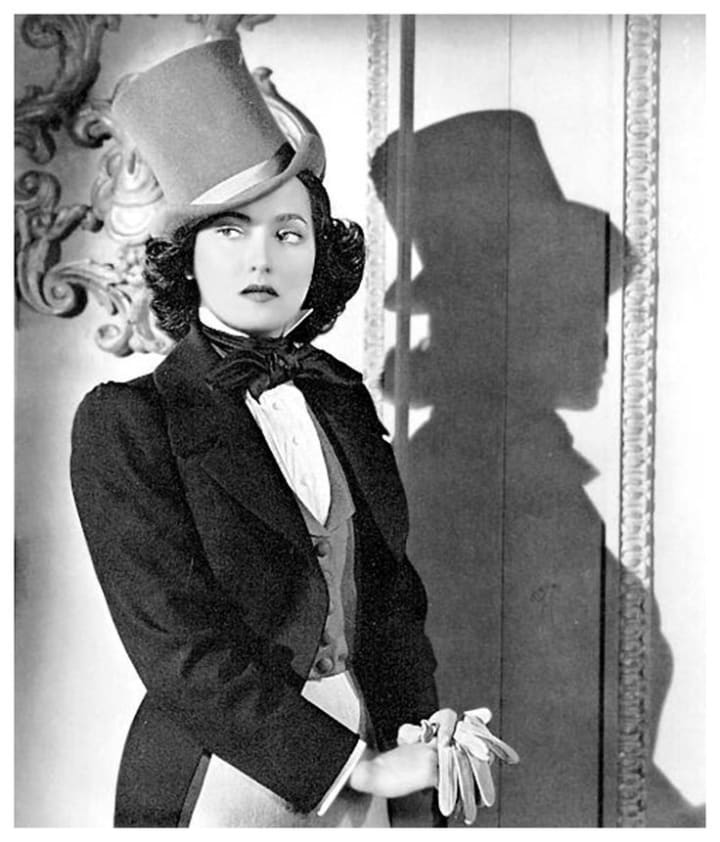

Merle Oberon (1911 – 1979)

Some “Passing” Thoughts

The day dreams have started again. I’m an imaginary 1940’s screen writer and I’m out of ideas. I’ve paced up and down my office lighting cigarettes. I reach towards a book shelf and because I think in film tropes I have to blow the dust off the cover of my hard back edition of Emily Bronte’s “Wuthering Heights.”

What a book, full of cinematic possibilities. Unfortunately though, this novel has only just been on screen. 1939 – Cathy (Merle Oberon) and Heathcliffe (Laurence Olivier) in the bruising, baffling throes of a passion they can’t understand.

Oberon’s Cathy was caught up between the painful choice of her wild, unbridled nature or to be hemmed in by polite, cultured society. It was a masterclass in suppression. And although the film is critically acclaimed there is no Oscar nomination for Merle.

Maybe, if I could find a different novel to adapt, I could get us both nominations…

But then as a 1940’s screen writer I would have no idea that the story of Merle was stranger than any film I would be permitted to write.

Before landing my dream (imaginary) screen-writing job, I first saw Merle Oberon in The Dark Angel (1935) when she played the epitome of a high-class English woman faithfully waiting for her wounded fiancé after World War One. Her accent is flawless, clipped received-pronunciation. This role earned her an Oscar nomination. It was the first nomination for any bi-racial woman.

But nobody, apart from those closest to her, knew that fact until after her death.

The story that was reported as part of her obituary in the New York Times was that she was born in Tasmania to a British Army major who died shortly after her birth. Not long after, the family moved to India. Tasmania – how delightfully far away. And besides all records had been burnt in a fire. And she couldn’t really remember much about it all because she was so very young.

The same obituary points to her “almost exotic beauty” and a “slight slant to her eyes”.

The reality. She was born Estelle Merle O’Brien Thompson in poverty in Bombay. She was brought up by Arthur Terrence O’Brien (a Welsh engineer) and Charlotte Selby (from Ceylon – now Sri Lanka). Charlotte played the maternal role. However, her birth certificate names Constance, Charlotte’s 12 year old daughter as her biological mother. Charlotte had given birth to Constance following rape at age 14 by the foreman of a Tea Planation. Merle was also conceived by rape and no biological father has been identified.

My 1940’s screen writer would have found this fascinating. What a story! But this didn’t come to light until the beginning of this century. It was Harry Selby, one of Constance’s children who made the discovery. He tracked down Merle’s birth certificate to discover she was a half-sister and not his aunt. He kept this information from biographers until 2002.

The story of Tasmania apparently came from her first husband Alexander Korda. Korda was an Hungarian-born British film-maker who made films in Austria, Hungary, the States but settled in the United Kingdom. Korda and Oberon married in 1939 and divorced in 1945. During that time Korda was knighted for his services to the war effort, making the young poverty-stricken woman from Bombay, a Lady.

