H.J. Eysenck Interview

Dr. H.J. Eysenck discusses psychology, public issues, and the human potential of his scientific approach.

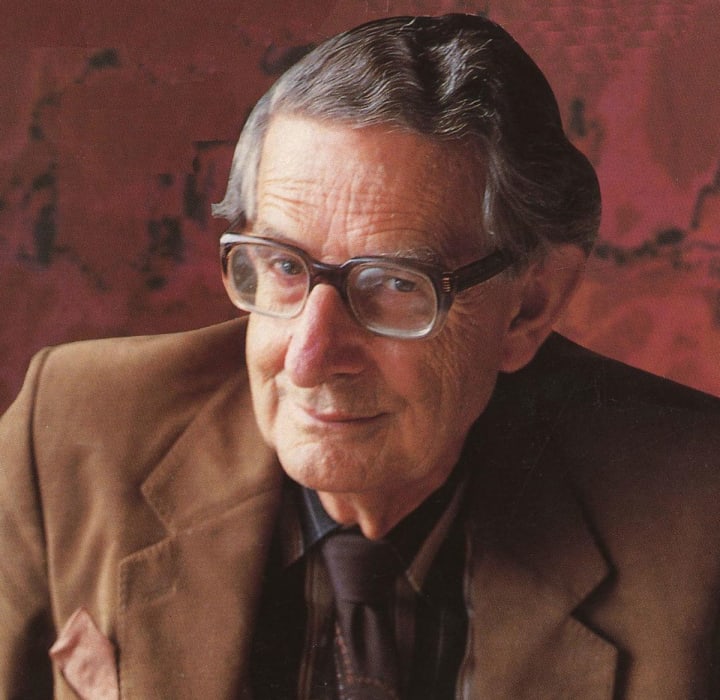

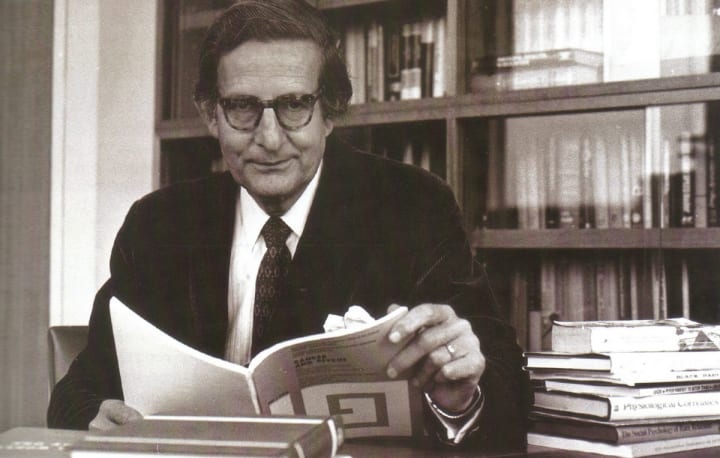

A psychologist with an international reputation, both as author and as a leader of the behaviorist school, Professor Hans Jurgen Eysenck was director of the Institute of Psychiatry at London's Maudsley hospital. A prolific popularizer, he wrote more than a dozen books expounding aspects of his absorbing subject (Uses and Abuses of Psychology, etc.) and he is particularly remembered for his paperbacks of intelligence tests. To professional colleagues, he is an eloquent repudiator of Freud and an indefatigable researcher into the mechanics of personality.

Dr. Eysenck was German-born, and transferred to London University in the 1930s. He went intending to take up research physics, but chose the wrong qualifying subjects for his entrance examination. Rather than wait a year for another try, he asked if there was any other science subject he could take with his German qualifications and was told he could do psychology. "What's psychology?" he asked. "You'll like it," they told him, and he did. In this exclusive vintage Penthouse interview conducted by David Cohen, Dr. Eysenck discussed psychology in relation to various contemporary public issues, and explained the human potential of his scientific approach.

David Cohen: Professor Eysenck, you have gained the reputation, unusual in a psychologist, of being skeptical and hard-headed. Is that how you would wish to be thought of?

