Ida Lupino (1918 - 1995)

Film and the Politics of Negotiation

If you haven’t seen Barbie, you’ll have heard of it right? It’s big news. It is the female directed movie that has made $1billion, in just over a fortnight from release and is now heading towards the $2billion mark.

It is both a frothy, fun, highly stylised film and a film about living under a particular brand of patriarchal capitalism. It is about patriarchy and capitalism and made under patriarchal and capitalist conditions. And how do I know that? Because its success is measured in dollars and it is newsworthy because it female-directed.

And women don’t make films, especially not star-studded, summer block-busters.

And when I say women don’t direct films – of course this is hyperbole. But let me just indulge my 1940s Hollywood screen writing persona – in which case what I have just written is almost completely true. In the 1940s there was only one woman in the Directors Guild of America – Dorothy Arzner. And she retired in 1943 after a near fatal bout of pneumonia.

Between 1943 and 1949 no films in Hollywood were directed by women. The woman who broke that streak was Ida Lupino.

Above is a picture of Ida Lupino – when she was being marketed as the British Jean Harlow. She had been successful in the UK, playing the ingenue role in a couple of movies and had travelled to the UK to audition for Alice in Wonderland. Of that time, Ida said:

“I was such a wretchedly, unhappy painted doll.”

Above is another picture of her starring in They Drive by Night (1940) with George Raft and Humphrey Bogart. She wanted to be taken seriously so grew out her bleached blonde and lost some weight.

In this film, she is the femme fatale, attempting to frame George Raft’s character for murder. She is delightfully unhinged in her portrayal. It is very much a film of its time, spelling out the economic precarity of the truck drivers. The dangerous driving of the men is seen as ambition, whereas Lupino’s characters ambition is seen as aberration, her desire as a threat to men.

Despite the big eyes and button nose, she got to deliver some gritty roles. She described herself as the Poor Man’s Bette Davis – often cast in roles that the bigger star turned down.

And she wasn’t above turning down roles herself. Under the studio system, which could make films about how some industries mistreated the workers, actors who didn’t play nice were faced with suspension. And it was during suspension that Ida got to observe the art of film-making from behind the camera:

“For about eighteen months in the mid 40’s I could not get a job in pictures as an actress… I was on suspension… when you turned down something you were suspended… I was able to keep alive as a radio actress. I had to do something to fill up my time… I learned a lot from George Barnes, a marvellous cameraman.”

When I started writing about classic Hollywood it was because I wanted to uncover how the movie business only allowed certain stories to be told, how the studios pigeon-holed performers and at worst cut lives short. I felt haunted by the stories that weren’t made, that couldn’t go on to shape our world and the performers who paid the price.

Ida doesn’t really fall into that category. She was successful in ways that many others couldn’t be, as a writer, actor, producer and director. And when the big screen didn’t come calling she continued to forge a career in TV, acting and directing across a range of programmes.

But there is still something troubling. Because even in the stories that get told there are traces of other stories that might have been.

