Tsiñu walked down the dark cement hallway. He was the last of the recruits to pass through intake, his head shaved bald, his naked body hosed down. The sting of sterilization powder still clung to his skin underneath the gray jumpsuit. That was the last step—he was now ready for the Laag.

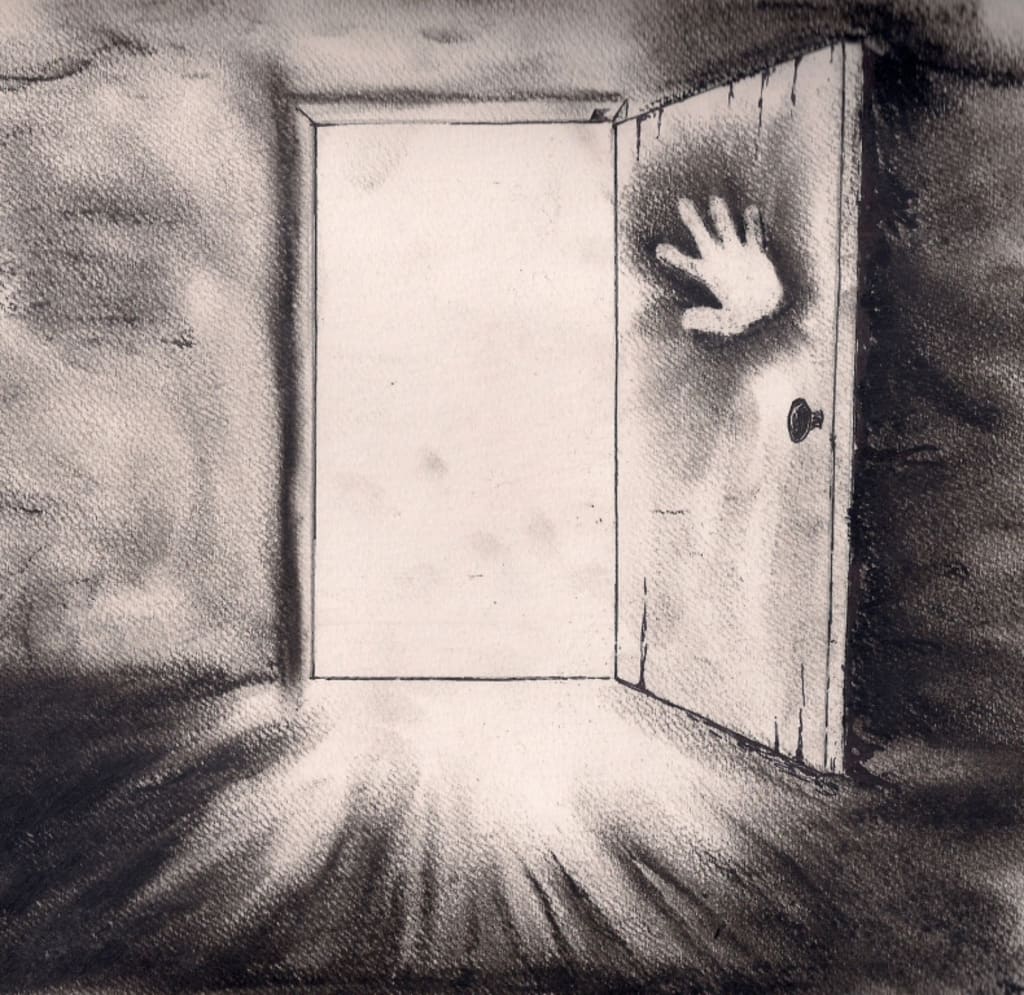

As he left the Processing Center, the long passageway reminded him of some craggy, sinister birth canal. Nobody remembers being in the womb, he thought. Every stage of life is cut off from the one before it, separated perfectly and absolutely. You cross over, and your former life no longer exists.

Womb to birth.

Childhood to Laag.

It’s the same for every human. Once you turn twelve, you enter a different world, a dimension of blood and sweat and hard labor. The comforts of childhood—the pampering, the leisure, the luxury—they no longer exist. Nothing exists but the Laag.

Tsiñu’s feet softly padded down the concrete in their flimsy sandals.

Flip flop, flip flop.

He shuffled behind the resolute pounding of the guard’s boots.

Pam pam. Pam pam.

His sweaty hand clutched his mother’s locket. He felt its irregular, oblong shape, the metallic atria and ventricles, the stubby miniature valves. “Remember, Tsiñu,” she had said as she’d pressed the locket into his hand that morning, “the same heart that beats in your chest now will keep on beating inside the Laag. You are still the same person. They can’t take that from you.”

His father had rarely spoken of his own time inside the labor camp. Nobody ever talked about his missing right eye, and nobody needed to—everyone knew he lost it during his teenage years of service. The Laag was brutal and unforgiving.

In the distance, at the far end of the hallway, Tsiñu heard a low rumble. A murmur, faint yet overwhelming. It was the crowd of other recruits, the Antechamber to the Laag.

The few times that Tsiñu’s father had mentioned his own years of service, it was in general terms. “It’s just three years, son. Then it ends. You come out into the world of adults, you get your cushy job, and you never have to think about the Laag again. It stops being real.”

Tsiñu’s nearly bare feet plodded forward, approaching that growing rumble at the other end of the hallway.

Flip flop, flip flop.

The guard’s black leather boots stomped two paces ahead:

Pam pam. Pam pam.