H.J. Eysenck: I don't easily believe in things unless they are demonstrated experimentally and I see some factual support for them. That's why I don't believe much in psychoanalysis and things of that kind—not because I don't want to believe but simply because the necessary experiments to prove it haven't been done, and not even the necessary clinical trial to show it is effective. Until that is done I am skeptical. If that's what you mean by hard-headed—yes, I don't dispute it.

Do you think there are any limits to what can be discovered by experiment?

That's a very difficult question. In principle, I agree with Thorndike, who once said that everything that exists, exists in some quantity and can therefore be measured. Therefore anything that has a real existence in any sense of that term is subject to scientific discovery and can be discovered. So on the whole I would probably say yes to that.

But can you conceive of cases where it's so difficult to construct experiments and differentiate things that it may be impractical?

I think it is always foolish for a scientist to say that something is impossible. You probably know the famous story of Johannes Muller, the great German physiologist of the last century who in 1850 wrote in his textbook that it would be forever impossible to measure the speed of the nervous impulse because it was too fast. But three years later Helmholtz actually measured it, so I wouldn't like to stick my neck out and say anything was impossible for practical and similar reasons. They always will be overcoming these difficulties and finding out what you want to find out.

Do you have any room for a concept like the soul or the old Cartesian mind?

Well, I feel about it rather like the German poet Heine did when somebody asked him about the existence of God. He said: "C'est une hypothese dont je n'ai pas besoin" (It's a hypothesis I don't need). Maybe in due course we will need it, but at the moment we can do without it. So, strictly from the scientific point of view—no, I don't.

You favor an experimental society in which much greater knowledge is deliberately pursued. In what ways would such knowledge affect the way we live?

A simple example is comprehensive schools. In Britain now the Labour Party is very much in favor of them. The Conservative Party is rather opposed to the complete introduction of them and wants because in Germany all schools were comprehensive (as in the US) but the effect of these schools was hardly very good, was it? They led to Hitler and all sorts of other evils, not by themselves of course—there were other causes, too. Certainly there was no tendency in the schools for working-class and middle-class children to mingle more freely than they do in this country. They tended to keep to themselves. Now I am not saying this would necessarily happen here; I am just saying that nobody really knows and before you introduce such a far-reaching innovation you ought to find out. You ought to do some experiments to see what actually happens. And after you have introduced it you should go on doing experimental work to see if the thing is actually working. That's what I mean. Most political innovations are argued about not in factual terms but in terms of some sort of preconception. That is one example.

There are many others, like the treatment of criminals. One always hopes to rehabilitate criminals but all the argument about it doesn't give us any facts. People say you should be tougher on them or you should be less tough, but there are no facts whatsoever to back up these things. Therefore the need is obviously for research.

Photo via The Conversation

You have noted in your book Crime and Personality certain connections between criminality and various physiological characteristics.

Yes, there are rather indirect associations. There is first of all the finding that criminality seems to be to some extent inherited. In other words, inherited physiological structures within the organism predispose a person to crime on coming in contact with certain types of environments. What intrigued me was to find out what these structures were and so we did a certain amount of work which suggests that essentially it is part of the so called reticular formation which is a part of the brain stem responsible for maintaining a high state of arousal in the cortex. In the potential criminal, this doesn't work very well, and his brain is in a state of low arousal. This in turn makes it more difficult for him to become conditioned and learn the kind of social habits which constitute what we call socialization. Therefore, he is effectively without a conscience, because that is the end-product of the socialization process. So to think of such a criminal as being responsible in a free-will kind of way is rather absurd. He is a product of his heredity and of the kind of environment he encounters and therefore one should base one's strategy on these ascertained facts rather than punish him.

What kinds of strategy, what kind of cure does your research lead you to suggest?

If a criminal behaves criminally largely because he has failed to become properly conditioned and to become aware of the system of contingency on which society operates—that is, do the right thing and you are rewarded, and do the wrong thing and you are punished—the obvious method is to put him through a process of conditioning which emphasizes these things. Some work has recently been done in the States which suggests that this is indeed successful. It is not yet far enough advanced, because there has not been enough time to do the follow-up studies, but it has been successful in making the criminal and juvenile delinquents, on whom it was tried, much more law-abiding, much more responsive to social stimuli. It is to be hoped that they will remain that way when they're followed up—when they're out of prison or out of reformatory or wherever it is.

