LONDON’S VILE VICTORIAN BABY FARMERS

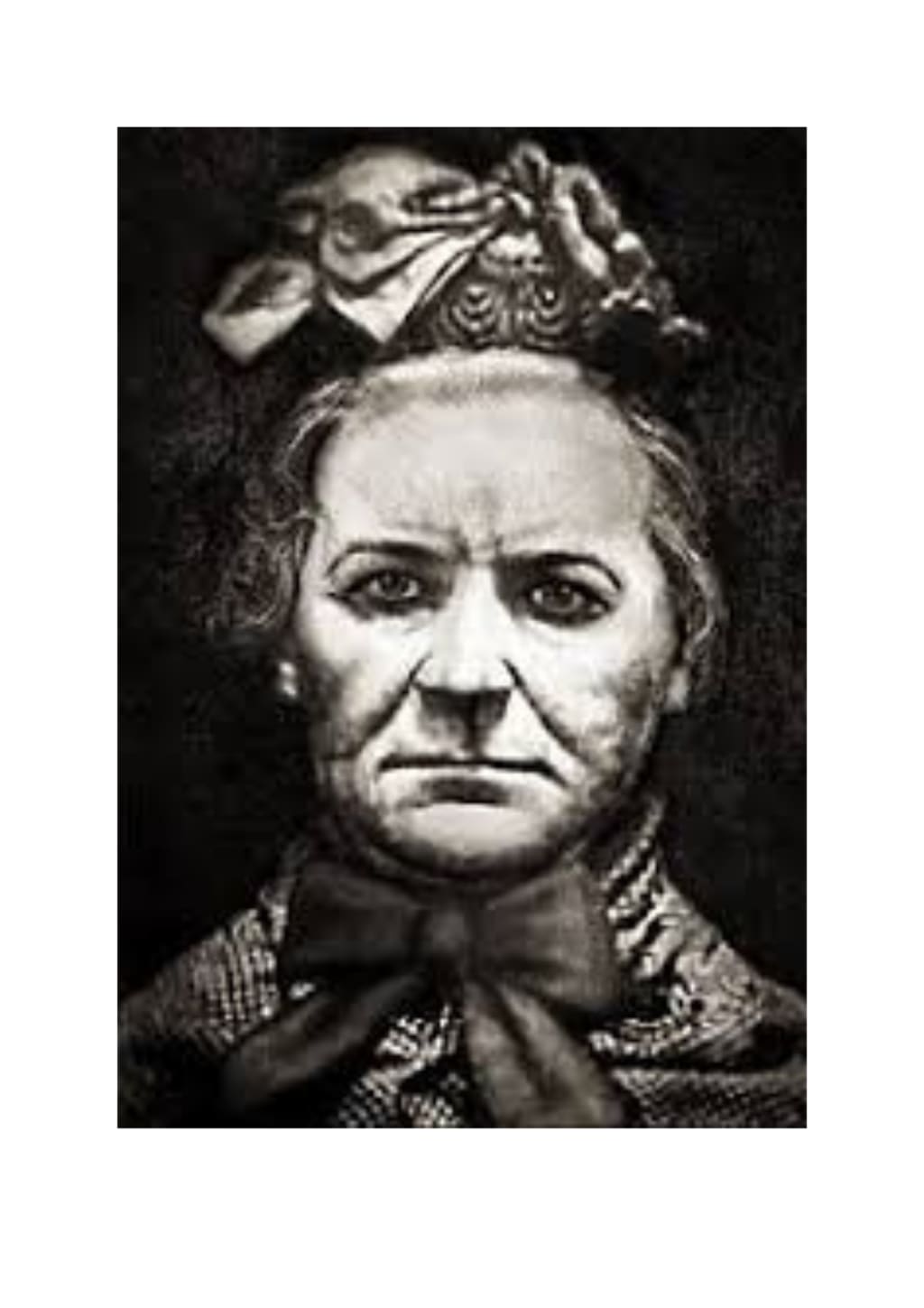

When she was asked how to identify her victims, she said, ‘You’ll know mine by the tape around their necks.’

In the days when it was considered a disgrace to have a child out of marriage, unmarried mothers would regularly pay an older woman to raise their child. In lots of cases, the mother would have no further contact with the child. This permitted some dreadful crimes to be committed by evil baby farmers.

The infamous Margaret Waters was the perpetrator of a little-known crime in the modern age: baby farming. Baby farming in the Victorian era involved paying a surrogate mother to take care of a child under a casual adoption agreement. Money given to the surrogate was almost always not enough to support the child; therefore, it was more profitable for the surrogate to pocket the money and let the child die rather than provide care.

