A Woman of the Plains

The Question of Survival

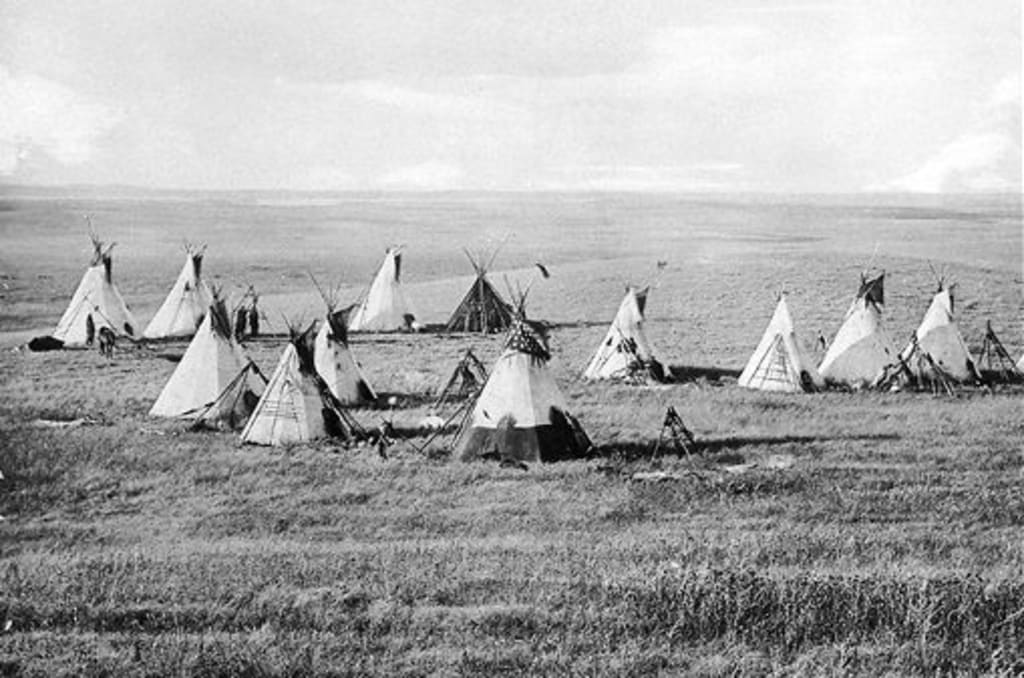

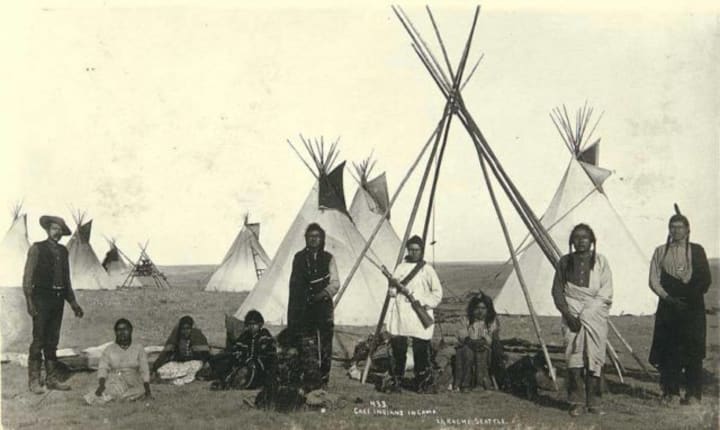

The year is 1750 and I am a Paskwaiwiyiniwak woman living on the banks of the Kisiskaciwani-sipi river in the area referred to as Alberta during the 21st century. They call us the Ndooheenou people, a nation of hunters, for we are a nomadic people, following the migration patterns of the wild animals and birds in this area. As nomads we do not have specific occupations. Survival dictates that everyone, in the tribe, is capable of doing whatever task is needed in the moment. We work as a team, not as individuals. The only division is that between men and women. The men are typically the hunters who supply us with meat and the warriors who keep us safe from predators as well as the other tribes who inhabit this area: the siksikartsitapi in particular, who would wipe us out in a moment, if ever given the chance. The men are also responsible for making the tools we use to survive, from stone, wood and bone. The white man, with the convenience of metal, has yet to arrive in our area.

