He was not quite twenty-four when he fell in love with the girl from over the fence. Although he had only spoken to her four times in the eight months they had been neighbours, it was enough to steal his heart.

Her features were rounded and her short, black, hair curled behind her ears. She had a missing top molar when she smiled but it was endearing. Her name was Rasia and her family had originally come from Russia, in the twenties. She spoke with a slight accent still and her sibilant consonants whistled through the gap in her teeth. She had wanted to be a violinist but her teacher had said she lacked the necessary dexterity. Isaac thought her thin hands looked like they could do anything.

Her favourite flowers were marigolds. She had a book of flower pressings in her last home but not managed to take it with her. It was the first thing she told him. (All her stories came out of sequence. He liked that about her).

Every day, Isaac scoured the terrain for marigolds, but to no avail. Mind you, it was still winter, he thought. Perhaps there would be some in the spring.

As he cast his eyes over the hard ground, pulling his burden behind him, he thought how this freedom could not be taken from him.

“Schnell!” barked the guard, and Isaac doubled his pace, snagging the wheel of the wagon on a stone. His partner steadied it and they made it to their destination without taking a beating.

“What were you doing, staring at the ground?” asked his partner as they drank their soup. He had only been assigned to him today and this was the first time they had had a chance to communicate beyond the necessary instructions for loading, transporting, and unloading their cart.

“I was looking for marigolds,” he said, and licked around the edges of his bowl.

“Whatever for?”

“Not a what – a whom.” Isaac’s eyes twinkled, slightly. Before his internment they had been a dazzling blue. Now, they seemed greyer.

His partner was intrigued, and Isaac delighted in telling him all about Rasia – embellishing some details here and there as he romanticised.

“Well, I’m sorry to burst your bubble, my friend, but I don’t think marigolds are indigenous to this area.”

“You never know.”

“Well, you do if you know anything about botany. I happen to have been studying it right before – well, you know.”

“Yes.”

Their conversation dwindled. Isaac had been in the camp long enough to know that some people couldn’t cope with thinking about life outside of it – whilst others practically lived beyond the fence in their imagination. Each man had his own way of coping with their situation, and must be allowed to indulge it.

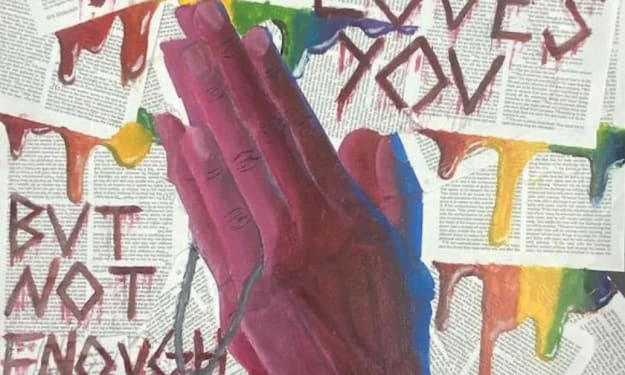

Isaac had love, and the faith of his ancestors to fall back on. Before the War, he would not have described himself as devout. He kept the traditions for their own sake (and because, as the first-born, it was expected). Here, in Birkenau, he had time to reflect, and oscillated between moments of apostacy, and extreme piety. It was, he thought, a good way to punish the Nazis – who seemed to hate them merely because of their descendance from Abraham. If they wished to get rid of them all, it was a duty – and an act of rebellion – to cling on to the rituals, and to pray (as much as anyone could in such circumstances). Perhaps there was no God to hear but there were other men; there were their enemies.

He hurriedly said bracha for his soup, (despite having finished it) and added, in his mind, a prayer for him to be able to give Rasia a marigold.

The respite was over; he and his compatriot returned to work.

Spring broke through but no marigolds. Occasionally there were some wildflowers – yellow and white, but soon trampled under the foot of a clog or boot.

The work got harder and, as Isaac loaded the sawdust and bodies onto the wagon, he began to feel more like the dust and less like a human body. It would only be a matter of time until his replacement was loading him on to this same wagon.

Perhaps . . . he thought, looking from the chimneys to the fence, and back to the wagon, perhaps it would save a lot of bother if I just climbed in, now. He looked at the faces of his anonymous siblings in the wagon who no longer suffered, or feared, or hungered. Or hoped, he thought. Had he given up on hope? His spirit seemed as weak as his body. He was truly, now, a muselmann – a living skeleton. He would not make it through another selection. He might not make it through the night.

He raised a leg as if to climb into the wagon but even that would take too much effort.

Easier to keep pulling it.

That night, as he queued for his bread ration, Isaac could feel the vultures circling overhead – in the shadows of the kapos, in the cruelty of the guards, in the desperate misery of his fellows, hoping he would die with a crust in his hand so they could take it from him.

He tried to stretch out his hand to take his portion but found his hand wouldn’t obey him.

A younger hand came from behind and took it. Isaac resigned himself to the fact – indeed, he was expecting it. He would be dead, soon.

It was to his greatest surprise, then, when he felt the strong hand thrusting the loaf into his own and walking him over to a corner where he sat him down.

