Hartford Has "It"!

As I got older, I began to wonder: “How can I be on the same street, but in vastly different worlds?”

1: Where are you from?

It was not until I left home, that I realized what “home” truly meant to me as a Black American. As an undergraduate student, in the summer of 2018, I studied abroad in Ecuador. While there a handful of students and I participated in a social entrepreneurship program that aimed to help local indigenous communities establish and launch international business ventures for community development, social good, and general self-efficacy.

My time in Ecuador was entirely transformative. During my time there I stayed in two rural homes made of concrete and tin, and one posh urban mansion of a local university professor. I trekked with my cohort through the jungle, rode in the back of local taxi trucks, and for the first time in my twenty years of living, tried avocado (I know, late right? I’m totally hooked now).

I experienced breathtaking sunrises, bathed in a beautiful outdoor shower, and even ate guinea pig! Barely able to speak Spanish on my own, I pre-recorded my home-stay address in Spanish and showed the taxi drivers, to which they smiled and laughed, taking me to my homestay.

While there, the Ecuadorian locals were fascinated by my dark skin, long nappy locs, sharp almond eyes, and towering stature -- among them, standing at five foot seven -- I was nearly a giant. When I passed them, along with my peers, I often got the longest gazes. Of course, seeing White Americans travel abroad was nothing more than a demonstration of their historical power and freedom of movement, afforded to them by their ancestors' centuries deep conquest for global power and domination. I, however, served as a visual anomaly to this privileged American prototype, seeing that I was -- the fly in the buttermilk -- that challenged their perception of what an American was.

I remember them asking -- “De dónde eres” [where are you from]?

To which I responded in broken, Americanized Spanish: “Los Estados Unidos.”

This revelation solicited varied responses of bemusement, shock, and sometimes even reverence.

2: What does home mean?

Despite the sensational and riveting experience of being out of the country, the question -- where are you from -- inspired a deep-seated restlessness in me, to return home. I didn’t quite place the feeling as “homesickness” because I certainly wasn’t miserable. The feeling was more so a fond, reminiscent desire, for the familiar. Being totally inundated and reoriented into an entirely different hemisphere, language, and time zone became the least of my concerns.

My primary conflict of concern was my diametrically opposed understanding of what my desire for home meant. On the one hand, I longed for the familiarity of home, in the United States, but on the other hand, on a deeper and spiritual level, I felt that the United States was never truly home.

As a Black American, my historical legacy of being in this country is inextricably linked to the capture and forced migration of my ancestors. With this bitter reminder in mind, that I am an African, four hundred years removed from the motherland, calling the United States home provoked some level of repulsion and defeat; but in reality, this is the only home I’d ever known.

Thus, my first identity crisis was born.

3: In America, but not of America

As these feelings ruminated and percolated in my mind, I habitually listened to Diana Ross’s feature song “Soon as I Get Home” from the iconic African American film The Wiz.

[*please feel free to listen to the linked song, and if you haven’t already-- watch. the. movie! It is an American treasure, I promise you*]

This particular verse resonated with me …

There's a feeling here inside / That I cannot hide / And I know I've tried / But it's turning me around / I'm not sure that I'm aware / If I'm up or down / Or here or there / I need both feet on the ground / Maybe I'm just going crazy / Let myself get uptight / I'm acting just like a baby / But I'm gonna be / I'm gonna be alright / Soon as I get home

I was indeed turning around and turning away from my limited conception of what it meant to be African American. Of course, I knew that to be African American was to be “African without memory and American without privilege” but beyond that, I never thought about what it meant to experience and conceptualize home while outside of the boundaries of the United States.

The reality dawned upon me that I was in America, but not entirely of America and that I emerged from a group of people stripped of an identifiable nation, cultural flag of heritage, or language of our own.

However, I also realized that despite the historical trauma of erasure, Black American’s are habitual innovators. Even in light of our experiences, we created an internationally recognized and imitated flagship Black American cultural ethos of justice, resilience, and above all else, soul.

4: Emergent culture and the theoretical creation of “home” as a Black American

In some regards, it isn’t too far to posture that Black American culture is the conduit through which the United States has risen to global pop-culture ascendancy and influence. I would argue that it is the emergence of Black culture, born out of our trauma, trials, and triumphs, that makes the United States our theoretical home.

