Kolam and the Art of Loving One's Home

For value is determined by our daily decisions to live and love well.

Crossing ten time zones in a day can really do a number on a kid. Madurai, India was 10.5 hours ahead of my home in Maryland, and after 26 straight hours of travel by planes, trains, and automobiles, my eight year old circadian rhythm had no real placement of space or time. My mother, father and I were just three travelers, flitting indefinitely through clouds, terminals and paper napkins, with only the airplane's old Hallmark movies to comfort us. Then just as I came to the bitter acceptance that this eternal state of transience was our life now, we stepped out of a white taxi car in front of my grandparents' house. "Welcome home!" they said. I was back in India after 4 long years and was presently regaled with promises of how many wonderful experiences I would have there. So many things to see and taste! So many people to remember and love! And of course I remember all those things, and love all those people, but one of my most enduring memories came accidentally. It was granted to me by that great disrupter of circadian rhythm--jetlag. As strange as it may sound, jetlag was, and remains to this day, one of my favorite things about visiting India. It allowed me to nap through the hottest part of the afternoon, sleep around 1am, and wake up again just before dawn.

I woke up this way the day after we arrived. I sat up in my bed at 5am, in the only A/C room in the house. My grandfather was snoring on a bed in the opposite end of the room. My father lay on a mat on the ground next to me. My mother, with whom I shared a bed, was nowhere to be found. I rubbed my eyes and slid off the mattress, tip-toeing around my father and out the door. In the hall, a noisy ceiling fan whirred over the cot where my grandmother lay. I had to be quiet here too. With nowhere left to go, I opened the hallway door to the veranda. The morning air was cool and clean. It was fragrant with the smell of water and green coconut leaves. A gentle breeze brought a sudden burst of jasmine scent, but drew it away just as quickly. Outside, birds had begun their morning routines and called out to one other in the trees, welcoming the first faint streams of color from the sun. My mother was already awake. I found her sitting on a wicker chair in the veranda, drinking coffee. She smiled to see me.

"Awake so soon?" she asked.

I nodded and stretched dramatically.

"Here. Taste this coffee," she offered, "it's not like the coffee in America. This is the best coffee in the world. See? It even smells different!"

I took a sip and shrugged. "It's okay, I guess."

My mother snatched back the coffee and shook her head, "A donkey couldn't appreciate the smell of camphor."

"What does that mean?"

"It means you're a donkey," she replied solemnly.

I doubled over in laughter at the thought. Through my fits of giggles, I shoved my face next to my mother's and managed a weak "Hee haw! Hee haw!" in her ear.

She chuckled and pushed me away. "Let me finish my coffee, donkey, since you don't like it."

I hopped up on the chair next to hers, still giggling madly to myself.

As dawn gathered it's strength, we could see faint movement stirring around us. A light turned on in a house nearby, and we heard the rattle of keys opening a metal lock. Here and there, a car horn blared in the distance, and we could soon hear cows lowing in the water field down the street. My mother finished her coffee and stood up.

"Want to go to on a walk?" she asked. I jumped up eagerly but looked down at my pajamas.

"Like this?"

"It's okay. No one minds here."

We set off on our walk through the neighborhood. I stopped every few feet to inspect the flora and fauna and provided my mother with a running commentary on my findings.

"The plants are all different. Look, Amma! A lizard! It's so cute! The squirrels are so small here! Wooaahhh, but the crows here are way bigger!"

My mother was uncharacteristically patient with my explorations. She was also taking everything in. She observed the street where she played, the homes that had changed, and the trees that had grown over the years. She needed more time, perhaps, than I did to process the sights on our walk. How much things had changed, and how many more things needed to change still, she thought. Oblivious to her bittersweet musings, I continued my noisy descriptions of the local wildlife. I paused though, when I saw a woman standing in front of the next house we approached. She was bent down low in front of the metal gate with her hand extended to the ground. She looked to be drawing something on the ground with her fingers.

