Standing on this bridge always had an effect on him. The cranes and superstructures of the port in the distance, the mist rising off the river in the gloom, and the muffled noise of traffic that seemed to dissipate into nothing when he reached the very middle of the span, where the water appeared to loom closer rather than further from where he stood. If he reached out a hand, it might be possible to wet it in the river’s inky thickness, wet it with the slowness and chill of fluid that seemed like anything but water.

From here, the world seemed a manageable place; put together for his purposes. A harbour for the sanctuary of ships, a port for transportation of all that was necessary, and houses that crowded close to these places of buoyancy and plenty. Even wading birds and ubiquitous gulls seemed confident and less predatory here. The red feet of some sort of water fowl squelched and rattled over mud and grey pebbles, and glistened an oily sheen under lights coming on in a necklace around the boundary road.

If I were Lowry I would be happy now, he thought. If I were Lowry I’d take all this home and quickly set it upon a prepared canvas, complete with a prim and upright signature, and send it by courier to the gallery at the end of the week, when it was dry and when I thought it portrayed all the peace that’s necessary in my mad, mad life.

He could not paint, of course. The only thing he could do with reliable certainty was express his dreams in words: set them upon a screen that glowed, night and day, in a darkened room cluttered with a fortnight’s worth of mugs and glasses, plates and empty jars of pickles. Mad, mad.

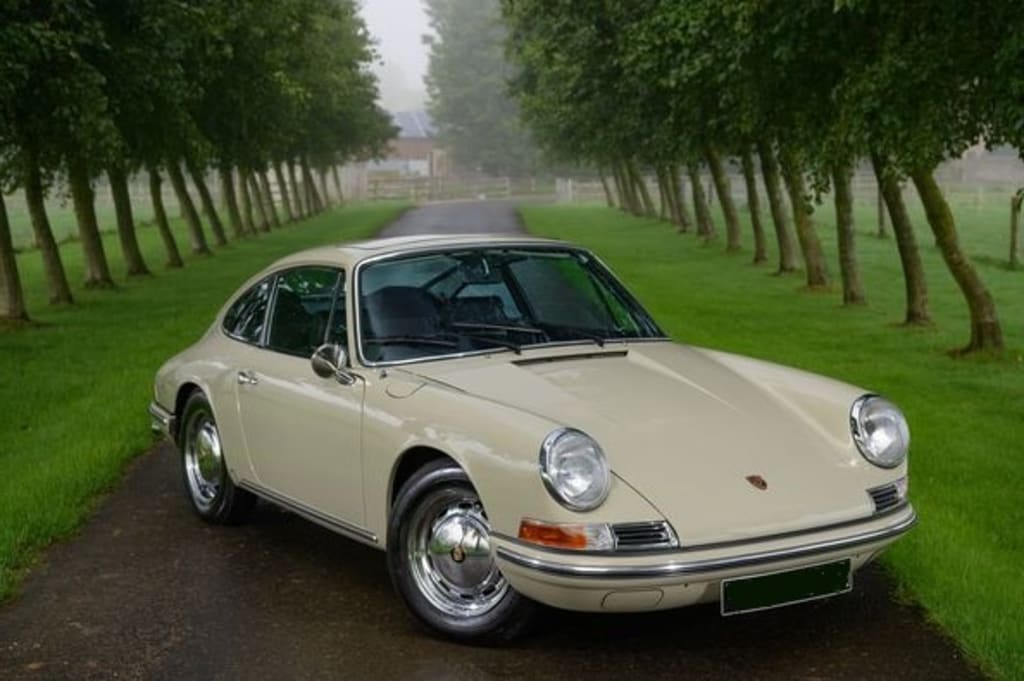

He wrote about dancing, of all things; ballroom dancing. Its music, its costumes, the dancers that flocked to the halls and competed, with numbers on their backs. What he knew about it from first-hand experience could be narrowed down to that fateful visit about twelve years ago – well … it felt like twelve years – when he first saw her in that dull beige Porsche.

