"Only the marvelous is beautiful." --Andre Breton, Surrealist Manifesto (1924)

Eraserhead is the dawning of David Lynch's tumorous, nightmare voyage through the land of cinematic subconscious fear and invasion; I say it is a "haunted film"; its grainy ninety minutes or so, which drag on with the zombie-like gait of a somnambulist, seem to evoke a timeless era of American history that never, in point of fact, actually existed. It is a world that seems ripped from the post-war memories of Eisenhower baby boomers; yet, it hearkens back, because of its curious soundtrack mixture of hissing, churning industrial musique concrete (designed by the late Alan Splet), with the Roaring Twenties jazz of Fats Waller, to an even earlier era: an era of flappers, gunzels, Harlem Renaissance horn-blowers and, well ...Fats Waller, of course. Yet, that is still not quite right. The film emerges, full-bodied, from the recesses of a dream, coming to us as a coded vision from the maelstrom of the filmaker's own subconscious arena, wherein the sins of the past are given growth, naturalistic growth, to blossom and sicken like overripe worms, weeding through the representational rock-like prison of his creative soul.

The Man in the Planet

It is a film about expiation and sin; ghosts of the past, and the symbolic suicide of the future. In it, a man creates a world in which to punish himself, a world within a world, for unspecified evil; represented here, by the huge image of his head floating over a rock-like brain, suspended in space. Henry (the late Jack Nance, who, it is suspected, was murdered) gives birth from his mouth to a sperm-like creature, or something akin to an alien worm, which quickly floats away from him and falls into a black, inky pool of obsidian water; an image of fertilization. We are treated then to an image of a burned, nude man (actor Jack Fisk), sitting at a window inside a house within the rock-like, crust-like surface of the planet/rock/brain.

Before him, are a number of levers. We can hear, going by, the sounds of industry, or a train proceeding into the distance. It sounds like the rattle of iron and steel. He finally pulls the lever hard, letting loose an industrial roar, the sliding of the links of a chain, setting machinery for the motion that will bring life to Henry's grey world.

We next meet Henry, seemingly contemplating this vision of his own birth. Turning, walking away from us with his prominent and iconic hairdo, his short trousers and shabby suit, he is a surrealist, cartoon character, caught in a world of overpowering gloom; we hear the lonely, miserable wailing of a steam whistle as he traverses the murky, pitted ground toward a wall, toward inky pools of oil bleeding forth from clanking machinery, whose provenance and use is obscure because it is an outgrowth, naturally, of the agitation caused by Henry's incarnation in this symbolic, surrealist Hell.

He walks famously past a streaked building, replete with dark, cold, windows like rows of unforgiving, insect-like eyes. Henry is made to seem smaller and smaller, more hunched and vulnerable, more at odds with a world that is unforgiving and lonely and literally colorless. He's stepped in a puddle on his way, wetting his sock; a metaphor for his life.

Eventually coming home to the grim confines of his building, he enters the lobby, which seems to have been embalmed from some past waiting room or lounge in Hades; and enters the grim, confining and dangerous-seeming jaws of the elevator. Proceeding into his apartment, a mysterious woman, a raven-aired sultry neighbor (Judith Ann Roberts) in a dark robe, who seems, for David Lynch at least, to have been the forerunner of Blue Velvet's Dorothy Vallens, reveals that a "Girl named Mary called on the payphone. Says she's at her parents, and you're invited to dinner." This is said with the strange, flat affect of the mentally ill.

Henry responds with a worried look and barely a reply. He goes into his apartment, dries his sock on the radiator, and retrieves from his bureau drawer a ripped photograph of a rather plain blonde woman. He also casts what appears to be a pea in a pan of liquid which, for unspecified reasons, is placed in the drawer. We see that a mass of bizarre root-like material seems to be growing on top of the night stand.

"So, you just cut them up like regular chickens?"

Henry ventures out into Eraserhead's eternal night. The lonely piping of Fats Waller's "Messing About With the Blues" plays in the background, as he walks lonely, deserted tracks, to a small house that looks as if it is surrounded on all sides by abstract metal junk. A worried face, the face in Henry's torn photograph, peers anxiously from a dirty window. The noise of industry becomes deafening.

Henry approaches the back porch, almost warily. The young woman, "Mary X" (actress Charlotte Stewart, who became more well-known for appearing on the popular television program "Little House on the Prairie"), goes out onto the porch to greet him. "I didn't know if you wanted me to come or not," complains Henry. "You never come around anymore." Right away, we have the foreshadowing of what will be a troubled relationship.

