Double, double toil and trouble;

Fire burn and caldron bubble.

Fillet of a fenny snake,

In the caldron boil and bake;

Eye of newt and toe of frog,

Wool of bat and tongue of dog,

Adder's fork and blind-worm's sting,

Lizard's leg and howlet's wing,

For a charm of powerful trouble,

Like a hell-broth boil and bubble.

Double, double toil and trouble;

Fire burn and caldron bubble.

Cool it with a baboon's blood,

Then the charm is firm and good.

When Katharina is being detained, she yells these words at her enemies.

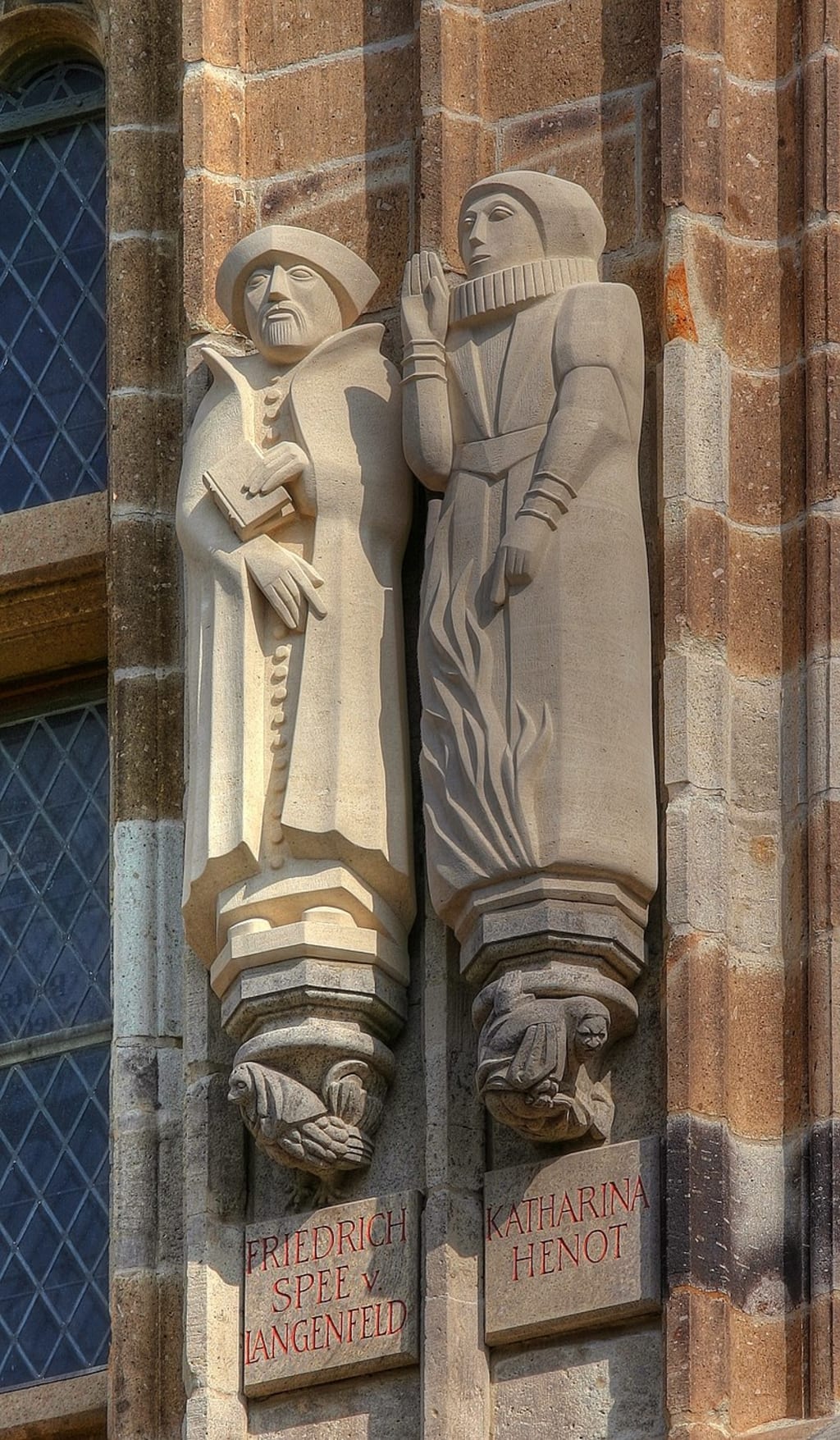

The most well-known victim of the Cologne witch hunts was Katharina Henot (sometimes spelt Henoth; born presumably between 1570 and 1580; died May 19, 1627 in Cologne-Melaten). She was a patrician of Cologne. She was burnt after being allegedly burned and strangled.

