Unwriting Gender Dichotomy

Let's talk about sex, baby.

With my Facebook feed actively abuzz regarding the recent un-gendering of a plastic potato, it seems like an excellent time to break down the idea of sex as a binary structure.

First things first: gender is not a scientific term.

That’s important, so we’re going to repeat it.

Gender is not a scientific term.

Gender is a societal construct, one that relies on current human behavior and mindset in order to exist at all. Consider: the same group of people well-accustomed to seeing Christian art depicting men in robes struggle to accept modern-day men wearing dresses.

It's far from the only example. For milennia, men wore makeup. When the United States came to be, men still took pride in wearing carefully styled, elaborate wigs.

Yet when modern icons request their pronouns be neutral or are featured embracing androgynous fashion, they face vicious, hateful levels of criticism and condemnation.

Why?

Because it no longer matches what we have been taught about our roles within society’s expectations of our gender - a demonstration of the very fluidity within the concept that should present as examples making it easier to accept variations.

But that’s a talk for a different afternoon. What we are discussing today is physical sex.

And – spoiler – it’s still a roller coaster, friends.

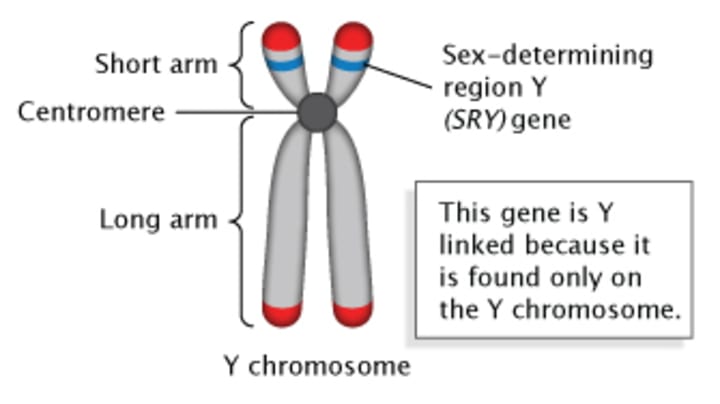

Biological sex, so far as most of us learned it in junior high textbooks, is determined by XX and XY chromosomes. The XX combination generates a female mammal, while the XY combination generates a male.

Technically, this is true. And when addressing third graders, it’s certainly the simplest breakdown.

It is not, however, the end of the story.

Each cell has (typically) 46 chromosomes. The Y chromosome itself is not the gender-defining factor – rather, it contains a gene called the sex-determining region Y gene (or SRY gene). This gene is specifically involved in male sexual development.

And sometimes, the SRY gene wanders off to make new friends.

Other times, it shows up fashionably late to the party, or knocks on the “wrong” door.

And still other times, SRY decides not to show up at all.

This, of course, has consequences. If, for instance, SRY decides to share a person’s X chromosome rather than their Y, that human would be physically male, chromosomally female, and genetically male. Additional variants relating to SRY can lead to higher or lower sex-related hormone production or reception.

Even within otherwise decisively female and male categorizations, some females may produce substantially higher levels of male hormones. Similarly, males may produce exponentially higher levels of estrogen.

That’s right: your chromosomal sex has no obligation to match your physical sex, which means that there are XY chromosomed humans who have functional ovaries and can reproduce. There are XX chromosome humans with healthy – or even above average – sperm counts.

And once we move past the chromosomes themselves, the ripple effect causes different responses in each individual. Variations in hormone levels trigger different responses in separate areas of the brain. On some levels, we are faced with examples of this daily – it seems to be the context in which the scenario is presented that provides conflict.

For instance, I would struggle to find someone who deemed an infertile, female-identifying person as being classified a male based on her inability to birth a child.

If, however, I said that a male-identifying person was with child, I would only have to open the local news’ stations comment section to see a wealth of…shall we say, unpalatable opinions on the matter.

Science is not emotional. Our response to science is emotional. When something we held to be a concrete truth is altered, it leaves a sense of missing gravity.

A person who falls between the two pillars of male and female does not simply awaken and "decide" to be differently gendered. Their brain produces chemical, emotional and physical responses differently than their assigned gender. This is not the “invention” of anything new. This is only delayed acknowledgement of research and experience as old as humanity itself.

Imagine this: you’re looking at a range of mountains. From a distance, there are two distinct peaks. You can make a note of this easily and use them as definitive general landmarks. But as you get closer, between – and around – those mountains, there are valleys, hills, and plains, all with their own characteristics. The existence of the mountains does not negate existence of the surrounding landscape.

Previous studies of [human] sex-related topics isolated male and female as defining structures, not least of all because it was simplest. Data graphed using two headers is clean, concise, and easy to digest. What is important to remember is that even within those two categorizations, the variations on genitalia alone are near endless, including size, shape, external and internal features. Yet in Western culture specifically, even these variants somehow rarely presented in an educational environment, leaving individuals not structured like textbook anatomy charts to believe they are in some way abnormal (and often too embarrassed to ask).

