The Soil Reader

I do me job and I do it well ...

The King stares at me. All them in the palace do, every time. Well, not Geoff. Geoff makes me turn away. I appreciate that about the royal scribe. But these divine rule types, crowned in holy purpose, look right at me. Mind you, I don’t dare make eye contact. Not ever. I don't need to see to know. I can feel their gazes boring into me, full of judgment and distaste. They stare to remind me of me place in this world. Don’t look up, wretch. Don’t look up. But because of me place in this world, what do I know from Kings and queens and dukes and them others? Could be they're just thick-headed, dim-witted, the touched children of sibling lovers. Don't think much about it. I do me job and I do it well, just like Da before me. Da served the Irish Kings and they were a rough lot. Ate a lot of mutton, I suspect. Mutton don’t come out well. Digests fine, but the slurry it produces is putrid.

The King grunts, still staring at me. I feel the urge to say something. Irish defiance, as me Da calls it, swelling inside me.

Do the work, boy-o, I say to meself. Do da work ‘cause it’s important work.

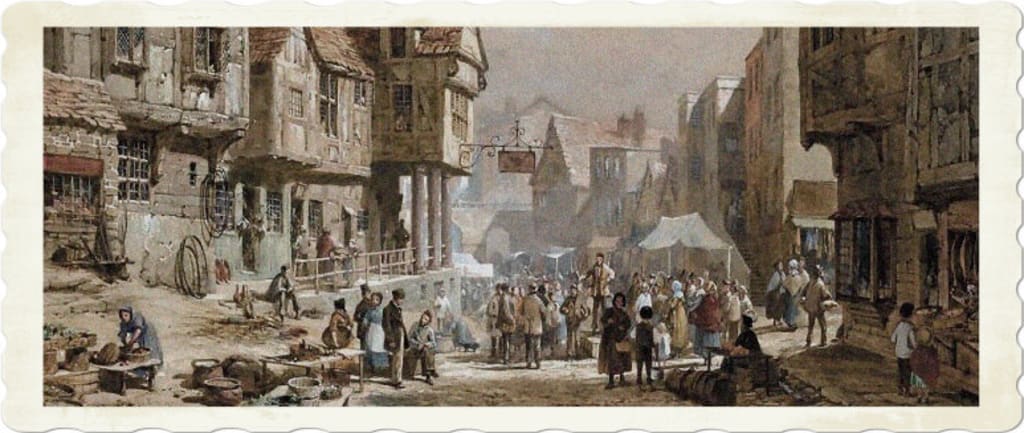

Is it, though? Am I a necessary contraption? Seems a monkey could do me job. Seen a monkey once, brought over to Cheapside by a fella with skin like a walnut. Brown with craggy lines etched into his cheeks. Geoff told me it’s called scarification and they do it as a ritual. I didn’t never work for that fella. Ate mostly dates and prunes, he did. Probably disposed to healthy movements, a diet like that. Ain’t the case with the King and Kin. Our great Highness, a hand of God though he is, ain’t what you would call regular. Eats mostly meat. Fact is, I don’t think a fruit or vegetable has ever crossed his Heaven-blessed lips. I wonder how many people that mouth has put to death, how many plots have spilled from that fat throat, how many blasphemous assertions of God’s will have departed his tongue.

The King grunts and there is a resounding plop. It sounds kingly. A royal, divine plop. Lots of people think me job only begins when their job ends, metaphorically speaking. Geoff told me that word, metaphorically. Even told me the meaning. I think that’s how you use it.

I don’t have schooling. Naught written in me life. Can read some. Geoff, he’s teaching me how to read better. Also teaching me how to be a proper man, as he calls it.

No, the job don’t begin at the end. It begins when the trousers drop. Have to listen. Have to smell.

There’s something wrong inside the King, I tell you. His movements are always accompanied by roiling thunderclaps and dead fish smells.

The King says, “Done.”

I say, “You sure, majesty?”

He says, “The King knows when the King has fully evacuated.”

What makes you different from every other sod, I think. Been a few times I’ve cinched up me trousers only to have to drop them again. A servant skitters from behind a curtain and retrieves the royal pot, plunks it in front of me with a loud clang and a splash. Disappears faster than a shadow at dusk.

King doesn’t like to see the servants, likes to think everything comes by the power of his royal will. If all them servants disappeared one day, as sure they might, with plague creeping across the cart roads, I wonder what he would do. Probably just wither up and die; unfed, unbathed, unclothed, his jewels falling from his fingers as he wasted away. I wonder what he would think at the end. All that power, all that control, only to die in unadorned desolation. I’m starting to think like Geoff talks. Must mean all them lessons are sinking in. Don’t matter none. Won’t never help me exceed me place. Once you’re in night soil, the stink of it follows you right into death.

I take out me soil stick and poke about in the royal expulsion. Not fully formed, but not watery either. Like a clot of mud. Bit of orange in there. A piece of carrot. The King is prone to lientery, so seeing a solid chunk of food isn’t unusual. But a carrot? He must have accidentally eaten a garnish.