Katharina Henot was born in 1617, the daughter of postmaster Jacob Henot and his wife Adelheid de Haen. Her parents were Calvinists who moved to Cologne from the Netherlands about 1570 and earned citizenship after converting to Catholicism in 1576. Several of her allegedly more than twenty siblings, including the Cologne Canon Hartger Henot and the Poor Clare Margarethe (religious name Franziska) at the Poor Clare abbey of St. Clara, most likely perished early.

Seraphin Henot, like his brother Hartger, was already in the service of Archbishop Leopold of Strasbourg at the beginning of the 17th century. As the Murbach abbey's head bailiff and witch commissioner, he also served as a judge in a number of witch trials. Following his abdication in 1625, the bishop did not remain in office for long and was imprisoned for a long period during extensive court proceedings. He passed away in 1633 or 1634.

Katharina had two husbands. Her first husband, Heinrich Neuden, was a mail manager and her father's deputy before becoming a customs officer and waiter for the cathedral chapter in the Zons in early 1604. He passed away in October 1605. Katharina and Hartger Henot's efforts to make their brother Seraphin their successor failed. Katharina married Johann Albert Maints, a customs official and waiter in Zons who died in mid-1614, after Neuden died.

The later marriage resulted in a daughter, Anna Maria Maints, who, like Katharina's sister Margarethe, became a Clarissin in Cologne's Clare monastery in 1622. In Zons, where Katharina also owned a house, she and Wilhelm Stroe, the husband of her sister Jakoba Juliana (after 1641) and her husband's successor, got into such a fight with the bailiff Wilhelm Salentin zu Salm-Reifferscheidt in 1614 (1580 -1634) that she had to seek protection from the Cologne cathedral chapter.

Her father, who had previously worked in Cologne as a silk dyer and factor in the Genoa-based Garibaldi trading company,[4] took over the postal administration in Cologne in 1578. Although Postmaster General Leonhard I von Taxis contractually guaranteed Jacob Henot the very profitable post mastery until the end of his life in 1600, and his son Hartger, despite being a priest, was guaranteed the successor, he was dismissed in 1603 by Emperor Rudolf, who replaced Lamoral von Taxis' father as postmaster general.

For years, Jacob and Hartger Henot fought against this judgement. It wasn't until 1623 that Hartger Henot persuaded Emperor Ferdinand II to restore his father, who was now over 80 years old, with the promise of a lifetime license. Lamoral's son, Leonhard II von Taxis, attempted unsuccessfully to take action against it at first. Jacob Henot died in November 1625, only two and a half years after his reinstatement.

His children had him buried in secrecy so that the postmaster's licence would not be contested. The subsequent legal fight, which reached the Reichshofrat, culminated on October 19, 1626, with the Henots eventually losing the post office, against which they filed a claim for damages.

Katharina Henot was a rich and generous woman. She gave to religious institutions such as the convent where her sister and daughter lived and the cathedral chapter, as well as lending money. The Archbishop and Elector Ferdinand of Bavaria received 4,600 gold guilders and 8,800 Reichstaler.

Possession cases happened in the Poor Clares convent in Cologne in the spring of 1626. A possessed lay sister accused the conventual Sophia Agnes von Langenberg, who was practically worshipped as a saint at the time, of witchcraft. One of the afflicted lay sisters revealed during the exorcism that Katharina Henot had forged an agreement with the devil, which triggered the attacks. The possessed could only be healed if Katharina Henot was punished. This rumor quickly circulated outside of the monastery.

Franziska Henot, one of Katharina's sisters, lived at the St. Klara convent. On January 22, 1627, she was sentenced to Lechenich jail for witchcraft; their fate is unknown (+ 1641?). Because Katharina's daughter, Anna Maria, also resided at the 'Klarenkloster,' "the postmistress," as a wealthy, philanthropic widow, must have been well known to everyone. And the fact that she gave by scent was well known, and it was a source of contention for many.