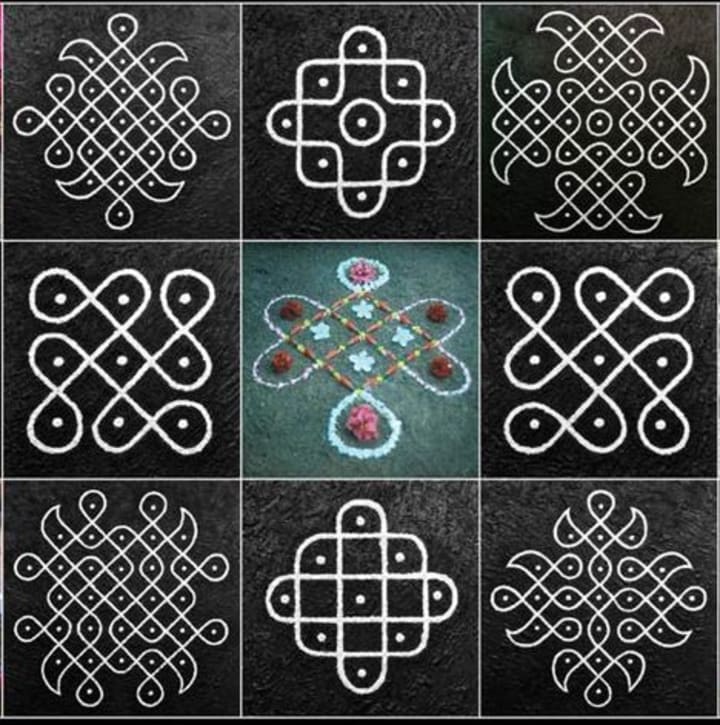

I walked a bit closer and saw that she had made a pattern of dots on the ground with some white powder in her hand. Five lines of five dots each--a perfect square. Every now and then, she reached into a pouch for more powder. I watched, mouth agape, as she slowly connected different dots, making rounded shapes at the edge of the pattern. A beautiful geometry suddenly emerged. It looked like a square of four ropes interwoven evenly with one another, flanked by four identical flowers at each corner.

I couldn't help but gasp aloud in amazement. She had done all of that within a minute! The woman turned and smiled at me. "Do you like it?" she asked? I flashed her a gap toothed grin, and nodded shyly. She motioned for me to come near and look closer. I circled round and round the design, taking in the intricate details.

Soon, the gate of the house next door opened too. A young girl, about 16, came out and waved to us. With a broom, she dutifully swept the entrance to the house gate, and then took out a small box. She opened it and bent down, creating a similar set of dots on the ground. She made seven rows of seven dots. She took a bit longer, but as she connected her dots, she made larger curves around her design. She created a circle of soft waves inside her circle, with flourishing petals extending all around it. In a matter of minutes, she had created a giant flower, taking up the whole entryway to the house.

I grabbed my mother's hand and shook it urgently. "What are these?" I whispered.

"It's called a kolam," she replied.

"What's a kolam?"

"It's the design they're making. They make it in front of the entrance of homes every morning."

"Why?"

"It's part of our culture."

"What is it for?"

"It shows that the house is loved," she replied, "and that the people who live there are taking care of it."

"Then why don't we have it in front of our house?" I demanded.

"Because we're Christian, and kolams are usually done by Hindus."

"Is it against the Bible?"

"No, no. We usually just do it on holidays and special occasions."

"What is that white powder?" I continued.

"In the past they used rice flour, but nowadays most people just use chalk powder."

"Why don't they use rice flou---"

My mother sighed. "Enough questions. Let's keep going, you'll see all different kinds of kolams."

And we certainly did. Different designs, colors, sizes--all done early in the morning by women associated with the home. I skipped down the street ahead of my mother, stopping to admire each kolam in the neighborhood. When we circled the street and made our way back home, my mother went into the kitchen and brought out a cup of rice flour for me. Taking the cup gingerly, I squatted at the front gate to begin my artistry.

"Wait, wait!" my mother called. "You can't make a kolam on a dirty entranceway. Sweep it first, then draw."

I nodded and retrieved a broom. With more gusto than I had ever exhibited in chores before, I swept the large entryway clean. My mother leaned against the gate next to me, occasionally pointing out spots that I had missed.