Does the same failure to condition apply to disturbed people?

Not necessarily, not usually. It's generally the other way around: People suffering from anxiety neurosis and phobias and obsessional and compulsive disturbances are ones who have been conditioned, only too well. They're at the opposite end. Their reticular formation produces a high state of arousal and extremely good conditioning, and therefore they condition fears and anxieties and so on to stimuli which, in a normal person, would not produce such conditioning at all. So if anything, they err in the opposite direction, they're hyper-sensitive to conditioning and therefore suffer from these conditioned fears.

You're involved in a new kind of therapy in this area, aren't you?

That's right. It's called behavior therapy, in which we try to desensitize these acquired or conditioned fears and extinguish them. It seems to work very well.

Can you explain how it works?

Essentially, what we do is to take a person who is afraid of a certain object, certain ideas, or class of object, or whatever it is—say a cat. This fear is of course unreasonable, but reasoning with the patient about it doesn't help because he knows perfectly well that it is unreasonable. He just can't get over it. What we do is to try and get him into as calm and relaxed a state of mind as possible and then present him with a small replica, as it were, of the fear-producing stimulus, situation, or object—say a picture of a cat shown at a distance.

Well, this produces a small amount of anxiety but not enough to really upset him. As he can see that he can tolerate this quite well in his relaxed state, he is ready for a slightly larger picture, brought slightly nearer. Eventually he is able to tolerate a small cat at a distance, a larger cat, and so on, brought nearer and nearer until finally he is ready to actually touch a cat. This is of course oversimplified, but in essence you build up a hierarchy of fear-producing stimuli from the least to the most and then you work through it, always relaxing him, and reassuring him as you go up this ladder.

Photo via RenMuChal

And are the effects lasting outside the laboratory?

Fortunately, yes.

You have dismissed psychoanalysis and you are also on record as rejecting Ronald Laing's work on schizophrenics.

That's right. These treatments are unconvincing for a number of reasons. In the first place, practically all disorders remit spontaneously. In other words, people get better for no obvious reason. Therefore, if you want to show that a given therapy works you have to compare the percentage of recovery with the percentage of recovery of the group to retain grammar schools and so on. Both parties argue about this but neither party has any of the facts necessary to a proper decision. There are all sorts of assumptions: that a comprehensive school will benefit the duller ones by bringing them in contact with the brighter ones, that it will reduce social class feelings, and so on. That's all possible, but there's no evidence whatsoever and things may in fact work the other way. I went to a comprehensive school who haven't been treated, or have been treated in some other way which you consider inferior. This, of course, Laing and Cooper and the others have never done. Until it is done what can one say? They treat a small number of atypical schizophrenics, some of whom get better and some don't. No accurate statistics are presented, and in any case the sample is too small to give much in the way of statistics. Some of these people would have gotten better if they hadn't been treated at all. Why should I be convinced by statements that they're doing some good to these people when there is no real evidence for it?

In the book The Family of Schizophrenics they seemed to depict a persuasive causation of schizophrenia.

It is easy to draw persuasive pictures. The difficulty is to produce experimental evidence that will convince somebody who doesn't necessarily believe this. Furthermore they neglect the strong evidence of heredity. Identical twins are much more alike with respect to schizophrenic breakdown than are fraternal twins that don't share 100 percent heredity. This you cannot explain in terms of such simple schemes as they produce. I'm not saying that what they say is necessarily false; I am simply saying that the evidence is quite inconclusive. It's a pretty picture, but whether it's accurate or not nobody can say, and until some thorough research is done I don't think one can accept it.

Do you still think the whole movement of psychoanalysis has delayed the progress of psychiatry?

I do. I think it has taken 50 years out of psychiatry which could have been devoted to proper research. Instead it has been devoted to speculation and relatively arid attempts at treatment, which were not successful and are now pretty universally regarded as not successful. We could have done a lot in this time.

Why do you think the Freud school was such an all-pervasive movement?