Fate had its way.

In the summer of 1626, rumours spread that Katharina Henot was a witch. This was rare for a woman of her standing, especially at the start of a series of trials. Katharina didn't take the chat seriously for a long time. She assumed the "common shouting" was coming from the Clarenian monastery, i.e. a church setting.

Katharina Henot protested to Vicar General Johannes Gelenius in a defense letter in August 1626, demanding that he suppress the rumors. After receiving no response, she wrote to the archbishop on 25 October, six days after losing her postal license, requesting that a clerical commission look into the sources of the rumors. The archbishop, however, submitted the issue to the High Secular Court. Lorenz Mey, Katharina Henot's lawyer, was meant to put together the "Expurgatoriales," but he was still too occupied with the court dispute over the post office over the Christmas vacations of 1626/1627, thus the case dragged on.

On August 29, 1626, she filed a complaint with the relevant Vicar General Johannes Gelenius. He was already in communication with the High Spiritual Court and the High Secular Court, and he was dealing with the "events" in the St. Clare Monastery. Katharina wrote to him, blaming herself for the pain of the two "possessed lay sisters" (epileptic seizures?). be held accountable for the exorcism. They also said that the only way to get free of the infatuation was for Katharina to face the full power of the law since she had made a contract with the devil. The Vicar General made no comment, and the rumors propagated further.

On October 25, 1626, Katharina petitioned Archbishop Ferdinand von Wittelsbach to have the rumours examined by an ecclesiastical committee. The archbishop, like Gelenius, might have sent her case to the High Ecclesiastical Court, whose eminent judges permitted repentance and often gave mild church penalties, such as B. Prayers, pilgrimages, and temporary banishment from church events. However, he did not hold the High Ecclesiastical Court accountable for this secular woman's denunciations from the monastery. Despite the fact that the Archbishop knew Katharina Henot well, having loaned him 4,600 gold golds and 8,800 Reichstalers , he referred her to the High Secular Court. Was that a death sentence in the making?

Sophia Agnes von Langenberg, who had been imprisoned since May 1626, stated under torture that Katharina Henot had performed dangerous magic with her in the Poor Clares monastery as early as October/November 1626. Magdalena Raußrath, a former maid of Katharina Henot and a lay nun of the Poor Clares monastery suffering from "possession," accused Katharina Henot of witchcraft before the Cologne city council on January 8, 1627.

In December 1626, Katharina's lawyer, Lorenz Mey, requested to the HWG for a purgation process to release her from the allegation of witchcraft. However, the formalities took their time. Nobody looked eager for a swift and favorable resolution to the "Henot case."

On January 9, 1627, the council, led by mayor Johann Bolandt, arrested Katharina Henot at the residence of her brother, the deanery of St. Andreas.

Her bail plea was denied, and she was denied sufficient defense. Two days following her arrest, Archbishop and Elector Ferdinand of Bavaria refused to admit defense attorneys and maintained his position. On January 18th, she was turned over to the High Secular Court. Contrary to the norms of the Constitutio Criminalis Carolina, she was refused legal and medical help. Her sister and children were held and questioned as well. Sister Margarethe was transported to the electoral fortress of Lechenich, where Sophia Agnes von Langenberg was also imprisoned, after being accused of witchcraft by von Langenberg. The Elector eventually demanded more than 1,000 Reichstaler from the monastery for the inquisition procedures against her and Langenberg.

The accusation against Katharina Henot was made up of four parts: the accusation by Magdalena Raußrath, the tortured statements of Sophia Agnes von Langenberg, the accusations of witchcraft by various monastery maidens, and the fact that Katharina Henot had refused to allow the purgation process to begin.[8] Katharina Henot refused to confess after being tortured three times. She recounted to her brother in a letter about the second torture interrogation (March 15, 1627), which had lasted more than five hours.

She had been accused of casting harmful spells, including killing a child and three men, including the cathedral chapter's canon priest, Lucas Weyendall. She is also accused of causing a miscarriage and having sexual encounters with many charges. She also incited a caterpillar plague at the provost of St. Severin and a feud between the canons of St. Andreas, of whom her brother was a provost, and "the Halffman zu Welffen" (tenant of the "Walhoven" estate at Dormagen). She called all of the claims slander and provided witnesses who could swear that her remarks were true.