Inside, (the house seems incongruous to the factory-like environment in which it rests), the living room scene plays out with Mrs. X (Jeanne Bates) presenting herself as a suspicious, scolding and harsh termagant, a woman who asks the question, "What DID you do?" ; and, right away, we realize this is a double entendre. Mary suspects that Mother KNOWS exactly what Henry has done; she begins to have some sort of emotional seizure, and Mother X viciously brushes her hair; this somehow bizarrely calms Mary, while Henry tries to explain he's a printer at "Lapelle's Factory." His position on the couch paints him as an unappealing and awkward lothario, his ungainly, small form seems to lack any sense of comfort at being present.

Bill X (Allan Joseph) then speaks up from the dining room. Standing behind a table, he explains that he's a plumber who has "put every pipe in this neighborhood. People think pipes grow in their homes, but they sure as Hell don't! look at my knees!"

The last is the most bizarre line until one takes into account the visual metaphors as coded symbols of Eraserhead's essential hidden meaning. Bill's legs are literally "crooked." Though he is seemingly a minor character, too, this author would argue that he is essentially the lynch pin of the entire film.

The kitchen is a tiny offshoot from the rest of the house. A rickety screen door seems to divide it from the night outside. To the left, the stove and counter, wherein first Mr. Bill X, and then Mrs. X come in (it is filmed at an angle that almost seems as if they are on surveillance), and prepare the meal. The scraping of forks over bowls and aluminum trays is accentuated, amplified until it is unpleasant.

Seated at the kitchen table is the cadaverous, yet seemingly alive grandmother, played by Jean Lange, (shades of Lynch's first student film, The Grandmother, from 1970), who might have been taken from a painting by Whistler. Comically, grotesquely, a bowl of salad is put into her lap, two forks in her inert hands, and Mrs. X then manipulates her arms to toss the salad. Afterward, she puts a cigarette into her mouth, lights it, and the woman puffs, proving to the viewer that she is even alive. But, is this humor? Is it somehow to be read as a part of the film's submerged code?

The next scene commences with the huge creak of a door, and the chiming of a cuckoo clock, which appears to be growing as much else in the film, organically, from the wall. Bill X explains:

"The girls have heard this before but... 14 years ago I had an operation on my left arm here. The doctors said that I wouldn't be able to ever use it. But what the hell do they know, I said. So I rubbed it for a half-hour every day. And slowly I could move it a little, and use it to turn a faucet... and pretty soon I had my arm back again. And now, I can't feel a damn thing in it. All numb! I'm afraid to cut it, you know? Mary usually does the carving, but maybe tonight, you'll do it Henry..."

After this bizarre confession, one of the small "man-made" chickens is placed on Henry's plate. Since they are small enough for each diner to eat one singly, having Henry "do the carving" that "Mary usually does," is a coded phrase, a dream-symbolic way of speaking of the sexual menstruation of Mary; and then the transference of the sexual virginity of Mary to the possession of Henry, who has seemingly stolen it because of the revelation that is coming.

The reference to Bill's arm is obviously sexual and power-related as well, full of darkly humorous double meanings. The chicken, which comes alive and begins to move and squeal and bleed, is a play on the idea of a virginal, or even child-like young woman, robbed of her innocence by becoming sexually experienced.

Mrs. X reacts in another of the curious, spasmodic, near-orgasmic "spells" that Mary has first exhibited; it is as if the "normal" behavior of these women is simply a programmed mask, wherein certain subliminal cues can bring forth such intense feelings of fear and revulsion to render them on the verge of insensible hysteria.

Mrs. X flees the dining room, before coming back and telling Henry she wants a word with him. Getting him off alone, she tries to molest him in a weird, vampire-like fashion, before demanding to know if "You and Mary have had sexual intercourse? Did you?" At first, Henry balks at admitting it. Then, Mary entering (her image separated from the two by a long black pipe snaking through the screen), Henry is informed that "There's a baby. It's at the hospital. And you're the father!"

Mary, protesting that, "They're still not sure it is a baby!" is told by her irate, bloodsucking mother that"It's premature, but there's a baby." Further, she informs Henry that he's going to marry Mary, upon which he gets a nosebleed. This seems to fascinate Mrs. X.