Probably because psychiatry previous to Freud tended to be rather academic and not treatment-centered. Madness, psychosis, neurosis, and so on, were seen as things about which you could do very little, and so they concentrated on describing it, studying it, perhaps even experimenting with it, but not attempting to cure it. Freud, with all his faults, certainly was concerned with treatment, and he held out the possibility of treating people successfully. It didn't work but it is difficult to blame him for trying, and I wouldn't do that, of course. He attracted people who were more concerned with treatment than with the academic concerns of the psychiatrists who preceded him.

Furthermore, of course, I would say that Freud was a brilliant novelist. He wrote fairy tales which are very attractive to people who are not brought up in a scientific tradition but in a humanistic tradition. It is good literature. I'm sure he deserved the Goethe prize he won, which is normally given to novelists. He is a very good writer—a great writer in fact. If you like that kind of thing you enjoy reading it, and I enjoy it too, but as writing, not as science.

Photo via The Famous People

As a student of psychology do you have any explanation of the sexual experimentation and upsurge of permissiveness that seems to be a feature of our times?

I think this permissiveness is much less than is commonly said. I did a study recently in which we questioned large numbers of university students about their sexual experiences and attitudes. What came out clearly was that if you take girls of eighteen or nineteen, only about one in five have in fact had intercourse. This figure is probably not at all different to what would have been true 30 or 40 years ago. In fact, it agrees well with Kinsey's work and with others who worked in between times. So I doubt if there has been that much of a change. I think the permissiveness we talk about is largely an invention of the newspapers, of the television, and of the films. People can see that they can earn money from putting pornography on the screen and in the papers and they do so. And they do it under the pretext that this is a modern swinging generation. In reality the modern swinging generation isn't like that at all, and if you look into it you find that young people are much as they were before. I think the evidence suggests strongly that if you take, say, the number of girls who are still virgins at the ages of eighteen or nineteen or twenty as an index of unswingingness ,then 100 years ago you would have found far fewer virgins than you do now, certainly in the working-class groups. The picture we have of Victorian society as very restricted is misleading. The Victorian stereotype is true of a minute proportion of the population—what one might call the upper middle classes, and perhaps even the lower middle classes—but the much larger working class was nothing like that. They were extremely permissive, and the estimate is that few girls in their class would have retained their virginity anything like as long as they do now. I don't believe all this permissiveness. I think that when all is said and done, more is said than done.

Another form of permissiveness is drug-taking. Do you see any merit in the cult of experimenting with drugs?

None at all. I think this is an extremely dangerous thing. I think it is extremely inadvisable, because people who play with drugs are playing with fire and are liable to kill themselves in a very short period of time. This is not a thing one ought to feel easy about. I don't even feel easy about alcohol and tobacco. I think they kill far more people than almost anything else in our present society and now we extend the scope to drugs, many of which are much more dangerous even. I think it's a foolishness that is almost incomprehensible.

You wouldn't agree, then, that there is some force to the arguments for legalizing cannabis?

I think cannabis is perhaps the least dangerous of these drugs. The argument is essentially whether legalizing it would reduce its attraction to many people who are attracted by what is forbidden. I'm not really convinced that it would, but I'm not an expert in this field. I wouldn't like to say.

You mentioned feeling uneasy about tobacco smoking. Do you accept that this habit is the direct cause of lung cancer?

I think there is certainly a connection but it's very much oversimplifying to say that lung cancer is caused by smoking. Of all the people who get lung cancer, one in 10 doesn't smoke at all, and of all the people who do smoke, only one in 10 get lung cancer.

What about stress as the common factor?

Well, people who are highly neurotic seem to be protected against cancer, so it's just the other way round. They develop lung cancer very little by comparison with those who are very stable. This has been shown several times and seems to be an established fact. Possibly neurotic people, with their high secretion rate of adrenaline and so on, may secrete a substance that protects them, some kind of hormone that acts against cancer. Some work on this point is being done now with rats, but it's rather technical.

Photo via Like Success

Hasn't it always been thought that heavy smokers are neurotic?