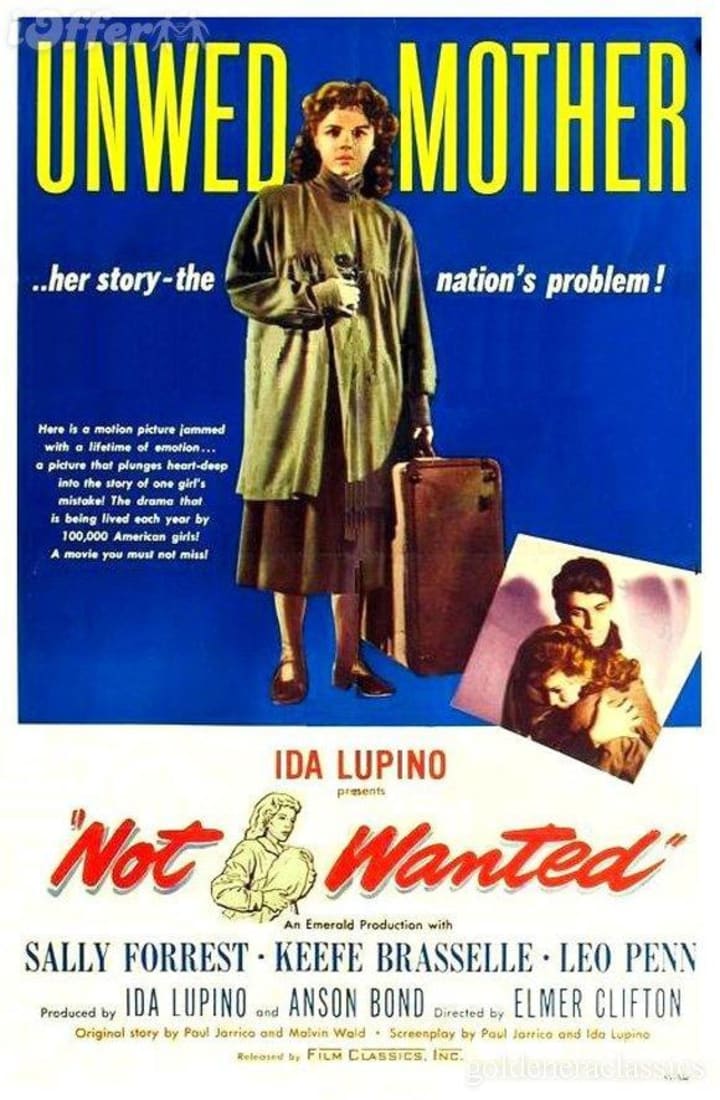

Ida’s directorial debut was Not Wanted (1949). This was the first film to be produced by The Filmakers Inc., the company founded with her husband Collier Young and screenwriter, Marvin Wald. She is not credited as director as before shooting was properly underway, Elmer Clifton had a heart attack, and she took over the role. She has a writing and production credit, but out of respect for Clifton his name remains as director.

The Filmakers Inc. had a very short business life and operated from 1949 to 1955. In that time they made 8 films – 6 of which Ida directed.

The ethos of the company was to produce social realistic films, that documented the real, messy, fragile lives of everyday people. Ida described this to the New York Herald Tribune:

“We are trying to make pictures of a sociological nature to appeal to older people who usually stay away from theatres. We are out to tackle serious themes and problem dramas.”

There are definite themes resonating throughout her work of this period.