Then, cupping the flour in my hands, I created a wobbly 'V' and two uneven curves over it, forming a lopsided heart. Using my fingers, I carefully filled in my heart with the rice flour. I turned my head to look at my creation. It wasn't very fancy, like the other kolams. I pinched some more flour with my thumb and forefinger and drew several squiggly lines radiating from my heart. I looked up at my mother, who nodded in approval.

"It looks very Catholic," she affirmed.

"Are we Catholic?" I asked.

"No," she replied, "but we're close enough."

I smiled contentedly, and admired my heart. A motorcycle soon sputtered past us, kicking up dust from the road, and stopped in front of the house where we first saw the woman drawing her kolam. A young man got out with a small package under his arm. With no second thought, he walked up to the gate and rang the bell, stepping squarely on the beautiful design the woman had made. I gasped in horror at his affront to the arts. The woman came to the gate to receive the package. She thanked the young man, and handed him some money. He waved goodbye, stepped back on the kolam, and revved up his motorcycle to leave. The woman didn't seem to notice that he had walked casually over her hard work. I looked up aghast at my mother.

"He's ruining it!" I hissed to her.

My mother only laughed. "He's not ruining it," she said. "It's meant to be walked on. That's what it's there for."

I shook my head incredulously. "No, look!" I pointed, "the flower's all smudged."

"Baby, they make kolams every morning to show that the house is ready for visitation," she assured. "It's meant to welcome people. Over the course of the day, as more people come, it will fade away. Then the next morning, they make another one."

"They can step around it!" I insisted, "she worked so hard on it."

My mother shook her head. "No." she said firmly. "The kolam is not meant to last for long. It's meant to be created afresh every day. We need to work every day to maintain and take care of our home and family. The kolam is just like that. Every day, we need to spend time to show that we are taking care of our home. It's a good reminder for us, and the people who see it, too."

My mother stepped through the gate entryway towards my kolam. Realizing what she intended to do, I huddled in front of my heart, like a dragon protecting its treasure and scowled up at her. She chuckled and reached for my hand, pulling me up.

"Come on," she urged, "we can walk over it together, like a real kolam."

Reluctantly, I tip-toed across the heart, trying my best to touch the blank spaces between the radiating lines. My mother exhibited no such restraint and stepped right on top of it. I frowned disapprovingly.

"Good job!" my mother said, clapping her hands. "You've made your first kolam." I smiled begrudgingly, and squatted down again to fix the damaged heart. My mother shook her head and went inside the house, where everyone had woken up.

I kept some rice flour in a box in the veranda, and every morning after that, swept the entryway clean. Then I would squat down and create trees, stars, flowers, and geometrical shapes. My grandfather went to the shop and brought back a pack of chalk powder, in blue, green, yellow and pink. I kept these safely in my box, and added color to my increasingly intricate designs. The neighbors all smiled to see my bizarre drawings in the front of the house, and would often stop to talk to me. They asked me questions about America, and how I liked India. They all said they remembered when I was a baby, and asked if I remembered them too. I never did.

Then they would laugh, and say, "That's alright. We remember you from when you were a baby, and now we will remember you drawing so many beautiful kolams in front of the house."

I would nod and smile at them, and they would continue their strolls down the street. Now that I think back, most of those wonderful people have passed away. Those that remain are old and diminished in health. They, and the memories of them that remain, have faded away like the kolams they drew before their homes for so many years. But everyone there knows that the fading of brightness and beauty is a natural progression of living a good life. Every morning, we must make a decision to love and care for what is around us, and understand that though our work, and that which we love, may fade, the effort we put into them defines their true worth. Their value is immutable until we decide they are not.

Truthfully, I didn't learn any great lesson from kolams when I was eight years old. In fact, I didn't think about kolams at all after I left India. I started a new year of school, made new friends and continued my life with no greater measurable wisdom than before. I grew up, went to college, got married, had children, and lived my life the best I could. I didn't think about kolams again until a few years ago, when the birth of my second child brought about crippling postpartum depression. By April of 2020 I had tried multiple depression medications, gained several pounds as a result of them, yo-yoed in and out of suicidal ideations, and made multiple calls to the suicide hotline. The onset of the pandemic had further isolated me from much of my support system, and my depression was weighing heavily upon my husband and me.