Walking off the bridge to the other side, back to the tumult that was Crannock Place; to the noise, the bustle and the double-parked jalopies, he thought of that night, and of what followed. What it was that drove him to writing about things, instead of living them. He rolled his eyes at the darkening sky, and pictured her as she was then.

A full skirt; that was what caught his eye. It was so unusual, so old-fashioned, like something unreal, transported from one of the 50s magazines his grandmother still kept in the cupboard under the stairs. Tulle, he thought the net fabric was called. Tulle: in layers, like froth: pink, white, orange and some other colour with a strange-on-the-tongue name. Her hair was piled on top of her head and lipstick glowed on her mouth. She pushed the door of the Porsche shut with the toe of a red shoe. Red, red shoes, with heels so high and insubstantial that surely, she had to walk on the balls of her feet to save breaking them. But no – she gave one backward glance to check whether she had parked hard up against the pavement and walked jauntily away. Then suddenly dove into a doorway, over which he read Carnival Ballroom – Dancing for All Ages.

Going through that door after her – watching her red shoes tip-tap rapidly upward, on stairs high above his eyes – was the beginning of something other-worldly. The music reached his ears suddenly, and then stopped as the door above swung back behind her. She had arrived – but he stopped to think. Martin Cooper, you stupid man. What are you doing following strangely dressed women into buildings you have never remarked, let alone entered?

He had never noticed this dancing school. Yet the muted lights and dull sounds that came through that door were potently attractive. What if he pushed it open and let himself into the lights and sounds, announcing he wanted to learn too?

Learn how to dance? It was crazy. He had never entertained the notion of ballroom dancing. And at his age, it was ludicrous. That woman could not have been older than … thirty? Twenty? He looked at his shoes and thought about his age, her age.

‘Hi! Coming in?’ A voice behind him boomed in the stairwell, male and blustery.

‘Um, yes.’

It was a big room; enormous, with sparkling girls gathered at one end. They were brilliant, like wading birds, top-heavy and scintillating in pastels. Froth and dazzle, tulle and sequins that bobbed and shimmered as they pecked and preened each other. They gazed into the wall of mirror and sleeked back hair, patted a bouffant, fluffed out a skirt or adjusted a strap, while a gaggle of boys watched with faintly interested eyes. They were just as vain, combing hair back and pulling at lapels, while some brushed the toe of a shoe against the back of a trouser leg. Toe against calf, calf against toe.

‘If you’re new, you register, you know.’ A girl in a cardigan that clashed with her green dress elbowed him in the arm.

‘Thank you.’

‘Sure.’ She winked and went on to chew her gum, confidence oozing from her like a thick perfume.

Across from him, two men argued over records, writing a list. One put on something that sounded like a tango, or a cha-cha. How was Martin to know? Gran would say things when she played the radio, but he never really listened.

The voice that boomed on the stairs spoke into a microphone. ‘Take your partners for the two-step and the foxtrot, please.’ A cough, and then, belatedly, with a comfortable grin, ‘Good evening, ladies and gentlemen.’

A general titter gave way to a bit of a shuffle as boys approached the bubbly crowd of girls, and there she was, all orange and pink and white, twirling at the hand of some Elvis in a cream suit, a black shirt with an enormous collar, open at the neck to show a chunky silver chain. A walking cliché, Martin thought, but could not take his eyes off them. Her red shoes were a blur as she danced. It was impossible to say, but she looked good, better than some others; more confident, at any rate, and one of the few not chewing gum.

There was a groan when the music changed, but all danced on, with only two or three watching, without much interest except for Martin, mesmerized, immobilized by the show. He had to do something, unless he was going to seem like a voyeur, a simpleton, a blow-in from the street with nothing to say for himself.

Before the set finished, he walked over to the woman at the table, who smoked a small cigarillo in a holder and blinked at him. ‘Not seen you here before.’