I mean think about it, on average I estimate that Black American culture saturates mainstream media in all forms, at about 75%. Sure, that is a generous estimate -- but when you go into Target and see juniors attire that says “Flex on ‘em,” or you go to an online website that features nonblack models with cornrows and jelled baby hairs, and you see internet culture proliferated with African American Vernacular English as standard communication; you begin to wonder what the end game of it all is.

Like, yeah, it’s lit that Black Americans continue to be the country’s inexhaustible reserve of entertainment, but what exactly are we getting from it? Most other ethnic groups get exclusive dominion to market off of and capitalize on their cultural heritage -- but Black Americans? Nah, we are just an accessible and consumable public good.

In light of the cultural capital Black Americans have contributed to the country, as well as a plethora of underpaid labor, emotional service, and endured abuse, we have little to show for it across the board in domains of quality of life; which to me is indicative of our sustained psychosocial subjugation.

What exactly do I mean by psychosocial subjugation? I mean that despite what Black Americans give we never experience the appropriate reciprocal balance of getting. Even to the extent of getting exclusive financial ownership over our creative capital and cultural contributions [e.g. Jack Daniels stolen recipe; e.g, Kentucky Fried Chicken stolen recipes, the list goes on]. Or even getting our fundamental human rights needs met, in a country where we made it the “land of the free” and fought for the abolition of its position as the “home of the slaves.”

This psychosocial subjugation is the compound express interest of the United States to siphon sociocultural capital off of Black Americans, while psychologically inundating us with anti-black social programming that we are not worthy of compensation for our contributions (ergo subjugation). That we are nothing more than an entertainment source. Statistically, across the nation, Black Americans lack access to quality: education, safe housing, food, water source, recreational equipment, and much more.

In contrast to the obvious demonstrations of what Black culture is or is perceived to be, people don't often ask: what exactly is “White culture”? How about trying these five words: exclusion, security, wealth, domination, and legacy.

People don’t often introspect on “White culture” or what it means, or how it is expressed or demonstrated, but my hometown of Hartford Connecticut taught me just exactly this. Through research, lived experience, and wisdom -- I would like to share with you all, the story of my hometown…

5: Welcome home: Hartford, CT!

Located in the northeastern corner of the United States, is Connecticut, the “constitution state.” Fun fact: Connecticut is the third smallest state in the United States, but the fourth-most densely populated state in the country!

My city is teeming with history! After the Civil War, “Hartford grew to be one of the most prosperous cities in the nation, and by the late-19th century, was the wealthiest city in the country” (ConnecticutHistory.org). To. We are also home to the country’s oldest public art museum, The Wadsworth Atheneum. Our iconic Bushnell park was designed by none other than Hartford-native, Frederick Law Olmsted (who then went on to design New York’s Central Park, might I add!).

I would be remiss to tell you that architecture is our thing. The architecture of the city is monumental and absolutely gorgeous. Mark Twain said of the city of Hartford in 1868, "of all the beautiful towns it has been my fortune to see this is the chief” (TwainQuotes.com). Beauty, creativity, and innovation compose the core essence embedded into the cultural fabric of our city. The Connecticut History organization notes about Hartford’s architectural legacy that “from parks created during the City Beautiful movement to modernist and post-modern skyscrapers that punctuate our skyline, the state’s architecture tells the story of a diverse and emergent society” (ConnecticutHistory.org).

Not to mention, almost every child that has passed the old Colt Armory warehouse at one point and time thought that it may have been the home of Disney character, Alladin. However, the star-spangled, onion-shaped, blue dome actually served as a key gun manufacturer for the nation during World Wars 1 and 2. Further, the Colt Armory and its productions contributed nationally to the Industrial Revolution! And now it serves as an eclectic, artsy, loft-style warehouse, apartment complex with starting studio rates of $1300 a month.

Ah, my beloved Nutmeg State! Also nicknamed “the land of steady habits” -- I can certainly tell you a few things about our habits, we love our Dunkin Donuts and “mixmaster” I-91 morning traffic jams, because we are guaranteed to show up every time. And right at the heart of our state, is our capital city, Hartford, the insurance capital of the world! The entire downtown of Hartford is a business district of insurance companies, with the largest one being Aetna, the, “largest colonial-style building in the world and the largest office building in Connecticut” (Singer 2017).

I mean honestly, not to toot our own horn but -- at our peak not only were we an economic powerhouse, and our ancestral “Hartford residents went on to invent the revolver, the pay telephone, the gas-pump counter, gold fillings, air-cooled airplane engines and the first American dictionary” talk about impact (Zielbauer, 2002)!