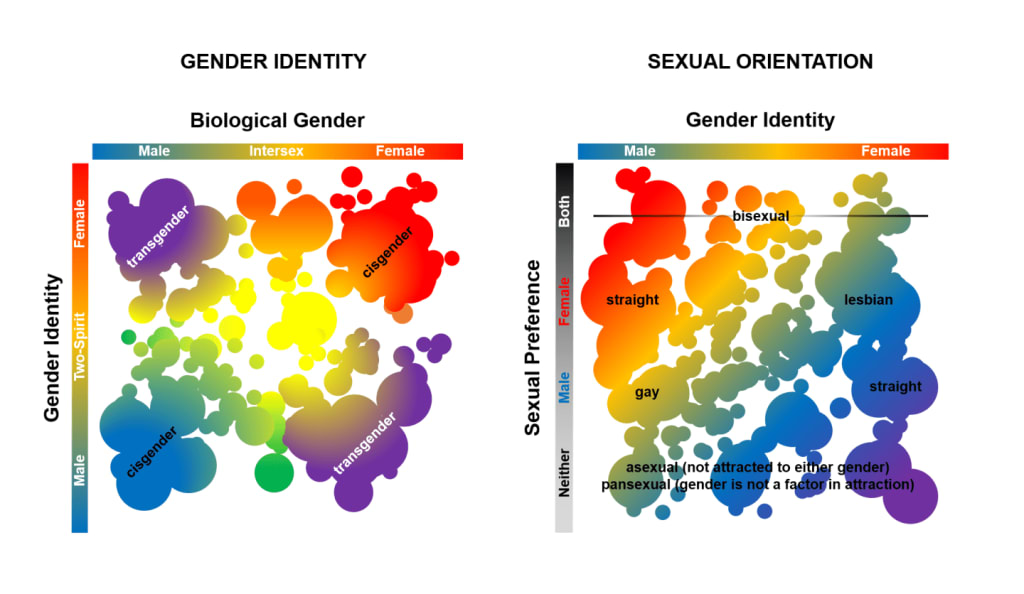

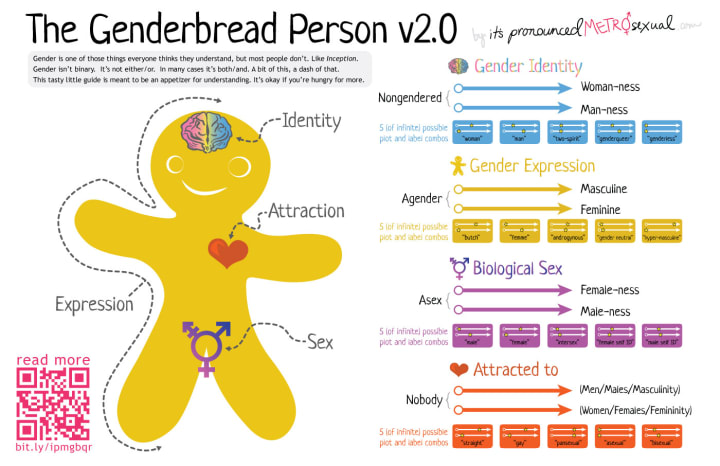

Culturally, we have been led to believe that when these variations occur visibly (as with some intersex individuals) or cause a sense of dysmorphia and the desire to alter one’s physical self to match the brain’s responses (as with some transgender individuals), this is an abnormality. In actuality, we have simply been using broad categorization for so long without regard to the resulting complications, and discounting the wealth of other species that also demonstrate gender fluidity. With the rapid broadening of advances in science and medicine, however, it is not only desirable, but necessary to recognize the importance of individualized needs versus a generalized approach. Biological sex itself is only one portion of the gender spectrum as a whole, which also includes gender identity (how one psychologically views oneself) and gender expression (one's outward expression of gender or androgyny).

And none of this even begins to touch on sexual preferences!

In turn, we must remember that science by definition is always evolving, and that society as a whole struggles to stay up to date. In the early 1900s, cocaine was hailed as a miracle drug. Throughout the 20th century, cigarettes were endorsed by doctors and dentists as beneficial for “improving digestion” and “maintaining slender figures”. When research revealed the detrimental factors of these substances, the public largely dismissed it.

Small wonder, then, that after generations of unconsciously absorbing targeted, gender-specific advertising, products, and entertainment, we have accepted the definitions of our male or female identities as concrete. In most public schools in the US today, sexual education has been limited or removed from the curriculum entirely, leaving little room for early exposure to the updated science.

None of this in any way justifies the dehumanization of our peers. Our delay in acknowleding and accepting this science causes active harm to members of our communities.

Demanding others conform to what makes us comfortable continues to cause societal rifts ranging from mismanaged medical complications to the constant potential of hate crimes. It is especially true while we raise a new generation of children, who - for the first time in memory - have the opportunity to grow up undefined by unconscious gender bias, by pink or blue color coding, unthreatened by their peers’ neutral pronouns.

Perhaps, with time, these children will manage something we struggle with as their mentors – the ability to see others simply as human.

All of this is only a very brief explanation of physical sex, one that honestly fails to even scratch the surface of sexual preference, gender identity, and human development. If you’re confused – good. Questioning your beliefs is important: questioning the things you hold to be undeniably true, perhaps most of all.

And if you’re uncomfortable – great! Science doesn’t ask - or often allow - us to remain comfortable. Continually questioning what we "know" while seeking out valid research allows us to achieve better understanding of both ourselves and each other.

At the end of the day, few things in life can be defined simply by just two pillars -- perhaps least of all human beings. To quote Bill Nye, “Science is the process by which we understand nature, by which we understand our place in the world, how we all fit in.”

Let’s return, briefly, to the potato no longer known as Mister. Not only is the potato (mercifully) lacking genitalia in the first place, the potato is plastic. What has actually been removed is simply the assumption that one must fit a limited criteria in order to exist as oneself.

Now go on. Get out there and respect each other’s pronouns.

-

Further reading:

"Visualizing Sex On a Spectrum", Scientific American, 2017

"Between Gender Lines", Harvard University, 2016

About the Creator

Laura Presley

Laura Presley is a firm believer that magic is real and birds are not. She lives and works in Ohio with her husband, their brood of wildlings, and their excessive number of rescue animals.

IG: @makeshift.martha

Enjoyed the story? Support the Creator.

Subscribe for free to receive all their stories in your feed. You could also pledge your support or give them a one-off tip, letting them know you appreciate their work.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.