Strange Disguise

Breaking Boundaries in the Old West

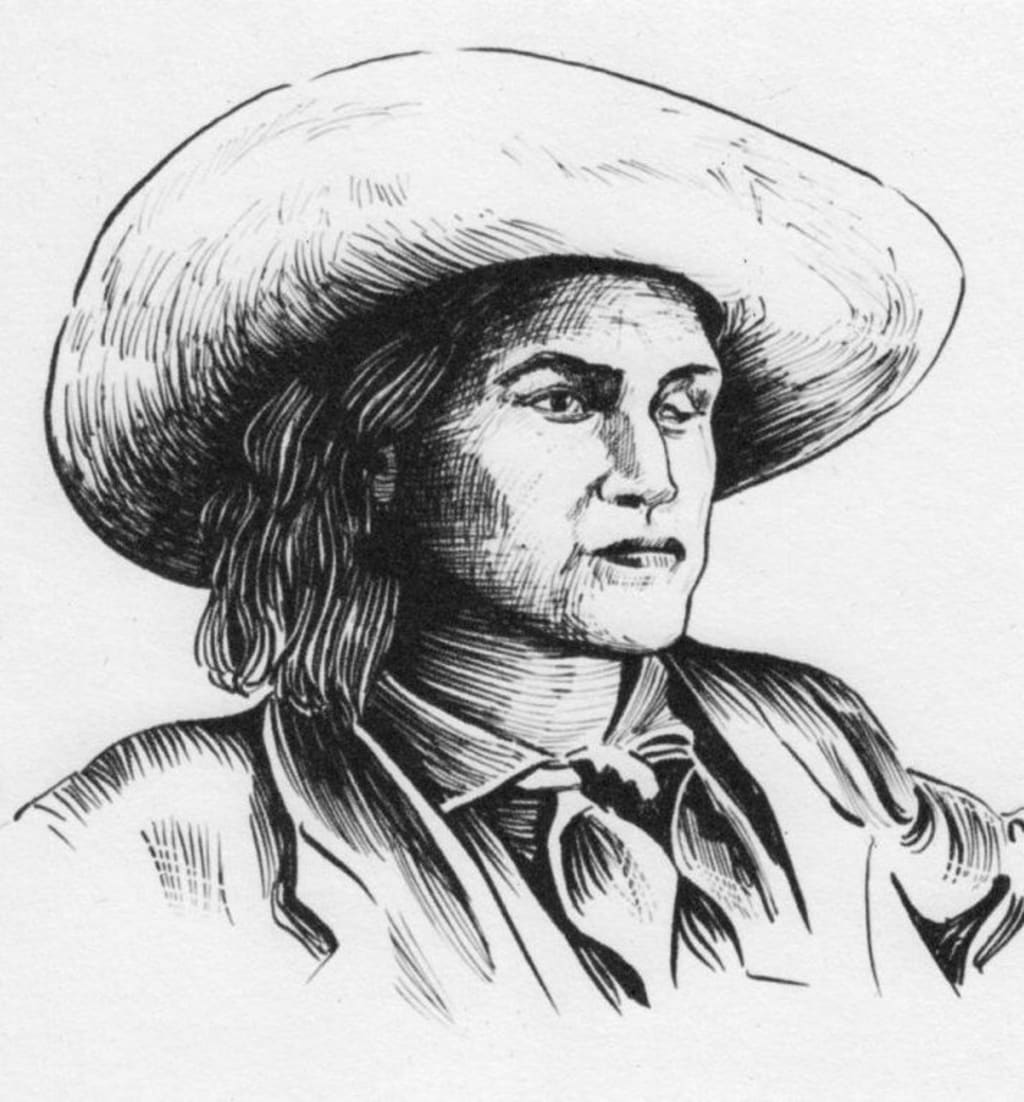

Charley Parkhurst was a badass, no one disputes that.