Mary, still trapped behind the bent arm of the ubiquitous pipe growing through the seemingly false facade of their dislocating home, cries, asking Henry, "You don't mind, do you Henry? I mean about getting married?"

Henry, as if in an awkward, dream-like realization he must maintain appearances, answers apologetically, "No." Thus ends Act 1.

"All I need is a decent night's sleep!"

We next cut to Mary, attempting in frustration to feed baby formula to the monstrous, bandage-wrapped, fetal-headed freak that she has given "birth" to. It coughs, hacks, spits up the food, and she flings the spoon away in disgust. The scene itself is stark: a table, a single chair, and a window looking directly out into a brick wall.

Henry comes home, enters, lies down on the bed with his new family, gets a dreamy expression as he stares at the little glowing center in the radiator. It looks, to him, increasingly like another of the little "worlds," the subconscious, dream-world "Russian Dolls" that fit, one inside of another; Henry's world is entered through a hole in a planet-like brain, remember. The Baby, which is obviously not even remotely human, cries incessantly. The Baby, as author Ray Wolfe wrote in his excellent Online Guide to Eraserhead website, decades ago, is the living embodiment of Henry's unspecified "sin." But, it is not, truly, his own sin to bear. It is instead the transference of another man's grave misdeed, with which Eraserhead is trying, through coded signal, to inform us.

One coded image we have not yet discussed, one almost "dead giveaway" to the attentive viewer, is the scene wherein Mary, peering uneasily through the dining room door, weeping, is seen just over the top of her stupidly smiling father Bill's bald head--almost as if, like Pallas Athena, she were being given birth herself out of his skull. His monstrously idiotic grin, the position of her head, and the fact that she is weeping can all be read as a glaringly apparent hidden message. But, of what? If the reader has not guessed, by now, he or she may never do so.

Eraserhead proceeds slowly and inexorably forward, a dream now of frustrated nighttime oppression and nightmare. Mary, unable to sleep because of the hideous, mewling monstrosity on the tabletop, erupts, claims she's going home for the night, and, in a visual allegory of imprisonment, is seen reaching under the marriage bed for her suitcase. She tugs and tugs, her arm hidden from view, while holding on to the prison-like bars at the foot of the bed, her face just barely visible. This is a dream metaphor of imprisonment, and one of the film's most famous images. "All I need is a decent night's sleep!" she bewails before storming out. Henry answers, "Well, why don't you just stay home?"

She does for a short amount of time. In the interim, Henry, on "vacation," goes to his mailbox expecting the vacation pay that never comes. Instead, he seemingly digs in the symbolic dark, vacant box to retrieve a little worm. This is then put in a little cabinet, wherein it animates, illuminated in a circle of light, before going to and fro and burrowing into the great brain-planet floating in space. It then emerges, one end opening up into a massive, worm-like mouth that seems to presage Lynch's later Dune.

The camera zooms into the mouth; it is yet another opening, another entryway into the Eraserhead world. Holes in the roof of the tiny house wherein the Man in the Planet dwells, and holes in the planet itself; the entryway of emerging pipes, of the mouths of worms; Eraserhead is like a reality of China dolls, relativity reigning as everything can be reduced to a peep into a smaller and darker realm. It is in the giant, floating Head of Henry, it seems, wherein all resides.

The worms, or spermatozoa, or the thick tentacles of remorseless decay erupt from Mary, who has seemingly come back to loll in bed, rubbing one eye suggestively, and gesticulating beneath sheets that sound as if they are made of rubber. Henry, aghast, or dreaming, pulls the foul strings of corruption from her flailing form, flinging them frantically to and fro, till they splatter against the wall.

The Lady in the Radiator

The Baby is sick. It breaks out into little, spike-like tumors. Henry seems surprised that the baby, such as it is, has not simply been "faking" all along. More and more, his internal visions seems drawn to the little lighted space in the radiator, wherein he imagines a checkerboard stage of sorts, and a woman in Doll-like attire with tremendous, grotesque tumors or growths on her cheeks (The Lady in the Radiator, played by Laurel Near). She dances for him, back and forth, while, from a above, the sperm-worms fall to the stage. She crushes them, loudly, beneath her white heels, her face a comic-grotesque mask of delicate, coy smiles, her hands folded under her chin. She vanishes like the rest of his visions.

The most famous scene in the film, wherein the title is actually taken, is so intensely gothic and utterly, nightmarish and disturbing that it has the sense of a dream or vision the viewer will have seen before, or experienced on some visceral, psychic level.

