'Haven't I Always Treated You Right?'

How "The Passing of Grandison" and "Get Out" Dismantle the Myth of the Good Master.

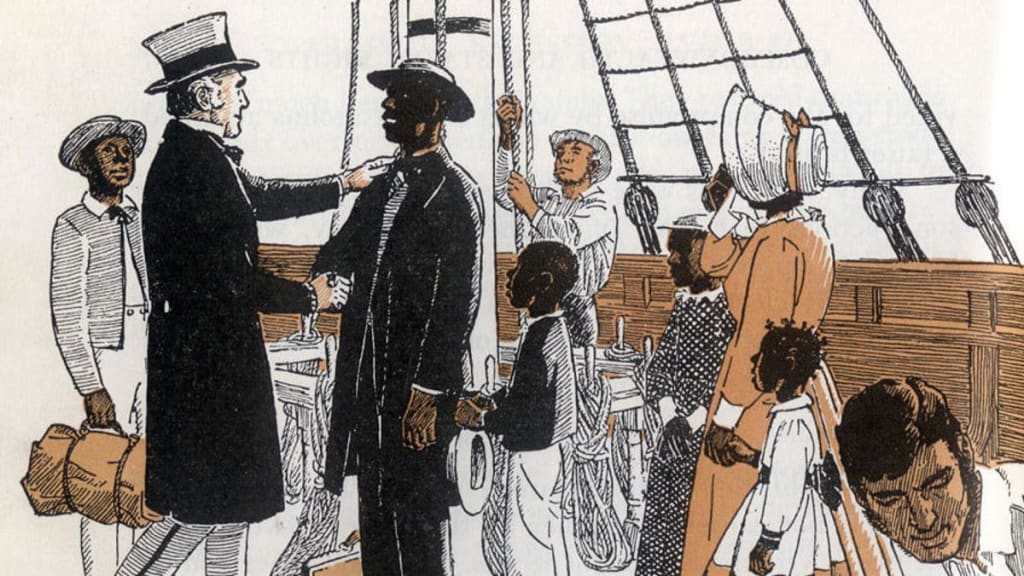

An elderly white man in an elegant black coat stands on the deck of a ship. He smiles warmly, patting the shoulder of the well-dressed slave in front of him. The African-American beams, his eyes shining with undying faith and adoration as he grasps the hand of his master. His bleached teeth are a sharp, cartoonish contrast against his dark skin. The Virginian children reading the textbook this picture is taken from cannot help but share his grin. What a happy sight! What a happy illusion. These instances of mistaking indoctrination for education have persisted far beyond Lincoln’s abolition. Recently, Scholastic came under fire for publishing a children's picture book depicting the slave Hercules and his daughter Delia cheerfully baking a cake for George Washington's birthday. America, a nation built on freedom, should condemn those who wield the lash. Instead, it praises those who restrain themselves from using it. Charles Waddell Chesnutt’s satirical short story and Jordan Peele’s horror film combat this with their own proposal: a beneficent master can never truly exist if they drop the charitable act as soon as they are a master no longer. This essay will argue that “The Passing of Grandison '' and Get Out tear down the fantasies of white supremacists, using allusion, irony, dialogue, and symbolism to expose the duplicity within their so-called justifications for the exploitation of black bodies.

The Bible is the most infamous propagator of said fantasies. The Confederate South omitted and altered information from the holy text to portray more sinful characters as darker-skinned, vilify all of their allegedly African descendants and cite it as "proof" that the colored had more need for redemption than the messianic white man (Rae para. 2). Bishop Stephen Elliot of Georgia insisted that by being made their property, their black laborers would learn the way to heaven and learn the very best lessons for a semi-barbarous people, the most notable of traits which they acquired being obedience (para. 7). On the one hand they could be talking about obedience to God, which is the actual message of the Bible, but its meaning could easily be distorted into black people being obedient to white people. For example, sadistic and saintly slaveholders alike were particularly fond of parables that encouraged the discipline of disobedient slaves (para. 6), or the rewarding of good and faithful ones.

On the contrary, it is important to note that the relationship between the black community and Christianity was not always completely antagonistic. As “‘Those Who Labor for My Happiness’: Slavery at Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello” describes, “...spirituality was an integral part of each day in the lives of enslaved African Americans, for whom the secular and sacred were intertwined” (Stanton 117). By hybridizing the religion of their colonizers with the supernatural, the plantation workers could stealthily practice and preserve the most important beliefs from their African ancestry, rendering their clueless captors’ attempts to assimilate them obsolete. Thus, it is only appropriate that Chesnutt pays tribute to this clever strategy, carefully blending his provocative parody with the Bible in his own way to make utter fools out of the Christian slave masters of old.