On a bright April morning, I sat upon my front steps with my three year old son. We had bought him a pack of chalk, which was promptly spilled out, broken, and dispersed to various corners of the house. Two colors remained in the box. He drew on the steps for a few minutes before tiring of his activity. He threw one piece of chalk on the ground, turned to meet my eyes, and smiled slyly. Then he took the other piece of broken chalk and lifted it slowly to his mouth.

"No, we don't eat chalk," I offered weakly. But he knew I was full of shit. He popped the chalk in his mouth, turned around and bolted down the sidewalk, screaming with laughter. I threw up my arms in defeat and could feel the tears already forming in my eyes, but there was no time to cry--he was heading towards the road. I heaved myself up and ran after him, calling for him to stop. He was almost at the road by the time I caught him. I pulled him up by one arm roughly and dragged him back to the house.

"Ow, mommy! It hurts!" he protested, but I didn't care. He dropped his legs trying to slow me down, but I just lifted him by his one arm and continued back to the house with him wailing beside me. I hoped upon hope that the neighbors weren't watching. I opened the door of my house and shoved him inside, shrieking to my husband that I needed five minutes before I exploded.

Then I sat down on my front step and wept. I wept because I was too exhausted to feel any emotion besides defeat. I was tired of my life, my obligations, my marriage, my children. I was too tired to continue being me.

When all my tears were spent, I wiped my eyes and shook my head. I had a few more minutes before I needed to go back inside to nurse the new baby. I braced myself upon a stair to get up again when I felt a lump against my hand. It was a piece of broken chalk that my son discarded. I picked it up and looked at it. Just the week before, my friend had told me that I needed to find a grounding exercise--an activity I could turn to when I felt overwhelmed and needed to re-orient my mind.

"Have you tried drawing mandalas?" she had asked. I shook my head. She had bought some drawing paper and a set of colorful pens for me.

"You should try it!" she had said, "It's a great grounding exercise. It works pretty well for me. It's good to do it in pen, so you don't fixate on imperfections and try to erase it over and over again."

After she left, I had tried it for a few minutes, but never finished it. There simply wasn't much meaning behind it, and it seemed like a waste of time. So instead, I had picked up my phone and scrolled listlessly through social media, gazing at perfect, smiling faces that I didn't really care about. But here I was, with a piece of broken chalk in my hand, a tear stained face, trying to find a reason to delay going back inside my house.

So I slowly drew five rows of five dots. I tried to recall the design I saw the woman make 20 years prior. I remembered it looked like four interwoven ropes, but couldn't remember the details. I connected random dots with each other in curves. Then I drew circles around the four corners, and turned them into rough flowers. It looked uneven and messy.

It's still a kolam, I thought. It's made by a woman associated with the house, in the morning at the entryway. It meets all the requirements of a kolam.

I looked at it for a moment and got up. I opened the door and went inside, making sure to step on my kolam as I entered my home. I was ready to resume life.

Every morning after that, I did my best to go outside for a few minutes and draw dots, connect them and expand them into symmetrical beauty. I looked up designs and tutorials online, and found intricate patterns to follow. My neighbors began to tell me they liked the drawings they saw on my front steps. They said they always liked passing our house to see the designs I had done that day. I always smiled and thanked them, saying I was glad they liked it. My neighbors were white and didn't know the significance of a kolam, but despite that, it still conveyed all the important messages anyways: this house is cared for, and we love it enough to spend time to maintain it.

Happily, my postpartum depression eventually waned away with time. Kolams did not always provide an instant fix on bad days, but it did provide a brief few minutes of quiet for me. They were, as my friend said, a wonderful grounding exercise, rife with tradition, culture and meaning.

Every now and then, I still feel panicked itching inside my head. The voices of the people I love can still burrow holes into my brain, and the rooms in my house seem too small for all the noise they contain. In times like these, I reach for some rice flour, or chalk powder and create a pattern of dots--to remind myself that everything of value requires consistent effort--to remind myself that this house, and the family in it, is still loved.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.