The marigold flower quivered, then stilled as it was enveloped by the resin. Rachel slid the mould under the UV lamp and set the timer for four minutes. She sat there as the tears she had been holding back welled up in her eyes. It was supposedly healthy to let yourself feel your emotions, but allowing herself to cry didn’t seem to help at all. The ugly truth was that no matter how many times she sobbed into her pillow or cried herself to sleep, her little boy was never coming back.

Toby had been six years old. That day, forever etched in her memory, had started ordinarily enough. That morning he had come inside with a tiny marigold bloom grasped between his small fingers. He had given it to her, beaming, “because it’s beautiful like you, Mummy.” She’d been sorting out paperwork and bills, so she’d smiled at him and asked him to put it somewhere safe for her, before turning back to what she was doing. How she wished she’d stopped and hugged her son, exclaimed over the flower and let him know how special it was. She hadn’t known it was the last time he would ever give her something.

She’d taken him to a playground in the afternoon. He’d chatted happily as she drove and she’d listened with half an ear, making vague encouraging noises while her mind was pre-occupied with work issues. The playground had been busy on that sunny afternoon, and they’d had to park on the other side of the road. Every time now that she replayed it in her head, she’d shout at her past self not to park there, to turn around and go home. But inevitably she and Toby had gotten out of the car and crossed the road to the playground.

She’d cheered Toby as he played on the swing, showing her how high he could swing all by himself. At least she’d done that. She’d also taken the time to sit in the sandpit with him and build a dam across the small creek created by the water fountain. She hadn’t been completely neglectful, she told herself now. But the rest of the time she had sat gratefully on a bench, watching Toby play by himself, trying not to think about work and associated stresses, or about Dan and the strain in their marriage that she could no longer ignore.

Eventually Toby had gotten tired and hungry, and it was time to go home. She’d picked up his discarded jacket, and they’d walked over to the road. They’d been standing on the footpath, Toby’s hand in hers, when it happened.

She remembered how she had stood there with Toby’s small hand seemingly secure in her grasp. The next thing she could remember was a loud crash that seemed to reverberate through her skull, the hideous sound of metal twisting and deforming, and Toby’s hand being pulled from hers. Then she was on the road, and she remembered her desperation as she tried to lift her head and find Toby; her panic in the moments before she lost consciousness.

Witnesses at the scene later described how the car had hurtled down the road, out of control, before ricocheting off a parked car and onto the footpath where Rachel and Toby were standing. The driver fled the scene but was soon found by police, stumbling, and slurring his words. Testing had confirmed that he was intoxicated.

She remembered waking up in the emergency department. Her emergency department, where she faithfully worked her shifts as an emergency nurse; doing the overtime when others couldn’t and giving everything to the job she at times both loved and hated. Around her had been familiar faces, concern in their eyes. She had wanted to know only one thing - where was Toby? She’d spoken his name from between swollen and bruised lips, with no response except hesitant looks. She’d repeated his name, her voice growing shrill as panic gripped her heart. She had seen that pause, where words had to be carefully considered and chosen, often enough to know what it meant. But she couldn’t believe it; surely God wouldn’t spare her and not Toby?

It was Christine, a fellow nurse, who had placed a hand on Rachel’s shoulder and uttered the words that she had heard so often in this place, words spoken to family members who looked at them with tear-stained eyes tinged equally with hope and fear, “I’m sorry”. Her denials had slipped away then, taking with them hope and joy. Toby was dead. Her boy, who bounced out of bed each morning, who loved to draw animal pictures and make up stories, who clung to her at night when she tucked him into bed and made her promise that she would always be his Mummy - dead. Rachel had stared up the ceiling with dry eyes. Not speaking, not moving, not thinking. Just numb.

“I’ve called Dan, he’s on his way.” It had been Christine again. She’d sounded like she had been crying. Rachel had distantly wondered why; after all Toby wasn’t her son. And Dan – what good would he be? They could barely communicate with each other in normal everyday life, let alone in a crisis. It seemed hardly likely they could be of any comfort or help to each other.

It was a week before she left hospital. She had escaped serious, disabling injury, but needed surgery to fix a fractured jawbone; and she had near-constant headaches from the blow that had knocked her unconscious. She’d asked incessantly about Toby’s death whilst in hospital, needing to know despite the pain of the details. She’d learned that he had been crushed between the drunk driver’s car and a parked car, resulting in injuries so severe he had died on the way to hospital. And now she was supposed to be planning his funeral, but her mind stubbornly refused to move on, circling uselessly around and around the fact that her son was dead.

Nothing would have happened over that time if it weren’t for her mother, who - despite her own grief - was a steadfast, calm, and practical presence. It was her mother who had taken her to the funeral home where she finally saw Toby, lying in a coffin too small to be fair, his clothing covering the terrible injuries that had ended his life. His face seemed far too pale and still to belong to her talkative and bright boy, who was always bursting with curiosity about the world and asking endless questions. But it was him, and now it was real.

In due course, the funeral occurred, Toby was buried, and Rachel returned to a home that would never be right again. Her work had given her as much time off as she needed, which left her drifting aimlessly around a house devoid of anything she cared about. Dan buried himself in his work and she barely saw him. She vaguely recognised it as his way of coping but couldn’t bring herself to care.