As a woman, I have myriad of tasks that I, along with all the other women in the tribe, am responsible for. The first and foremost is tending the fire, for without it, especially in the winter, we would not survive. This includes working with the children, ensuring that we have a constant supply of fuel on hand to burn. We also are responsible for the food we eat, gathering the wild rice, berries, and roots in the forests and butchering the meat along side the men, after a successful hunt. We use snares to capture smaller animals for our meals and dry fish, meat and berries for the winter. A major task in the summer is making pemmican, a mixture of buffalo meat, fat and saskatoon berries that grow in abundance in this area of the world. This pemmican becomes our major source of energy throughout the cold winter months. We use the hides of the animals to create our teepees, blankets, clothing and footwear. We gather bark, roots and leaves from the wild to make medicines that have kept us alive for generations and we are responsible to hand this information on to the younger generations. We pack up and move the camp, using dogs as our pack animals: the teepee poles now converted to travois, as the men scout the area for a new site, close to game. During the winter we keep ourselves busy inside the teepees, decorating our clothing with porcupine quills and other items gathered in the wild, creating baskets and bowls from grass, birchbark and other materials. Nothing is wasted. Everything has a use.

As I reflect on why I have chosen this woman to focus on, I know first and foremost that I have a unique connection to these people of the past. Is it because I was once one of them in a past life? Or, is it because feeling that connection has led to years of study in this area, filling that need for understanding that often makes little sense to me? I am aware, that as a farm girl growing up in the north, I have learned to harvest my own food, whether it be from the barnyard, the garden or the forest which would give me an advantage over many. I have camped outdoors in the winter, surviving in minus-forty-degree temperatures, albeit it with the stoves, clothing, and sleeping bags of our current era to protect me. I have learned how to set-up a teepee, and know pleasure of sitting beside it’s fire keeping the chill of the night air at bay. I have also had exposure to the tools of the time, as our farm was located on an ancient lake bottom. My father was constantly bringing in arrowheads, spear heads, knives, and even a tomahawk from the fields to add to his collection. The question I would love to explore is whether I would be able survive using only the tools available at that time in this location. I fear it would be much harder and more frustrating than I can imagine.

One winter I decided to replace the commercial fur on the hood of my parka with a rabbit pelt I had acquired from the Northern Store. For hours I fought with the needle and thread, trying to get them through the fur without much luck. In dismay, I gave up for awhile, all the time wondering why it was impossible for me to do something that humans have done for thousands of years. Finally, I returned to the task and discovered the secret. One has to go through the pelt from the inside out towards the fur, not the other way around. Once I learned this, I was able to finish without a problem. In the midst of this, I was amazed as I thought of one generation passing on this information to the next throughout the years, a lesson which has been lost to our current young people as they focus on computer screens instead of learning how to survive on this planet.

For me, this is the most relevant question we may be forced to answer in the future. Can we survive? We look up from our screens thinking we are so smart, so advanced, in the midst of not having a clue how to feed ourselves, much less provide our own clothing and shelter. Everything has been handed to the current generations without thought of where it came from or how much energy it took to create. Ridiculous suggestions are thrown about such as replacing one’s lawn with a vegetable garden with absolutely no consideration of the amount of effort it takes to do this. One year I hired my grandson to help in my garden. He lasted an hour before heading back into the house to create a garden on his ipad. He claimed real gardening was was just too hard as he swiped his finger across the screen. Magically the plants appeared, ready to harvest. Sadly, they have no nutritional value.

As humans we like to claim that we are always moving forward. Everything is bigger, better, smarter and more amazing than it has been in the past. This is true when it comes to certain technical advances such as our cell phones, but the question we all must be prepared to ask ourselves is, “how do these advances ensure our survival as a species?” The fact is that the human body has needs; needs, which if not met, will lead to its demise. Needs that we must pay attention to as individuals, in order to ensure our survival. Needs which the majority of the population completely ignore. Yes, we eat, we drink, we sleep and so on, but we do this without considering for a moment the amount of effort others have invested to make this possible for us. If they stop, what will happen?

The people of the plains in 1750 knew how to survive in their environment based on the lessons learned and passed on by generations before them. They didn’t live like they did because it was a choice they had made. They did it because they needed to, in order to survive. Everything changed when the white men arrived in 1754. These people were not stupid. They knew a good thing when they saw it and understood the reality of accessing the tools of the white men as quickly as possible, whether it be kettles and knives for cooking, fabric for blankets and clothing or guns for hunting. They adapted to their new reality very quickly, switching from hunting for food, to hunting for furs that they could use in exchange for the goods that would make their day to day lives so much easier. Within a just over a hundred years, they lost the skills that had allowed them to survive for generations.