Blood. Thin and light. From the out, not the in. Blood from the in is dark, thick. You can barely tell it apart from the rest of the soil. Color is mostly yellow-green, close to grey. Too much meat and barley bread, methinks. Maybe too much choler. Would explain the raised taxes and increased public executions. Seen a wife and her husband do the Tyburn jig just last week. Thinking about it turns something in me. Normal day, I would do me job, report to the court physician, and leave. Today, though, today is different.

“Pardon, your grace,” I say. “A question, sire.”

With a heavy sigh, he says, “Speak if you must.”

He don’t like it when people address him directly. Don’t like much, this one. Ain’t never happy. Ain’t never kind. They call him the Tyrant for a reason.

“Thank you, highness,” I say.

I don’t dare look at him directly, but when I raise me head to ask me question, I get a good view between his legs. While I do see his royal door knocker, that’s not what grabs me attention. There’s a servant girl underneath the King cleaning the divine fundament. Reminds me of a maid milking a cow. Our sight meets and her green eyes send a bolt through me soul.

Gwendolyn is no ordinary servant. She doesn’t hide behind curtains, or move about through secret passages. Inside these walls, she is respected. Yet there’s no title for her. No title for me to that matter, but I am temporary, not oft needed. Gwendolyn is the only one privileged enough, apart from his wife and children, to place hands on the King.

“Speak,” the King intones.

A large man, he has a voice to match, his words rumbling out like a team of Scottish horses.

“Is the royal aspect pleased or displeased?” I ask.

“Displeased in what way?” he asks. “With you? A cog such as you has no bearing on the King’s aspect.”

“No, majesty. In the general sense. I fear may be an imbalance in your humors.”

Gwendolyn stops wiping and moves her head from side to side. A warning.

“Our humors are perfectly balanced,” the King rumbles.

“I see evidence otherwise, your grace,” I say.

Gwendolyn slashes the air with a hand. That’s enough of that.

But I persist, “Your choler seems to be up, eminence.”

“Choler,” the King says.

I say, “Yellow bile, your grace.”

“I know what choler is,” he says through clenched teeth. “And if mine is up, then it is because you have raised it.”

Gwendolyn has fallen back on her haunches. Her green eyes move from the King to me, from me to the King. She has probably never seen him talk to a servant at length or any common person for that matter. Most Kings allow the peasants to appear in the royal court, to beg favors. But not this one, not since the buboes and the rose rings, the fear of breath and touch.

“There is a method that I know of, your grace,” I say. “A method to balance yellow bile. Was told to me by a scribe. Handed down from the Greeks, it was.”

“The Greeks,” the King says. “You presume to bring me wisdom from the Greeks? Can you even read, gong farmer?”

“A bit, your majesty,” I say. “Don’t have formal education, mind. But I do know a thing or two, sire.”

“I don’t care what you know, rodent,” he says. “The time for you to speak is over.”

The King snaps his fingers in the air. A servant scampers from behind a curtain, and stands just over the King’s left shoulder, utterly silent. The servant is thin and tall, and his conical haircut makes him look like a bull’s penis.

“It would please us to see this soil reader minding his own business,” he says. “And his business, after all, is shit.”

The King nods to the royal pot. Bull penis shuffles swiftly toward me, sweeps the pot up in one hand, dumps it on me head, and then dances away, disappearing behind his curtain. No thought, no hesitation, just complete obedience. The sod.

Divine putrescence oozes down me face, crawls into me eyes, and proceeds swiftly towards me mouth. I clamp me lips together, but in the process draw air through me nose, sucking the filth into me left nostril. The King just stares at me. No amusement on his face. He doesn’t even smile. I take some solace in the fact that he’s not enjoying this but that doesn’t stop anger from building inside me. It starts as heat in me loins and rises through me trunk until fire touches me tongue. Just as I am about to heap every insult onto him that’s ever been piled onto me and mine, Gwendolyn strikes like a snake, kicking me hard in the chest. The air goes out from me, excrement explodes from me nose and I gulp for breath. Another mistake. I taste the tang of the royal essence.

Gwendolyn says, “How dare you attempt to impugn the divine aspect, you pig of a man. Get out or I will see you in the pillory.”

Seething, writhing, I consider committing the ultimate sin and striking the King, but sense wins out, as sense often does for someone at the bottom of the beneath. Soil stick in hand, I walk from the royal toilet, through the great hall, and out into the courtyard, a servant silently shadowing me the whole way.

As days go, it certainly wasn’t me best, but it also wasn’t me worst. I settle into me chair beside the hearth fire, a warm bowl of chicken stew in me lap, watching the flames consume the kindling, listening to me da snoring in his chair. Doesn’t have many days left, I think as I watch him sleep. Yet he’ll still be up before high night, ready to collect the waste, to rake the cesspits. Ain’t much of a life being a gong farmer and occasional soil reader, but at the end of the day, you know you ain’t hurt no one and you know you done the best with what was given you.

As I lift the spoon to me lips, the memory of what was in me nose and mouth earlier threatening to disrupt me appetite, I hear a small knock at me door. So, I answer. Gwendolyn, face obscured by a cloak, shoves her way into me hovel.

“What’s this then?” I ask.