At one point we even had our own Chinatown too! Hartford at its peak was a central hub for innovation, culture, art, and above all else creative passion!

Hartford is also home to some of the greatest literary icons in American history, such as Mark Twain [e.g. “Huckleberry Finn”], Susan Collins [e.g. “The Hunger Games”], Harriet Beacher Stowe [“e.g. “Uncle Tom’s Cabin”], and Stephanie Meyers [e.g. “the Twilight Saga”] and someday in the future, maybe Hartford will proudly claim that they are home, to me.

However, even in spite of this historical legacy of greatness, there is another facet of Hartford, that makes it entirely American and entirely problematic. Like the fact that our insurance companies had an active historical role in the process of selling insurance policies for enslaved Africans. Not to mention, Mark Twain’s iconic novel, Huckleberry Finn, was about the juxtaposed journeys of the pursuit of freedom experienced by a free White youth, and an enslaved Black man. Or the fact that the business district was expanded at the expense of building the I84 and I91 freeway straight through African American neighborhoods in order to barricade the predominantly Black, Hartford North End, from the white-collar elite spaces of downtown.

If there were ever a city that was the concentrated, microcosmic reflection and embodiment of the fundamental American racial divide, it is Hartford, Connecticut.

As a child, my mother would bring my sister and me to the West Farms Mall in West Hartford to do our weekend shopping, eat hot pretzels, and get fresher, quality, groceries in the neighboring plazas. We would often take the street route by going down Farmington Ave.

Farmington Ave is a very long street that stretches from the downtown Hartford business district, to the wealthy, white suburbs in the mountains of Farmington.

When we would go down this street, it always blew my young mind that as we left the urban city neighborhoods, littered with garbage, dominated with corner-stores and fast food shops, minimal greenery, and the absence of any intentional beautification, the landscape would transform over the span of a few blocks.

Right when you get past the Dominos, the Hartford Fried Chicken (HFC) joint, the KFC, a Subway, and then the last fast-food chain on the “people of color end” of Farmington Ave, Burger King, you’ll come into the “white end” of Farmington Ave.

The “white end” of Farmington Ave, begins where the “nonwhite” Hartford poverty line ends. In an article in the local journal, the Connecticut Mirror, Mayor Justin Elicker stated that “Connecticut is one of the most racially segregated states in the country, both geographically and economically” (Elicker 2020).

Gradually, as we rode down the street, there would be less litter. Suddenly, there are no fast-food restaurants within the immediate vicinity of a bus line. The sidewalks are well maintained and well-lit. There are a handful of long-established mom-and-pop restaurants, stores, and shopping plazas that are well maintained. Not to mention that a decade ago, the town of West Hartford sanctioned the construction of their crowning jewel “mixed-used” development project, Blue Back Square, a high-end retail shopping center with residential living; in a posh and “new urban” environment [whatever that means].

West Hartford is actually home to various urbane, high-end, flossy, shopping centers that are within a ten-mile radius of each other. In addition to Blue Back Square, West Hartford also has “Corbin’s Corner” and “Bishops Corner” and these plazas are home to top-name retailers such as Saks off 5th, Crate and Barrel, Whole Foods, Trader Joe’s, Best Buy, and Target to name a few. The shopping centers are comfortable, there is plentiful access to trash bins, and there is scant a “fast food” chain in sight, but rather, healthier and more appealing “fast-casual” options such as Chipotle, Panera, and Noodles & Co; and of course, they also have restaurants with “$$$” ratings on Google to boot.

As I got older, I began to wonder: “How can I be on the same street, but in vastly different worlds?”