One morning, when she was staring out the kitchen window at nothing at all, she suddenly saw the marigold. Toby had left the tiny flower on the windowsill, and the sunlight had dried and preserved it. Rachel picked it up and gently held it, studying it. Then she had walked into the study and picked up her resin kit.

After the resin set, she sanded and polished the flower’s tiny transparent receptacle until it gleamed. That done, she threaded it onto a fine chain and clasped it around her neck. This was Toby’s last gift to her, and she would wear it always.

Time passed. Her headaches settled and her face healed. She and Dan barely spoke to one other, and eventually decided there was no point in staying married. She went back to work, partly because she didn’t know what else to do with herself, but the pediatric trauma cases stirred up the grief she wanted to keep hidden. She changed jobs, going to a hospital without a pediatric service. She told no-one there about Toby; she didn’t want their uncomfortable pity.

Since Toby’s funeral, a thought-turned-intent had slowly coalesced in Rachel’s mind. She knew the driver had been arrested at the scene. He was charged with driving under the influence and manslaughter. Rachel hadn’t trusted herself to attend the hearings, but the newspapers reported a guilty plea and a prison sentence of seven years. It would never be enough for Toby’s life, and Rachel had decided that she would take matters into her own hands at the first opportunity.

She got her chance sooner than expected. The hospital she worked at was close to where Toby’s killer was imprisoned. Inmates from there would be transported to the hospital when they needed medical attention beyond the skills or resources of the prison staff. Half-way through her shift one day, the coordinator let her know they were bringing a prisoner under guard into one of her cubicles. “Hanged himself,” he remarked offhandedly, “but didn’t do a very good job of it. Just needs a review.” He walked away, and Rachel checked the cubicle, making sure the bed was prepared and all the monitoring in place. Then she went over to the computer with the patient list.

Time stopped as she read the name of her new patient. It was him. The one who had taken her child from her.

One of the front nurses led him in. He was of average height, balding, skinny, and stooped. She thought they made an odd-looking train; the nurse with her efficient step and business-like manner, the prisoner with manacled wrists and lowered head, and finally the bored looking police officer. There appeared nothing malevolent about the prisoner, and in any other situation she would not have looked twice at him.

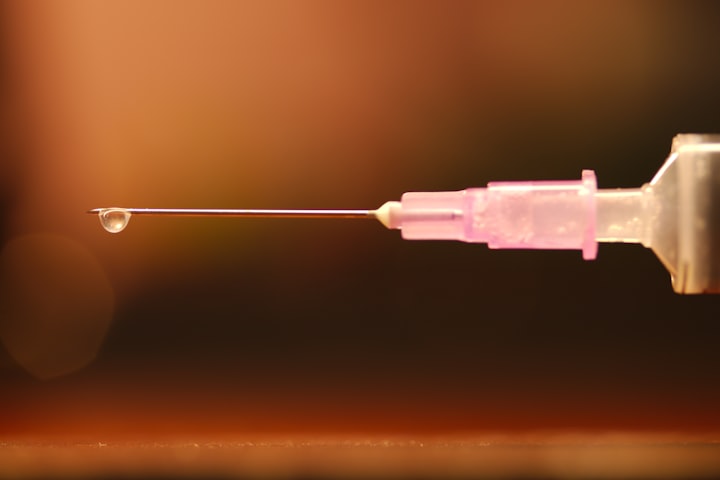

She’d prepared a tray of standard blood-taking equipment, with one addition. Whilst waiting, she had slipped into the medication room and filled a syringe with potassium chloride. Now the innocuous looking syringe sat on her tray with an empty saline tube next to it, giving the appearance of the standard solution for flushing an intravenous line. Except this injection would stop the heart of Toby’s killer. It was the same drug used to execute criminals on death row, which Rachel thought entirely fitting.

With the patient settled in, Rachel collected her tray and went into the cubicle. Without any hint of her true feelings, she welcomed him and let him know that she was going to set up his monitoring and take some blood tests. He didn’t look up at all, just mumbled his assent. Rachel attached the monitoring leads, and then tied a tourniquet around his arm. Years of practice enabled her to swiftly insert an intravenous line, take blood, and attach the bung. Then she picked up the potassium chloride injection, her heart beating so fast and so loud she was sure he must be able to hear it.

As she bent over his arm, deadly syringe in hand, the marigold pendant slipped forward and swung into her vision. She froze, her eyes fixed on it as it trembled and twisted at the end of the chain. She heard Toby’s voice as if he were standing next to her, “It’s beautiful like you, Mummy”. Toby, her beloved boy, who knew that his mummy was perfect and good and kind. The syringe slipped from her nerveless fingers, and she found herself looking into the eyes of the man she had been about to kill, eyes that were drowned in more despair that she could possibly have imagined.

Rachel turned and walked away, throwing the syringe in a bin as she went. She would tell her coordinator she had a headache, she decided. Then she would go and get some flowers to put on Toby’s grave. She hoped she could find some marigolds.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.