In 1885, a group of Metis (descendants of the French trappers and aboriginal women) joined together with a few of the chiefs and their men on the plains. They raised a small, short-lived rebellion, demanding that the Canadian government protect their rights as a distinct people. Small battles were fought in Duck Lake, Fish Creek, and Cut Knife before the final defeat, known as the Battle of Batoche. Historical accounts of this time, written by the English and the French, don’t make much of this rebellion, claiming it only a small blip on the settling of the west and the creation of the prairie provinces. However, the accounts of the tribes of the area tell a much different story.

The Metis-led rebellion did little to scare the government of the time, but it wasn’t as true for the white people in the area. Although only a handful of the chiefs and warriors in the region had joined the Metis, the settlers feared everyone who had aboriginal blood. They closed down all trade with the aboriginal people for years, leaving them to fend on their own again. The problem was that these people no longer knew how to survive without the tools of the white men. They had no bows, arrows or spears to hunt with and wouldn’t have known how to use them if they did. The guns that they had acquired were useless without ammunition. No one had been teaching them how to harvest from the wild, which meant they had no idea what was safe to eat and what wasn’t. What’s more they had even forgotten how to start a fire from scratch, having relied on matches for so many years. Starvation and illness ran rampant throughout the reserves, leading to countless deaths. In the end, those who survived only did so because of the few elderly women, who had continued to hang on to the knowledge of the past, shared it with the others.

We have all been taught the basis of evolution. Charles Darwin stated “it is not the strongest of the species that survives, nor the most intelligent. It is the one that is most adaptable to change”. This implies that change is good. That we are always moving forward, but are we? Our fascination with dystopian literature suggests otherwise and may indicate something deeper. Something more profound. For the question it attempts to answer is, “how does one survive?” Archaeological evidence clearly indicates that societies and civilizations have flourished and then completely disappeared throughout the history of mankind. As I watch the focus of our current generation, I wonder. Are we on the edge of another great collapse? If so, we need to learn the lessons of survival from the past or we will not make it through. Thus, if given the chance, I would choose to become a Paskwaiwiyiniwak woman.

End note: When I started writing this piece, I was headed in a completely different direction than where I have landed. My initial thoughts were based on the following photo. I have decided to include it to demonstrate the mess we are currently making with our throw away society, one of the reasons may well lead to a collapse of all we consider normal.

About the Creator

Gail Wylie

Family therapist - always wanted to be a writer. Have published books on autism. Currently enjoying trying my hand at fiction. Loving the challenges of Vocal. Excited to have my first novel CONSEQUENCES available through Amazon.

Reader insights

Outstanding

Excellent work. Looking forward to reading more!

Top insights

Excellent storytelling

Original narrative & well developed characters

Heartfelt and relatable

The story invoked strong personal emotions

Comments (11)

Great job!

Great job writing down your people's stories. And congrats on your top story.

Excellent work. I am also a descendent from an Iroquois nation in the East. We should all take lessons from this article. There is nothing wrong with doing things in an old fashioned way for at times that way is better.

This is an excellent and well-deserved illuminating Top Story. We have featured it in this week's Vocal Community Adventure in The Vocal Social Society on Facebook and would love for you to join us there.

Dear Ms. Wylie - So inspirational and such a lovely well crafted presentation - As I scroll through your gorgeous headings *I've subscribed to you with pleasure. I want to say how amazing, even as cultural metaphorical quips might be, we all seem to relate. I so love learning about diverse cultures ~ I thank Vocal Brass for setting this link up for all of us - Jay Jay Kantor, Chatsworth, California 'Senior' Vocal Author - Vocal Author Community -

Excellent piece and well done on being Top Story. It's interesting that guns and pots and blankets were high-tech in the 1760s, like corporate farms and AI is today. Different times, the same results - a loss of independence and a shortsighted reliance on others as benefactors - when they're not. Cheers.

Congratulations on the Top Story! I really enjoyed all of the thought you clearly put into this piece.

Survival skills are still far more important than most people would even want to consider. Great story, well deserving of the Top Story pick!

Love this!!! Wonderfully written and captivating!!!❤️❤️💕

I actually started writing about the aboriginal people, I have a deep love of their way of life. I started with the rain dancers. I speak to the young ones about such a way of thinking as yours, they think it is funny my encouraging them to be independent and not rely totally on what is handed to them. Is it too late for our world. I completely enjoyed your journey from strength within a people to where we are today. I worry for us. This was sad, true and very scary,

Very enjoyable read! A great description of what life might have been like at that time compared to life as it is today.