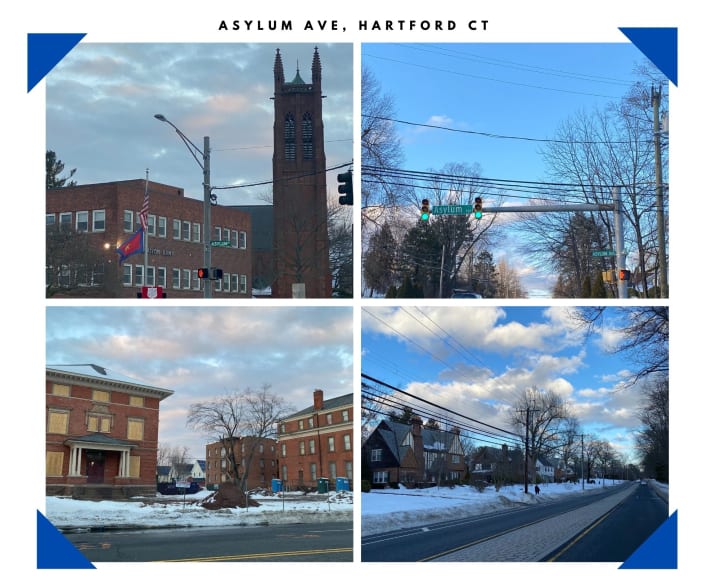

I realized that this phenomenon was not just isolated to Farmington Ave, but it was also in effect in our other major avenues, Albany Ave and Asylum Ave, as well.

All three of these avenues are anchored in the downtown Hartford business district, and snake their way through Black and Hispanic communities, before extending out to whiter, wealthier, areas.

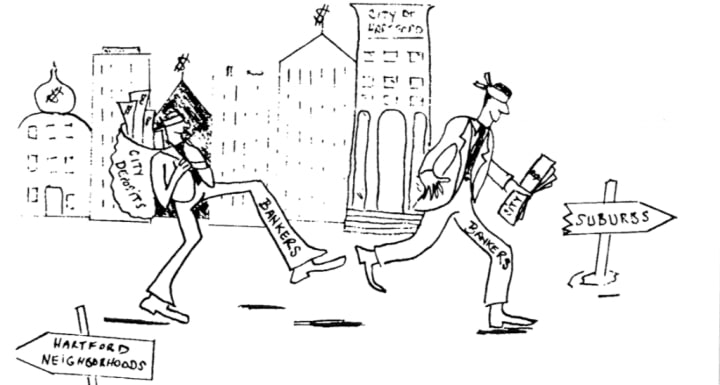

Unfortunately for the nonwhite residents of the City of Hartford, the downtown business district only serves as a central employment and opportunity hub for privileged suburbanites to establish their careers, make a living, and retire back to their racially homogenous communities at the end of the business day. These avenues that traverse through these blighted, impoverished neighborhoods are nothing more than byways for the white-collar class to get back to their own segregated neighborhoods.

At its peak in the 1960s, Hartford was a buzzing metropolitan area. A real urban center! We had the G Fox Building (the largest privately owned department store in the country at the time), The Gold Building, and the Travelers building, to name a few key features--and of course--the African American “Ancient Burial Ground'' housing the remains of our deceased ancestors from the 1800s.

At present, the downtown area which used to be a retail hotspot is nothing more than a large bus terminal and insurance district. Small businesses and retailers moved out of the city, crime increased in the neighboring Black and Brown areas, driving out white business owners to establish themselves in the spaces of Bishops and Corbins corners, and the downtown area suddenly fell under an unspoken 6pm curfew, wherein everything closes by dusk, and any manner of street life vanishes into the night.

Zielbaurer noted of the current state of the city in 2002, that,

Driving past the rows of abandoned buildings on South Main Street, just blocks from the gilded state Capitol, it is hard to remember that this city was once the envy of bankers, builders, artists and thinkers and the place of many universal firsts.

With such a promising history of economic opportunity and development, especially with our multitude of factory jobs and the insurance industry, it is hard to imagine that within the span of seventy years the city has taken a nosedive in all capacities of quality of life indicators. Our city is now charting for all the wrong reasons: the poverty rate in Hartford is 30.1%, one out of every 3.3 residents of Hartford lives in poverty; the 2019 crime rate in the city was 1.4 greater than the national average; and our urban school and educational outcomes are among the worse in the nation.

The story of my hometown is the microcosmic reflection and story of the American way of “White culture.” Remember those five words I mentioned earlier-- “exclusion, security, wealth, domination, and legacy” -- these values, taken together with action, have played an integral role in the present-day legacy of my hometown today and how it came to be.

6: Hartford Definitely Has “It”!

Recently in 2013, the city rolled out the vague rebranding catchphrase “Hartford Has It” to embody its city revival initiatives. But what exactly is it? And can it take into account and be interpreted to also include our systemic and structural race problem, which is made manifest by White culture in practice?

I do believe that the progenitors of the phrase intended for it to be broad enough to be applicable in various interpretations and capacities, and with this in mind, I will unpack what it entails in the context of White culture and its impact on the legacy of Harford’s ascendancy and unfortunate decline. So let us dive into our White culture toolbox and explore the various ways in which they are made manifest and expressed, and how inevitability it has made an indelible mark on the City of Hartford.