The dark cement walls dripped tears of black mildew. Even inside this tunnel, the heat was muggy and oppressive. Tsiñu thought back to that morning, when his father had spoken candidly about the Laag for the first time. With cold, calculating eyes, he looked at his son and said, “Whatever happens, make sure you don’t end up at the bottom. The weakest, the slowest, the fattest—those are the ones who get stabbed and beaten. And worse. Some die during their first week.”

Tsiñu tried to focus on the locket, pushing the impending doom out of his mind. In an exercise of dissociation, he thought back to pictures of “hearts” he had seen in history books. Ancient humans had depicted the organ as a bulbous, symmetrical shape that came to a point at the bottom. Ancient humans appeared to have clung to this image all the way into the 23rd century.

What a quaint, simple time. When hearts were nothing but round, smooth objects. When the Laag didn’t yet exist. When humans didn’t enslave their own youth.

Tsiñu’s reverie was broken by the growing rumble at the end of the tunnel. It rose to a roar, louder and louder, a thundering tide of angry youth, like the crashing tsunamis that had swallowed the nation’s coastal cities so many centuries ago.

Before he knew it, Tsiñu was standing before the massive iron door. The guard grabbed his arm. “Before you go in…”

Optimistically, he thought the hulking man was about to give him some words of advice, some paternal tips for surviving the Laag. “Yes, sir?”

Hand it over.” The guard extended a beefy hand. “No trinkets allowed inside.”

Powerless, Tsiñu dropped the heart locket into the man’s hand. His childhood ended in that very instant. He now belonged to the Laag.

The iron door swung open and the guard pushed Tsiñu into the crowd. The roar of voices was deafening as he was jostled forward into a sea of sweaty adolescent bodies, all in gray jumpsuits. Freshly shaven bald heads of different tones surrounded him, the soft, naked, tender scalps of the other new recruits.

The Antechamber of the Laag.

The crowd of twelve-year-old boys was surrounded by dirty cement walls, rising ten meters up to meet the gray steel roof. Mist and dim sunlight drifted in through open holes at the top of the walls. The walls held in the steamy dank heat and the smell of sweat and fear.

A rough pecking order was already emerging in the crowd. Most of the boys shouted at each other with forced bravado, feigning expressions of indifference. Tsiñu struggled to do the same. A few of the recruits looked absolutely horrified, pasty faces and ruby cheeks, visibly trembling in their gray jumpsuits and sandals. If Tsiñu’s father was right, these boys would be the first to fall.

Tsiñu looked at the edges of the crowd and involuntarily shuddered. Those were the recruits that his father had warned him to stay clear of—the scary ones. The brutal boys who had long anticipated the Laag, those who would thrive inside like the black mildew that grew on its concrete walls. Those who had hit puberty before everyone else, whose arms already bulged with fresh muscles. They stood in silence and smiled, arms crossed, relishing in the grime and violence of the place. The message was clear: as soon as everyone was ushered inside, they would be at the top of the pile.

Again, the voice of Tsiñu’s father echoed in head: “Don’t end up at the bottom…” He straightened his posture and steeled his jaw.

Suddenly, the crowd went silent and Tsiñu followed the glances of his fellow recruits. High above their heads, a tall wooden platform jutted out from the cement wall.

There stood the Commandant.

He stared out at the sea of bald heads in silence. His black uniform was freshly pressed and immaculate: pants tucked into leather boots, black gloves on his hands. He folded them over his chest and breathed deeply. At last, he cleared his throat and addressed the crowd.

“You boys have much to be proud of. You will spend the next three years working to sustain our great nation. At this very moment, other boys your age are supporting our homeland in other Laags. In the mines, the factories, the fields and foundries. You now stand among them.”

Tsiñu heard a low, metallic creaking from the wall to his right. He turned slightly and noticed a crack of light running up and down the length of the wall.

“Aeons ago,” the Commandant continued, “in the ancient past, there were no Laags. Primitive societies got their Laag work done in barbaric ways, by creating entire classes of people to do it. Lower castes, foreigners, prisoners, slaves. However, after years of wars and devastation, we have now found a better way. All of us earn our keep in this civilized nation. You boys will help create the prosperity and wellbeing that make us great. Take your place and be proud. Take your place… In the Laag.”

At these words, Tsiñu heard the sound of groaning metal, like the terrible maw of some great beast awaking. The entire wall to the right opened up, two massive doors pulled by human hands. Tsiñu saw the workers hauling the ropes—hardened, scarred, ruthless Third Years, little humanity left in them, all throbbing muscles and dead eyes.

Once the doors lay open, the stench of garbage filled the Antechamber. Over the bald heads around him, Tsiñu caught glimpses of the world beyond: a patch of green-gray sky, crowds of adolescent workers crawling over mountains of trash. The putrid odor of acid rain. In the distance, the occasional scream. Tsiñu’s mounting dread was morphing into abject terror. This was real. This would be his life for the next three years.

He suddenly noticed the other boys slowly edging away from him. The empty circle around him grew wider, amidst smiles and snickers. A couple of the recruits pointed. He looked down.

Oh, no…

He felt the warmth slowly spreading between his legs.

No, no, no…

A dark stain grew on the crotch of his gray jumpsuit.

Please, God, no…

At the edge of the crowd, the tall boys leaning against the wall smirked. They exchanged knowing glances.

The worst had happened. He would never recover from this. No matter what he did, Tsiñu was now one of them—the weak ones. The worst part was, whatever happened inside, nobody on the outside would see it. This was a black hole, invisible to all who lived in the peaceful, prosperous, civilized world outside.

And the Laag was about to eat Tsiñu alive.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.