‘No. Um…’

‘Two pounds for three nights, love.’ She inhaled deeply, and spoke through smoke. ‘Or seven for twelve. Up to you. Fill the form, and…’ She sized him up. ‘Ever danced much?’

‘I… no.’

‘Gloria will take you then. She’s coming up for instructor. Really good.’

‘Gloria?’ He put notes on the table and scribbled his name on the form, wrote his street name and put a small slanting flourish on the last line.

‘Yeah. Like I said. Really good. That’s her now.’

Martin turned and she was standing there, smiling. Red shoes and frothy dress.

‘Gloria.’

The older woman turned the form round and read the top line. ‘Show Martin here a jive, and perhaps … You decide, darling.’

Gloria did all the deciding. She showed him a jive, and they tangoed, waltzed and two-stepped for three weeks. Everything else vanished into the music. Pound after pound went down on that table, and Martin could do the paso-doble, complete with tour jete and a full lean. He was not entirely sure Gloria pronounced the words in the right way, but it was not important. He found he could dance, and he could see – even in her hooded eyes that never rose past his chest – that he pleased her.

Facing the night alone each time, walking along the river, the smell of the room still in his nostrils and reluctant to get home, he would saunter, hands in pockets, and think of Gloria in pink tulle, and yellow georgette, and aqua lace, and lilac shantung. Think of her clipped sentences, her avoidance of eye-contact.

She was in cherry georgette, with a black velvet choker and her hair pulled into a loose knot on top of her head when he asked if she would like a Coke afterwards. They had just finished a set of six, and he was breathless, but victorious, having brought off a cha-cha and a jive without losing her, or confusing the count, turns, or rhythm.

‘A Coke?’ Her face lit up and for the first time, he felt the force of wide grey eyes, looking straight into his own.

It took his breath away. ‘Or anything else you might like.’

‘You might like a ride in my car after that fandango tonight. Then you can buy me a cocktail down at Riley’s.’

Martin blinked. Of course; a cocktail. Of course, Martin Cooper, you stupid man. She had hardly spoken anything in three weeks but instructions. ‘Two steps left like this, orright?’

He would look at red shoes, or green shoes, or beige shoes the colour of her car.

‘Once back and once forward, then a hop, step and slash, orright?’

Now he looked into wide grey eyes and followed her to her Porsche.

Was it a dream? No one had a Porsche. Yet he would watch her drive up every night, the car glistening in the rain sometimes. He arrived early, stood at the corner and paused while she got out, adjusted her skirts and pushed the door shut with a pointed toe. Then he followed at a brief distance, and heard her tap rapidly up the stairs to the door, sometimes joined by a couple of other girls, or that Elvis in his white suit.

When she danced with someone else, or gave instruction to some couple, he would observe her straight fringe, the thick make-up on pale cheeks, which filled out small acne sockets. Brilliant pink lipstick, which she checked in the mirror every five dances or so, was always the same shade; but her eyes were sometimes feathered in bright green shadow, or dove grey that made her look like a sleepy peacock if she wore the lace dress.

He led her out to the centre of the floor and she would tut-tut. ‘That’s for when you get better at the merengue, orright?’ So they kept out, in the wide circle, skirting the floor, where he could see some boys’ eyes following them. He soon saw they looked at his feet, not his face.

Was that all he remembered? It was a blur now, but he wrote and wrote, and made lists of all the words she had said, leaving out the ‘orrights’ and checking the spelling of the outlandish names for dances she invariably pronounced wrongly. Habanera, malaguena, passacaglia, zapateado. He doubted, after such a long time, that they were dances he executed with her. With Gloria, it was a matter of getting the one-step right, and the foxtrot, and she would nod and remind him of the count during the jive.

‘We’ll demonstrate a slow waltz tonight, orright?’ Over-the-shoulder words to him as she checked lipstick in the mirror that duplicated everything in the room; even old Marcia as she checked lists and took money, and squinted through cheap cigarillo smoke.

