The Destroyer

Short Story Entry for SFS 5: Raging Bull

I

*

The flatbed sputtered its way through the hall of coconut trees. Its cannibalised tyres stamped an irregular notation in the dust, adding a tinge of ochre to the lime-coloured fronds.

Though the wheel rattled and the bonnet’s acrid breath stung his eyes, Vadish Bhattathiri was jubilant. As joyous as Aruna — divine charioteer of the sun — returning home triumphant and heavy laden with the spoils of war. For the twentieth time since he had left Kochi, Vadish craned his head back to ensure his treasures remained safely stowed. There they were, all forty cannisters of them. Celestial weapons. Arrows to loose at the demons that plagued his village of Thiruvaka. Those caterpillars, hairy and accursed as the brows of Ravana, who fed exclusively on the roots of cardamom plants. He would vanquish them all with these American pesticides. America had harnessed the potency of the atom and sent the Japanese scuttling back across the border. That had been thirteen years ago, when Vadish was a schoolboy. Who knew what mysteries they had unravelled since? A nation that could hurl an atom bomb surely understood the best way to eradicate caterpillars of every description.

The trees fell away to reveal the steaming vistas of Wayanad. Endless rice paddies flecked with turbaned shades treading water wheels. Terraced hills rising like overgrown ziggurats. An elephant lumbered along the roadside, cords of teak wood clasped in its trunk. Its mahout barked something at Vadish, but he did not hear. The radio was blaring a tinny cacophony, each turn of the dial provoking a more bestial squawk.

“…Assured our beloved state of Kerala will not survive infancy under Namboodiripad and his Maoist bandits…”

“…Catholics have come out in droves to support the liberation…”

“…Presidential Order is wholly illegitimate. These grande bourgeois parasites are aping the British…”

The needle hit 14.5 and the vituperations crystallised into the warbling voice of a songstress. Vadish’s heart leapt. It was the same duet from the talkie the travelling projectionist had screened last week in Thiruvaka. He had taken Ujhala to see it. He had held her hand gently as the flickering lovers swooned along the sheet hung across the courtyard. She had not protested. High-born Ujhala. His beloved and perhaps, upon his victorious return, his betrothed. Vadish sung with full-throated passion.

“My heart boils over, precious one.

My heart compels my tongue to speak foolish things.

Do not mistake …”

The children materialised out of the shimmering road ahead like forest jinn. Vadish swerved with such force that the wheel broke off in his hands. Time broke also. All the screeching, blearing cosmos flowed sluggishly through his benumbed senses. Then a pall of darkness spread across the windscreen, and the terrible swiftness of the world reasserted itself in a hail of shattered glass.

**

A long, viscous moan contended with the dying gurgle of the engine.

It roused Vadish from his stupor, evaporating the luminous tadpoles that squirmed through his vision. Gradually, he hauled his aching body out of the vehicle and, through the billowing exhaust, he saw.

The flatbed had collided with a white Ongole bull, pinning it’s quaking bulk to a fig tree. Blood and fat gushed from the beast’s lacerated hump. Its hooves gouged at the leaf strewn dirt in a futile attempt to run. A caparison, festooned with sequins and bells, half covered one bulging eye.

“It wasn’t my fault! Abhi left the gate open!”

The voice sent an icy shard of horror sliding into Vadish’s guts.

The children.

He wheeled about, rushing upon the two young boys standing in the roadway. Warm relief spread through his veins when he saw they were unhurt. The relief intensified when he realised they were the sons of Eeshwar the planter, his employer.

“Abhi! Gadin! What are you doing here? I could have killed you!”

His shouts broke the dam of tears that welled behind their almond eyes. As the pair bawled, he picked them up under his arms and carried them to the shaded safety of the roadside.

II

*

“Pull!”

The men grunted and strained at the rope. Gradually, the flatbed was pulled clear of the snarl of roots and entrails. Vadish guided laxly with his hands, trying to conceal his embarrassment from the onlookers. Half of Thiruvaka had come to witness the scene. Mothers swathed in floral sarees muttered to one another, gesturing with open palms towards the dead bull. Boys from the secondary school gawked and snickered through budding moustaches.

“Are you injured?” Eeshwar enquired, placing a hand on Vadish’s shoulder.

“Only my pride is, sir. I hoped to make a grand entrance. Look.”

He retrieved a cannister.

“I have a cousin in Kochi who works on the docks. These fell off a pallet. He says there’s enough here to protect our best crops at least until the monsoon season.”