In California, during the gold rush, few professions garnered more respect than that of stagecoach driving. Only an elite cadre of skilled professionals had the dexterity to drive teams of six horses (or mules) on mountain roads that were more like trails, crossing flooded rivers and skittering along cliff edges. “Mountain Charley,” also known as “One-Eye Charley” after being kicked in the eye by a horse, was one of the best.

Bearing not only passengers but gold bars over a desolate terrain populated by desperados was a treacherous business. Charley’s route led through a portion of the Sierras controlled by a bandit known as “Sugarfoot” who one day relieved the Wells Fargo company of $42,000 in gold (worth over a million and a half today).

“Okay, Sugar,” Charley reportedly said, “You got the drop on me this time, but next time I’ll be ready.”

Sure enough, not content to retire and live off his haul, Sugarfoot tried his luck again, and was rewarded by both barrels through the chest.

On another occasion, a gun wasn’t even necessary. Charley’s whip struck a robber in the face, blinding him in one eye, while the stagecoach rolled along without a stop.

These feats of derring-do would be sufficient to earn a few lines in the histories of the Wild West, but the real reason Charley is remembered happened after death. On December 24, 1879, Charley’s secret was revealed.

As the local paper, the Register-Pajaronian, put it, “When friendly hands prepared the remains for their last home, the discovery was made that the body was unmistakably that of a well-developed woman. It could be scarcely believed by persons who had known Charley Parkhurst for a quarter of a century.”

The medical examiner further stated that at one time Charley had given birth. Among the belongings in the cabin was a baby’s blue dress.

In the 19th century, people didn’t know quite what to make of Charley Parkhurst, and we still don’t. The Pajaronian asked, “What reason was there that led a woman to exist so many years in such strange disguise? Was she disgusted with the trammels of her sex?”

The Rhode Island Herald wrote an opinion piece stating, “The only people disturbed by the career of Charley Parkhurst are the gentlemen who have so much to say about . . . ‘women's sphere' and the 'weaker (sex).’ It is beyond question that one of the most . . . celebrated of the world-famed California stage drivers, was a woman.”

The Record-Union in Sacramento was also supportive but had a different take: “In her case,” they wrote, “it is evident the masculine character is present in the fullest sense. Such a woman is very much more a man than anything else. In adopting male clothing and habits, she only obeys the law of her nature.”

To write about Charley Parkhurst today is to walk through a minefield. Charlotte “Charley” Parkhurst is remembered as a “well-known whip” of the stagecoach era, but also for being the first woman in America to cast a ballot in a presidential election (November 3rd, 1868). Several publications about “Women of the Wild West” include her story and hold her up as an example to young girls about what can be accomplished with grit and determination. Like the editors of the Herald, their point is that notions of limitation imposed on the “weaker sex” are shattered by the actions of this person who was "beyond question" a woman.

Wikipedia, and just about everything written after 2020, refer to Charley as a man who was “assigned female at birth” and use exclusively male pronouns. Like the editors of the Record-Union, they view Charley’s “male clothing and habits” as proof that he was “more of a man than anything.” There is logic to this: the sheer length of time that Charley “presented as a man” would tend to support the idea that he saw himself as one.

But we don’t know.

Was this “strange disguise” self-expression or armor? Was Charley a man “trapped in a woman’s body” or a woman who valued her autonomy and freedom more than the trappings of 19th century femininity? If she could have led the same life of adventure as Charlotte, would she have done so?

The final irony here is that the strange disguise wasn't really a disguise at all – it was pants, a shirt, and a haircut. Had Charley stayed Charlotte, that’s when the disguising would have begun in earnest. Bustles and corsets with whalebone stays to contort the body, rouge and powder to hide her face, and above all meekness to squelch any display of the brashness that came naturally to a woman like Charley.

About the Creator

Andy Waddell

Retired teacher, aspiring novelist, amateur actor in Santa Cruz, California.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.