A week after Dick successfully abandons Grandison in Canada, his father the colonel returns with none other than the stubborn servant in his buggy. The colonel’s passionate retelling of how “Grandison escaped” (Chesnutt para. 116) is dripping with paradox. The first layer of irony is that the colonel believes that Grandison escaped from the Yankees when Grandison is escaping from him. The second layer lies within the many interpretations of the word “escape” itself. The first definition of “escape” is to break free from control, but instead, Grandison seems to have voluntarily returned to bondage. On the other hand, “escape” also means “to fail to be noticed by someone.” In these first two words, Chesnutt perfectly encapsulates how Grandison only snuck away from the Yankees so that he could sneak out the entire workforce of the plantation. By “keeping his back steadily to the north star” (para. 116) he is leading all of his companions toward the north and toward freedom. Like his African ancestors before him, Grandison has effectively turned his confinement into a channel for liberation.

The colonel also laments about Grandison suffering “incredible hardships'' (para. 116) before his return. The “hardship” that the colonel refers to is the difficulty of surviving in the frigid Canadian wilderness, but Chesnutt implies that the real hardship is the terrible nature of slavery itself. Even the placement of the commas in “his old plantation, his master, his home, his friends…” (para. 116) conveys a gap between reality and his power fantasy. This indicates that the colonel is at least somewhat aware that the plantation is not Grandison’s home, but his cage. As much as he may joke around with Grandison as if they were the closest of companions, deep down he knows that a master and a slave cannot be friends. In fact, he actively distances himself from the Other, so he can convince himself that he is above them. He does not spend time with black people, but rather studies them from afar, generalizing them into a single subject so easy to comprehend that he claims to understand it perfectly (para. 37).

The colonel is not joyful because he is reunited with a beloved comrade, but because his servant’s return seems to prove that African-Americans love captivity. To celebrate that there is no reason to not reduce a human being into part of a cotton assembly line, “the colonel killed the fatted calf for Grandison….” (para. 120), immediately drawing a connection to the renowned tale of the prodigal son running back into the arms of his father. Only a week later, Chesnutt quickly subverts this by having Grandison run into the arms of Canada. Even better, given that Grandison and Betty are married, the runaway may soon become a genuinely good father himself. Perhaps he is already a surrogate one to the equally clever Tom. Similarly, Peele alludes to the verses Romans 12:1-2 in the opening of his film and sarcastically mimics the racists who would take it out of context. His cacozelia urges African Americans “...to present their bodies as a living sacrifice….” (Peele 2) for their white gods. He then takes this to the next level, creating an original leitmotif that also flips the dynamic between the oppressor and the oppressed on its head.

In Get Out, the irony of Chris's surname being taken from a president who is highly praised in the United States despite being a slaveholder is not lost here. George Washington has been immortalized into a national symbol that can be seen on the quarter coin, the one-dollar bill, and Rushmore despite his crimes. In stark contrast, much of Chris Washington’s development revolves around the symbol of the deer, which represents his feelings of helplessness surrounding the crime committed against his mother. A large part of why he feels responsible for her death is that he did not call the police when she went missing because he could not be certain if they would even investigate it.

Peele sharply juxtaposes this with some dialogue from Dean Armitage who quips, “...one down…a few hundred thousand to go” (20), going as far as to not only snicker about killing a deer in the same way Chris's mother was killed, but implying he looks forward to murdering more since there are too many anyway. The sentiment expressed by Dean embodies how the majority often trivializes the suffering of minorities because they perceive the latter as pests. On top of that, his attitude is reminiscent of the twisted entertainment many slave masters derived from publicly lynching slaves in the masses as well. This adds yet another layer to the deer, as it not only represents Chris's guilt but also the struggle of marginalized demographics to have their deep-seated systemic issues taken seriously by the institutions who inflicted that very trauma. As a result, when Chris breaks out of the sunken place and impales Dean with the antlers of his taxidermied deer head, it is immensely karmic. His apathy has gorily and gloriously stabbed him in the back.

Another excellent portrait of this apathy is the colonel, and his case has warped and worsened from mere indifference to total denial. Going back to the beginning of the story, the colonel attempts to assure himself of Grandison’s loyalty before letting him leave the south with his son Dick. He proclaims that the abolitionists in the north are “cold-blooded, heartless monsters…who would break up this blissful relationship….” (para. 52). Grandson seems to share his sentiments, pitying those who are freed, outright stating that he is proud to belong to someone (para. 51), and affirming his dependence on his owners even more by asking the colonel for permission to hit an abolitionist if he encountered one. Even better, Grandison emphasizes his helplessness by saying he would tell Dick and have his master punch them in the face instead (para. 56-58).

Of course, African-American readers know that Grandison is only playing the part to "pass" this test of loyalty, but the colonel, in his apophasis, has deluded himself into believing that his prisoner is genuinely grateful to him. This is when only a few seconds ago he threatened any “ungrateful niggers” with “the short shrift” (para. 35). He would not just penalize them, but execute them with such severity and suddenness that they would not even have time for a confession. The existence of a confession connotes the existence of a crime, but the only crime they have committed is fighting for their right to independence. Meanwhile, he is participating in enslavement, which is now considered an official crime against humanity. Hilariously, he then goes on to say that “...your young master will protect you. You need not fear when he is near'' (para. 59), claiming that he is protecting Grandison, when logically he is the one Grandison needs protecting from. He has no qualms about abusing and killing black people, but he sees himself as their savior. To him, a black adult is a naive newborn at best and a beast of burden that must be beaten into compliance at worst. This is eerily echoed in Thomas Jefferson’s statement to Edward Bancroft on January 26th, 1789: “To give liberty to, or rather, to abandon persons whose habits have been formed in slavery is like abandoning children” (Stanton 3).

