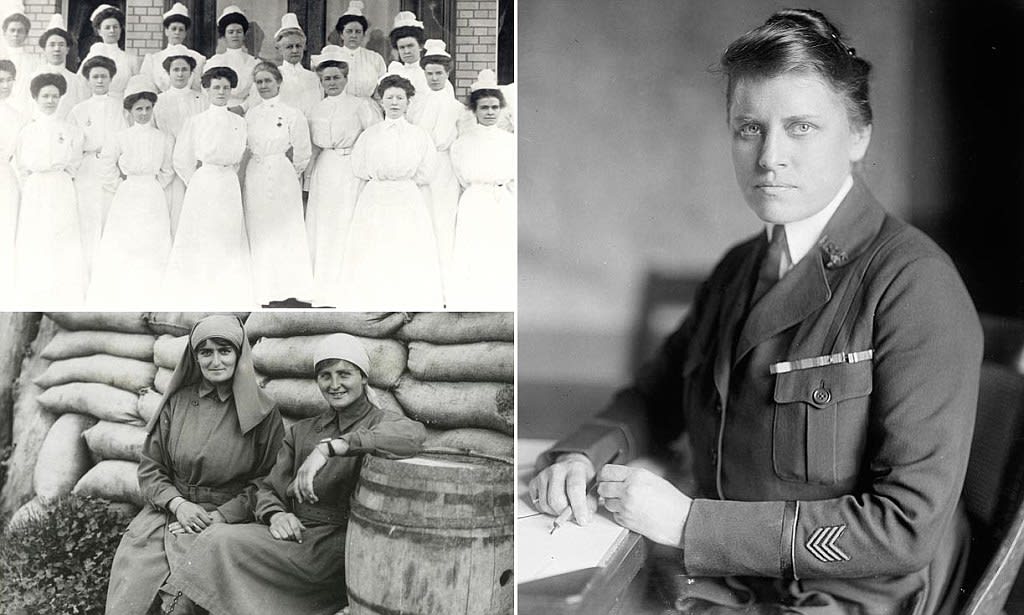

The VAD Nurses

Who Served During The First World War

Voluntary Aid Detachments or VADs were the voluntary nurses who wanted to give their time to care for the wounded soldiers during the First World War.

These VAD members were not entrusted to do ‘trained nurses’ work’ unless it was an emergency and there was no other option. When World War One started, these VADs were known to have ‘fluttered the dovecotes of professional nursing’ because of their enthusiasm to nurse the wounded soldiers.

This section of ‘nursing’ was initially introduced to support the military and naval medical services during ‘times of war’. However, it wasn’t long before everyone realised the very important role that these ‘nurses’ played in caring for the thousands of wounded soldiers during the First World War.

When World War One started in 1914, right through to when it ended in November 1918, trained nurses were sent abroad (at very short notice) under the banner of the Red Cross. Over 2,000 women offered their services in 1914, and from this ‘list’, individuals were sent (in teams) to areas of hostility such as France, Belgium, Serbia and Gallipoli. “From 1915 onwards they were joined by partially trained nurses (all women) from the VADs who were posted to undertake less technical duties”. (Nursing during the First World War).

These nurses had no idea what they would be facing or of the horrors of war, however, their sheer determination has been recorded in the pages of history, never to be forgotten.

The “Rules” for these VADs were extremely strict, but when we think about where they were being sent and what they were going into, these rules served as a protection and were of the biggest help. For example:

# No VAD member should question what work she does for the sick or wounded, whether soldier, sailor or civilian.

# A good knowledge of French was desirable for foreign service.

# All nurses had to be equally willing to work day or night, either at home or abroad.

# Where health certificates and references were ‘satisfactory’, the women were put on lists for home or foreign service.

First aid training was given, along with home nursing and hygiene by the approved medical people. Also, classes were given in cookery. Practice was allowed in actual hospital wards and in an infirmary. For those who were ‘talented’, training was given as a masseuse or in being to use an x-ray machine. This applied to the women mainly as the men who volunteered had their ‘own’ training.

Once they had passed the necessary exams (the fee to be examined was 1s 6d for evening candidates / 2s for day candidates), and received the first aid certificates and nursing certificates, these volunteers worked at a hospital for a month’s trial. When (and if) they passed this trial, the VADs were accepted into another hospital for three months’ “hard work” before being accepted full-time. Interestingly, these women were given self-defence classes and lifeguard training, for those who worked in the hospitals that were near water.

A sub-committee recommended a standard uniform for VADs, which would have “regard to economy, utility and the practical duties the Red Cross detachment would be required to perform on mobilisation”.

In February, 1915, a new system of “Special Service” was introduced. This would introduce a supply of nursing members to the Military Royal Army Medical Corps (RAMC) hospitals, which had previously been staffed by army nurses and orderlies from the RAMC. These ‘nursing members’ were qualified nurses and VADs.

VADs were also required to work in a “general service” section. What was this? When the men went off to fight in the First World War, VADs replaced them working in civic positions such as dispensers, clerks, cooks and storekeepers (back home). For those who didn’t feel that they could go abroad nursing, this was a way of supporting the War Effort — ‘doing their bit’.

“Rest Stations” were a major contribution that was organised and manned by the VADs. These volunteers provided food and other supplies for the soldiers who arrived by ambulance train, whilst waiting to be taken to the local hospitals, or who were travelling onto another destination.

Many nurses and VADs received the Red Cross medal, most of them having served between 4th August 1914 and 31st December 1919. Some 41,000 members received the award.

By the end of the First World War, 90,000 VADs had been mobilised to work at home and abroad.

The courage of these VADs shone through, as volunteers from every social class joined up. Some were great ladies who had never even washed up a dirty dish, coming ‘straight’ from the Edwardian drawing room. Others were secretaries, house maids and kitchen maids. Going from the “Golden Age” of the peaceful Edwardian period into the horrors of the First World War, these women all had one thing in common — the desire to help the wounded soldiers, at home and abroad, doing their part for their country.

About the Creator

Ruth Elizabeth Stiff

I love all things Earthy and Self-Help

History is one of my favourite subjects and I love to write short fiction

Research is so interesting for me too

Enjoyed the story? Support the Creator.

Subscribe for free to receive all their stories in your feed. You could also pledge your support or give them a one-off tip, letting them know you appreciate their work.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.