The Brixton baby farmers Margaret Waters and Sarah Ellis killed at least nineteen babies in the 1860s, mainly through starvation. Also, to keep the babies docile and untroublesome during starvation, Waters used tiny amounts of laudanum, which also had the effect of suppressing the child’s appetite.

Waters, who lived in Brixton, placed adverts in local newspapers headed ‘Adoption’ claiming that a married couple in a suitable position were wishing to adopt a baby. A fee was to be payable. She put in twenty-seven adverts in various local papers.

The sixteen-year-old daughter of the Cowen family had become pregnant, and her father answered one advert. He received a letter signed just M. Willis and arranged a meeting with this person he later identified as Margaret Waters. He paid Waters £2 to take his daughter’s baby, John, who had been born on the 14th of May, 1870.

Sergeant Richard Relf of the Metropolitan Police became the first person to specialise in investigating baby farming murders. He examined the cases of 18 infant deaths in the Brixton area. In June 1870, Sergeant Relf spotted another advert for adoption in the same local paper, placed by a Mrs Oliver. He interviewed Mrs Oliver, who turned out to be Margret Waters sister, Sarah Ellis.

After following Ellis to a house in Frederick Terrace the next morning, accompanied by Mr Cowen, they went to the house. They discovered little John Cowen along with five other infants, all in a terrible condition. John should have weighed about 12 lbs, but in fact, he weighed under 6 lbs. On a table, Sergeant Relf found a bottle of laudanum. They removed all the infants from the workhouse, but they all died because of malnutrition and laudanum ingestion.

They tried Margaret Waters and her sister Sarah Ellis at the Old Bailey before the Lord Chief Baron over three days, beginning on the 21st of September 1870. They convicted Waters of the murder of baby John Walter Cowen, for which they sentenced her to death. Sarah Ellis was acquitted of the murders at the direction of the judge but was convicted of taking money under false pretences. She was jailed for eighteen months with hard labour.

Margaret Waters confessed a Dr Edmunds in the condemned cell a few days before they hung her. Her execution was carried out by William Calcraft in a yard within Horsemonger Lane Goal at 9.00 a.m., close to present-day Newington Causeway, Southwark, on Tuesday, the 11th of October 1870.

They drew the bolt at 9.05 a.m. and despite the short drop, she reportedly died with barely a struggle. Some 300 people watched the black flag hoisted over the prison just after 9.00 a.m. to show that they had carried the sentence out.

It may seem strange in the modern era women would be open to placing their children with these shady characters, but we must remember the stigma of being an unwed mother was much more significant during this period. And the options to resolve an illegitimate child were few.

Unmarried mothers faced more than just social hurdles; if they had been deserted, they had no financial support. Passed in 1834, the New Poor Law’s most famous product was the Victorian workhouse. A common assumption made by Victorian society was that poverty was the product of idleness. Therefore, those in need of relief had to work for it. The law stipulated that those in need of relief that was able-bodied could only receive help if they went to the workhouse. The prospect of entering a workhouse was considered a great humiliation to be avoided at all costs.

Terminating the pregnancy was also not an option for working-class women, as abortion was illegal. And if one sought to have the procedure performed secretly, both costly and frequently deadly. So, it’s not really surprising they took drastic measures to avoid the number of mouths one had to feed or find less honest means of income. Baby farming was an answer to both problems, and the unwed mother became their most common customer.

Another factor allowing baby farmers to ply their trade was the commonness of infanticide during the Victorian years. The crime of infanticide was on the rise in Victorian England. For most of the 1800s, half of the recorded infanticides in the UK took place in London. This was likely because of the massive population and the ease of hiding a crime in a place where a person could be easily overlooked, such as the filthy London slums. Many argued that the rise of infanticide directly resulted from the New Poor Law. As the law limited a woman’s right to seek aid from the child’s father. The only government aid that could be received by an unmarried mother was contingent on her entering a workhouse. Because of this, the death rate for illegitimate infants was twice as high as the mortality of legitimate children.

Another baby farmer, Amelia Dyer, was executed in 1896. She killed infants either through starvation or strangulation with fabric tape. The bodies were then dumped in a canal. It’s not known how many babies she killed, but historians estimate that over the twenty years of her career it could have been at least 50. When she was asked how to identify her victims, she said, ‘You’ll know mine by the tape around their necks.’

About the Creator

Paul Asling

I share a special love for London, both new and old. I began writing fiction at 40, with most of my books and stories set in London.

MY WRITING WILL MAKE YOU LAUGH, CRY, AND HAVE YOU GRIPPED THROUGHOUT.

paulaslingauthor.com

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.