Henry, standing overlooking the stage, backs into what seems to be a sort of theater balcony. His hands grip a rail (another pipe or cylinder), nervously turning or playing upon the smooth surface. A prop tree, placed on a mound of square earth, is literally wheeled out.

As Henry nervously looks down, it begins to bleed. His head then is thrust, with a loud pop, from his body, by yet another emerging, growing cylindrical pipe. It lands in the center of the checkerboard floor, in a growing pool of slick blood. It is a perfect image, but not quite the film's iconic one. That comes a few scenes later.

The head of the Baby is then seen to grow, serpent-like, from Henry's neck, emitting its same weird, piping, ghostly, tinny, torturous wail.

The head plops through the floor, falling to the filthy pavement outdoors. A homeless man (John Monez) lying on his back in the alley, reaches forth in desperation, while a young raggamuffin (Thomas Coulson) out of Dickens rushes forth and claims the bloody, severed head (whose scalp seems to be falling off), running away with it.

He takes it to a strange shop, wherein two renegades from Kafka (one a desk man with a buzzer, the other his huge, bearded, oafish boss), rule over the production of Number 2 pencils. The desk man (wearing a jacket and bow tie, and played by Darwin Joston), buzzes the Boss (Paul Moran), who comes out angrily and, poking a finger in the clerk's face, shouts "Okay PAUL!" However, upon seeing the boy with the severed head, he becomes friendlier and more congenial.

"Well sonny, what have you got there?" he asks. He takes the boy in the back, where a man (Hal Landon, Jr.) is sitting at a pencil-making machine. Using an obscure tool to saw off a sample of flesh from Henry's head, it is loaded into the machine. Presumably, because the workman writes and erases something, and then turns, telling them, "It's okay," Henry's flesh has been turned into pencil-top erasers. (Seen coming down a conveyor, row after row. Thus, an "eraser's head.")

In Heaven

The man blows pencil dust into the void. Henry awakens, and the last of the subplots (if Eraserhead can even be said to be possessed of such) unfolds, as the sultry, Dorothy Vallens-like neighbor across the hall approaches Henry (seemingly during one of the rare moments when he is NOT hallucinating), and says she "has locked herself out" of her apartment.

"And it's so late," she intones.

Then, of course, "Can I spend the night here?"

Henry and the woman make love, dissolving into a milky, murky pool of white liquid in the center of Henry's bed. Only her hair is, at least, seen floating above the surface. When they awaken, the woman is cruelly sickened and disturbed by the Baby, and Henry becomes ashamed. We take it she deserts him.

As if to confirm this, we then see Henry emerge from the darkness and look across the hall. The neighbor woman he has betrayed his wife with (but she left him, no?) is now laughing with a roly-poly little fellow credited in the titles as "Mr. Roundheels" (Raymond Walsh). They are laughing, seemingly at Henry, and the whorish woman, we see, sees the head of the Baby on Henry's neck, just as in his vision.

Humiliated and disgusted with his macabre life, Henry grasps a pair of shears. He approaches the Baby; which never ceases to cry, but here, seems almost to chuckle at Henry's distress. His "sin," thus, mocks him. He slowly, murderously, begins to cut open the bandages holding the baby's "body" together. A weird, bloody, vagina-like interior is exposed.

In a fit of homicidal sadism, he stabs the gory cunt-like inner workings, releasing a well of what looks like shaving cream. The Baby's head begins to elongate on its neck, finally severing itself, while sparks (energy, God, the "divine spark") shoots forth from the wall socket.

The giant Baby Head flies about, tormenting Henry. Behind him, he hears the sudden roar of the radiator, the explosion of the planet/brain floating in space. Huge chunks begin to be blown out of it. Henry now KNOWS what to do.

He envisions the iconic scene, his head floating in a cloud of pencil-dust. He must become the "Eraserhead." He must destroy the world he has created, his personal Hell; he must expiate his "sin."

The image of the bleeding tree is so significant--one of salvation, crucifixion; a Christ-like metaphor. The Lady in the Radiator, who has assured him that, "In Heaven, everything is fine...you got your good things, and I've got mine!"; she beckons to him in the light, the flame; to come, be extinguished. He goes to her, embraces her, embraces his own end. It is the culmination and finale of his seemingly interminable nightmare. Erased.