Exclusion

In a New York Times Article article written in 2002, titled “Poverty in the Land of Plenty: Can Hartford Ever Recover?” journalist Paul Zielbauer, explored Connecticut’s complicated state of affairs, highlighting the city's rise into financial notoriety, and nosedive into economic despair. Zielbauer notes that,

Hartford's descent reflects the central conundrum of Connecticut, which has the nation's highest per capita income but also has a split-level economy of affluent suburbs and almost universally floundering cities.

The dichotomy of economic disparity between the suburbs and cities came to be as a result of compounded issues of white flight, implicitly racist policies and government practices, the insulation of wealth, and the perpetuation of inequality all for the sake of maintaining the potency of de facto segregation.

In 2002, Myron Orfield, a Minnesota state representative at the time noted that “if urban distress amid suburban affluence is a national pattern, the pattern in Connecticut is magnified by the deeply held allegiance to ''home rule,” he continues that “each town's authority to zone, tax and enforce its policies without regional oversight” is the driving policy behind why wealthier towns are “insulated” from failing cities,

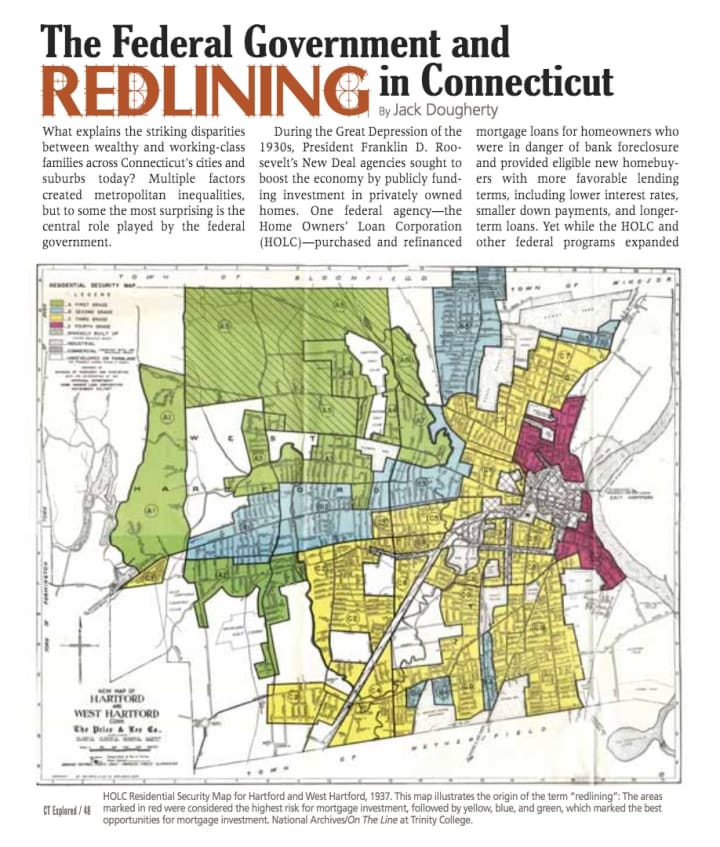

This is where the critical foundational element of exclusion comes into play. During the 1960s, as sanctioned by the Federal Housing Association, Connecticut implemented the housing policy known as redlining, wherein neighborhoods and districts were segregated based on an A-D quality metric grade. With A being “most desirable” and D being “least desirable” especially when “inharmonious racial elements” are taken into account. Certain neighborhoods also have covenants in place so that nonwhite families could not move in.

Simultaneously to compound the redlining phenomenon during the 1960s, the city also broke out into race riots, as the Great Migration from the south brought many African Americans from Alabama and Georgia [where my ancestors also hail from]. In 1965, the Black population had grown from 25% in 1965 to 75%, but trouble came with the contention of Whites owning 80% of the businesses, thus excluding Blacks and Hispanics from employment and economic opportunity (Fernandez 2018).

To further compound their racial exclusion, Blacks were also subjected to police brutality and marginalization. To combat this oppression the Black Panther party opened a chapter in Hartford, and the Black Caucus of the North End “led a march to protest housing conditions and neighborhood segregation, in response to the murder of a black youth by a police officer” however, they were interceded at the South End and met with 250 armored police officers (Fernandez, 2018).