The Walhoven renter was perhaps disgruntled since she had "contributed 1,500 acres of land" to the abbey, as evidenced by preserved papers. According to the statute in effect at the time, the Constitutio Criminalis Carolina, defendants had to be released if extorting a confession, even by torture, was impossible. That did not occur. The mandate acquired by her brother from the Reich Chamber Court, as well as any petitions and concerns from her family and acquaintances, were not considered.

Despite the fact that she did not confess after being tortured three times as allowed by law, she was condemned as a witch. On May 19, 1627, the Wednesday before Pentecost, lay judge Dr. Romeswinckel - Rhineland witch commissioner - condemned to death in the cathedral courtyard."

"Decision in the sorcery case involving Katharina Henot. In the embarrassing case of Katharina Henot, it is rightly acknowledged that the evil person brought to trial for renunciation of God Almighty and his beloved saints, abuse and dishonor of the most reverend holy sacrament of the altar, carnal mingling with the annoying Satan, magic dances on the Neumarkt, diabolical conspiracy, sorcery committed against people and fruits, and for the murder of people of rank and children, are publicly led in an execution. The thought sentence is moderated, however, to the effect that the imprisoned person should be brought from life to death with the rope and the dead body with them to be burned to ashes by fire. This is because we have received a reliable report from the reverend Mr. Vicario in spiritualitualibus that the imprisoned person sincerely regrets and weeps for the sins he has committed. We, Greve and lay justices of this Electoral Secular High Court in the city of Cologne, denounce and condemn them.”

She was strangled by the executioner at the Melaten execution site near Cologne on May 19, 1627, and her body was then burnt at the stake. In the presence of two witnesses, she proclaimed her innocence to notary Johann Christoph Rosch on the way to the execution site.

Executioner Silberacker dragged her to the "Blue Stone" in the cathedral courtyard and yelled, as had been customary in Cologne with death sentences for centuries: "I'm dying You on the bare stone, don't kiss ze lebdag no Vader en Moder nit me home!" Greven, the city's chief judge, broke the staff of the righteous over her as a sign of justice. Then Katharina Henot was hoisted into a wagon while being bound. Adrian Horn and Hermann Mohr, two confreres of the Jesuit Friedrich Spee, sat to her right and left, respectively. Both were in favour of the witch trials and believed that they were a holy obligation owed to the witch cult or a vital church mission. The procession of the executioners then left for the execution site from the heart of Cologne. Many observers who were meant to discourage people from Katharina's claimed misdeeds followed her on her final voyage with a death sentence, transfer, and cremation on Melaten.

The trial of Katharina Henot was followed by more witch trials. Between 1627 and 1630, 24 of the 33 defendants were burnt at the stake. Margarethe, Katharina Henot's sister, was freed in 1628 after a lengthy pre-trial imprisonment, whilst Anna Maria was only temporarily imprisoned in Lechenich in January 1627 to confront Sophia Agnes von Langenberg. Hartger Henot, Katharina's brother, condemned his sister's execution as a judicial murder. Hartger Henot continued to strive to prove his sister's innocence even after her execution. He did not file a claim for compensation for the loss of the post office.

In opposition to Katharina's execution, Hartger Henot, the spiritual brother, resigned from all church positions. He requested permission from the archbishop to print the case records. He originally concurred since he believed the procedure to be lawful. But then issues emerged. Most likely, the mayor or a court councilor objected to publication. Hartger Henot ultimately only obtained information about the trial from an excerpt from the family's materials filed to the archbishop in support of their defense. The documents have not endured. Therefore, it is still unknown what circumstances led to Katharina's execution.

Was it only jealousy of the wealthy widow or a significant indictment of the "possessed nuns"? Or maybe there were more factors at play, such as the conflict over the postal license, the elector's financial obligations to Catherine, or even the Henot family's adherence to the original Calvinist faith. Hartger Henot established a study foundation with the remainder of Katharina's bequest that supported the Henot family's pupils long into the 20th century. The sole case in which the prisoner was found guilty despite being tortured repeatedly and refusing to confess was Katharina Henot's death.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.