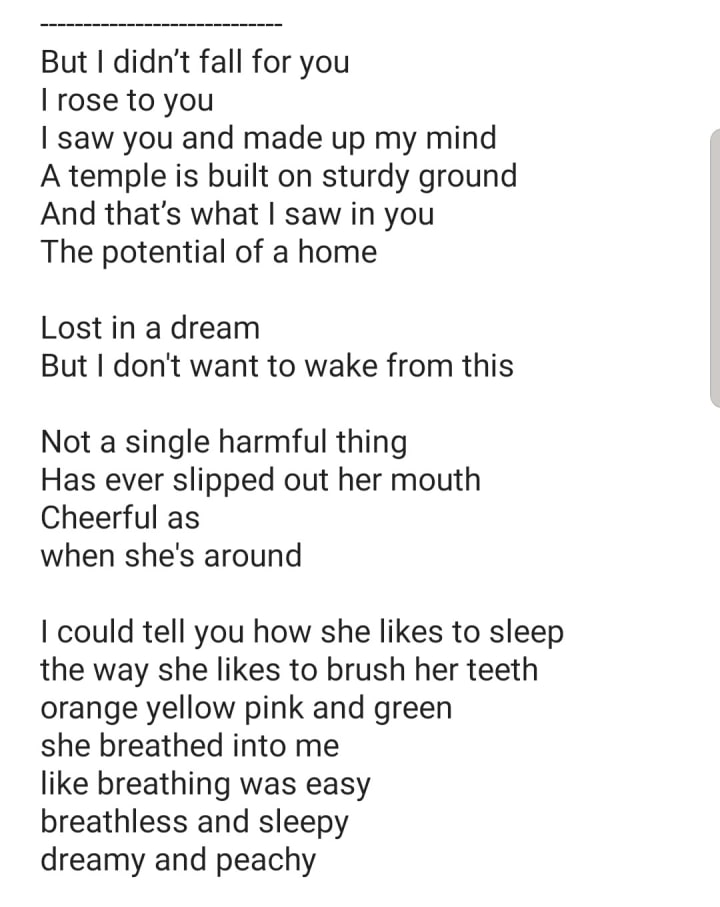

As we got closer and eventually into a relationship, I started noting down significant feelings or phrases that I thought of eg.

And I started to rearrange my thoughts to fit into my rhyme scheme.

As we started to drift apart, the vibes of the song changed and it felt like a disservice to keep the message of the track so lighthearted when it was more complex than that. I continued noting down significant thoughts, feelings and situations in my notes and pulled everything together. Here was my last draft of the lyrics and the structure:

[Chorus]

Peachy

I’m feeling peachy keen

When she’s with me

My life feels a dream

And if I’m sleeping

Or just Imagining

Then she’s the greatest thing that I ever come up with

[Post chorus]

Peachy keen

Peachy keen

Peachy keen

She’s the greatest thing that I ever come up with

[Verse 1]

I watch her eyes glance at my lips

I watch her heart start yearning

I watch her pulling all her tricks

And I’ll admit it’s working

[Chorus]

Peachy

I’m feeling peachy keen

When she’s with me

My life feels a dream

And if I’m sleeping

Or just Imagining

Then she’s the greatest thing that I ever come up with

[Post]

Peachy Keen

Peachy Keen

Peachy Keen

She’s the greatest thing that I ever come up with

[Verse 2]

I feel our song play quiet now

I feel her disembark

I feel our fire fading out

As she leaves me in the dark

[Instrumental]

[Chorus]

Peachy

I’m feeling peachy keen

When she’s with me

My life feels a dream

Guess I was sleeping

Or just Imagining

Cos she’s the greatest thing that I ever come up with

Our story drove the song, and it went from being about the joys of having a crush on a girl, to the problem behind putting someone you like on a pedestal. I solidified this with a slight change of lyrics in the final chorus.

Peachy

I’m feeling peachy keen

When she’s with me

My life feels a dream

Guess I was sleeping

Or just Imagining

Cos she’s the greatest thing that I ever come up with

At the beginning of the writing process, I was writing something catchy, uplifting and flattering for this girl who I had an ambiguous relationship with. Then as our relationship progressed, it turned into an upbeat love song, and as our story came to an end the meaning of the song changed from being about falling for someone into being careful not to romanticise someone before you know them. By allowing the song to naturally change and follow the story of the relationship it becomes authentic.

I could have finished the song immediately after I started writing it, or while we were in a relationship together or any of those stages. In doing this the song would still be authentic in that my feelings were genuine and it would have been a timestamp of where we were and where my head was at. To me, it didn’t feel right at any of those stages because I felt that my brain was missing vital information.

Epilogue

There is no real right answer, that's the beauty of songwriting, it's like a puzzle with multiple pieces that fit. You get to choose what you want it to be! My advice would be to serve the song, not your ego. Everything should be connected and have meaning that drives the song towards the point. Support your ideas and make them feel natural. Serve a musical purpose. When you’re finishing up a track, don't be afraid to kill your darlings OR relocate them. Don't do a disservice to the song, you can always use incompatible ideas in a later track.

There is so so much more to talk about on each of these topics but I hope that I’ve gotten your brain ticking and you can find a helpful application amongst all the information here.

If you have made it this far or found any of this information useful, please consider leaving me a tip! You can also check out any of my socials via my link tree for more songwriting tips and behind the scenes content. My debut EP titled “Not For Me” is due to be released August 27th of this year.

Thank you so much for reading and I wish you all the best on your songwriting adventures. Feel free to reach out if you have any questions or want to show off your work!

Sending you love,

x Mouk.

About the Creator

Mouk.

A head and heart-strong musician and writer. Mouk.’s work focuses on strength through vulnerability, growth, queer love and community.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.