When she pulls back her hood, earthen brown hair freely falling across her shoulders, I have to stop meself from swooning.

“I have never seen you act so foolishly,” she says. “The King is not a patient man on his best day. And today was certainly not his best day. But I can’t imagine it was yours either.”

“I only saw what come out of him,” I say. “Not where it comes from.”

“There are unappealing moments in every life,” she says. “Even the King suffers.”

Da wakes from his slumber, mutters a curse, then goes right back to sleep.

“I won’t be long,” Gwendolyn says. “ I simply wanted to apologize for what I did. I added injury to insult.”

“I know why you did it,” I say. “If’n I’d said what I was thinking, me da would have naught to bury. Not even a little finger.”

“Aye,” she says, the Irish-born tongue apparent. “I also wanted to tell you that you were right. The King has not been himself. There is dissent in the court, and the plague has come to London. He has been rash and angry.”

“Which of those is unusual for him?” I ask.

You don’t understand,” she says. “One of the servants was flogged yestereve for raising a clatter in the kitchen. He did not survive, the lamb. I’d not like to see the same happen to you.”

“Thank you for what you done,” I say. “I ought to have controlled me tongue.”

“We both know that’s not easy for the likes of you.”

"'Tis true enough," I say. "The method I spoke of for balancing yellow bile involves placing the whole of the body in hot water. He may be willing to listen to you."

"The King thanks you," she says.

"Ain't for the King," I say. "Goodnight to you, Gwendolyn."

"Goodnight to you, Seamus."

With a nod and a smile, she pulls up her hood and departs. They move swiftly and silently in the castle, like mice afraid of a giant cat, but Gwendolyn’s grace is not a child of fear. She was born with it. As children, we used to climb the eaves of barns and stables, trying to reach the precipice. I would always lose me nerve, and end up inching me way back to safety. Gwendolyn, though, moved like a squirrel, finding grips and crevices on every surface.

Me Da wakes with a groan, and stretches his shoulders, joints creaking, popping like wet wood in fire.

“Nice to see Gwendolyn,” he says.

“Aye,” I say.

“Need a moment,” he says. “A moment and then we can start.”

“Want to rest tonight, Da?” I ask. “Can manage on me own.”

“Nah,” he says. “Bridget doesn’t like you. Won’t cooperate. You'll end up tipping the cart again.”

That was true. Our mule Bridget was as difficult and unyielding as a country priest. For everyone but Da. Last time I had her out, she chose to bolt, and in her flight, the cart tipped sideways. What a mess.

"Not all gong farmers read soil, you know," Da says after heaving a yawn. "Me father didn't. He thought I was soft-headed for me interest."

Tells the same story every night before we rake. Not sure if he forgets having told it, or if he tells it to remind me we're not just gong farmers. No, we don't just gather shit, we poke around in it, read it, like an old woman reads tea. But what does it amount to? You help where you can, find what ails them, but what thanks do you get? A bucket of waste on the head?

"No, he didn't understand at all," Da says. "Got awful upset with me when I told everyone what I could read from a movement, but word traveled as it often did. There was a local headman whose wife was more ill than well. He heard what I could do and called on me one day. Had me watch as she evacuated, had me listen. I could tell something wasn't right. So I took a stick, pulled from a nearby birch, and started sifting. I noticed a sweet smell alongside the usual foulness."

I look over at him with squinted eyes and say, "You've never told me this before."

"Nah," he says. "But after what I assume was a disheartening day, thought you needed to hear it."

"Well go on if you're gonna go on," I say.

"I told the headman he needed to watch the cooks, and so he did. Caught one of them poisoning the food, but not all of the food, mind."

"Just the wife's food," I say.

Da nods and asks, "Why is that, do you suppose?"

"Could be any reason," I say. "Jealousy. Old rivalry. Fear of an heir."

Da touches the side of his nose. "Fear of an heir. The headmen where we come from used to take more than one wife. Not so much anymore, mind. Not since they've been dunked and converted."

"Of course not," I say.

"The headman's second wife, the wife of occasional favor, was trying to do away with the first, trying to make sure her child was the king-born. But she failed. The first wife recovered soon enough and had a son. His name was Brian O'Neill."

"Da," I say, shaking me head. "You've never lied to me. Don't start now just to make me feel better."

"On your mother," he says.

The weight of this brings me back to me chair. I sit down heavily. Brian O'Neill, king of Tyrone, the martyr of Creeve, come to power through shit? I lift the stew from the rough side table and take a bite. Lost its warmth, but it’ll do. Nothing else concerns me after hearing that me Da is a kingmaker.

Da looks at me and leans forward, resting his elbows on his narrow knees. He sniffs, then keaks.

“What’s funny?” I ask.

“Never thought I would say this, considering our lives, but you smell awful.”

“Aye,” I say. “The royal arse might think itself a rose, but it certainly doesn't smell like one.”

Da laughs.

I raise a spoonful of stew in his direction and say, "To Brian O'Neill."

About the Creator

Mack Devlin

Writer, educator, and follower of Christ. Passionate about social justice. Living with a disability has taught me that knowledge is strength.

We are curators of emotions, explorers of the human psyche, and custodians of the narrative.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.