Eeshwar eyed the cannister distractedly, rubbing the folds on the back of his neck.

“I am grateful... This accident was…My sons were…”

“Don’t be troubled, sir.” Vadish cut in, his head oscillating earnestly with every word. “I myself was wayward at that age. But, as the sages say, ‘Be quick to forgive a child his mischief. Lord Krishna, the Sinless One, was mischievous in his youth. He alone can turn grain husks into precious gems.”

The clout landed on the back of Vadish’s head. Though the pain of the blow was slight, the guffawing of the schoolboys stung sharply.

“Killer! The words of the sages are ashes on your tongue!”

Vadish immediately recognised the voice of his assailant. Pulikkottil, the ancient Nambudiri priest, stood before him, brandishing his bamboo cane like a cudgel. Though he was a macerated little man, with skin like dead wood and a sickly belly that drooped over his lungi, Pulikkottil quivered with a vitalising fury. His rage had astonished the novice priests who had accompanied him down to the roadside, pleading with him in vain not to leave the safety of the temple compound and break his seasonal vows.

“Did this bull belong to you, swami? I will soon be in a position to compensate you in full.”

Vadish bent to touch Pulikkottil’s feet, receiving a second blow for his efforts.

“It was all an accident, swami,” said Eeshwar. “My sons were playing in the paddock and forgot their duties. They thought they could bring the bull back before anyone noticed. In their haste, they blundered onto the road and Vadish had to swerve.”

“It would have been better if he had struck them instead!” Pulikkottil pummelled the dust with his cane as if to officiate the pronouncement. “A useless father begets useless brats!”

“Your words go too far.” Vadish said, wincing. “I am sorry for the loss of the animal, but it can be replaced. What’s more, your herds are likely to swell very soon. I foresee a bountiful harvest.”

“Animal?”

Pulikkottil tottered over to the dead bull, his anger melting into a deluge of tears.

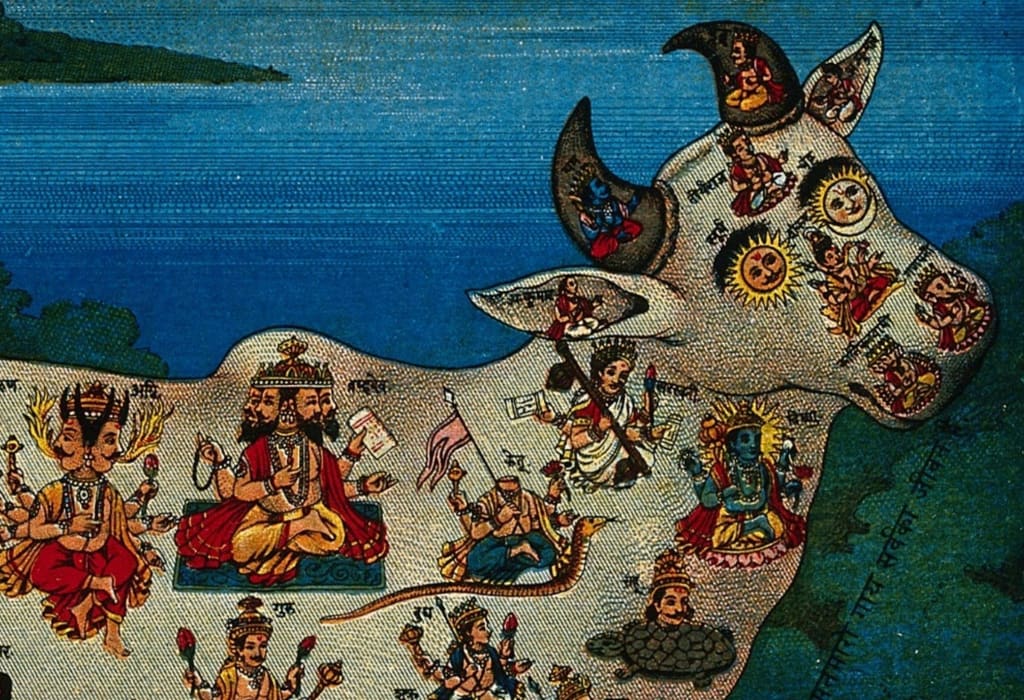

“The Mount of Shiva is no mere animal. This bull you have so carelessly slaughtered harboured the soul of Nandi. Yes, he was Nandi reborn! I discerned it in a vision.”

The crowd began to sibilate. There were gasps, stifled curses. Pulikkottil knelt beside the body and clasped his hands before his painted forehead, supplicating the discarnate guardian deity for forgiveness. After some time, he stood to address the people of Thiruvaka.