Stop the World

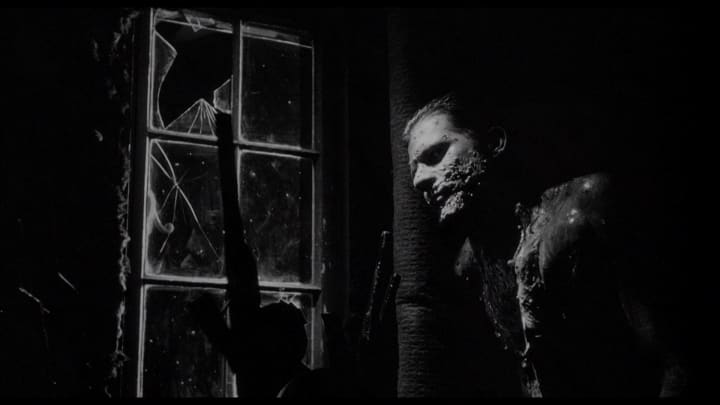

The scarred visage of the Man in the Planet (Jack Fisk) is seen pulling back the lever, burned by the sparks erupting from it. We see his burned flesh, his illuminated jaw, as we see Henry recline in the seeming universal light of death. Henry has paid for his "sin."

But, what, specifically, WAS Henry's sin?

This author would argue that the hidden subtext of Eraserhead, the coded message of the macabre dream, is that it was, in point of fact, NOT Henry's sin to have had sex with Mary. The Baby was never Henry's to begin with. It was simply conveniently fobbed off onto him.

"Mary usually does the carving, but perhaps tonight, you'll do it Henry. Alright by you?" Bill X asks, making hidden reference to menstruation. The chicken is "man-made," another coded reference to "being made," or perhaps, "turned-out"; a reference to sex and even rape.

Bill was afraid to "cut it." The entire dinner scene is a sexual horror fantasy, suggestive of vampire-like lust (Mrs. X), menstruation, and, finally, the black heart and soul of Eraserhead's sexual metaphor: incest.

Mary is a victim of incest.

Her father, Bill X., is the perpetrator. The mother, Mrs. X, conspires to disguise her husband's guilt, transferring it to Henry instead. Naively, Henry accepts this burden; his nose bleeds. Blood and guilt and sin and expiation are all related in the Christian narrative. The "Tree on Wheels" is a nod at same, as it also bleeds; the fact that it is obviously a prop may or may not be intentional satire.

The most telling scene, in which the weeping Mary seems to literally grow from the head of her own father (framed as she is in the doorway), while he moronically, mockingly grins in satisfaction, is the central visual clue unraveling the secrets of Henry's dark, distorted dream. Not Henry's rape, but Bill's, has created that punishing inferno of dark and malevolent shadow and putrefying time.

Haunted With Henry

I first saw Eraserhead in 1997, twenty years after its release. By that point, Jack Nance had already died. Ironically, the "Twin Peaks" actor reportedly met his death walking home from, of all things, a doughnut shop; reportedly he was accosted by two males, one of which assaulted the elderly man. He later died of a brain injury. The men were never apprehended.

Twin Peaks, of course, made use of donuts as a kitsch plot device. Art imitates life. Or, in the case of Nance, his tragi-comic ironic death seems to be the only fitting capstone on the man who will always primarily be remembered as the fantastically-coiffed and intensely strange Henry Spencer. (The name, incidentally, is ALSO known to history as that of a murderer from the early Twenties, who went to the gallows with a profession of new-found religious faith, but turned "chicken" at the very end. Or, so it is claimed by none other than Ben Hecht.)

The first four of Lynch's films, Eraserhead (1977), The Elephant Man (1980), Dune (1984), and Blue Velvet (1986), despite whatever individual flaws they may have had, or their reception by critics and audiences of the era, mark him out in his early years as a Hollywood "Wunderkind," a man (as Sartre said of Genet), "rotten with genius." Alas, I am NOT a fan of most of his later work, and I somewhat dislike his "Twin Peaks" (1990-91), as it brings to mind something J.G. Ballard once said about, "A forced, affected surrealism that is...horrible." In such a television format, a program like that is expected, out of necessity to retain viewership, to "up the ante" of weirdness every week, if for no other reason than "That's what the audience wants!"

(Whether that's true or not, "Twin Peaks" certainly didn't last long, its initial vision worn so threadbare and grown so distant from what made it initially successful, audiences soon lost interest. Except, of course, for the cult-like fan base that will adore and praise anything made by David Lynch, anything at all.)