Merle and Korda met through film. She was an uncredited actress and he was looking for someone to play Anne Boleyn in the Private Life of Henry VIII (1933). He gave her the stage name and her big break as further starring roles followed.

She was supposed to star in Korda's 1937 film, I, Claudius, as Messalina, but her injuries in a car crash resulted in the film being abandoned. The crash resulted in facial scarring, but this is barely detectable in any of her photographs. In fact, her smooth complexion was often commented on as she modelled for Max Factor.

But her complexion was never straightforward. Merle might well have used Max Factor pan-cake to provide her skin’s smooth look. But she also used skin-bleaching products to hide her ethnicity. Skin-bleaching products don’t literally bleach the skin, but instead halt the skin’s production of melanin, by using ammoniated mercury. Because of the risk of mercury poisoning such products were banned in the US from 1936, but they were easily imported (and still are).

Merle Oberon often struggled with skin rashes around her mouth. The problems with her skin came to the fore when she screen-tested for a role in The Constant Nymph (1943). She had recently had the flu and took a sulfa injection. Sulfa was a popular anti-biotic in the 1930s, and is still used in some treatments today. But it does carry the risk of allergic reactions. For Merle, along with the mercury products it caused further rashes and sores. She underwent three derma-abrasion treatments to address this and when she travelled wore a black veil. The screen tests were unsuccessful. The part instead going to Joan Fontaine who was nominated for an Academy Award for the part.

In 1943, she met the cinematographer Lucille Ballard, whilst working on The Lodger. To overcome the problems with her scarring he invented a lighting technique, which highlights the eyes so that the rest of the face looks smokier, or in lower resolution. The light became known as the Obie (after Merle Oberon) or the catch-light. It must have worked – because, reader, she married him. The second of four marriages.

Merle worked throughout the 1940s in the UK and the US, making 15 films with the most commendable being her role as the sexually ambiguous George Sand in A Song to Remember (1945), but none were the break-out hits expected after Wuthering Heights. And there were no further award nominations.

As a 1940s screen writer I might have heard some rumours about Merle’s affairs and her ‘oriental’ background. But only a handful of people knew the truth of her upbringing. And I would have got why she needed to keep it a secret. Hey, I’m British. I know we don’t have a great track record for race relations, and we have a real problem with class. In the UK, there were no laws that forced segregation, but likewise there were no laws that prohibited it either, until 1965. She would have been seen as second class. And in the US in a pre-civil rights era, being a woman of mixed-heritage trying to work in the movies was an impossibility under Hayes Code restrictions, effectively ruling her out of starring roles.

But as a woman writing about it all in the 21st century, with my sense of the importance of identity, I can see a fragmented, fragile life. Her identity was untethered from the start by the circumstances of her birth and no matter how much wool she used to pull over others’ eyes or to wrap herself in accomplishments – it was always prone to unravelling.

“Passing” is a psychological game. A complicated form of peek-a-boo, where the person needs to be seen, but not fully seen. There is a very human desire to belong, but when belonging is contingent on a lie it might feel incomplete. In “passing” the pragmatism of following opportunity is finely balanced against the experiences of being a fugitive, in exile from your own background. An uneasy safety.

It nearly unravelled when she ‘returned’ to the place of her birth – Holborn, Tasmania in 1978. She was to be honoured by the Mayor. However, in the taxi to the reception, she confided in the driver that she had been born in India. During her stay in Tasmania, she would not answer questions about her birth and spent most of her time in her hotel room. She did not visit the theatre named in her honour. She complained of heart murmurs.

Merle Oberon died the following year in her house in California from a stroke. She was 68.

The biggest acting role of her life was her own life.

Earlier this year (2023), Michelle Yeoh took home the Oscar for Best Actress for Everything, Everywhere, All At Once. Commentators described the nomination as being a first for an actress who identifies as Asian. It felt clumsy. It felt like one of those modern clunky descriptors, where we trip over the language to get everything just right. But it was phrased this way for a reason. And that reason was Merle Oberon’s nomination in 1935 for The Dark Angel. A landmark occasion that ‘passed’ without notice.

If you've enjoyed what you have read, consider subscribing to my writing on Vocal. If you'd like to support my writing, you can do so by leaving a one-time tip. Thank you.

About the Creator

Rachel Robbins

Writer-Performer based in the North of England. A joyous, flawed mess.

Please read my stories and enjoy. And if you can, please leave a tip. Money raised will be used towards funding a one-woman story-telling, comedy show.

Enjoyed the story? Support the Creator.

Subscribe for free to receive all their stories in your feed. You could also pledge your support or give them a one-off tip, letting them know you appreciate their work.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.