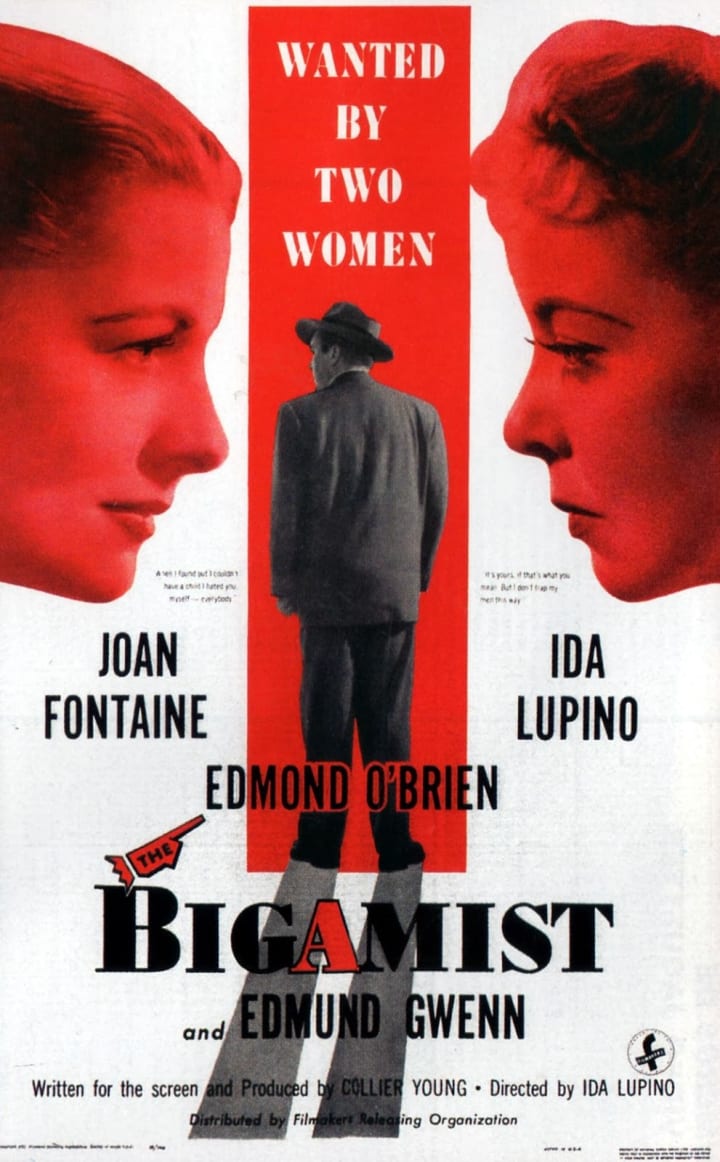

Her films pose moral questions and her work strains at the edges of what is allowed under the Production Code. In Not Wanted, she takes on unwed motherhood, from the perspective of the young woman. In Outrage, she documents the trauma of rape from the point of view of the victim. Rape is never mentioned. It could only be called “criminal assault” because of the code. In The Bigamist, she looks at the constraint of gender roles and middle-class respectability. She shows an interest in the “poor, bewildered people.”

Many of her characters are compelled to run away, further untethering of fragile lives. But in running away they find a stranger with compassion. Compassion is presented as the highest moral choice.

They are films aware of their historical context. The shadow of World War 2 looms heavy, with characters, injured and left behind, forming surrogate families.

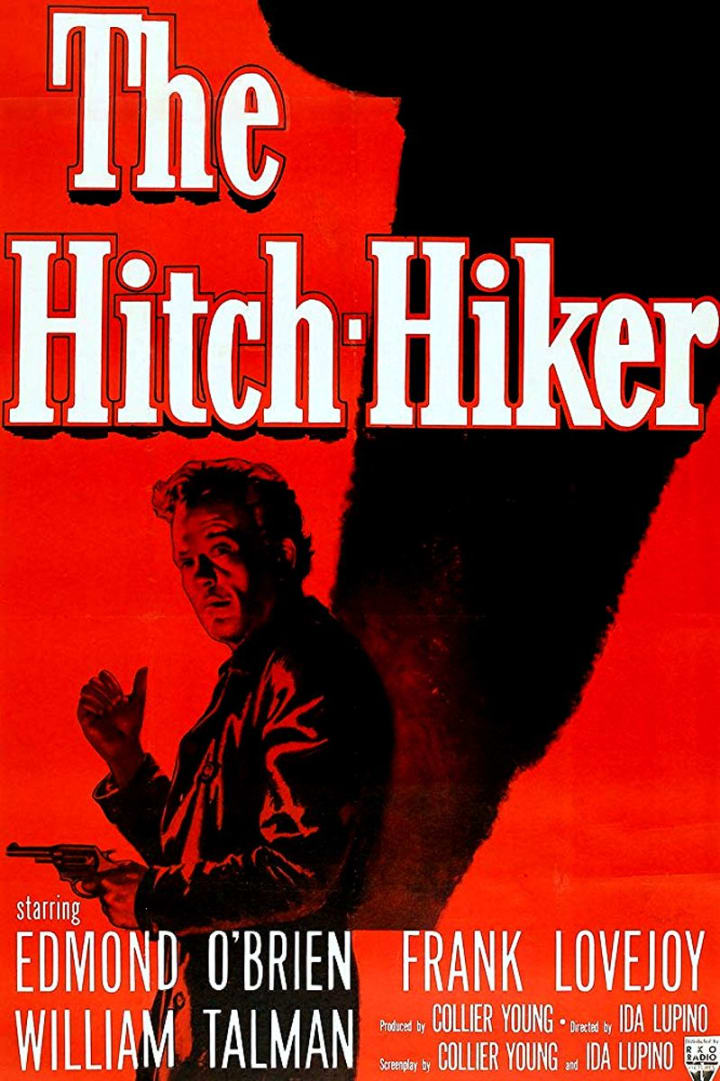

And stylistically, the films, all low-budget and black and white, capture the style of the era: noir lighting, cityscapes, suspense, the psychological depiction of fear through flashback and narration. All of the films share the sparsity of a good short story.