How had a cocktail rather than a Coke led to such pain? Martin did not want to relive the humiliation, but writing it out would ease the discomfort, perhaps. That’s what they said; writing things diluted them, or made them more real … or made them hurt more, perhaps. Anger fizzed in his chest and he spent more and more time inside, in the dark, behind drawn blinds, staring at the green screen of an unaffordable processor that had dragged him willingly into debt because it gave him something else to concentrate on. Something other than step, step, step, lunge and slash, two-three-four.

There was a screen, and there were words to put on it, taken from a stack of books on dancing from the library, three corners away from the dance studio, where he never went again. And there was the river of course. The river at night, and the bridge that gave him moments of dull silence and the chill and smell he could rake fingers through. There was the bridge, see? It gave him a sense of being grounded in a place of substance and plenty.

No need to think any more of paso-doble or waltz. How she had wounded him. Just as if she had stabbed him in the chest with one of those thin deceptively weak-looking heels. Those shoes. He remembered her slipping them off and carefully placing them side by side at the foot of a bed. The full skirts somehow found themselves neatly folded over the arm of a dressing-table chair, in a movement that set cheap scent bottles tinkling against each other in the theatrical light of a dozen naked light bulbs run around a mirror, and an animal print shawl thrown over a standard lamp.

He could write about that room, and did; described the streaks of damp on the walls, behind the posters. Described the bathroom so tiny the door was only inches from his back when he relieved himself of beer and what passed for cocktails at Riley’s, and peered at the small mirror over the light green sink. Described the bed made up so tightly she wrenched away the covers with a grunt each night.

The rides in that car. Oh, it was a beautiful car, she would say, but wasn’t worth the amount of petrol she had to pour into it. Would have preferred an Allegro or a fab little Mini, or even a TR6.

‘A TR-six?’ Martin repeated what she said, feeling stupid.

‘Just dreaming, orright?’ Gloria would laugh and throw her head back, as if a Porsche were not astounding enough, and park close to the pavement, sometimes taking the near wheels right onto the footpath and squeezing past him as she led him in, and onward, and down.

Down, he went, into depression and a slight feeling of nausea as he wrote how she deluded him, and how she preyed on his loneliness and bewilderment. Her dresses. Perhaps it was her dresses that did it. Her wardrobe was large, antique, and made of very good cedar, she said, to deter moths. Crammed into it were voluminous skirts that pushed at the door, wanting to be let out into the music and the lights. Tulle, organdie, lace and taffeta.

She said the words to him, and he was sure she said them wrongly. But he wrote them down. He tapped them into that expensive machine that demanded more and more of that blasted thermal paper on a roll that darkened if exposed to sunlight on a windowsill. He would not leave it there again. He would draw all the blinds and protect his paper and himself.

Protect himself from taffeta, georgette and shantung. If he could paint like Hopper, now, he might excise it all in a series of paintings. Cut her out of his life with a scalpel, and flatten her onto a canvas with her skirts and her heels. Her step, step, hop, slash. Her ‘orright?’

It was easy, and stupid, and hopelessly mad to buy a large book of Edward Hopper paintings, cut out all the colour illustrations and stick them on the walls of his darkened rooms, where they loomed out at him the instant he clicked the lamp on, a lamp he draped in an old length of silk he found in the same charity shop, that smelled of mothballs, orange peel and rough-dried, incorrectly stored old clothing. Gloria’s place never smelled like that. The first time she led him in, after getting out of the low-slung Porsche, dizzy from the ride and the possibilities that yawned from the first direct glance he had of her grey eyes, he was struck by the presence of clean, cheap scent. The smell of soap, of camphor disinfectant, of something sharp like peppermint or pine.

He had her in that smell; completely, he thought. She sighed and he thought he had her. Gloria was willing, and greedy, and bounced lightly on that tightly made-up bed. The animal-print scarf threw streaks of brown light onto the walls, which the morning faded and turned ugly. Beige, like her car. Where had she got that car? And how?