Everyone says this but it's just speculation. There's no real evidence to show that people who smoke a lot are neurotic. What evidence there is suggests people may smoke out of boredom as much as out of stress. As I pointed out in my book on smoking and cancer, not enough research has been done on this whole question. What research has been done has been so inept and inadequate that it's difficult to base a conclusion on it.

If as a race we get to know more psychology and use it more, how do you think it could affect human life, say, 25 years from now?

The change would almost certainly be for the better, for very simple reasons. I have a strong feeling that most of our problems are psychological ones. We know enough science—that is, physics and chemistry—for most of the things that we need. We are getting to know enough biology for most of the things that we really want to know. There are a few items that we'd like to know about—the origin of cancer and so on—but by and large we do know quite a lot. Our problems are problems of human interaction—hostility, aggressiveness, war, strikes, all that kind of thing. These are largely psychological problems and they cannot be solved, and I want to emphasize this, by well meaning political or social attitudes or reliefs—anything of that kind. I have the highest respect for what are sometimes called "do-gooders," who obviously have a motivation to do the right thing, which is admirable. They often suffer greatly, financially and in other ways, for what they are doing, but action taken in ignorance is always dangerous and until we know just what it is that we need to do I think do-gooding is really essentially impossible.

Let me give you a simple example of what have in mind. There exists a class of children who bang their heads and injure themselves. They may bang their heads so harshly and sharply that their retinae become detached, they become blind, they may even kill themselves. This is clearly a very serious condition. Traditionally these children have been restrained; They are tied up, because that is all you can do. Then came the psychoanalytic notion that they're searching for attention and want to be loved, so whenever they get into one of their fits, kiss them, love them, embrace them, be kind to them, and so on. This is just what your typical do-gooder would consider a reasonable, rational thing to do, but what's wrong with it is simply that it makes the children worse. This has been established over and over again. We have now worked out a technique for dealing with this kind of child. The moment he starts banging his head, pick him up, take him to a bare room, lock him in for 15 minutes without any show of anger, annoyance, anything else. This is a simple consequence—if he does that he is isolated for 15 minutes. Then you take him out again and treat him as if nothing had happened. In a large number of cases, this has worked extremely well, and within only two or three weeks. The child stops banging his head because the behavior isn't reinforced—it isn't being rewarded. You see what a typical psychoanalytic treatment is: he does the wrong thing and then he is rewarded for it with kindness, kisses, attention. Thus, do-gooding is exactly the wrong thing—it produces the opposite to what you want, like the chap who tries to train his dog to come when he whistles. He whistles and the dog doesn't come, he gets annoyed, and finally when the dog comes he beats it. In other words, the dog comes and is beaten so naturally he doesn't come again. This is doing exactly the wrong thing for his own reasons. The do-gooder wants to be kind but it isn't appropriate in the situation. The man with the dog is annoyed and wants to punish somebody, but it isn't appropriate in that situation. The choice is between doing what is functional, what achieves what you want to accomplish, and giving way to your own emotions.

What psychology is trying to do is to establish what is functional in a given situation and therefore I think that if progress continues over the next 25 or 30 years, we'll know a great deal more about what is functional. Education—to go back to that example—hasn't improved at all over the last 2,000 years. We do exactly the same now as we did then. If we knew how to get children interested in their school work, it would be a milestone in the development of a proper educational system. But, of course, we don't, and we don't do the research that is needed to find it out. That is my great objection to our present way of doing things. We argue about political things, like comprehensive education, while the same bored children sit there exposed to the same boring old lectures. This is what ought to be changed. The comprehensive and incomprehensible nature is probably quite irrelevant to anything that anybody is really interested in. It's a political football, that's all.

So you would hope to see a political attitude based on a scientific approach, rather than on dogmatic isms?

Yes, we need to make our society an experimental one, not one that is based on superstition, on all sorts of political beliefs which are unsubstantiated. It should be functional, first of all looking at what should be done, deciding what it wants and then doing the research to indicate how it could achieve that end. Since most of these problems are psychological most of the research will have to be psychological.

Professor Eysenck, thank you.

About the Creator

Filthy Staff

A group of inappropriate, unconventional & disruptive professionals. Some are women, some are men, some are straight, some are gay. All are Filthy.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.