The Black Caucus identified the only way to challenge white oppression was through insurrection and violence, and with these orders -- “Black youths fought against state and city police in the streets, damaging nearly one hundred buildings, including a public library and a North End supermarket” (Fernandez 2018). Sound familiar [think: Minneapolis riots]?

At the peak of the race riots and pushback came a critical mass, but not for the good, as the races vied for power over who would steer the future of the city. A closely-knit group of powerful businessmen known as the “Bishops” who were heads of the insurance companies came together and created a “secret plan” called the “Greater Hartford Process.” This plan “envisioned moving Hartford's blacks and Puerto Ricans out to newly purchased tracts in the rural suburbs” (Zielbauer 2002). However, when this plan leaked, it fanned the flames of contention and racial outrage, driving minorities into combat mode, and whites into defense.

Rev. Michael Galasso, a priest at St. Peter's Church on South Main Street at the time, shared that the aims of the plan were to “get the poor people out of the city and develop it into this island for the white power structure” (Zielbauer 2002). Talk about old-school gentrification!

With this plan leaked, the potency of animosity became too great to bear. Between the Blacks, Whites, and Hispanics, the chasm of difference became too great, and the only enforceable solution implemented by the financially empowered White class, was to divide, ergo de jure segregation. Thus, if White folks could not push minorities out of the city, they strategically maneuvered and practiced to keep them in -- by creating isolated, concentrated, urban pockets of minority city domains, and isolated suburban pockets of white domains [e.g. “white flight”].

Security

Separate, but artificially unequal, the state-sanctioned the implementation of policies that would secure the historical exclusionary chasm hatred created. In 2002, a democratic state representative at the time, Jefferson Davis, stated that ''what we've done in Connecticut is segregate Hartford so dramatically by class and race that it's no longer a viable economic unit” (Zielbauer 2002).

A long cry from its glory days, Hartford has become a financially crippled urban dwelling, home to nonwhite, poorer residents, who as a result, are exposed to higher levels of crime and poverty.

New Haven Mayor, Justin Elicker, stated in his article on Connecticut segregation that,

Black residents are overwhelmingly concentrated in our cities, where they pay the highest tax rates and send their children to the lowest-performing school districts. For our entire history, Black Americans have been deprived of resources at the hands of racist systems that have solidified deep, intergenerational poverty: from slavery to Jim Crow laws, then to redlining, disparate access to jobs, and the ability to vote. (Elicker 2020),

These security measures to maintain exclusion were taken over the span of many decades. After the practice of redlining, Connecticut began implementing school zoning districts that would also keep nonwhite residents out of well-funded, suburban schools.

Mayor Elicker (2020) expounds on the matter in his article, explaining that “unlike most states, property taxes fund almost all our local costs – particularly our schools. That means that towns with greater poverty must raise their taxes to extraordinary rates to cover basic services, and that vast educational inequities, even in neighboring towns, go unaddressed.”

In 2017 a Hartford Courant article came out stating that “In Hartford, A Few Blocks Can Make All The Difference For Children Growing Out Of Poverty.”

It is indeed true. Rebecca Lurye reports that “children who grew up in low-income homes in one section of Upper Albany — north of Albany Avenue and east of Woodland Street — went on to make an estimated $22,000 per year in household income. That's $5,000 less than adults who grew up in similar households on the other side of Albany Avenue” (Lurye 2018).

Remember what I said about being on the same street, but in different worlds?

Let’s look into the outcomes of low-income, predominantly White neighborhoods - “Low-income children from parts of Avon, Newtown, Stratford, Trumbull and West Hartford went on to report about $55,000 in household earnings” (Lurye 2018).

In typical American fashion, our race and economic status is often inextricably linked, unless we take the extraordinary or alternative measures to shatter and shake the statistics set in place, before our birth, to keep us locked in the cycle of being uneducated, disenfranchised, and poor.

Wealth

In 2020, Dan Smolnik reported in the CTMirror that “Connecticut has the highest level of income inequality in the country, with a Gini Index for the 2014-2018 period at .496, above even that of the country as a whole at .482” (Smolnik 2020). Connecticut’s well-documented wealth inequality gap also has a significant racial component as well, which is no different than the national structure of the American economy.

White communities, in Hartford, and nationally, then exercise their cultural practices of exclusionary security through their financial power and leverage, in order to give themselves a competitive edge in quality of life domains such as: education, employment, housing; as well as to ensure that they are given premiere and elite experiences, services, and quality of care.