‘I want some money, love. Orright?’ The smile was perfect, the lipstick pink. The eyes were averted, feathered in grey and directed at the mirror on the dressing table, which was low, and made her stoop. In ordinary street clothes she looked plain, almost disfigured. Sensible shoes did not go with those perfect calves and turned out toes.

‘Some…? For …?’ Martin was entirely thrown off. It had seemed like five days of magic, of paradise and perfection all rolled onto a well-stretched sheet. Automatically his hand went to his wallet and he looked with a great deal of puzzlement and incomprehension at the notes he found there. They were notes he drew out at a bank teller counter, happy he could afford another twelve sessions of dance. He was going to give them to Marcia on Wednesday night. She would wink at him through cigarillo smoke and nod at him to fill another form.

‘Still happy with Gloria, dear?’ Her question would be superfluous, a formality.

He would step past that Elvis in his black shirt and silver chain and hold out his hand, and she would take it, to sweep around, tulle skirts rustling, and wait for the cue so she could step, step and slash, orright?

‘Some money, Gloria?’

Her gurgled laugh was uncomfortable. She stretched to her full height and he looked at her ordinary clothes: a grey A-line skirt and a twin-set. With beads, a cliché from his gran’s time. Plastic graded beads to look like pearls.

‘I prefer you in tulle,’ he said. What else could he say?

She put out a hand and into it, he placed three crisp pound notes. She twiddled the fingers of her other hand and set her head sideways, as if to say, ‘Come on, now.’

Three more pound notes and she smiled.

‘Gloria…’

‘What – what?’

‘The … the Porsche.’

‘It’s Alastair’s, orright?’

‘Al… who?’

‘What do you think I do this for, love – the happiness?’ An unstressed word: a word he would never ever use again, in writing or otherwise. A word he refused to admit existed.

Down in the street the beige car was the only one left, parked with two wheels on the pavement.

‘Want a lift to wherever you’re going? I’m ever so early.’ Lipstick glistened in the morning light. It was a nightmare. A state in which he kept himself, stunned, placing notes into an outstretched hand, for another twenty-four months. A nightmare he would have excised, if only he could paint.

Standing on this bridge always had an effect on him. The cranes and superstructures of the port in the distance, the mist rising off the river in the gloom, and the muffled noise of traffic that seemed to dissipate into nothing when he reached the very middle of the span, where the water appeared to loom closer rather than further from where he stood.

If he listened hard, he might hear The Platters or Ritchie Valens, or perhaps the strains of some Victor Sylvester number that would turn him inside out. You see, it would make him smell cheap scent again, and hear the rustle of taffeta or perhaps tulle. He would see white and pink froth and see her as a top-heavy wading bird when she took his hand and he could lead her to the middle of the floor as the opening strains of a cha-cha filled the room, from the top of the full-wall mirror to the squeaky timber floor.

He knew he was only buying her, only furnishing Alastair with the wherewithal for some other, newer, car. One without ugly beige paint, a cracked gear lever, and dents in the bonnet; one that made less noise, used less fuel, and had comfortable seats. Only living a nightmare of envy, jealousy, suspicion, distrust and possessiveness that caught him by the throat every time she said, ‘Not tonight, Martin.’ Without looking him in the eye. ‘Not tonight, Martin, orright?’

From here, the world seemed a manageable place, but for the looming shape of that beige Porsche in his mind. The one she loaded him into, like some cargo, some necessary man in the passenger seat, who would willingly fold pound notes onto her palm in the morning, when he saw the squalor and meanness of her twin-set and pearls.

If he stretched his hand into the dark, perhaps he might feel the inky blackness of the fluid river, which could cancel everything with its chill.

This story appears in the collection The Red Volkswagen and Other Stories.

© Rosanne Dingli Yellow Teapot Books

About the Creator

Rosanne Dingli

Rosanne Dingli has authored more than 20 books of fiction, including 6 volumes of short stories. She lives and writes in Western Australia.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.