Coming back to 1997, it was a "Quad Bash" festival on the Ball State University campus, in Muncie, Indiana, where I first, through the aegis of my old friend Buff, a cult movie fanatic, saw a grainy, third-generation bootleg of Eraserhead in a house full of drunk hippies.

Earlier, Buff, I and a young lady all had gone walking through the university "Village," very drunk ourselves, and amid milling throngs of drunk, incoming freshman. I remember drinking blood at some point in the evening, but this is all very vague.

At any rate, speaking of blood, in the North Quadrangle, the university had set out a huge projection TV, and were screening the then-popular movie Scream (1996), directed by the late Wes Craven, whose Nightmare on Elm Street (1984) I will soon be writing about. (I have already penned an essay on Craven's seminal shocker, Last House on the Left (1973)).

Superficially, the two films are often lumped together as "horror films"; they are stylistically and substantiatively light years apart. It seems fitting, somehow, that I should view both on the same evening. (Almost a surreal juxtaposition, in and of itself.)

We soon returned to the House of the Drunken Hippies, and, in the wee hours of the morning, when the scene in the living room looked as if it were a crime scene photo of a number of rapidly-cooling cadavers, I sat down very, very close to the television screen; and I watched, Eraserhead.

I was delivered into that dark, haunted world, my eyes peering beyond Henry into the hallways and dark crevices and corners, and shadowed halls; the film is less a ghost story than an actual ghost. After years of haunting video stores and even mail-order catalogs searching in vain for it, here it was, the phantom revealed.

Buff angrily came out at an ungodly hour, wrapped only in a bath towel. He turned the television set down ( I suppose it was blaring somewhat) before storming back to his room. He never acknowledged me, and I continued to sit there, enraptured by a very dark and troubling cinematic excursion; a prisoner, now, in an otherworldly dimension of the mind.

Eraserhead is said to have been filmed, partially, at Greystone Mansion in Los Angeles; which I take it is owned by the American Film Institute, which Lynch attended. It was donated by a wealthy industrialist, Mr. Doheny, and a murder also reportedly happened there. Perfect. Violent death, tragedy, timeless old ghosts wailing through the set of Eraserhead, filming the nightmare in the middle of the night; zombies of the subconscious.

It is said that Jack Nance encountered the ghost of Mr. Doheny on the stairway, one dark, lonely night. They did not specify which stairway, of course; but, I assure you, it's all true. Every word of it.

It's perfect. Eraserhead is not a movie; it's a paranormal phenomena. It's a haunting. It's a look into dire dimensions of black. It's the dying-infant wail of lonely, steam-whistle ghosts, at three A.M. It's the feeling in a dark and empty old room, an ancient tottering building from generations ago, that eyes are watching you. It is the tired, spent energy of the lonely and damned dead. Eraserhead is a haunted film.

(As I already stated, the name "Henry Spencer" originally belonged to an obscure American murderer. Maybe Lynch knew that. I hope he didn't. It's wonderful, cosmic irony.)

Finally, musician Peter Ivers, who composed the Lady in the Radiator's song, "In Heaven," was also murdered. Bludgeoned in his studio loft apartment, by another unidentified assailant, with a hammer. It was 1983. A curse, perhaps? The other actors, of course, do not seem to have faired so harshly by the hand of fate. The irony of his most famous song is not lost on those who know of his story.

Irony.

"In Heaven, everything is fine...", eh?

No.

(And in parting, let me reiterate, Eraserhead, and that era, and those old buildings from the era of flappers and gunzels, Prohibition and "Little Chicago" that I discovered in Muncie, Indiana in the six years that I lived there, still haunt me dually; twin phantoms from the twilight zone of nonlinear TIME.)

In Heaven, we are haunted. And on Earth, we dream.

Suggested Reading and Viewing

Wolfe, Ray. Online Guide to Eraserhead. The City of Absurdity: The Mysterious World of David Lynch. 1995-1997. http://www.thecityofabsurdity.com/papers/wolfe.html

I Don't Know Jack. Dir. Chris Leavens. Davidlynch.com, 2002. Film.

Eraserhead (1977) Trailer

About the Creator

Tom Baker

Author of Haunted Indianapolis, Indiana Ghost Folklore, Midwest Maniacs, Midwest UFOs and Beyond, Scary Urban Legends, 50 Famous Fables and Folk Tales, and Notorious Crimes of the Upper Midwest.: http://tombakerbooks.weebly.com

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.