Isaac looked up at his benefactor. He couldn’t have been much older than seventeen or eighteen. His triangle was red – a political prisoner, and German, by the lack of country’s letters embroidered on it. He had a scar on his cheek but looked in good shape, otherwise. When he spoke, to ask Isaac’s name, it had a softness to it, and an accent which he didn’t quite recognise.

“I’m Christof,” he said, in response to Isaac’s introduction. “Here, let me fetch you some water.”

Isaac thought he gone mad. Water was not easily come by – the kitchen rarely handed it out and it was hardly worth trying to court a favour on his behalf. Before he could protest, Christof dived into his uniform and brought out a hip flask which he handed over.

The cap was screwed on too tightly and Christof had to undo it for Isaac. There wasn’t much left, so he just used it to wet his lips and take a single sip.

“Thank you,” said Isaac, handing it back. “I’m sorry, I haven’t anything to give you.”

“I don’t want anything. Just to help.”

The words were kind, thought Isaac, but stupid. It was pointless to waste compassion on him – let alone resources. He would be dead, soon. He told Christof as much.

“Not if I can help it,” he said, and tore off a piece of his own bread to feed Isaac.

Isaac regarded him for a moment, unsure as to whether to accept it, or whether he could be trusted. He saw kindness in his eyes. He took the bread.

“What kommando are you in?”

“The Rollwagen.”

“That must be a lot of heavy lifting.”

“So heavy!”

Isaac nibbled the crust – chewing was an effort.

“I’ll see if I can call in a favour,” said Christof, as if talking to an old friend from school. “Err, do you have any skills?”

“Not really,” said Isaac, a little crestfallen, before adding that he used to do a little sewing for his father – who ran a shop before the War.

“I’ll do my best. Tomorrow’s Sunday, fortunately, so you have that off and I’ll hope to have good news for you by the evening. Here, drink up.” He passed the flask back to Isaac and insisted on his drinking the last of it.

If he died that night, thought Isaac, he would die with his faith in humanity restored.

But Isaac did not die that night, and Christof returned the next evening with some good news:

“I’ve got you a gig in the Kanada!”

It was, relatively speaking, an easy kommando: sorting through the possessions of the arrivals, occasionally patching up some uniforms for the Nazis. Isaac had not been skilled with a needle but he was a quick study. Being indoors certainly helped, and Christof gave him a portion of his own bread every evening. They didn’t talk much: Christof was in the camp band. To his shame, Isaac admitted that he used to spit at the band each morning as they played them out to work. The marches seemed inappropriately cheerful, and they were often too fast – especially at the end of a hard day’s work. Now, Isaac understood that the bandmembers were simply doing the same as everyone else: whatever it took to survive.

Gradually, Isaac’s strength returned and, with it, the light in his eyes. He had managed to procure some yellow thread and had been sewing a marigold onto a piece of white cloth. It had taken him several weeks and cost him a few cigarettes (which he had managed to smuggle under his cap when he came across them in suitcases), but it was worth it.

Now he just needed to find Rasia and give it to her.

As he stood in the queue for soup one August evening, Christof dropped his bowl and Isaac caught it with the lightning reflexes of his boyhood. “I don’t need your bread tonight,” he said, handing him the bowl. Christof beamed and shook his hand vigorously.

“I’m so glad,” he said, and then faltered, is if he were worried he was coming across as being mercenary.

“I mean . . . ”

“I know,” said Isaac. “I am glad, too, my friend. You saved my life with your patience, and kindness. I just wish there were something I could do for you?”

“Just make sure you hold on to that girl of yours,” he said. “Love is about all we have in this place. Never let her go.”

“I won’t,” promised Isaac. “I just hope it won’t be too long till I see her again.”

“Well, I think we only have another six months in this place before the Russians come,” said Christof, confidently.

Christof had prophesied correctly but, on liberation day, Isaac could not find him. It was all he had been able to do to avoid the death marches most of the camp had been sent on. He had hidden himself near the rubble of the crematoria which the Nazis had blown up to bury the evidence of their crimes.

Only when he was sure there were no more patrols did he come out and, shivering, make his way to the women’s blocks.

These, too, were deserted. As Isaac traced his hands along the edges of the beds, he thought how many times he had wished he could have jumped over the fence that separated his quarters from Rasia’s and come to lay down with her.

He could hear the Soviet tanks outside and, sighing deeply, took his hat off and looked at the embroidered marigold he kept underneath for safe keeping.

“Is that for me?”

Isaac turned around, slowly – hardly daring to believe his ears, or his eyes.

Her hair had grown, and she was a little thinner, but she was alive!

He pressed his lips to hers and they held each other tightly.

“It’s beautiful,” she said. “I’ll wear it on my wedding dress.”

Isaac’s world came crashing down for a moment.

“You’re…you’re engaged?”

“Yes . . . well, that is, assuming you were going to ask me?”

Isaac dropped to his knee, in prayer as much as proposal.

“You know the answer’s yes,” said Rasia. “Although, I think your needlework could do with a little practice.”

About the Creator

Tristan Stone

Tristan read Theology at Cambridge university before training to be a teacher. He has published plays, poetry and prose (non-fiction and fiction) and is working on the fourth volume of his YA "Time's Fickle Glass" series.

Enjoyed the story? Support the Creator.

Subscribe for free to receive all their stories in your feed. You could also pledge your support or give them a one-off tip, letting them know you appreciate their work.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.