Domination

Through practices of exclusion, security, and insulated access to financial resources and wealth, White culture promotes and permits the domination of quality of life services, creating an implicit racial caste system that is inextricably linked to class, educational outcomes, employment, and career trajectory outcomes, housing outcomes, as well as health outcomes. It has been documented that the zip code you are born into can be a very predictive indicator of the quality of your life. And as we have seen, both documented in Hartford and the nation abroad, that those in predominantly White neighborhoods are positioned to be at the pinnacle of the caste system just by virtue of where they are born.

Just up until last year, Hartford was a food desert, with no grocery store [whereas West Hartford has two Whole Foods within ten miles of each other]. Just up until 2016 our Martin Luther King middle school had to be evacuated because it was so unsafe that it was “basically hanging on with duct tape and bubble gum” (Lurye 2020). It wasn’t until 2018 that nearly 140 blighted buildings received the attention they desperately needed after years of neglect. Do you think these issues would be permitted to go unaddressed for this long in a White community?

You may ask yourself-- what exactly is the end game of dominating entire societies and manipulating all avenues of opportunities in order to protect and bolster one racial group? And what it all comes down to is legacy.

Legacy

A legacy is composed of many moving parts, such as heritage, traditions, values, a bequeathment of wealth and fortune, or some level of prestige, power, or position as an inheritance. What happened to and became of Hartford is a classic American demonstration of the United State’s original sin: racism. Racism is the inheritance and White culture is the beneficiary; these two elements, in the context of our present society, are inextricably linked.

So in short, the entire epic legacy of my hometown was abruptly cut short and deleteriously eviscerated, when it was challenged to share its glory with those who were nonwhite; because in our current nation those two realities are mutually exclusive. Apparently, you cannot have a successful, thriving White culture, in the presence of successful, nonwhite persons; because it violates the stipulations and contract of the inheritance of racism.

Word count not including the notes section: 4,825

p.s -- happy Black history month, xoxo! ❤ ;*

Notes …

Connecticut History. Architecture. Connecticut History.org.

https://connecticuthistory.org/topics-page/architecture/

Connecticut History. Hartford. Connecticut History.org.

https://connecticuthistory.org/towns-page/hartford/

Elicker, Justin. (16 July 2020). Let’s tax Connecticut’s segregation. CT Mirror. Retrieved from:

https://ctmirror.org/category/ct-viewpoints/lets-tax-segregation-justin-elicker/

Joas, Jennifer. (20 November 2020). New Grocery Store Opens in ‘Food Desert' in Hartford.

https://www.nbcconnecticut.com/news/local/new-grocery-store-opens-in-food-desert-in-hartford/2366845/

Lurye, Rebecca. (14 Sep 2020). Students return to Hartford’s Martin Luther King Jr. campus after $111 million renovation to overhaul neglected school. https://www.courant.com/community/hartford/hc-news-hartford-renovated-mlk-school-20200914-voyjo4qikffrreh7prk5qbuu4i-story.html

Lurye, Rebecca. (08 Oct 2018). Nearly 140 Blighted Properties Fixed In Hartford. The Hartford Courant.

https://www.courant.com/community/hartford/hc-news-hartford-blight-update-20181008-story.html

Fernandez, M. (2018, March 01) Hartford, Connecticut Riot (1969). Retrieved from https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/hartford-connecticut-riot-1969/

Singer, Stephen. (03 Dec 2017). Aetna’s 164-year History in Hartford. The Hartford Courant.

https://www.courant.com/news/connecticut/hc-biz-aetna-timeline-hartford-20171203-story.html

TwainQuotes. San Francisco Alta California, September 6, 1868.

http://www.twainquotes.com/18680906.html

Smolnik, Dan. (30 September 2020). Income inequality in Connecticut towns has a racial component. https://ctmirror.org/category/ct-viewpoints/income-inequality-in-connecticut-towns-has-a-racial-component-dan-smolnik/

Zielbauer, Paul. (26 August 2002). Poverty in a Land of Plenty: Can Hartford Ever Recover? The New York Times.

https://www.nytimes.com/2002/08/26/nyregion/poverty-in-a-land-of-plenty-can-hartford-ever-recover.html

About the Creator

Princess Tay-Arjana

Execute. Fail. Succeed.

"Clarity is a state of mind, freedom ain’t real, who sold you that lie? I ain’t buying that.”

- SZA.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.