“Did I not warn that a calamity such as this would befall our village one day? Who can doubt we live in an age of vice and discord? The youth neglect the Vedas and embrace idleness and folly. Foreign fashions are prised and dharma is cast away like a rotten gourd. And now, behold, a breathless bull of metal and diesel has slain the living bull of Shiva. Woe unto us, for we have lost the favour of the Lord of All Beings! Woe unto us, for we stand defenceless and accursed!”

III

*

The train of khaki jeeps snaked through the coconut trees, red flags fluttering in the stifling heat. The mounted loudspeakers howled a watery rendition of the L'Internationale as the vernal parrots jeered from the canopy.

For the twentieth time since they had left Kochi, Vadish craned his head back to ensure the arsenal remained safely stowed. Chinese-made Kalashnikovs, all polished wood and cool steel. The righteous weaponry of the masses, destined by the inexorable dialectic to establish the worker’s paradise. To eradicate the class-enemies, the hoarders, the bloodsuckers.

“You mean to tell me you were forced into exile over a cow?”

Commissar Pranal began to chuckle, his glasses fogging with condensation.

“It was a bull, to be precise. A sacred bull,” said Vadish, grimly. “Thiruvaka has always been awash with superstition. That is why our Nambudiri brahmins have always lived like sultans. By reading portents and mumbling prophecies they keep our proletariat enthralled.”

Pranal shook his head, “If what you say is true, our task will at first be most difficult. A pious people are slow to recognise their enslavement. But, once the scales fall, it’s all downhill. They quickly exchange false consciousness for revolutionary zeal. Cinema, comrade Vadish, shall be our principal weapon.”

Pranal held up a can of film labelled:

LIES OF THE PRIESTLY CASTE: PLUCKING THE FLOWERS FROM THE CHAIN

Memories sprung at Vadish like venomous cobras.

He remembered the talkie. The swooning lovers. Ujhala’s silken palm.

He remembered the night he had stumbled to her hut, weary and frantic after a day of scorn, the scent of burning pesticide charging the air. He had been pelted with garbage and cries of ‘God killer’. His parents had greeted him with agonised smiles and begged him to find lodgings elsewhere. Ujhala had been his last hope, and when he had tapped upon her window, her face had been a rictus of fear and disgust.

In that moment he had hated her. It was a hatred that had sent him hurtling like a seething comet back to Kochi, where he had spent three years toiling as a coolie for his cousin. That was before he had become enlightened. Marx, Mao and Namboodiripad had shaped his molten anger into a steely resolve. He would enlighten Thiruvaka also. He would overturn the brahmins and shatter their beast-headed idols.

And yet, the closer he drew to the village, the more his mind shed thoughts of ideological purity, collectivisation and the brotherhood of man. He could think only of her.

**

Rejoicing farmers scythed monochrome fields of grain from the sheet that hung across the courtyard. Commissar Pranal added a cheery narration through a crackling loudspeaker.

“The farmers are happy here. The farmers are free here. They know that prosperity comes not from Vedas or carved fetishes or pujas. It comes from them alone and their righteous labouring.”

Vadish scoured the flickering, ashen faces in the audience. He walked briskly, keeping beyond the rim of the projector’s conoid glow.

She must be here. She must.

Movement caught his eye. The hem of a saree fluttered just beyond the columnar entrance to the courtyard. He recognised the diamond patterns that flashed in the milky light.

Ujhala.

Vadish pursued, his duties forgotten. He followed through the straw-littered streets where speckled fowls pecked and ruffled. He followed her through the paddock that had once belonged to Pulikkottil.

“Ujhala! Wait! Don’t you remember me?”

She disappeared behind a roadside fig tree. Grinning boyishly, Vadish crept up to it and sprung around the trunk. He expected a playful yelp. An embrace. The touch of silken skin.

His face collided with something rotten, reeking, flyblown.

Legs.

Scrambling backwards, Vadish saw the two boys that swung from the low bough. The placards hung around each broken neck read:

I STOLE CARDAMOM FROM THE PEOPLE’S GRANARY

Though the birds had taken their eyes and their tongues bulged, Vadish knew well who they were. He wept for Abhi and Gadin as the Ongole cattle watched, beholding him with black and glassy indifference.

About the Creator

Samuel David Medley

Short story writer.

Enjoyed the story? Support the Creator.

Subscribe for free to receive all their stories in your feed. You could also pledge your support or give them a one-off tip, letting them know you appreciate their work.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.