They are ground-breaking films. In The Bigamist, Ida Lupino becomes the first woman to direct herself in a feature film. (It was a shrewd marketing move to cast herself and Joan Fontaine as the two wives. The screen writer Collier Young was Ida’s ex-husband and was married to Joan Fontaine at the time of the film.)

In terrifying form, The Hitch Hiker, Ida directs an entirely male cast working with an entirely male crew. The film showcases her penchant for the dark and sinister.

But Ida Lupino’s work was also a negotiation. While directors are seen as auteurs – the ones in control of the vision, of the story - Ida’s experience is slightly different.

As she says in her autobiography, Beyond the Camera:

“There was an absolute and iron-clad system in the film capital in the 1940s and 1950s, which it seems to me, had its primary purpose to exclude females.”

But she also says:

“I hate women who order men around, professionally or personally.”

And so she developed a style of directing which was about wheedling and flattery:

“You do not tell a man; you suggest to him. ‘Darlings, Mother has a problem. I’d love to do this. Can you do it? It sounds kooky, but I want to do it. Now can you do it for me?’ And they do it – they just do it.”

Look at how many words women have to use.

She would definitely not see herself as a feminist, or crusader. It was not good movie business sense to do so.

Whilst negotiating control of her films, she was involved in trying to secure US citizenship. Negotiations with the FBI and the House of Unamerican Activities may also have compromised her ability to deliver stronger messages in her films. (She would describe herself as a liberal democrat, a supporter of Roosevelt’s New Deal, but had links with black-listed artists. It is unclear whether she leaked names or not…).

Ida Lupino delivered all films on budget and to time, with story-telling flair.

She held herself to high standards:

“I’m mad they say. I am temperamental and dizzy and disagreeable. Well, let them talk. Only one person can hurt me. Her name is Ida Lupino”

However, Filmakers Inc. finally closed down because it couldn’t get the financial backing it needed and had entered into an unbalanced arrangement with RKO over their distribution rights.

In particular, Lupino’s darkness and quirkiness shone through in her story-telling and provided her with a directing career in TV in series such as Alfred Hitchcock Presents and The Twilight Zone. Martin Scorsese once said of her film career:

“There’s a sense of pain, panic and cruelty that colours every scene.”

She went to great lengths to avoid being commodified as an actress and to give her career longevity but there are still traces of stories left untold.

Her friend Joan Fontaine said of Ida:

“.. the nearest thing to a caged tiger I ever saw outside a zoo. I don’t think she has been still a whole minute of her life… Ida isn’t normal. No one has ever accused her of that. One of her peculiarities is that she does everything well.”

All filmmakers are constrained by budgets, and access to talent and resources. And gender inequality continues to be an issue in Hollywood. But it would be nice to uncage the tiger.

I wonder what Ida Lupino could have made with the budget and the artistic freedom of Greta Gerwig’s Barbie.

If you've enjoyed what you have read, consider subscribing to my writing on Vocal. If you'd like to support my writing, you can do so by leaving a one-time tip. Thank you.

About the Creator

Rachel Robbins

Writer-Performer based in the North of England. A joyous, flawed mess.

Please read my stories and enjoy. And if you can, please leave a tip. Money raised will be used towards funding a one-woman story-telling, comedy show.

Comments (4)

Ida was one of many women who made their mark both behind and in front of the camera. However, she is one of the more recognizable ones of the later generations. In 1919 Mary Pickford, along with actor actor Douglas Fairbanks, Charlie Chaplin, and Director Mark Griffith, founded United Artists. which is still here in a very different form today. Thats not even counting Lucy Ball, who went on to found Desilu Studies which produced some of the biggest television shows of the 1970s. Woman have been making their marks behind and in front of the camera for decades, Only they rarely get the attention or credit hey deserve.

Very good, maybe I'll watch one of her films

Another great read that leaves me wanting to do more research of my own. I always look forward to notifications that you have published a new piece, and am excited to see what I can learn from it

I am so glad you wrote this! I mention her to my media students as an example of a woman in the business who never gave up on either side of the camera. And did you make that last poster yourself, and if so, how? 😉