The colonel’s hypocrisy does not end there. When his own slave goes missing he refuses to “blame Grandison so much as he did the abolitionists, who were undoubtedly at the bottom of it” (para. 104), seeing black people as so naturally inclined to submit to the white man that they must be manipulated into fighting for their liberty. The colonel’s relationship with Grandison is not paternal, but one of paternalization. His “kindly protection” (para. 52) only lasts as long as Grandison does not step out of the identities he has imposed upon both of them: the simple servant to his fatherly master. This psychological dimension of enslavement is expanded upon in Get Out, only this time from the perspective of the enslaved.

At the beginning of the film, the Armitages seem hospitable to Chris as well. As the scene progresses, Dean hugs Chris and insists that he call him by his first name, much like the colonel has a familiar and casual back and forth with Grandison. Dean also takes a lot of pride in his knowledge surrounding African-Americans, gushing over Jesse Owens’ win at the 1936 Olympics. On a surface level, Dean seems innocent enough when he praises Chris for “[knowing his] history” (24), but Dean’s surprised tone could very well indicate that he thinks he knows black culture better than black people themselves.

Whereas the colonel endears himself to Grandison by giving him tobacco to chew, Missy worries over Chris’s smoking habit. She even invites him to a free hypnotherapy session to treat his addiction. During the scene, she also seems to be helping him process, grieve, and heal from his mother’s death. However, her sympathies are quickly revealed to be a ruse to hypnotize Chris and send him to the sunken place.

Speaking of the sunken place, the director could be referencing the common practice of slave traders throwing their “cargo” overboard when they grew sick, injured, or the ship simply ran out of room. Peele is criticizing the objectification of black people to condone cruelty against them. This ideology is especially prevalent in Missy. The matriarch is no more worried about Chris’s health than the slave traders were worried about their diseased and wounded “property.” Her real concern is that his smoking habit could damage his lungs and make him harder to commodify for the pleasure of their wealthy friends.

The wealthy friends in question swoon and fawn over Chris' athleticism and artistic skill because of how it can serve them, not actual admiration and respect. Much like the colonel forces the role of a faithful slave onto Grandison, the Armitages diminish Chris into a vehicle for their superior white consciousness. The Armitage's modern-day “happy slaves” Georgina and Walter, who they insisted were part of the family (26), are in fact being used as hosts for their grandparents. Once again, their benevolence is merely a facade, and as soon as Chris escapes from those cerebral chains, they immediately try to give him short shrift as well.

Though the author of “The Passing of Grandison” and Get Out’s director were born nearly a century apart, the commentary shared between these two pieces of media indicates that for better or for worse, legends never die. The happy slave and the good master are far from dead, and far from fiction to many groups who would rather coddle their numbed conscience and bruised ego than confront the truth. Peele and Chesnutt humiliate the Jeffersons, colonels, and Armitages of today to terrific effect, but they do most of the embarrassment for themselves. Their true colors shine through in the bright reds and blues of the Confederate flags they wave in front of parliament as they lament the loss of the sovereignty that they denied to African-Americans only a few decades ago.

Works Cited:

Chesnutt, Charles Waddell. "The Passing of Grandison," The Wife of His Youth and Other Stories of the Colour Line and Selected Essays (1899), edited by ReadHowYouWant, 2008 edition.

Jordan Peele. Screenplay of Get Out. Script Slug, https://www.scriptslug.com /assets/scripts/get-out-2017.pdf

Rae, Noel. “How Christian Slaveholders Used the Bible to Justify Slavery.” Time Magazine. 23 February 2018. https://time.com/5171819/christianity-slavery-book-excerpt/

Springston, Rex. “Happy slaves? The peculiar story of three Virginia school textbooks.” Richmond Times. 14 April 2018. https://richmond.com/discover-richmond/ happy-slaves-the-peculiar-story-of-three-virginia-school-textbooks/article_47e79d49- eac8-575d-ac9d-1c6fce52328f.html

Stanton, Lucia C, and J. Jefferson Looney. "Those Who Labour for My Happiness". University of Virginia Press, 2012.

Walters, Shamar. "Scholastic Pulls Children's Book Criticized for Depiction of Happy Slaves." NBC News. 18 January 2016. https://www.nbcnews.com/news/us-news/scholastic-pulls-children-s-book-criticized-d epiction-happy-slaves-n498986

About the Creator

Phoebe Sunny Sheng

I'm a mad scientist - I mean, teen film critic and author who enjoys experimenting with multiple genres. If a vial of villains, a pinch of psychology, and a sprinkle of social commentary sound like your cup of tea, give me a shot.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.